A Global Energy Crisis is Worsening Inflation

Inflation is Running Hot Excluding Energy Prices. With them, it's Scorching.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 6,900 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

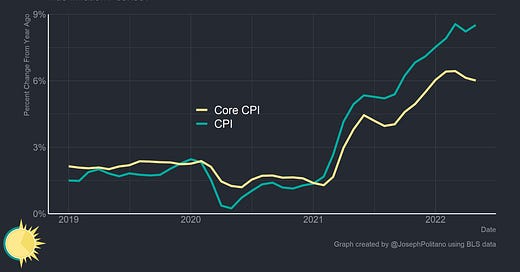

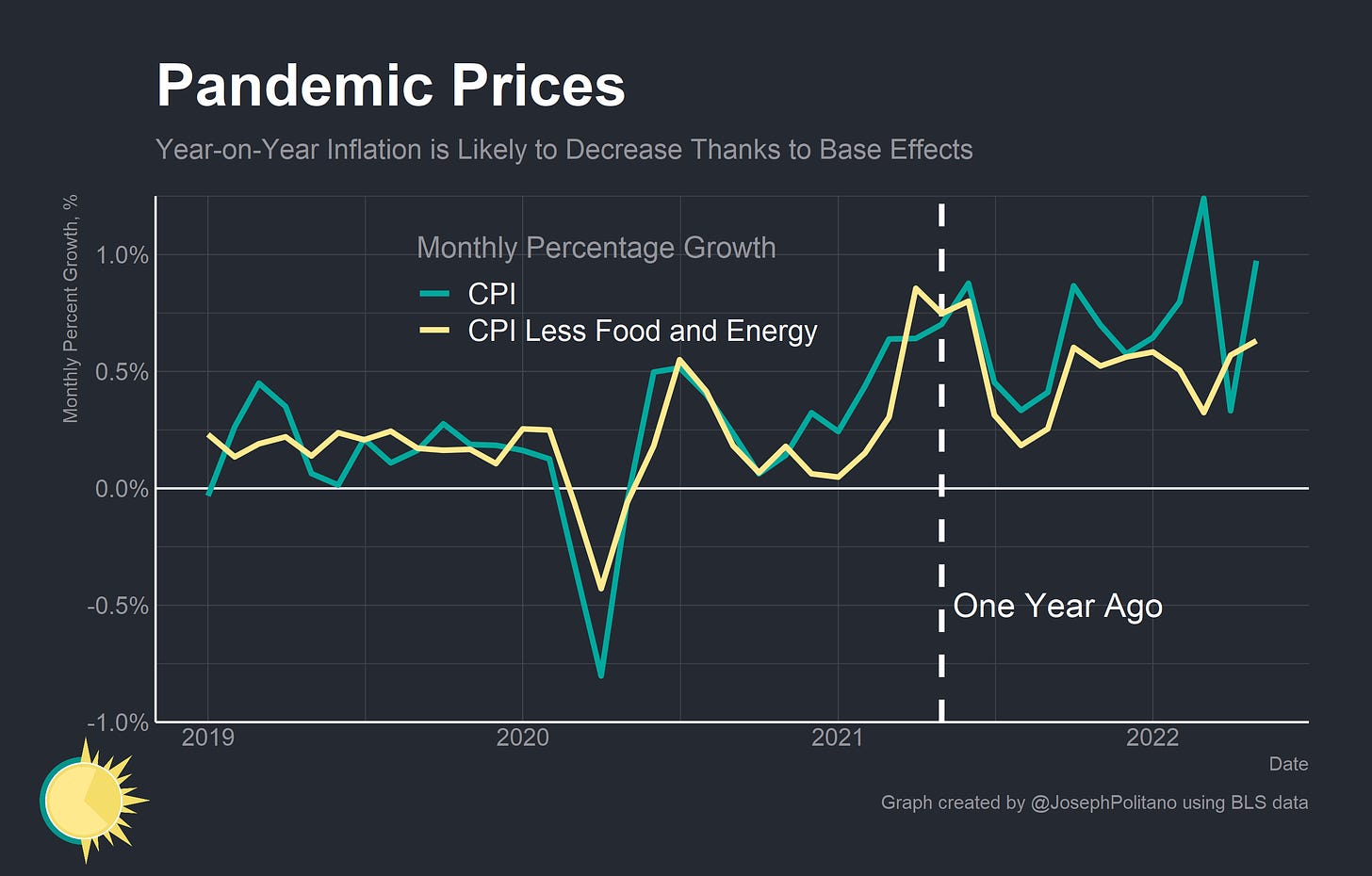

After dipping briefly last month, year-on-year growth in the Consumer Price Index inflation bounced back to 8.6% in May. On a monthly basis prices increased by a full percentage point—lead by rising shelter costs but supported by large increases in energy prices. Core inflation—which excludes food and energy—shrank back down to 6% on an annual basis but increased back up to 0.6% on a monthly basis.

The widening gap between core and headline inflation underscores the intensity of the energy supply shock facing America. Prices for gasoline, household utility gas service, and electricity were already high in 2021 and have only increased in 2022. The world was dealing with a significant output shortfall in a wide variety of energy commodities before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—and the situation has only gotten worse since then.

