The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

First order of business: I had the pleasure to discuss inflation on Vox’s “The Weeds” podcast earlier this week. You can listen to it here or wherever you get your podcasts!

Today’s post is a guest post! Maia Mindel is an Argentine economics consultant and writer with a focus on monetary policy, macroeconomics, and data analysis. You can follow her on Twitter @MonetaristMaia or read her amazing blog, “Some Unpleasant Arithmetic”, linked below:

“2001” is remembered by most living Argentines as the worst year, economy-wise, of their lifetimes, even beating out the 1989 hyperinflation. Unemployment and poverty soared while the economy sank, with a four-year slump bottoming out in that year after draconian restrictions on cash withdrawals from bank accounts. The government, instead of the traditional Keynesian solutions to downturns, tightened its belt with widespread budget cuts and ever-higher interest rates. Why did it happen? And why did nobody implement different policies that would ameliorate the crisis?

El infierno tan temido

The story of how everything got so bad goes back to the 1989 hyperinflation, ironically enough. Because of longstanding issues with fiscal, monetary, trade, and labor policy, Argentina’s economy spent most of the 1970s and all of the 80s with triple-digit inflation (the lowest levels were 50% annual in 1985, and then 140% in the late 70s) and with real GDP per capita actually decreasing in that period. Because the perceived costs of stabilization were so high, the first democratically elected President in a decade, Ricardo Alfonsín, postponed stabilization until the situation was unsustainable, and in 1989 their flimsy heterodox schemes to reduce price growth through price and wage agreements and fiscal restraint failed completely—primarily because of extremely loose monetary policy.

Regardless, by 1989 the situation had reached a point of no return, with prices off in an unstoppable race and expectations barely remaining steady week-by-week. My father remembers going to the store Monday because products would get more expensive by Wednesday or Thursday. 1989 was a terrible year, with ever-growing price growth leading to large cuts in real incomes (both wages and profits), lower aggregate demand, and all around misery. Poverty and inequality soared since those hardest hit were the lowest earners, due to their relative inability to protect their earnings by converting them into US dollars.

The dollar is probably the main character of both the 1980s and the 1990s. Because of extremely high inflation, particularly after the 1980s, Argentines shielded their assets by turning to the US dollar as a safe store of value (and also to real estate, but that’s neither here nor there). As inflation went higher and higher, the degree of monetization of the economy was reduced further and further, and the share of transactions and contracts conducted in US dollars was higher and higher. Consequently, the US dollar had a huge role to play as a shorthand of inflation rates during high uncertainty, resulting in it becoming the nominal anchor of the economy. This dynamic was common to many, if not all, Latin American countries, all of which had “lost decades” of their own with differing degrees of inflation.

Frequently, particularly in the 1970s, central banks attempted to use the exchange rate’s power over inflation to their benefit. Since people pinned their inflation expectations on the USD, the central banks could peg the exchange rate, and thus disinflate the economy (accompanied by other policies of various natures). Normally, the peg would be sustained by capital inflows from American banks, as monetary policy was loose and real interest rates were low. These plans were somewhat successful until 1979, when Paul Volcker hiked interest rates upwards to curb inflation, and capital flight ensued. The secondary issue of pegged exchange rates was that, while nominal rates (i.e. the “plain” figure, say 200 pesos to a dollar) remained constant, real rates lurked upwards—making exports less and less competitive while imports became equally cheaper. Both of these imbalances resulted in pegged rates being unworkable as tools of stabilization for the following decades.

Putting the dollar into idolatry

Going back to 1989, the situation was getting increasingly worse, as annual inflation rose to levels in the thousands, which led to mass strikes, a deeper recession, and even military uprisings against the government. The incoming President, Carlos Saúl Menem, came from Argentina’s traditionally populist Peronist Party and had promised mass wage increases and a “productive revolution”, campaigning in alliance with labor unions and industrialists. Instead, after a few failed attempts at taming inflation, his solution to inflation was extremely different to the party’s traditional measures (price controls, export bans, etc), and so were the rest of his policies.

How did Menem end hyperinflation? The 1991 Convertibility Plan was his solution. Convertibility had three main planks. The first one was fiscal restraint, with a drastically reduced public sector, accomplished by reforming taxes, privatizing social security, reducing public employment, and privatizing state-owned companies. Tied to this were the massive reforms in trade, labor, and financial policy, which moved the country in a boldly pro-market stance—a far cry from the nationalist statism of the 1940s. Secondly, the Central Bank was made independent, and the link between the deficit and monetary emission was broken by legally banning the Bank from lending any money to the government, and most of the heavily subsidized loans to private companies were eliminated. Thirdly, the currency was changed from the Austral back to the traditional Peso, and a currency board was instituted.

