A Better Measure of the National Debt

Commonly Cited Measures of Government Debt are Incomplete and Misleading

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

In 1989 NYC real estate developer Seymour Durst erected a 286 square foot billboard in downtown Manhattan with a live projection of the national debt. That billboard has been bounced around New York, unplugged, and upgraded in the 30 years since its creation, but one thing remained constant: the simple measure of the national debt that it has used is incomplete to the point that it is almost misleading.

Actually getting an accurate measure of the federal debt is a surprisingly difficult endeavor as intragovernmental debt, the Federal Reserve’s holdings, and the federal government’s assets all complicate the picture. The debt is also usually compared to gross domestic product (GDP), a stock-to-flow comparison that creates an entirely new set of issues that need to be accounted for. However, there is one simple and clear measure of the national debt that provides the best picture of federal liabilities.

Properly Counting the National Debt

What's wrong with the headline number on Mr. Durst's debt clock? Technically, nothing. It is only the gross federal debt number published by the Department of the Treasury every week. In practicality, however, that gross number conceals a number of complications that make the true size of the national debt harder to glean.

The largest issue is with how the Treasury treats intragovernmental debt - debt that one department of the federal government owes to another department. The primary example, accounting for a slight majority of total intragovernmental debt, is the Social Security Trust Fund. When the Social Security Administration (SSA) takes in more money in payroll taxes than it disburses in benefits it puts that money in the Social Security Trust Fund and “buys” special issue bonds from the Department of the Treasury. The Treasury then pays interest on these bonds back to the Trust Fund and allows the SSA to exchange the bonds for money if benefits exceed payroll tax revenue in a given year. The money in the Trust Fund shows up as “debt” for the Department of the Treasury and the federal government as a whole, but this is merely a legal and accounting trick. It is the equivalent of saying that your checking account owes money to your savings account. The federal government can't owe itself money, so intragovernmental debt ought to be be excluded when measuring the debt. This is no small change either; the Social Security Trust Fund is almost $3 Trillion, and total debt held by agency trusts is $6 Trillion (besides Social Security the majority is held in federal employee and military retirement funds).

There’s another related problem: The Federal Reserve. Since 2008, the Federal Reserve has engaged in Quantitative Easing (QE), a program where the Federal Reserve purchases government debt using a special kind of inter-bank money called reserves to lower long term interest rates and stimulate the economy. The Federal Reserve is not technically an arm of the US government, but it is required to remit all the profits it makes on its balance sheet back to the government. In effect, if the federal government pays interest to the Federal Reserve the Federal Reserve must pay that money right back to the federal government. We’re essentially back in the same situation as the Social Security Trust Fund, where the debt is a legal and accounting trick more than a real liability.

The one complication is the other policy that came alongside QE - Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER) and Interest on Required Reserves (IORR). The Federal Reserve used to maintain control of interest rates through the quantity of reserves, but since QE dramatically increased the quantity of reserves in the banking system they instead needed to dictate interest rate policy through IOER and IORR. This essentially turned reserves into another form of government debt that never technically matures. Some measures of the national debt therefore include reserves alongside the physical coins and bills that together make up the monetary base.

The graph above shows four different measures of national debt divided by GDP. Gross federal debt/GDP is the headline figure that would be displayed on the debt clock and the Department of the Treasury website. The second measure, marketable debt/GDP, represents all publicly-traded treasury securities. This includes the Federal Reserve’s holdings but excludes intragovernmental holdings. Privately held debt including reserves/GDP is the most complicated measure, as it excludes all Treasury securities held by the Federal Reserve but includes reserves and non-marketable debt (mostly the series I and EE savings bonds that your Grandmother probably got you when you were a kid). Finally, privately held debt includes only marketable securities held outside the Federal Reserve and the small savings bonds held by individuals, excluding reserves entirely.

Two interesting things to note before moving on. First, until 1960 privately held debt was substantially larger than marketable debt. While the difference between privately held debt and marketable debt nowadays is almost entirely the Federal Reserve’s holdings, I believe the gap from 1950-1960 represents WWII war bonds that eventually all matured. Secondly, if you look at the small gap between privately held debt including reserves and marketable debt starting in 2008 you can actually see the effects of the Federal Reserve’s massive purchases of Mortgage Backed Securities. Since the Federal Reserve was issuing reserves and buying private debt instead of government debt, these items diverge for a short time.