Rising energy costs present a unique challenge for policymakers—particularly as voters are extremely sensitive to the price of gasoline. But they also present another speedbump for monetary policy authorities—while the general advice is to look past supply shocks and ignore changes in gas prices, high overall inflation gives central banks less political capital to expend in tolerating price growth. The end result is a worsening economic outlook with heightened recession risks—making energy the center of attention for global economies.

The Energy Crunch

Gas prices are up nearly 50% since the start of 2020, and are currently more than double their early 2019 levels. Gasoline has been a massive driver of headline inflation over the last few months, and it doesn’t look like relief is on the way yet—crude prices are still increasing and higher-frequency measurements show prices at the pump rising alongside. Gas prices tend to be higher in the spring and summer as driving and other travel increase—and preexisting low levels of inventory mixed with pandemic-weary consumers travelling more might exacerbate the problem this year.

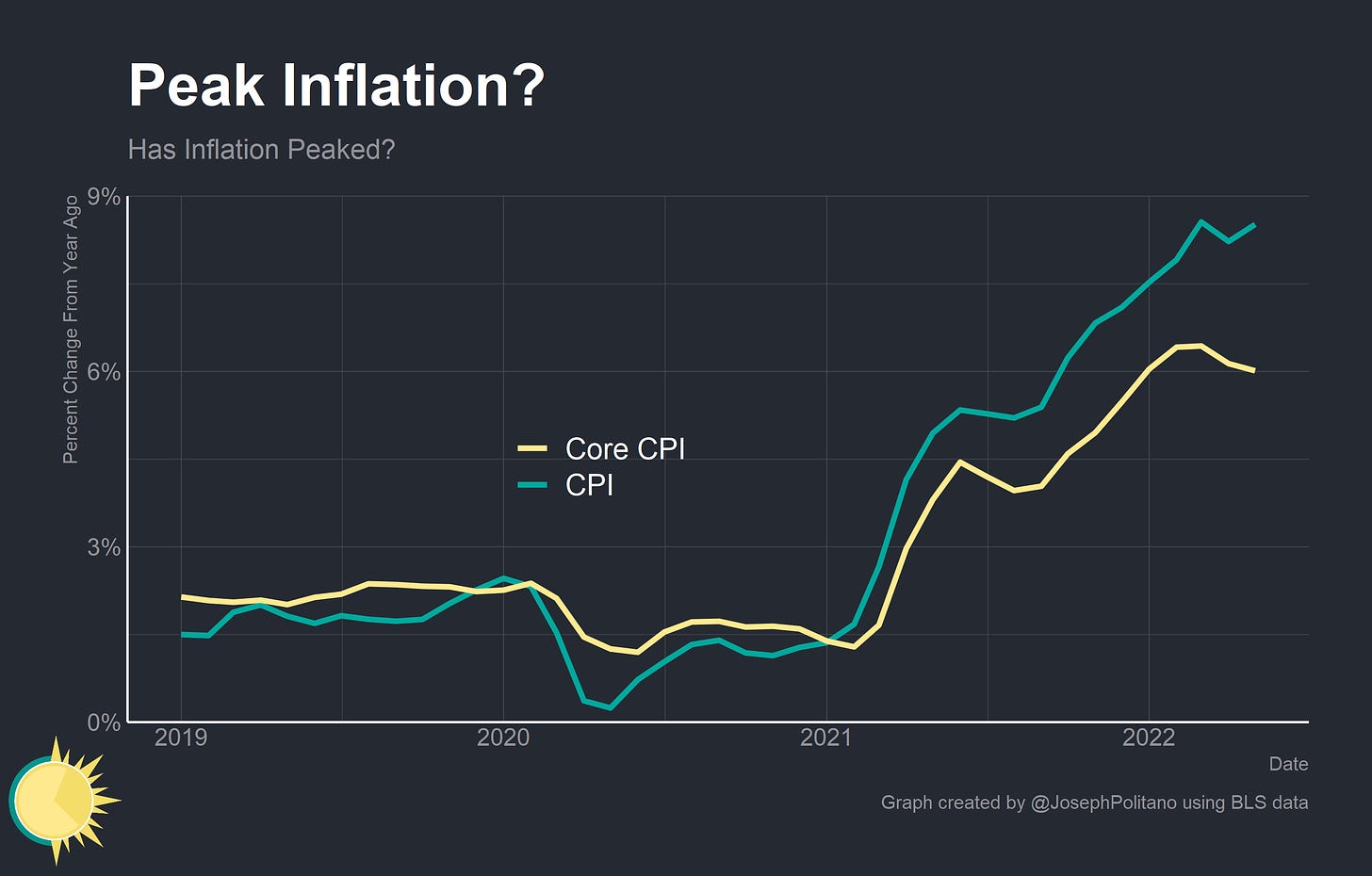

US production is still lagging, however. As a result of two price crashes over the last decade, domestic producers are increasingly reluctant to invest in capacity increases and are less responsive to price changes than ever before. Domestic supply chain and labor issues are also increasingly biting as restarting idled machinery and rehiring laid off workers proves difficult.