A currency board is, bluntly, a souped-up peg. Under this regime, the Central Bank is committed to back all of its monetary liabilities (i.e. “cash”) with international reserves, and so to exchange pesos for dollars at an agreed upon, fixed rate. In this case, Argentina used a now legendary parity: “one for one” (uno a uno), 1 peso for 1 dollar. This massively restricts the powers of monetary policy, since the supply of money is endogenous to the reserves the Central Bank has, which are determined by the trade balance and capital inflows. The US dollar was made, for all intents and purposes, legal tender in Argentina. Tied to this, capital mobility was ensured to be entirely free. Lastly, the Central Bank had to properly regulate private banks, since it could not really act as a lender of last resort.

Why were such draconian, restrictive measures implemented? As I’ve written before, inflation, and particularly hyperinflation, are almost entirely expectations-driven. Particularly, expectations of whether or not a given policy regime is sustainable and credible are key: a currency peg might not even stabilize inflation because reserves are known to be insufficient to maintain it, triggering a balance of payments crisis sooner than later. In consequence, to avoid falling into the “half measures” trap, the Menem administration moved towards a policy regime that tied their hands in certain highly recognizable ways; by ending permanently seigniorage, rather than just forgo it temporarily, he made his goal to fund the deficit purely through the debt market believable.

Fiscal balance was the key to the Convertibility: large reforms allowed the primary deficit to go down from 10% of GDP in 1989, almost all of it funded through money injections, to basically 0 by the early 90s. The biggest reforms were the privatization of state owned companies, which accounted for roughly 40% of the deficit, and the privatization of Social Security, which was left unfunded for present and soon-to-be retirees. Taxes that provided large chunks of government revenue, like export taxes (equivalent to a third of all resources) were scrapped, and replaced by an improved VAT and income tax system.