The core insight of these measures is that, no matter which way you slice it, gross debt significantly overstates the actual size of the federal debt. I personally believe that privately held debt including reserves is the best measure of the national debt, as it includes every financial instrument held by members of the public that the federal government pays interest on.

One thing that is rarely accounted for in discussions of the federal debt is federal assets. Any time the federal government purchases a durable good, lends money to businesses and individuals, or invests in capital projects it is increasing its assets. In 2008, when higher education enrollment shot up in response to the Great Recession, the federal government was essentially borrowing money and turning around to lend it at a higher rate every time it made a student loan. Looking at the national debt alone would have made it appear as though the government was going deeper in debt when in actuality the government’s financial position was improving.

The graph above shows all the same measures as the last graph, adjusted for total federal assets. The new measure, gross net federal liabilities/GDP, is the Department of the Treasury’s official figure for the governments net worth. This accounts for other measures of debt (unpaid bills, IMF special drawing rights, etc) but still treats intragovernmental debt as a liability only. Remarkably, by some metrics the government’s net worth was positive until about the mid 1980s. The increase in federal liabilities looks starker in this context, but the actual size of the national debt is significantly smaller. It is also worth noting that this is an incomplete measure of national assets, as the massive landholdings of the federal government are ignored.

All of these measures, however, share a common problem: stock-to-flow comparison. The national debt is a stock, meaning a measurement at a single point in time of a quantity that accumulated in the past. GDP is a flow, meaning it represents an activity that occurs across time. As an example, think of a car. The amount of gasoline in the car’s tank is a stock, while the speed of the car is a flow. Dividing the amount of gasoline in your tank by the speed of your car does not tell you almost anything about the status of your trip. Instead, you have to compare stocks to stocks (i.e. the amount of gasoline in the tank compared to how far away your destination is) or flows to flows (the speed of the car to the speed of gasoline consumption) to make meaningful comparisons.