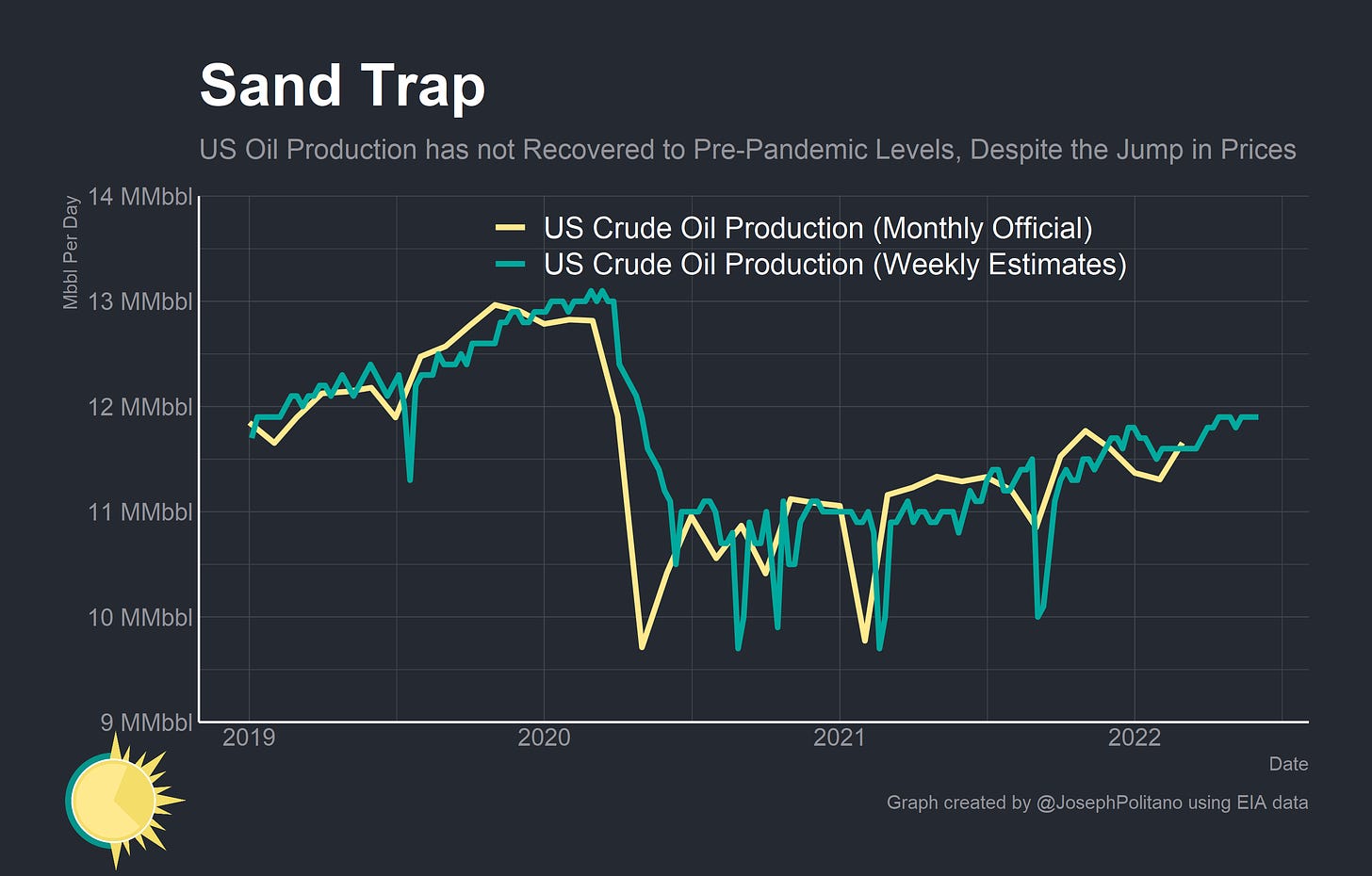

Global supply is also weak, with OPEC+ missing its production targets by 2.5 million barrels per day. Russian output alone is missing by more than a million barrels per day as the country deals with export sanctions that make sales harder and import sanctions that make production more difficult.