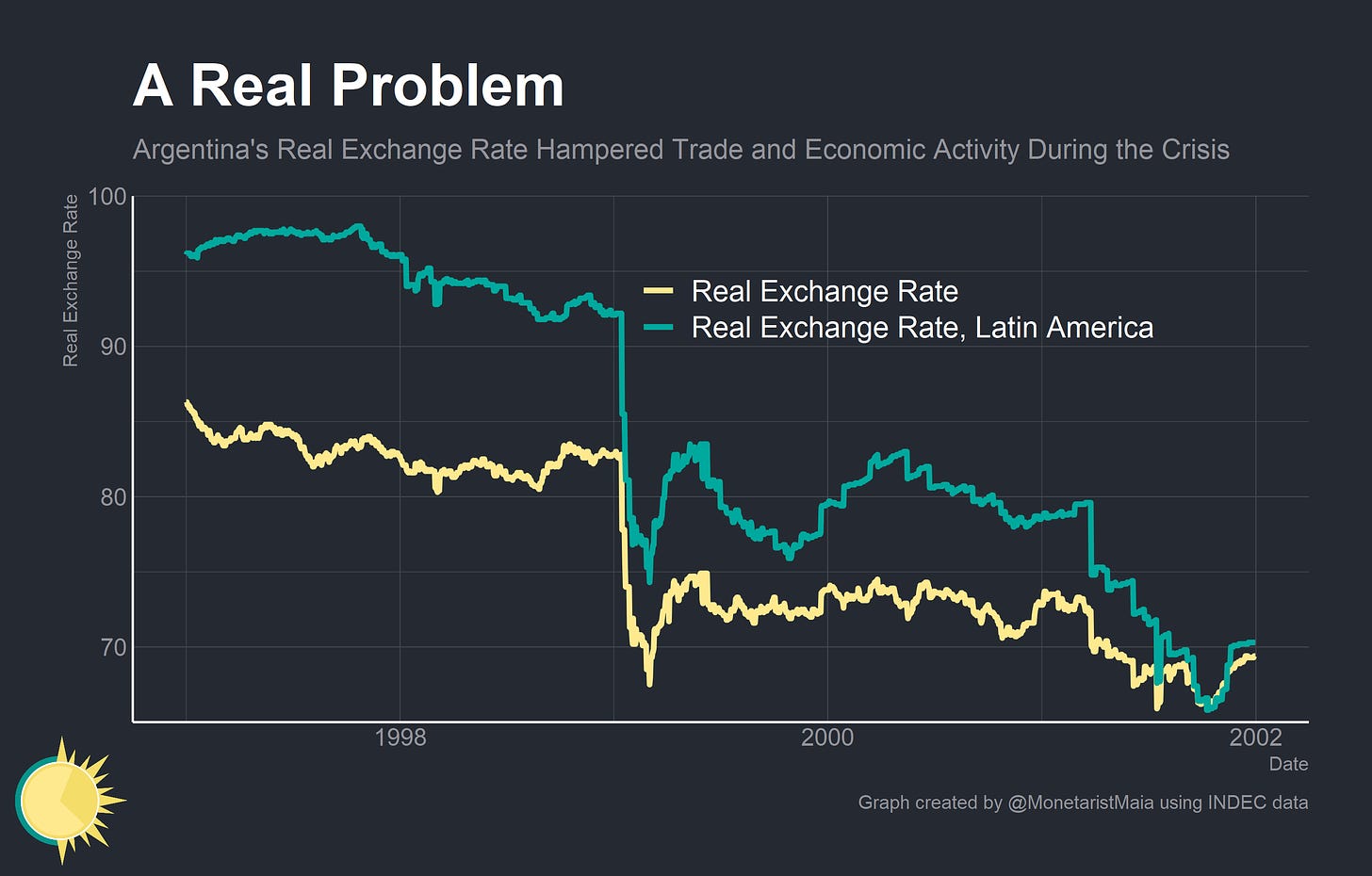

The Gordian Knot

By 1995, the program was widely understood to be a success. Convertibility was incredibly successful at stabilizing the economy, with the inflation rate plummeting out of hyperinflation territory almost immediately, and dropping from 171% in 1991 to 10% in 1993 and then to 4.7% in 1994. This success resulted in increased money demand, which quadrupled from 5% to nearly 20% in the aforementioned period. Credit also grew, doubling as a share of GDP. However, a sticking point of this success was that a large percentage of all deposits and loans was denominated in US dollars. Additionally, the current account started worsening soon, even if exports were growing rapidly, due to an overvalued exchange rate: the rapid disinflation still included a significant degree of inflation, which made the exchange rate increasingly less and less competitive.

