2023 Economic Year-in-Review

10 Charts on a Historic Year for the US Economy

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 37,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

In the final days of 2022, economic forecasts were sobering: consensus projections saw a year of exceedingly weak growth amid tangible risks of a downturn. At last year’s December Federal Reserve meeting, the median member projected a recessionary increase in the unemployment rate and extremely low growth for 2023. Professional forecasters were hardly rosier, putting the chances of economic decline at some of the highest levels in years.

One year later, growth has instead massively exceeded expectations, with GDP rising 2.3% through Q3 alone and the US adding 2.8M jobs since last November. Meanwhile, inflation has cooled to some of the lowest levels since the initial price surges of 2021, with core PCE inflation already coming in below the Fed’s late-2022 projections. 2023 was a year about defying expectations—turning what was once a bleak outlook into a story of remarkable recovery.

Looking Back at 2023

This year’s growth has been especially remarkable considering it was struck early on with the largest banking panic in a decade and a half. Losses on long-maturity debt holdings caused by rising interest rates combined with flighty, concentrated bases of uninsured depositors to produce the conditions for a series of bank runs—starting with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, failures quickly spread to Signature Bank then steadily engulfed Credit Suisse and First Republic. Backstopping of uninsured depositors, alongside the creation of the Bank Term Funding Program and changes to Fed discount window lending to banks, eventually stemmed the tide of failure, but not before causing a pullback in banks’ willingness to lend.