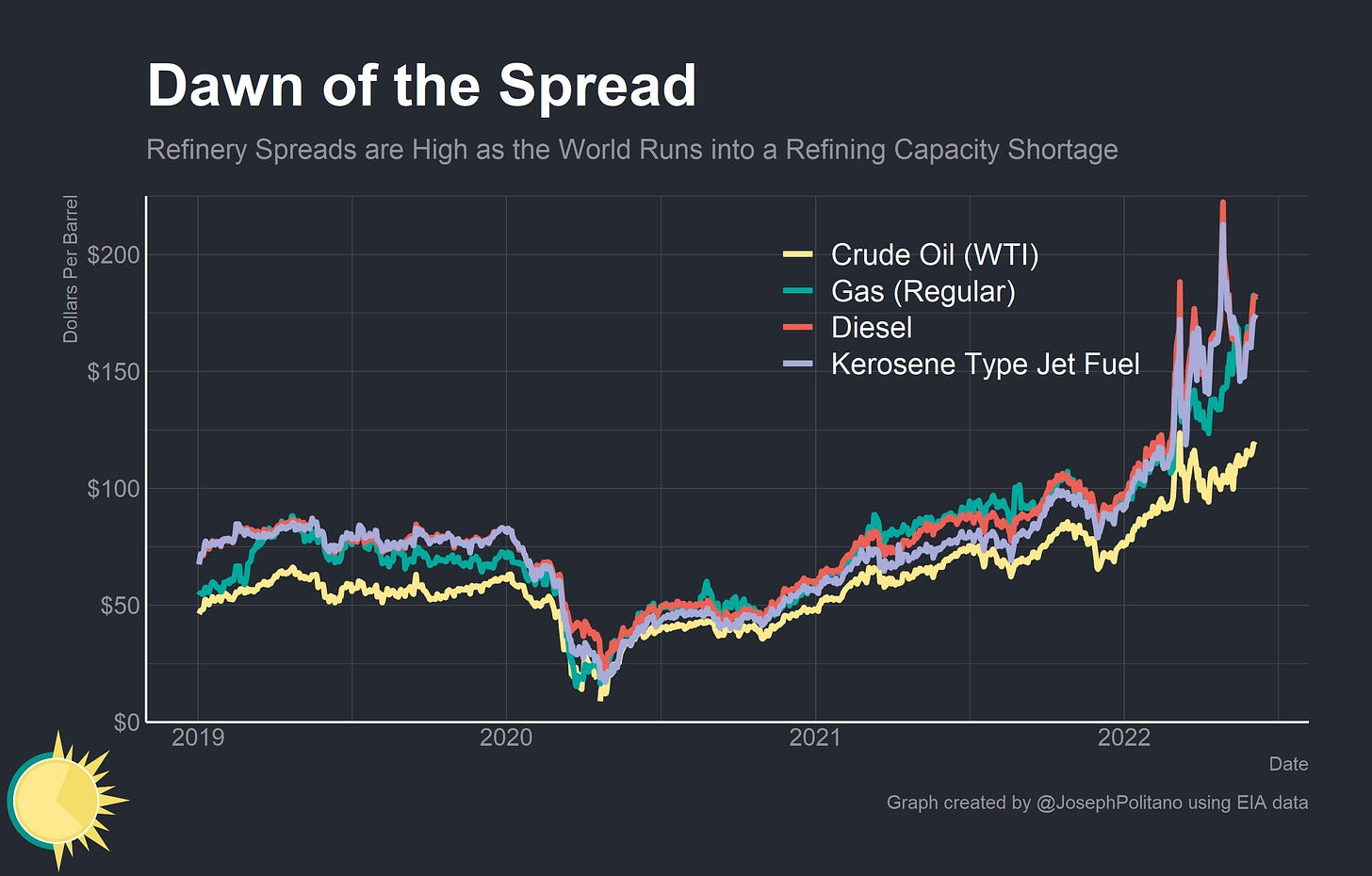

In addition, refinery spreads are rising as the world runs into an acute refining capacity shortage. Refineries—which convert crude oil into gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and other products—are in short supply thanks to a reduction of global capacity during the pandemic and the loss of access to Russian refineries.