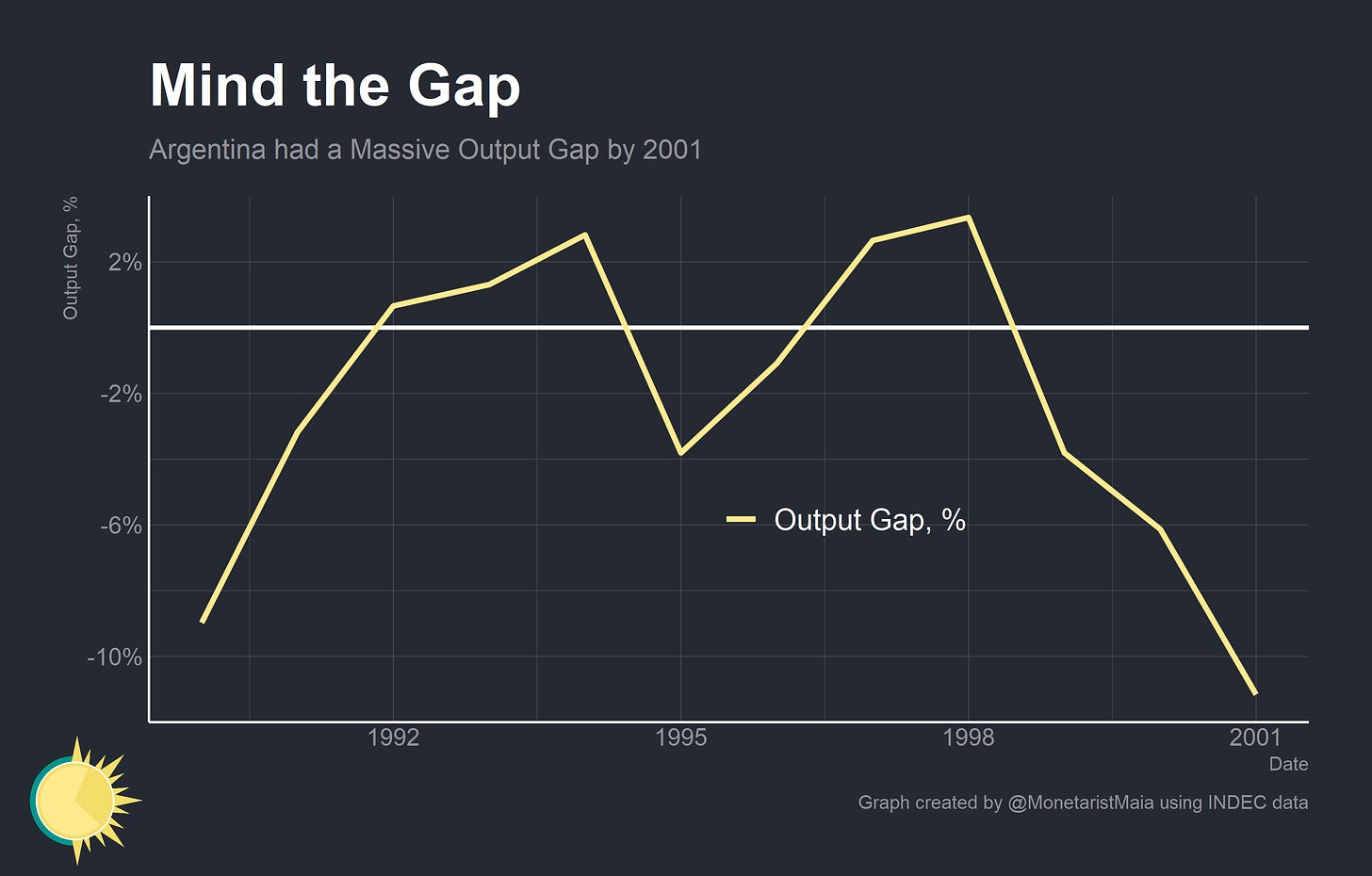

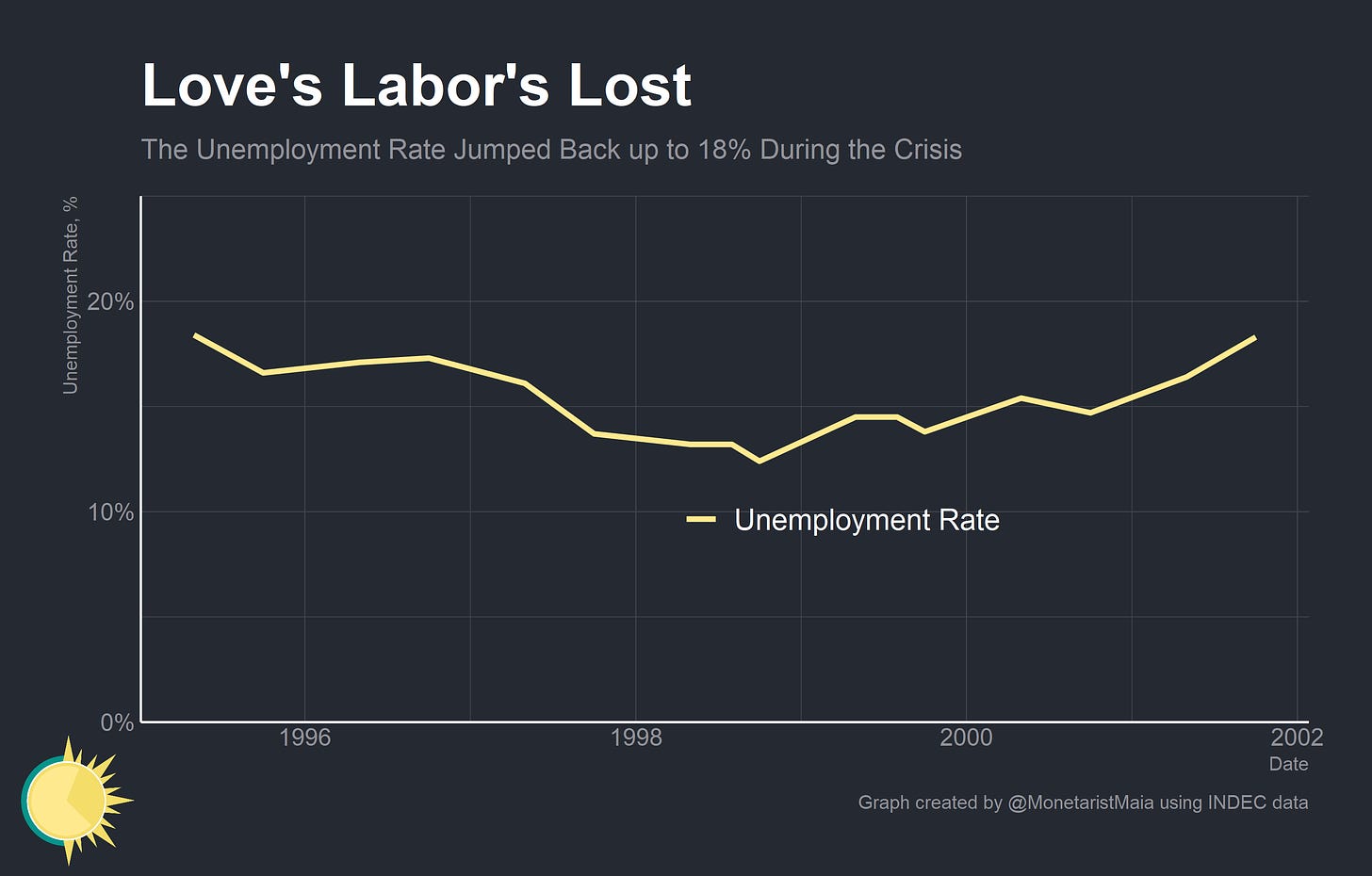

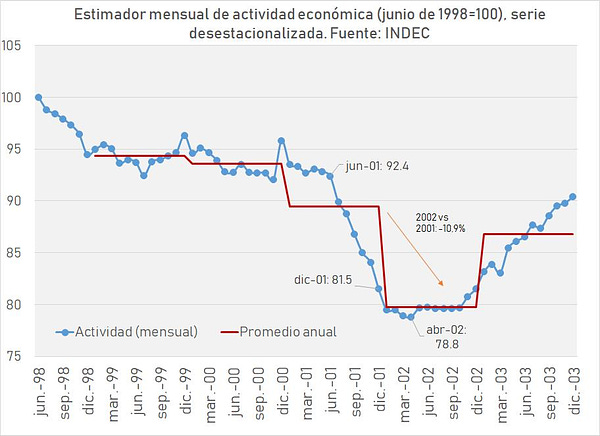

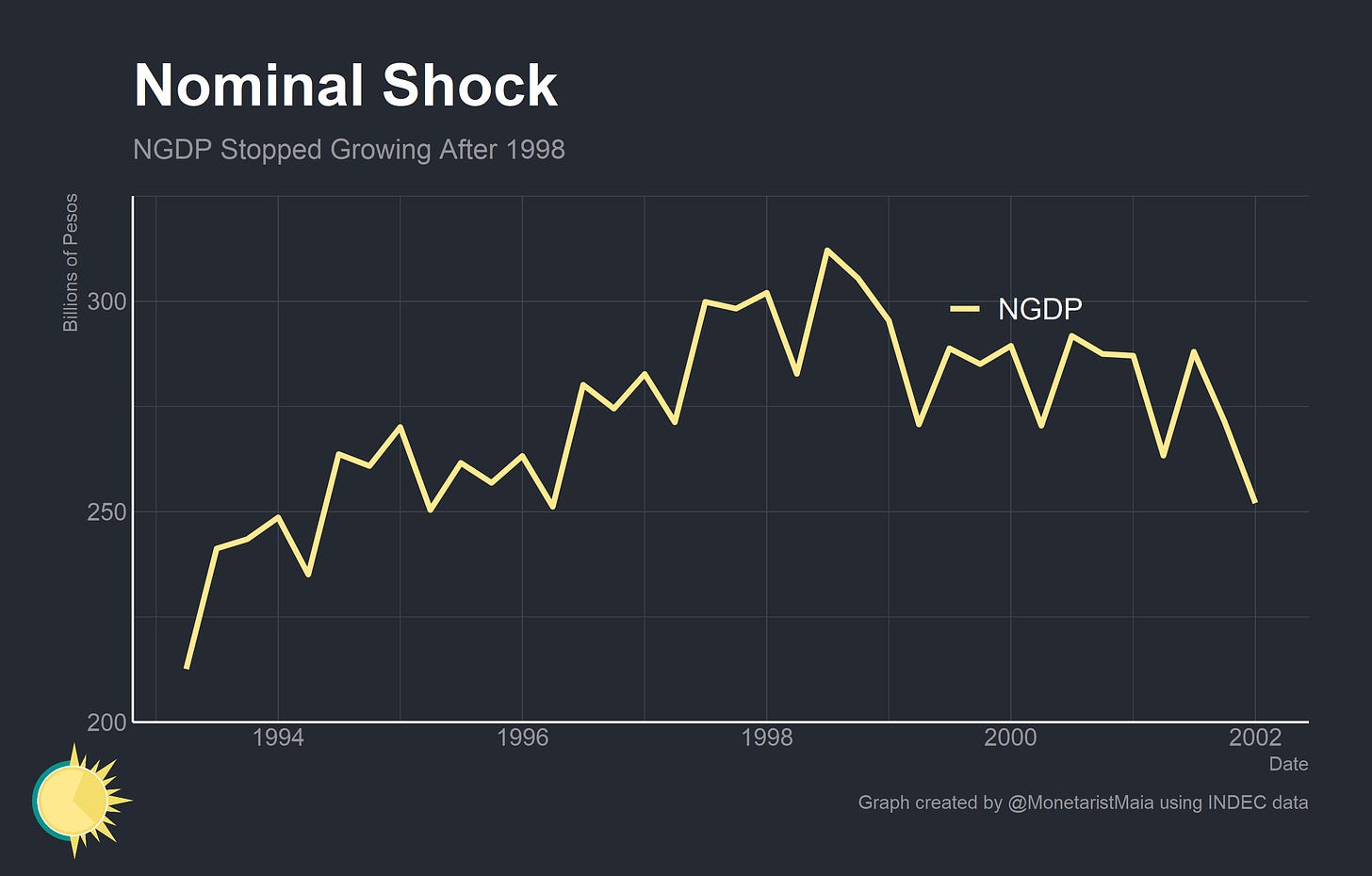

Then, tragedy struck: a series of countries began having currency and/or financial crises, starting with the “Tequila Effect” of the Mexican peso crisis in 1994, followed by the “Asian tigers” in 1997, Russia in 1998, and Brazil in 1999. Between 1997 and 2001, the economic situation grew worse and worse. Unemployment grew from the mid 10s to the 20s, poverty started covering a majority and then some of the population, and economic activity declined - from the Q2-98 peak to the first quarter of 2001, nominal GDP dropped 16% and the output gap soared to double-digit levels. The economy became mired in increasingly severe deflation, and the price level fell for 25 months straight. By late 2001, the situation became so dire that the President, Fernando De La Rúa, resigned amid mass protests, triggering an institutional crisis that went through four other Presidents in two weeks, ending with the office being held by Eduardo Duhalde, loser of the 1999 election.

