A Detailed Look at Biden’s New China Tariffs

Breaking Down the Data on the White House’s Increased Tariffs for Chinese EVs, Solar, Batteries, and More

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 42,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Last week, the Biden administration announced a series of increased tariffs on various Chinese goods, representing yet another escalation of the US-China trade war that has now been raging on for the better part of a decade. The move was obviously partly political—it is, after all, an election year, and several of the industries protected by new tariffs have outsized influence in midwestern swing states—but it also represented a further intensifying of America’s more active post-COVID industrial policy.

The tariffs were largely designed to protect the sectors boosted by America’s two major industrial policy bills—the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act—while guarding against the recent surge in Chinese net exports. Policymakers have gambled that American industry can quickly match the complexity and scale of China’s supply chain across a variety of key sectors and are hoping trade restrictions can give domestic manufacturers more room to catch up. Broadly, the new tariffs can fit into three categories—preemptive changes to defend the status quo in key green industries, targeted measures to decouple the US from Chinese batteries, and a grab-bag of tariffs to protect key “national security” sectors.

Type 1: Enforcing the Status Quo

Many of the tariffs announced last week will have nearly zero short-term impact because the US is, at least nominally, already entirely decoupled from Chinese imports within those industries. Instead, these tariffs were deployed as preventative measures to ensure Chinese goods in key cleantech sectors don’t break through existing trade restrictions—in other words, they are aimed at defending, not reshaping, the existing trade status quo.

Take the new 100% tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, which got a dominating share of the news coverage. China is now by far the world’s largest producer and exporter of EVs, but the tariffs and trade restrictions in place before this week meant that the US already imports extremely few EVs from China. Even as total US EV imports grew after subsidies passed under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), purchases of Chinese-made electric vehicles shrunk to less than 2% of gross US EV imports last year. The tariff hike was thus aimed at reinforcing that status quo—ensuring Chinese EVs remain excluded from US markets even if they dipped in price enough to overcome the preexisting 25% tariffs and other trade restrictions.

The same pattern holds true in solar—although China is by far the number one global producer of solar panels and the solar cells that compose them, existing tariffs mean that the US already imports essentially all its solar from elsewhere in Southeast Asia. Much of these imports represent subsidiaries of Chinese firms that are integrated to varying degrees with the mainland solar supply chain, but they are manufactured and exported from factories that would not be subject to these new China tariffs. Again, this was primarily a preventative measure aimed at maintaining the status quo and ensuring the ongoing price drops in Chinese cleantech goods do not overcome existing US tariffs.

The more important action on the solar panel front thus came from an antidumping investigation opened by the Department of Commerce into solar imports from Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, and Cambodia. Prices for solar panels deployed in the US have dropped more than 20% over the last year after surging in 2022’s energy crisis, and that price drop has left domestic manufacturers struggling to compete. The anti-dumping investigation was also coupled with the ending of a tariff exemption that had covered those Southeast Asian nations over the last 2 years—in other words, even though tariffs on Chinese solar won’t have much of a short-term impact, an increase in solar costs can still be expected from other trade restrictions.

Previous rounds of solar tariffs have failed to increase domestic production, although this time there is a significant amount of American solar panel, cell, and wafer manufacturing capacity in the works as a result of IRA subsidies. Still, since solar modules represent roughly half the cost of utility-scale solar deployments in the US trade restrictions risk hampering the clean energy buildout unless American manufacturers can become cost-competitive very quickly.

Returning to China, long-standing US trade policy has been to functionally exclude Chinese-made EVs and solar panels from American markets. It should not be surprising, nor is it much of a change, when the US places further tariffs on those goods to maintain that status quo. But to the extent these new tariffs are more than just political theater, they signal that America’s solar and EV industries are falling so far behind that they legitimately feared Chinese manufacturers could’ve outcompeted them despite all the trade protections they already enjoyed before last week.

Type 2: Challenging China on Batteries

While much less covered than the EV tariffs, the most impactful type of tariffs came in the battery supply chain—taxes on Chinese lithium-ion batteries, natural graphite, permanent magnets, and a suite of critical minerals were all raised. Here, unlike in EVs and solar, the US currently does have an extremely deep connection with the Chinese supply chains that dominate global battery production. On net, America imported more than $15B in Chinese batteries in 2023, a record high that easily dwarfed net imports from any other country.

First, the tariff rate on Chinese EV batteries will rise from 7.5% to 25% this year. That matters tremendously because China is by far the largest source of foreign EV batteries, representing roughly two-thirds of gross US imports in 2023. Tariffs here are building on the battery sourcing requirements from the IRA, which mandated that EVs could not use battery components from China and other “foreign entities of concern” if they wanted to qualify for tax credits. Those rules came into effect this year, but so far have only slowed the growth of Chinese EV battery imports, which still stood at more than $2.5B over the last 12 months. That’s partially because Chinese batteries are so much more cost-competitive than their competitors, and partially because the stringent battery sourcing requirements only apply to tax credits for EV purchases—EVs with Chinese batteries can still qualify for certain tax credits when leased. The new tariffs will immediately add additional costs to the American car manufacturers that still use Chinese EV batteries in their supply chains while further incentivizing domestic production and non-Chinese imports.