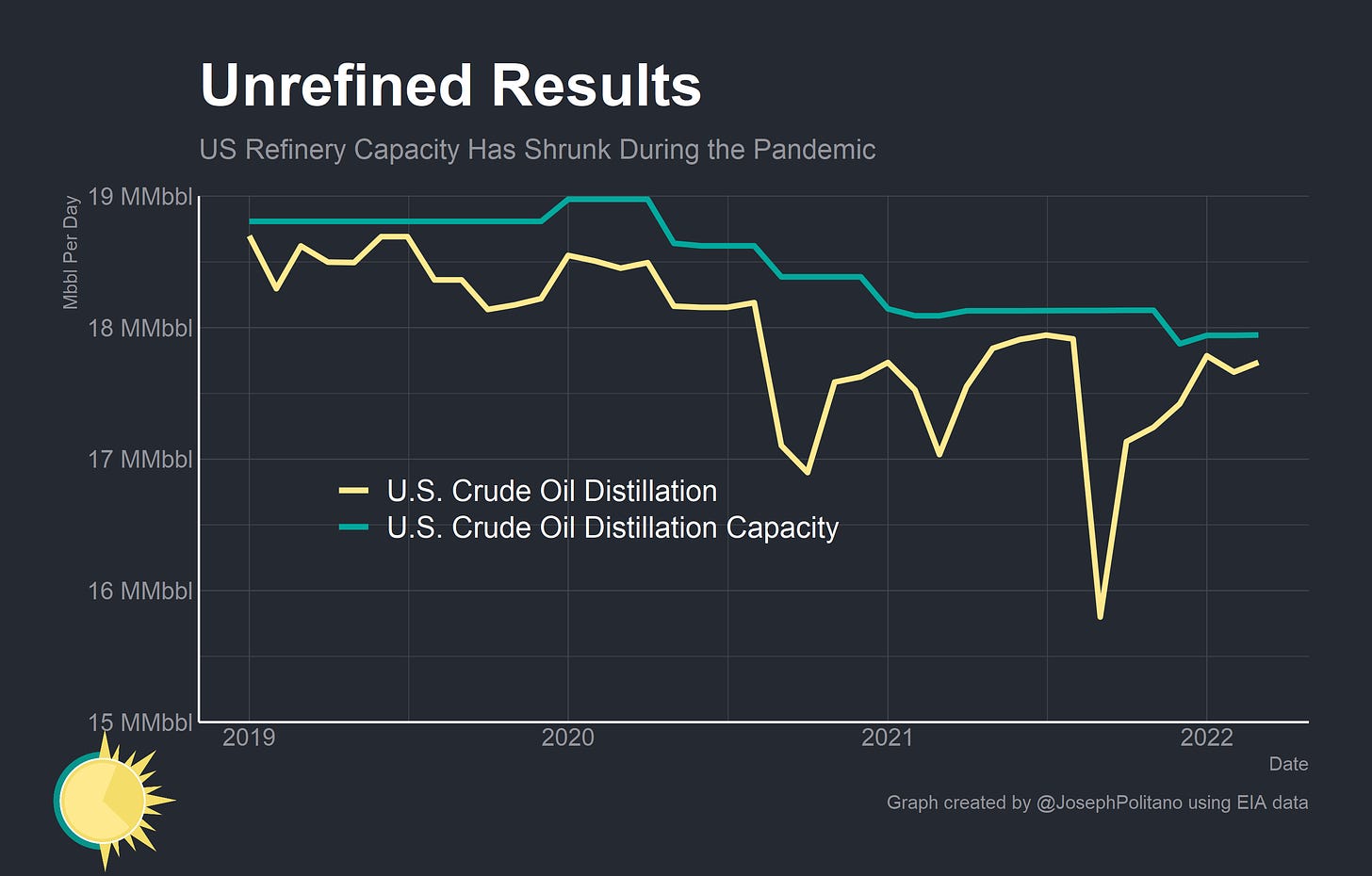

US refinery capacity steadily decreased about 5% since 2020 thanks to planned closures and relatively weak demand. Since the US is a net importer of crude oil and a net exporter of refined products, domestic refinery capacity is essential for global energy supply. A fire at a facility in Houston could bring more unwelcome news—possibly accelerating the planned closure of a facility that alone represents about 1% of US refinery capacity.

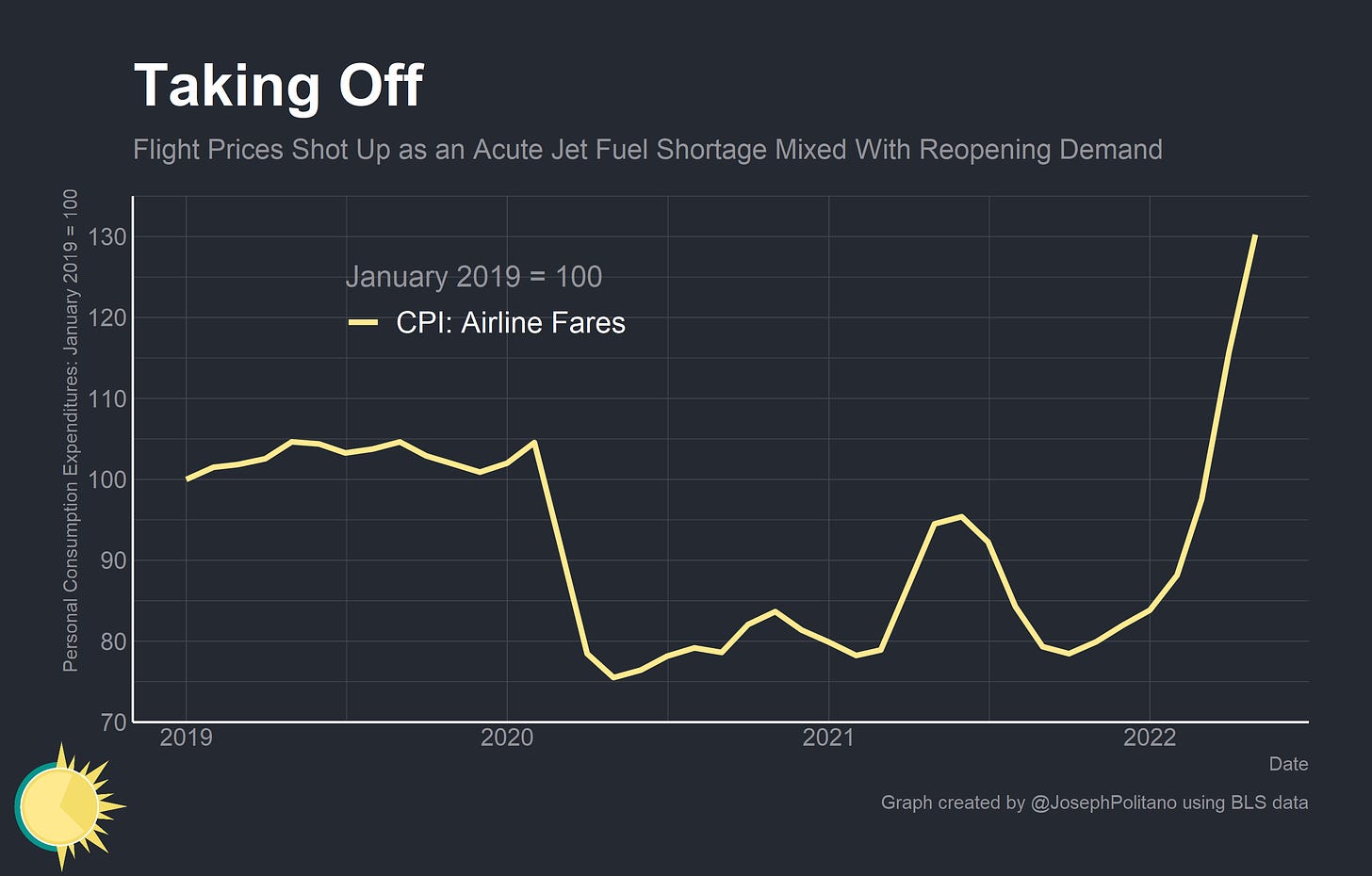

Jumps in refinery product prices are also affecting downstream prices. Take airfare prices, which have increased nearly 50% since the start of the year amidst a 75% increase in prices for kerosene jet fuel. This is all despite a 10% reduction in passenger throughput compared to pre-pandemic levels.