The labor market was already weak due to the country taking so long to readjust after the structural shock that was the rapid liberalization of the economy and an 800,000 head cut to public employment, with large numbers of workers being laid off and a widening gap between the educated and the unskilled; paired with a higher real exchange rate. This isn’t particularly relevant to the larger macroeconomic story, but the appreciating exchange rate and the fact that the country had extremely high tariff rates even by the late 80s meant that the transition could have been eased through fiscal support.

Firstly, the lack of regulations on financial flows resulted in Argentina being extremely vulnerable to a sudden stop—i.e., capital flows abandoning the country at the flip of a coin. Secondly, these crises normally ended after the government devalued the currency and relieved pressure on interest rates and on borrowing constraints. Plus, since most Latin American countries had some manner or another of a crisis in the late 90s, they all began devaluing their currency. Their role as leading trade partners to Argentina meant that the country not only had already endured a higher real exchange rate, but that its position (particularly relative to Brazil, the country’s main partner) was getting worse and worse. Lastly, the terms of trade (i.e. the amount of imports that a country’s exports can buy) began worsening, partly due to a stronger US dollar and tighter monetary policy in the sole superpower.

Fiscally, the country faced major issues. In the first place, while the federal government had signed onto its promises hook, line, and sinker, the provinces were less than thrilled, running large deficits and requiring more and more money through the tax sharing system known as coparticipation. In the second place, the badly designed pension privatization had left the government with all of the liabilities (i.e. the pensions), but privatized all the income to sustain them. For example, while the budget was balanced in 2001, the non-pension parts of the national public sector were running a 3% surplus—meaning that the authorities were spending 3% of GDP on pension liabilities. Both of these put a massive strain on the system, since all debt was legally in US dollars by design. This reading of the situation isn’t uncontroversial, since at the time it was not clear why the authorities couldn’t have simply relied even more heavily on fiscal adjustment to sort out these disequilibria (the answer, as ever, is politics).