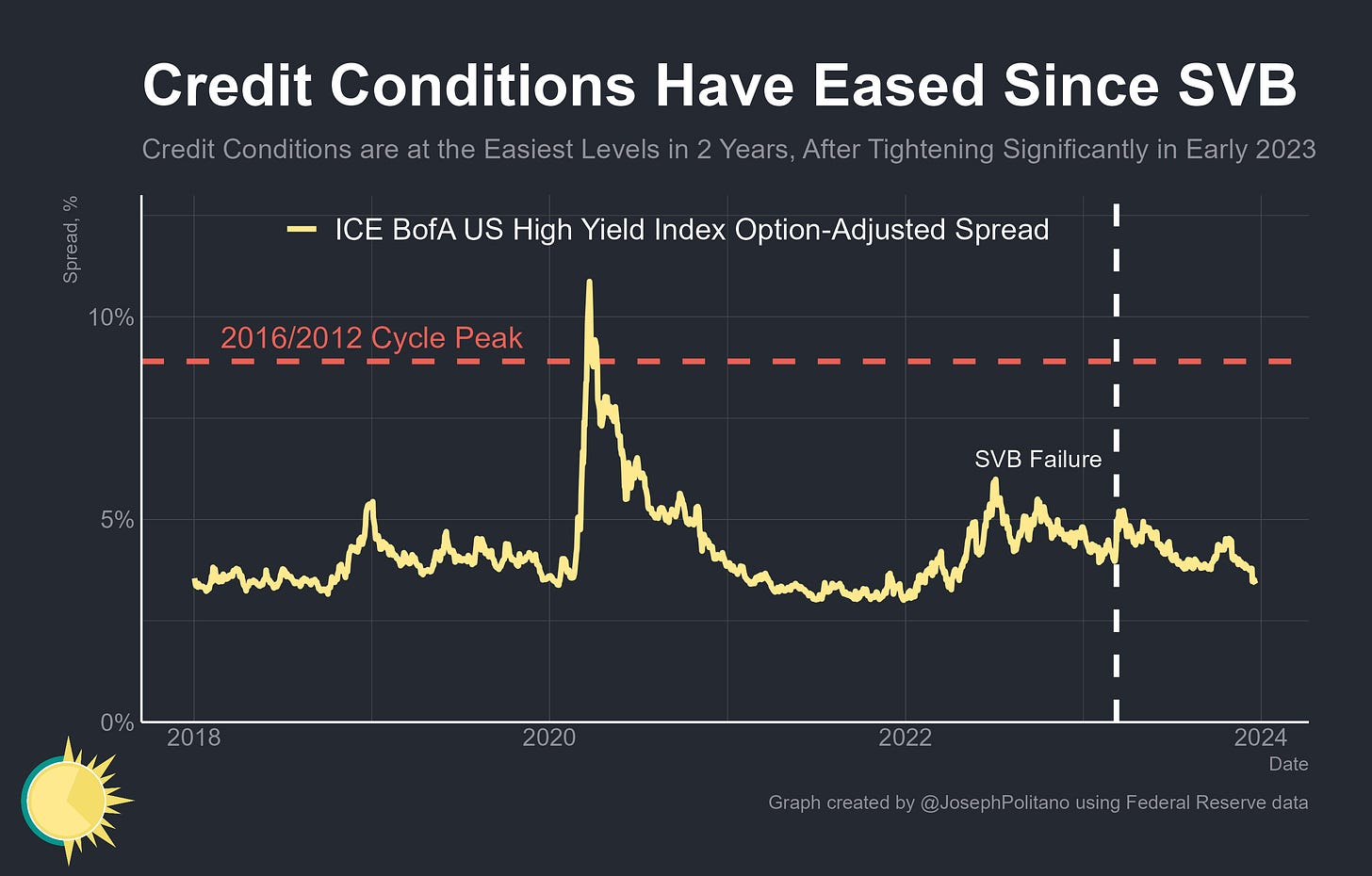

Indeed, early 2023 saw a significant temporary worsening of global credit conditions coinciding with the failure of SVB, as high-yield credit risk spiked in March. The banking crisis drove “midsized” regional banks to cut back their lending out of liquidity fears—and that was on top of the preexisting tightening of lending standards seen across nearly all banks thanks to recession fears. Yet over the remainder of this year, financial conditions steadily improved as growth remained strong and downturn risks waned, leaving them arguably at the easiest levels since the start of the Fed’s tightening cycle.

Inflation was still the central issue for central banks—but this year saw continued, substantial improvements in price pressures across multiple fronts. Energy prices dropped amidst rising American oil and gas supply, food inflation slowed as the aftereffects of Russia’s invasion faded, and housing inflation declined as the lagging effects of cooler rental markets began passing through to official data. Prices for core manufactured goods—the quintessential story of idiosyncratic pandemic-driven supply-chain inflation—even fell for the first time since early 2020.

Indeed, the slowdown of inflation was helped in no small part by the ongoing process of supply-chain renormalization that began in 2022. American manufacturers have cited materials, logistics, and labor constraints at continually declining levels throughout 2023, especially in key complex industries where supply-side problems had been most acute. For the first time in three years, semiconductors were no longer in shortage, allowing for a recovery in domestic car production and ongoing falls in used car prices.

Yet more important to the long-run decline in inflation was the cyclical slowdown to nominal demand—consumer spending is up a healthy-but-not-too-abnormal 5.4% over the last year, compared to the 6.9% growth seen at the same time in 2022. Slower hiring and wage growth have brought aggregate nominal income growth closer to normal levels, and that normalization in incomes has in turn helped cool the cyclical components of inflation. Importantly, the decline in inflation and alleviation of supply-side constraints has been so substantial that real wage growth has actually increased even as nominal wage growth slows.

The “Great Resignation”—or “Great Reshuffling”—also largely ended this year. For most of 2021 and 2022, exceptionally tight job markets made quitting for better work or higher pay more common than ever before, leading to an unprecedented reallocation of labor. This year’s cooling labor market has meant less hiring and job-hopping, bringing quit rates back in line with their pre-COVID levels. Layoffs, however, still remain low by historical standards—and negative labor market narratives like the “techcession” proved to be mostly about reduced hiring rates. Measured labor productivity also realized some historically large dividends as workers settled into their new jobs, supply constraints eased, and fixed investment recovered.

2023 was also a historic year for American housing markets. Significantly higher mortgage rates led to a credit crunch across the industry, with refinancing activity vaporized and purchasing applications down. The gap between existing homeowner’s 2-3% rate mortgages and the 6-8% rates for new mortgages throughout 2023 also constrained listing and selling volumes, although it isn’t likely to freeze the housing market as much as is often feared. Despite all this, housing prices continued making new highs—in large part thanks to an acute shortage of vacant units that is driving significant shifts in America’s economic geography.

This year also saw official confirmation that the pandemic era represented the largest wealth increase in modern American history and a rare decrease in wealth inequality, thanks in large part to the booming value of residential real estate. Stock and business ownership became significantly more widespread, and rent-inclusive debt payment burdens eased to the lowest levels in 30 years. However, the “excess savings” accumulated during the pandemic, while not completely exhausted, are now mostly inconsequential outside the upper echelons of the wealth distribution, and payment burdens are certainly up as interest rates have risen and student loan payments resumed over the last year.

Conclusions—Looking to 2024

Expectations for 2024 are much better than they were for 2023—the median FOMC member projects 1.4% GDP growth through 2024, and the median professional forecaster sees 1.3% growth. That’d still represent a slowdown and a period of below-normal expansion, which combined with the general deceleration in inflation is why markets are pricing in significant rate cuts for the year. Still, it’s nothing like the level of recession risks implied by many of last year’s forecasts—which means beating expectations for 2023 has now raised expectations for 2024.

Will you publish a 2024 forecast ?

Diamond Joe Biden is the Horace Bixby of presidents.