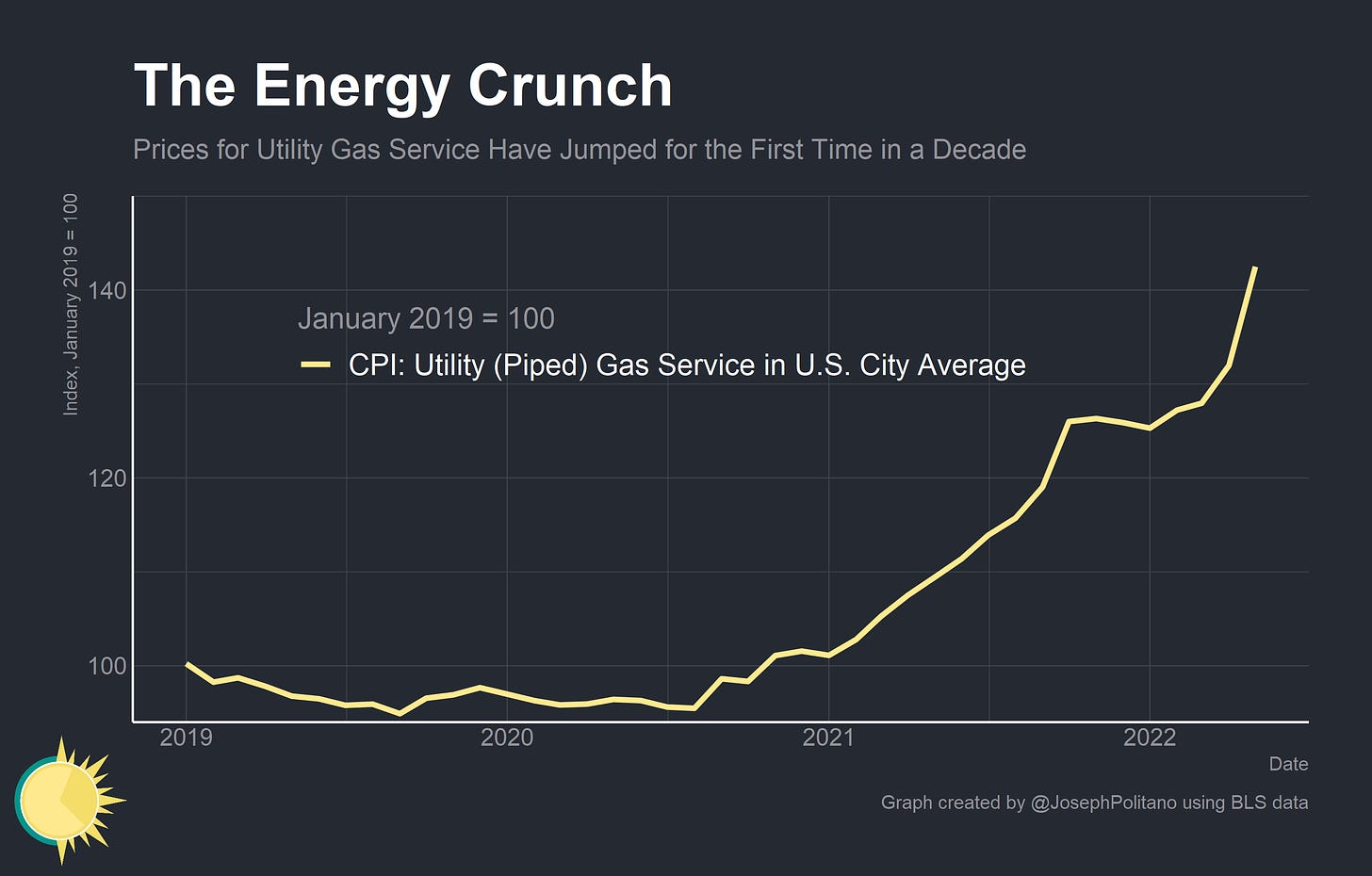

Prices for utility gas service are also increasing dramatically, jumping nearly 40% since the start of the year. This one is less about domestic supply than it is about foreign demand; American natural gas production has actually increased since 2019 but the US is exporting record amounts of Liquefied Natural Gas to Europe in order to compensate for lost Russian supply. Prices here likely have room to increase as well; Henry Hub spot natural gas prices are up more than 150% since the start of the year.

Even Without Gas, Inflation is Running Hot

What makes the energy shock harder to navigate is that underlying inflation continues to run hot even when excluding energy and food prices. Core inflation increased at a 0.6% annual rate in May—faster than any point in the last year. Some of that was passthrough from higher energy prices (for example, airfares are included in core inflation even though they are currently driven by jet fuel prices) but the bulk of it derived from growth in non-energy-related services.