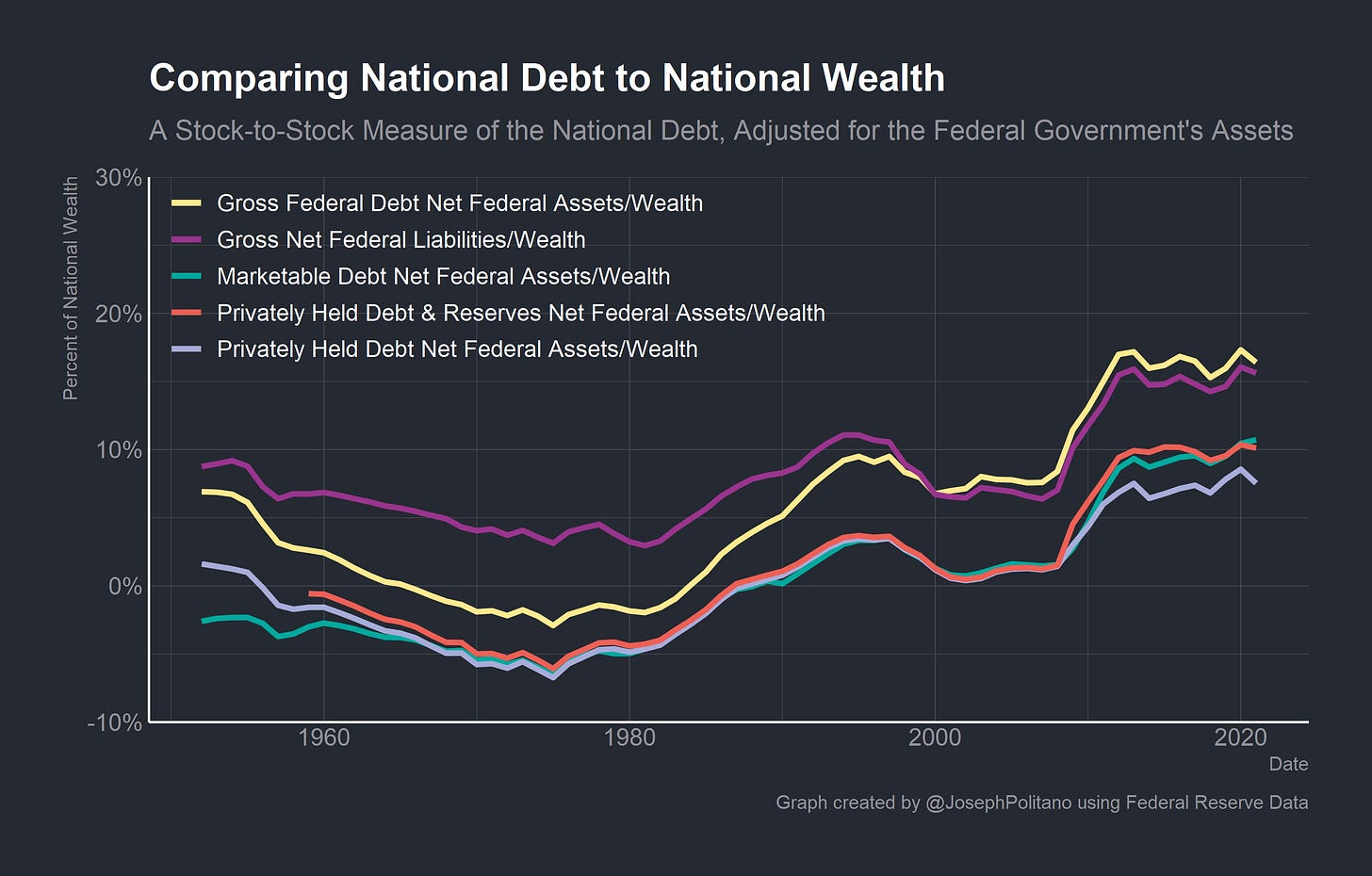

Comparing National Debt to National Wealth

The graph above accounts is a stock-to-stock comparison: the national debt is divided by the national wealth. It is worth noting that the federal debt held by US households and businesses are not counted as net wealth - they are counted as liabilities of the government and assets of the people, cancelling out in the aggregate figure. Federal liabilities to people in other countries are, however, a liability to the US as a whole.

The stock-to-stock measure is an improvement in several areas. First, it captures a relevant mechanism that debt/GDP distorts: wealth and debt have both tended to increase faster than GDP. This is partly due to the tendency for the return on capital (analogous to the net growth of wealth) to be larger than the growth rate of the economy. This is the r>g relationship popularized by Thomas Piketty. The second is that we have been in a long era of declining real interest rates. As interest rates decline, the value of capital (including pre-existing debt) increases. While this does cause higher measured wealth values, it does not directly cause increased debt values. Rather, lower interest rates enable the government to borrow more for the same cost in terms of interest paid, and the American government has tended to take advantage of this.

The debt to wealth measures also demonstrate that the national debt remains within historical levels, although somewhat elevated since 2008. Critically, the debt to wealth ratio barely moved in response to the 2020 recession as declining interest rates and extraordinary government spending maintained income growth and allowed for an increase in wealth several times larger than the increase in national debt. The core lesson of that should be that additional federal spending can lower the actual debt burden by increasing wealth and GDP more than it increases debt. This is the fiscal multiplier, and while it does not apply always and everywhere it extremely clearly applies when the economy remains below full employment and maximum growth. The core problem of the 2008 recession was that tight monetary policy and insufficiently expansionary fiscal policy allowed GDP, national wealth, and employment to decline precipitously. In such a case, borrowing money to support incomes and nominal GDP would have both increased economic growth and lowered the debt burden.

The graph above shows different measures of the debt net federal assets as a percentage of national wealth. While these measures show significantly lower debt burdens, the increase in national liabilities since the 1980s is significantly starker.