The cure or the disease

Normally, countries faced with any of those problems would simply devalue the currency and relieve pressure on interest rates. But because Argentina had a currency board, not a peg, this wasn’t legally possible. The solution, then, had to be higher rates, with an ensuing impact on economic activity. Plus, the Treasury consistently engaged in contractionary policy throughout the 1999-2001 period, since it had to find ways to finance itself as banks fled the country’s bond market. Country risk, the difference between the interest paid by the US Treasury and any given country, soared during the late 90’s, steadily diverging from the developing world and surpassing 2000 basis points (i.e., 20% more than the T-bill) by late 2001.

To preserve Convertibility, the government made a uniquely terrible decision in late 2001 as a last ditch effort to preserve the Convertibility regime from collapse: it heavily restricted the withdrawal of cash from bank accounts, to prevent a mass currency panic that would implode the financial system—due to the Central Bank’s extremely limited capacity to intervene and bail out failing banks. This entailed an immediate collapse of economic activity in a cash-based economy, with monthly nominal GDP dropping 7% in the final quarter of 2001. In old school monetarist terms (I am, of course, one of the monetarist teens, per the Twitter handle), besides a hefty contraction of the money supply, the government also engineered a drop in the velocity of circulation—and nominal output, either through deflation or recession, had to foot the bill.

But why didn’t Argentina scrap it? Besides politics, there were two main reasons. The first is that policymakers were scared that going off the 1 to 1 system would unanchor inflation expectations, bringing the country back to, if not the high inflation 70s and 80s, at least the moderate inflation 60s. Because the exchange rate acted as a nominal anchor on expectations, exiting the convertibility system and devaluing the currency was a massive leap of faith that a decade of no inflation would have taken hold—and policy makers weren’t willing to make that leap.

Secondly, Convertibility wasn’t just a currency board—it also allowed for most contracts, and the vast majority of the financial system, to be denominated in US dollars, at the same time that an improperly regulated banking system had built up liabilities denominated in US dollars, whilst there weren’t enough Central Bank reserves to back them. Thus, not just the rupture of the system, but “only” a devaluation within it, would have had catastrophic consequences: on the financial side, a banking crisis that bankrupted either most (or all) of the country’s financial institutions, and on the real sector, widespread disorganization as all contracts were hastily rewritten. After the dust settled, any government intervention would amount to a massive transfer of resources, in favor of whoever was a debtor but against anyone who was a creditor.

Nailed to the cross of gold

Having behind us the commercial interests and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.

William Jennings Bryan, speech at the 1896 Democratic Convention

What exactly did happen? My reading, as a 100% personal opinion, is that this is most similar to the Great Depression in developed countries, particularly the US. I have actually written all about it on my substack, so be sure to check that out if you want to learn more about it.

The traditional Keynesian story of the Great Depression goes as follows: the Depression happened for whatever reason (after the 1960s, because of de facto tight monetary policy), and then the Federal Reserve slashed rates to 0%. But because it couldn’t reduce rates any further, monetary policy became ineffective at stimulating the economy - what’s known as a liquidity trap. This phenomenon, of interest rates being at a very low level but inflation remaining low, was considered a historical curiosity until the 1990s - when papers by Paul Krugman and Ben Bernanke reexamined Japan’s problems from this lens. Inflation that is “too low”, or even deflation, is a problem because it points to a shortfall in aggregate demand (or below-trend nominal output, in other terms), which is bad.

Right out the gate, Krugman’s 1995 paper “It’s Baaack” breaks with tradition because it rewrote what the problem with the liquidity trap is. Traditional models ignored that most economies are open, so the exchange rate and trade play a role; that the financial sector exists, and that expectations rule everything around us. The trade issue is not that relevant, but the financial and expectations aspects are vital. Firstly, banks can actually decide how much money they create, contrary to common explanations, like that they loan out deposits or that they are bound by a “monetary multiplier”, so in fact a central bank could be incapable of expanding broader monetary aggregates simply because banks don’t want to make more loans. But why wouldn’t they? Well, here’s where the genius of this paper comes. The liquidity trap isn’t created by people not expecting monetary policy to not be effective—it’s created by people not expecting the central bank to commit to inflating the economy.

Most of the literature on central bank credibility focuses on why promises to lower inflation might not be credible (Kydland & Prescott, Barro & Gordon): because there’s an assumed tradeoff between inflation and unemployment (which might or might not be real), and because central bankers might prefer a little bit less unemployment at the expense of a little bit more of inflation. But everyone in macroeconomics knows this, so outside of a few countries like Argentina or Turkey, central banks fight really hard for everyone to trust that they’re super tough on inflation.