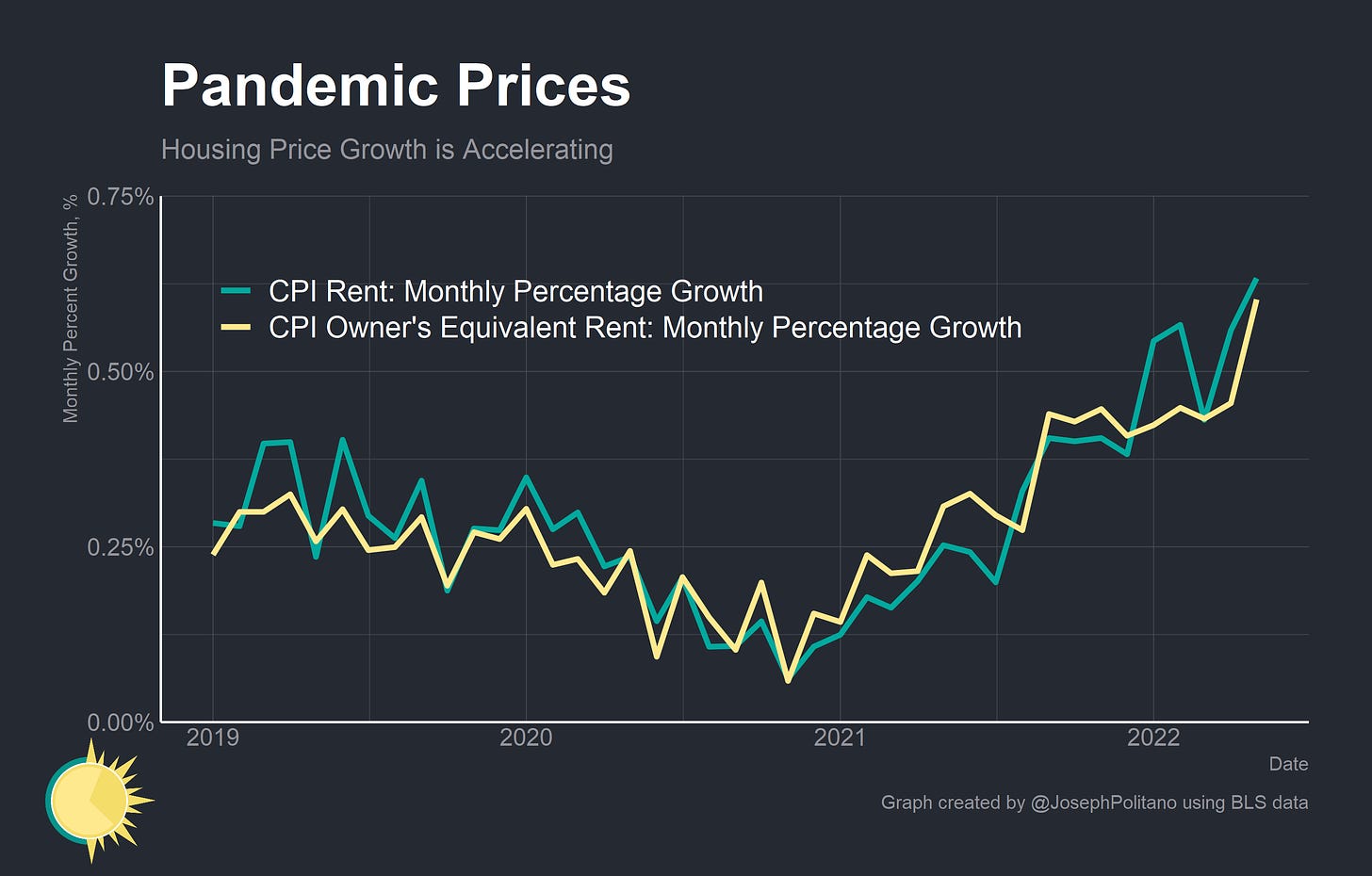

Take housing—monthly percentage growth for the rent and owner’s equivalent rent indices were at the highest level in more than 30 years. An average pre-pandemic monthly rent price index increase would be about 0.25%, and housing prices increased nearly 0.6% in May. The good news is that the worst might be behind us—monthly increases peaked this time last year in higher-frequency private-sector data from Zillow and other providers. Due to methodological differences, CPI data tends to lag these measure by approximately a year—which might make this the peak of monthly rent price growth in official data. However, data from Apartment List and Zillow show a slowdown in rent increases in 2022 compared to 2021 that still remains high by historical standards.