However, there are still several problems that remain with the stock-to-stock comparison of debt and wealth. For one, accurately measuring national wealth is a difficult task. Every individual home, car, washing machine, factory, and piece of equipment has to be assigned a value for accounting purposes. I do not doubt that the Federal Reserve’s measures are as accurate as humanly possible, but I am certain that significant imprecision comes from trying to estimate the value of non-fungible infrequently exchanged capital goods. Additionally, assigning aggregate values to capital is an extremely difficult task. The heterogenous nature of capital goods, financial assets, and their associated risks and returns means that assigning aggregate values to capital requires a level of amalgamation that makes meaningful analysis almost impossible. I will not relitigate the entire Cambridge Capital Controversy here, but suffice to say that national wealth is a far from ideal measure even with perfect accounting.

So if stock-to-stock comparisons fail, the only option we’re left with is flow-to-flow measures of the national debt. Luckily, these measures provide the simplest, clearest, and most meaningful measure of the national debt.

The Best Measure of the National Debt

The graph above shows two different measures of total interest expenses paid by the federal government divided by GDP. Essentially, this represents the total amount of money spent by the federal government to service the national debt as a share of America’s total economic output. The first measure represents the gross interest paid by the federal government, while the second measure represents interest net the money remitted by the Federal Reserve to the Department of the Treasury. These remittances are the difference between the income the Federal Reserve receives on its portfolio of mostly Treasury securities and the interest it pays on reserves. Since the Federal Reserve is required to remit any profits it receives, the money the Department of the Treasury pays on securities held by the Fed is not true interest expense. Only the interest paid on reserves, which are held by private banks, is actually a form of government interest expense. The Federal Reserve almost always takes in more money from the Treasury than it gives out to private banks because Treasury bonds are riskier long term assets that pay higher interest rates than low risk short term reserves. Since these profits remitted to the Treasury represent the gap between interest paid to the public on reserves and interest paid to the Federal Reserve on treasuries, subtracting remittances from federal interest expenses generates the government’s total net interest expenses to the public.

By tracking only the cost to service the debt, these measures capture the most critical element of the national debt. The federal government is not like a household; it never dies or retires and never has to fully pay off its debt. In actuality, the federal government should almost always be expanding its debt to make investments that would increase the GDP more than they would increase the government’s interest costs. Since it only needs to continually repay the interest as it rolls over old debt and borrows additional money, net interest expenses as a share of the economy represent the clearest measure of the size of the debt.

This also has the added advantage of bypassing the arbitrary decisions necessary in determining an aggregate measure of the size of the debt itself. For example, it is worth thinking about the specifics of Social Security and other various entitlement programs. When the US government borrows money, it is promising someone to pay a defined sum at a certain point in the future. Through Social Security benefits, the government is also promising someone to pay a defined sum at a certain point in the future. There is no philosophical difference between these two (except that the federal government has a more meaningful ability to legally change future social security payments than future bond payments), but one is measured as debt and the other is not. On the asset side, think about student loans. Why are student loans, money that American citizens have agreed to pay to the federal government in the future, considered assets while income taxes, which are also money that US citizens have agreed to pay the federal government in the future, are not? There are measures that attempt to account for these discrepancies, but fundamentally they do so by making arbitrary decisions about what is or is not debt. The best answer to this problem is the simplest: just look at how much it costs to maintain the federal government’s liabilities to the public.

Interest expenses have hovered between one and two percent of GDP for the vast majority of America’s post-WWII history. There were two significant exceptions: when net interest expenses increased dramatically between 1980 and 2000 and after 2008 when net interest expenses shrank substantially. The crisis of rising interest costs maps well onto when policymakers focused heavily on lowering the federal debt, culminating in the federal surpluses during the Clinton administration. Post-2008, the decline in net interest expenses coincides with a greater focus on weak aggregate demand and economic growth than on the size of the federal debt. Indeed, it would have been beneficial during both the 2008 and 2020 recessions to point out to those opposing federal debt-driven stimulus that the benefits to spending were high and the costs were incredibly low.

Despite the gross size of the debt increasing dramatically, the current cost to service the debt remains well below the highs of 1990 and within historical averages. In fact, interest expenses net remittances reached their historical lows in 2017. Interest expenses are still sensitive to short term shifts in interest rates since Treasury notes (debt with maturities between 1-10 years) make up the majority of federal debt, so measuring the stock of federal debt can be useful in forecasting future interest expenses. However, it is high time we moved on from the gross figures on billboards and focused on the data points that truly matter.