The consequence, of course, is when they promise to raise inflation (and therefore stimulate the economy) nobody believes they’re serious about those commitments, leaving the economy in a state of stagnation for a long time.

So where does this literature on credibility, commitments, and monetary policy come in? Well, the United States used the gold standard as a way to shore up credibility until the Great Depression—in the words of Herbert Hoover “We have gold because we cannot trust governments”. The Convertibility’s currency board acted as a gold standard of sorts (and it was actually directly based on a currency board that did preserve a gold standard), tying the Central Bank’s hands to prevent it from repeating its mistakes during the 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s (well, the one mistake really).

And how did the gold standard’s story end in the Great Depression? The conventional wisdom that the New Deal ended the Depression is wrong. The stimulus, according to Paul Krugman, was 3% of GDP—impressive, but dwarfed by the 25% of GDP the US did last year, or by the fact that actual GDP was 42% lower than potential GDP. In fact, it barely made a dent - what truly ended the Depression was getting the US off the gold standard. It wasn’t just that it inflated the economy—the recovery began after the announcement of the measure. The reason, according to Eggertson (2008), is that the announcement changed expectations—people saw that there was a credible commitment to inflating the economy until it recovered, so they acted as though it would happen, which helped it happen.

Conclusion

We already know that the Convertibility, much like the gold standard before it, sank the economy into a multi-year recession through bad design. Since ending Convertibility was a non-starter policywise, the only solution was to maintain the system by keeping the country’s balance of payments settled - which meant attracting foreign capitals as the trade position worsened (due to the overvalued peso) and interest payments soared. To accomplish this, interest rates had to be kept above the international level, and they grew increasingly higher to compensate for the country’s staggering risk premium. Meanwhile, fiscal policy also moved in a pro-cyclical direction, by slashing the budget within an inch of its life to avoid a buildup of debt that was patently unsustainable.

Why the parallels with the Great Depression? Because, in both cases, the economy was crippled by uniquely bad monetary institutions that sought to preserve credibility, with the efforts needed to preserve them causing untold pains in terms of employment and output. Additionally, both had the same ending. After some notable political turmoil, a new President was chosen by Congress. In a recent interview, his Economy Minister, Jorge Remes Lenicov, makes the comparison between 1933 and 2002 explicit: he and his team modeled the exit from Convertibility after Roosevelt’s suspension of the gold standard during the beginning of his term. The economy, particularly investment, recovered swiftly, after a double-dip in the economy due to the aforementioned disorganization from the mass breakdown of contracts. But of course, Roosevelt didn’t end the gold standard permanently (that was Nixon in the 1970s), while Duhalde and Remes did kill Convertibility— - and shortly after, the cause of 50 years of troubles, monetary financing of the deficit, returned to the economy.

Sources

Context

Frenkel & Rapetti (2010), “A concise history of exchange rate regimes in Latin America”

Kiguel & Neumeyer (1995), “Seigniorage and Inflation: The Case of Argentina”

Convertibility

Kiguel (1995), “The Argentine Currency Board”

IMF (2004), “The IMF and Argentina, 1991- 2001”

Cetrángolo & Jimenez (2003), “Política fiscal en Argentina durante el régimen de convertibilidad” (in Spanish)

Galiani, Heymann & Tommassi, (2002) “Missed Expectations: The Argentine Convertibility”

The issues

This presentation by Ariel Burstein and Iván Werning

Fanelli, Heymann, & Ramos (2002), “Dilemas monetarios en la Argentina” (in Spanish)

Hausmann & Velasco (2002), “Hard Money's Soft Underbelly: Understanding the Argentine Crisis”

Heymann (2007), “Macroeconomics of broken promises”

Della Paolera & Taylor (2003), “Gaucho Banking Redux”

The Great Depression

Sumner (2021), “The Princeton School and the Zero Lower Bound”

Krugman (1998), “It’s Baaack: Japan’s Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap”

Bernanke (1999), “Japanese Monetary Policy: A Case of Self-Induced Paralysis?”

Eggertsson (2008), “Great Expectations and the End of the Depression”

The consequence, of course, is when they promise to raise inflation (and therefore stimulate the economy) nobody believes they’re serious about those commitments

And

is that the announcement changed expectations—people saw that there was a credible commitment to inflating the economy until it recovered

Thank you 😘 had long wondered about that!