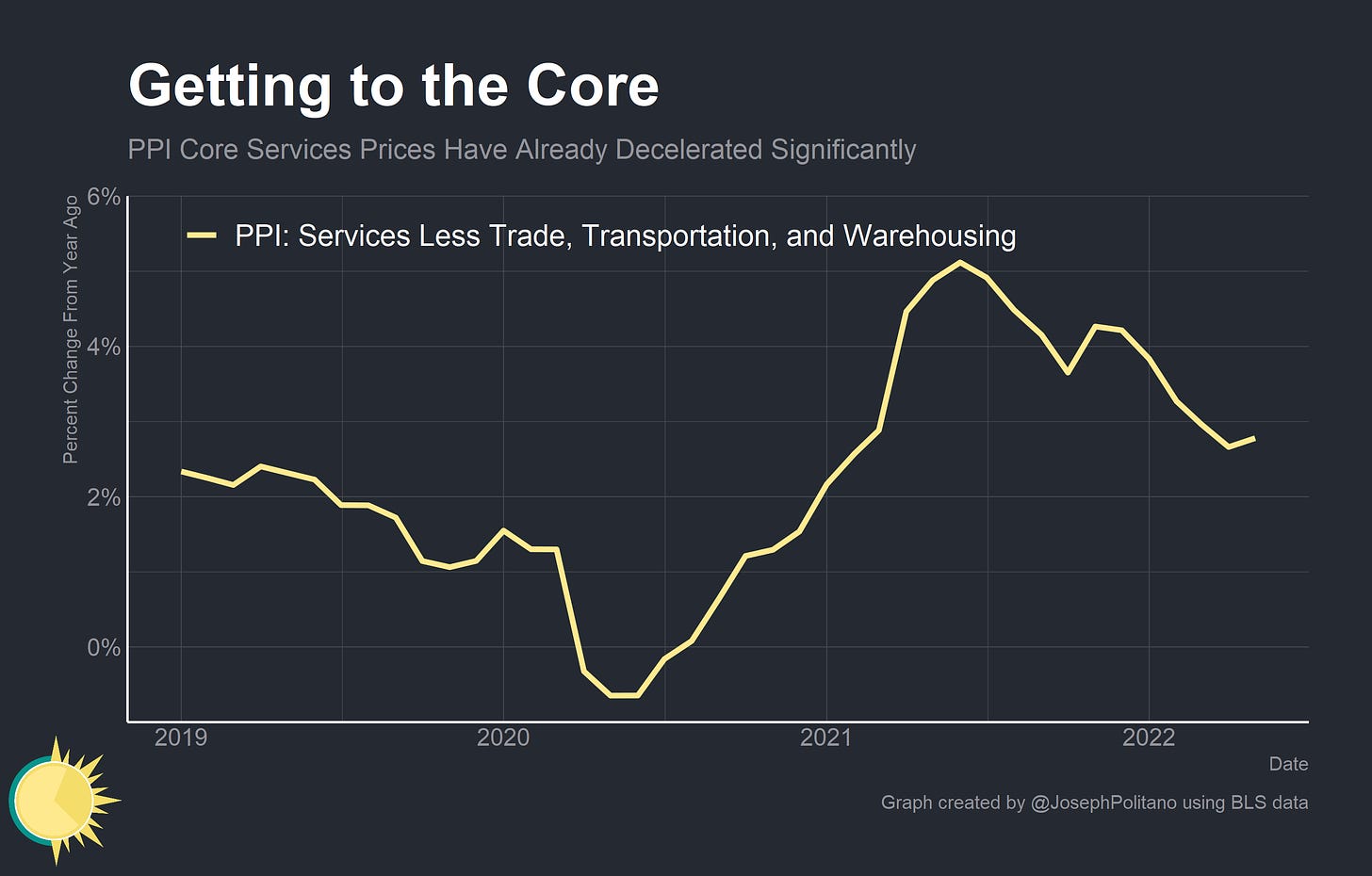

The other good news comes from the Producer Price Index. Price growth for core services—which can act as a proxy for underlying non-goods non-housing inflation—has stabilized slightly above normal levels. But with goods and housing inflation running high, core inflation has held steady at an annualized rate of 5% over the last few months.

Conclusions

The fact that energy is responsible for a large chunk of inflation represents a unique problem—and a unique opportunity. Getting housing price growth or restaurant price growth down would require reducing aggregate demand or unlocking dozens of supply chain bottlenecks and wouldn’t show up in the data for months; reducing energy prices could immediately lower inflation and would require less coordination.

But that means rejecting counterproductive solutions. America has often banned energy commodity exports during periods of extreme shortage—and proposals are kicking around to implement similar export bans today. These policies rarely achieve their intended objectives and foster dysfunction along the way. A crude oil export ban wouldn’t achieve much beyond making trade flows more complicated and expensive—as the US remains a net importer of crude. Given the global refinery shortage a gas export ban would disturb foreign markets and could lead to retaliatory measures. A ban on LNG exports could reduce domestic utility bills—by throwing Europe under the bus and Ukraine under the tank. Windfall profits taxes could raise a bit of government revenue—but only by dramatically increasing the uncertainty that is preventing private investment today.

Using the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to write oil put options or buy crude futures contracts could actually reduce investment uncertainty while likely netting the government a tidy profit. Encouraging work from home could also provide households more flexibility in their consumption decisions. While the evidence is scant that work from home actually lowers travel or energy consumption, it at least offers workers more options in forming their travel and energy consumption decisions. Meaningfully accelerating renewable investment could allow natural gas and coal destined for electricity generation to be repurposed for other uses, lowering prices in the process.

The current nature of domestic inflation will make it extremely difficult for the Federal Reserve to ignore the rise in energy prices as they would in normal periods. Getting energy prices back on track will be critical to affording them the political space to make better decisions about the path of monetary policy.

Alas, I don’t think the Fed’s tools were designed for these problems and are unlikely to be very effective, at least for quite a while