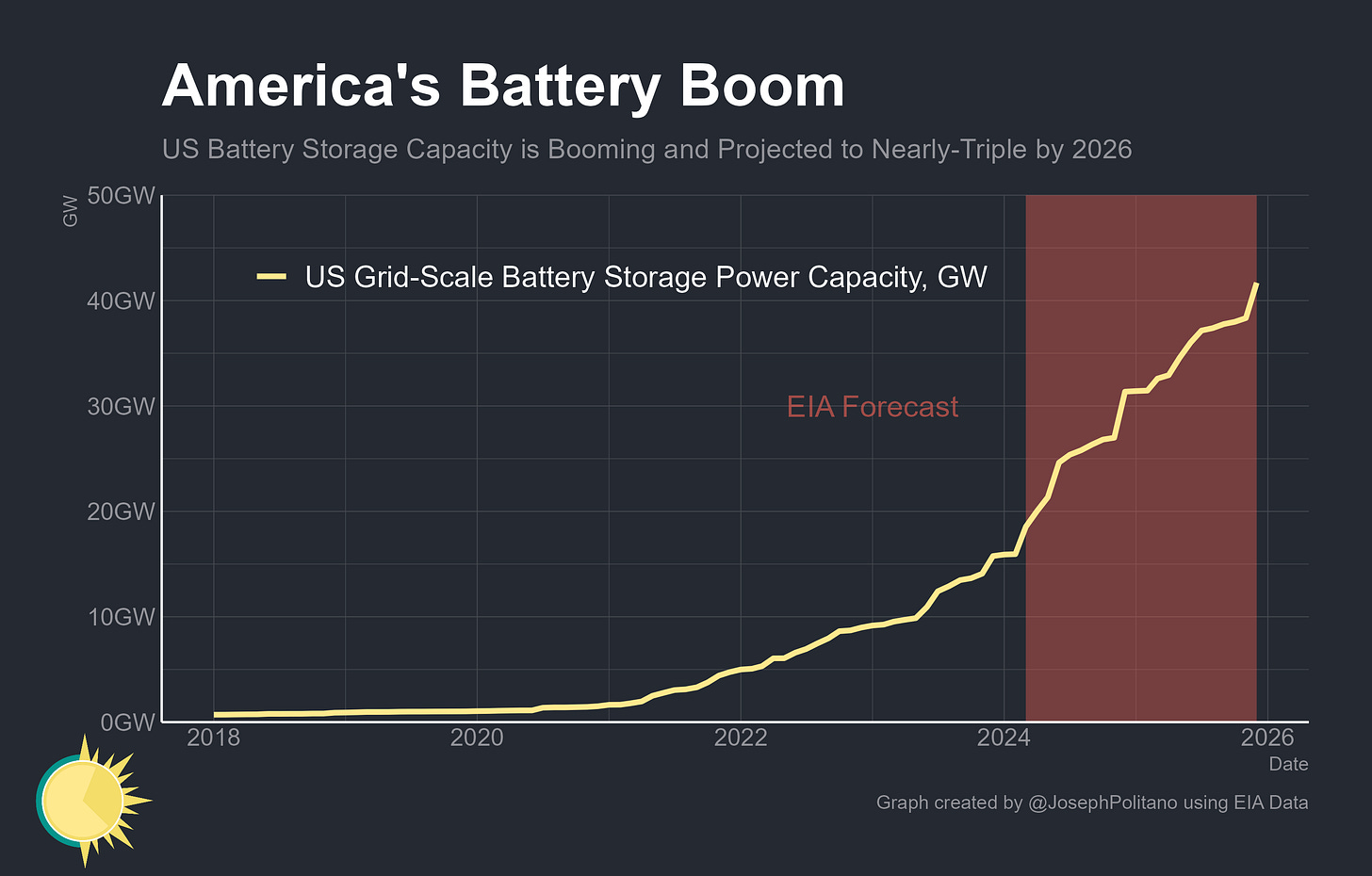

Second, the tariff rate on non-EV batteries will increase from 7.5% to 25%, mostly affecting the large utility-scale batteries increasingly deployed throughout the US power grid. These battery facilities are often built to complement new solar and wind farms since electricity storage helps offset many disadvantages of intermittent power resources, and their current pace of construction is hard to overstate. US battery storage capacity has tripled since 2022 and is projected to see another near-tripling over the next two years. For this reason, tariffs in this subsector won’t come into force until 2026, allowing some space for current construction projects to be completed undisturbed—yet this will almost certainly be the single-largest item affected by last week’s announcement when all tariffs do go into effect.

The battery tariffs themselves were also paired with tariffs on related cleantech components like permanent magnets (which are key to electric motors/generators) and natural graphite (which is a fundamental anode material for rechargeable batteries). For both goods, the US is currently highly dependent on China, which represents more than 70% of all imports. Tariffs here will rise from 0 to 25% in 2026, again providing some time for suppliers to attempt the challenging task of diversifying away from the dominating Chinese supply chains.

Finally, tariffs on a selection of Chinese “critical minerals” will rise from 0 to 25% this year. This will likely cover an extremely wide list of goods—2021’s Executive Order 14017 on supply chain security identified more than 271 separate categories of critical minerals, more than $2B of which are imported from China. The degree of Chinese dependency varies significantly, but for some key inputs it is extremely high—in subcategories like unwrought tungsten, zirconium powders, and select rare-earth metals, China makes up more than 90% of US imports, and in roughly 17 critical mineral categories China makes up at least half of American imports.

All these tariffs represent a significant gamble that the US battery supply chain can grow to meet domestic needs over a relatively short timeframe. So far, real US battery production has risen more than 25% since the passage of the IRA in late 2022, and employment in the sector is up roughly 10% over the same period. Yet that growth has still not been nearly enough to meet domestic demand—in 2023, US manufacturers’ battery shipments totaled $15.8B while net imports totaled $23.9B. The US has tens of billions in battery manufacturing capacity currently under construction, but America’s battery industry would still have to grow significantly faster just to replace current Chinese imports, let alone to meet increasing demand from rising cleantech deployment.

Type 3: Protecting Other “National Security” Industries

Finally, the last type of new tariffs represents a continuation and escalation of trade restrictions for “national security” purposes. The tariffs here primarily covered more politically salient “dual-use” goods that have both defense and commercial applications, but they also loosely fit into some of America’s broader industrial policy goals. Take the increased tariffs on Chinese iron, steel, and aluminum, which will rise to 25% this year—metals have long been a focus of national security policymaking because of their importance to defense manufacturing and have long been a political focus because of their importance in swing states like Pennsylvania and Ohio. In 2023, China made up less than 1.8% of US steel & iron imports, but in aluminum it was a much bulkier 9.4% of all imports. Tariffs on articles made of steel & iron could also be extremely important depending on the yet-to-be-released details, as there China represents more than 1/5 of US imports.

There was also an increase in tariffs on Chinese semiconductors, which were previously set at 25% during the Trump administration and will rise to 50% next year. Those already-existing semiconductor tariffs meant that less than $2B in Chinese chips were directly imported to the US last year, and imports have recently declined to some of the lowest levels outside the early pandemic despite China’s rapidly growing chip industry. Rising tariffs are likely to reduce imports even further, representing another move in the continually escalating semiconductor trade war between the US and China.

Finally, there was a grab bag of smaller sectors affected by tariffs. Tariffs on Chinese ship-to-shore cranes used at cargo ports will rise 25% this year, and tariffs on a variety of Chinese medical goods including syringes, needles, facemasks, respirators, and more were also raised. All these goods became essential items during the pandemic and were imported en masse from China, so policymakers are now looking to reduce foreign dependency and build out a domestic industry that can be called upon in the event of another pandemic.

Conclusions

These recent tariffs are part of a wider global trend towards more protectionism, particularly directed at China and particularly concentrated in cleantech industries. Just look to the European Union, which is currently enmeshed in a trade probe into the Chinese EVs that have gained significant market share on the continent and are cutting into the EU’s prized vehicle trade surplus. That’s in addition to other EU trade probes into Chinese wind turbines, tinplate steel, medical devices, and more which are also underway.

Yet so far, this global trend has only driven a marginal slowdown in the Chinese cleantech industry itself. The most recent monthly estimates show that Chinese production of New Energy Vehicles (NEVs, representing both EVs and plug-in hybrids) was 39% higher than this time last year and 157% higher than in 2022. At the end of 2023, China was manufacturing more than 1M NEVs per month, an amount roughly in line with the total level of all US vehicle production.

Chinese production of solar cells is likewise up 11% over the last year and 115% since 2022, although there was a significant slowdown in April. Production of semiconductors is also up nearly 32% over the last year despite efforts by the US to constrain China’s chip industry. So far, trade restrictions have perhaps slowed, but they have definitely not debilitated, Chinese manufacturers.

Domestically, the end goal of Biden’s industrial policy has been to build a durable coalition for manufacturing, particularly in the cleantech and electronics sectors—that’s why policies have been much more carrot than stick and have been coupled with populist compromises like increased tariffs. However, recent US industrial policy has not been able to increase domestic manufacturing productivity, nor have America’s prior rounds of Chinese trade restrictions. Many of the new tariffs will also be hitting goods like solar panels and grid-scale batteries that are fixed assets with long-term returns, not consumer products—and thus trade restrictions risk cutting down on valuable investment in clean electricity generation. China is also likely to retaliate in response to last week’s moves, and they could cause significant damage to the American cleantech manufacturing buildout by restricting exports of the machinery and equipment critical to battery, EV, and solar manufacturing.

If escalating subsidies and tariffs end up onshoring supply chains by overpaying for inefficient operations, they may have improved national security and helped decarbonize the US economy—but industrial policy will not have succeeded at rebuilding a genuinely competitive and dynamic American manufacturing sector. Biden’s new China tariffs have bought even more protective cover for American industry to catch up, but unless it does so quickly the US risks destructively isolating its economy further.

The last part about isolation needs to be emphasized too. The tariffs above 25% are illegal under WTO charter.

Great article.