A Global Perspective on the Car Shortage

Pandemic-Era Car Shortages are the Defining Example of Supply-Chain Driven Inflation—And Vehicle Production Issues Are Still an Ongoing Worldwide Crisis

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 21,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Car shortages have been the defining story of pandemic-era supply-chain-driven inflation and global physical capacity shortages. Extremely intricate, physically massive, and increasingly dependent on electronics, vehicles are among the most complex manufactured consumer goods—and critically, their production is highly politicized with regulations, trade barriers, and government incentives fracturing global supply chains across regional and national lines.

When the pandemic hit, vehicle assemblies briefly halted across the world—and automakers drastically reduced their production plans while bracing for a global recession. As the economy recovered quickly, global output become hamstrung by ongoing shortages of semiconductors and other electronic components as car companies struggled to re-secure critical inputs.

Now, nearly three years later, global production is slowly recovering—but remains heavily constrained by ongoing supply chain issues while the cumulative backlog of “missing production” remains extremely large. Given how essential vehicles are for basic global transportation—and how rising vehicle prices have accelerated worldwide inflation—it’s worth taking an in-depth look at today’s global car shortage.

The Global View

Right now, it’s the world’s two biggest car manufacturers that are leading the global recovery—Chinese and American vehicle production now sit marginally above pre-pandemic levels while Eurozone, Indian, and Japanese production remain about 10-20% below 2018 levels. Fluctuations in Chinese output have been driven more by COVID-related production impediments than the semiconductor shortage—and the nation saw a total collapse in passenger miles amidst ongoing lockdowns from 2020-2022, leaving them in a vastly different situation than the rest of the world. Now that COVID restrictions are being lifted and the Chinese economy is reopening, stronger demand pressure will be put on Chinese vehicle manufacturers for the foreseeable future. In the states, however, the situation is different: automakers have caught up to pre-pandemic production levels but are still dealing with large backlogs of unfulfilled orders and ongoing material shortages.

The Car Shortage in the Americas

At its lowest point in 2021, American motor vehicle assemblies had fallen more than 20% from pre-pandemic levels amidst the semiconductor shortage. Combined with lower interest rates, stimulus-driven demand, and the reallocation away from air travel and public transportation, the production shortfall led prices for used vehicles in the US to rise by an astonishing 50%. Now, used car prices have fallen back down but remain high—and wholesale market data suggests a stabilization in prices, at least over the short term.

Ongoing production shortfalls among America’s major trading partners help explain part of the puzzle—the American car market is more of a semi-integrated North American market, so prices haven’t fallen as much as expected because output isn’t as strong as American data alone suggests. Canadian car production, for example, remains just barely above half its pre-pandemic level amidst ongoing supply constraints, production switches, and retooling for electric vehicles.

Although granular data is not available at the moment, Mexican car production also looks to still be below pre-pandemic levels. Given that American real net imports of motor vehicles remain below pre-pandemic levels, the strength of American production might be partially coming from the cannibalization of production in the country’s neighbors.

Either way, the trend is clear—production may have largely recovered, but the large cumulative shortfall of output over the last three years still leaves the US with a fairly dire car shortage. Just counting US production, 4.5 million vehicles are missing that would have been on the road today in the absence of the pandemic. Real inventories of vehicles and parts are slowly increasing but remain nearly 20% below pre-pandemic levels, and nominal new orders hit an all-time high back in October. The shortage may be getting better, but it is not gone.

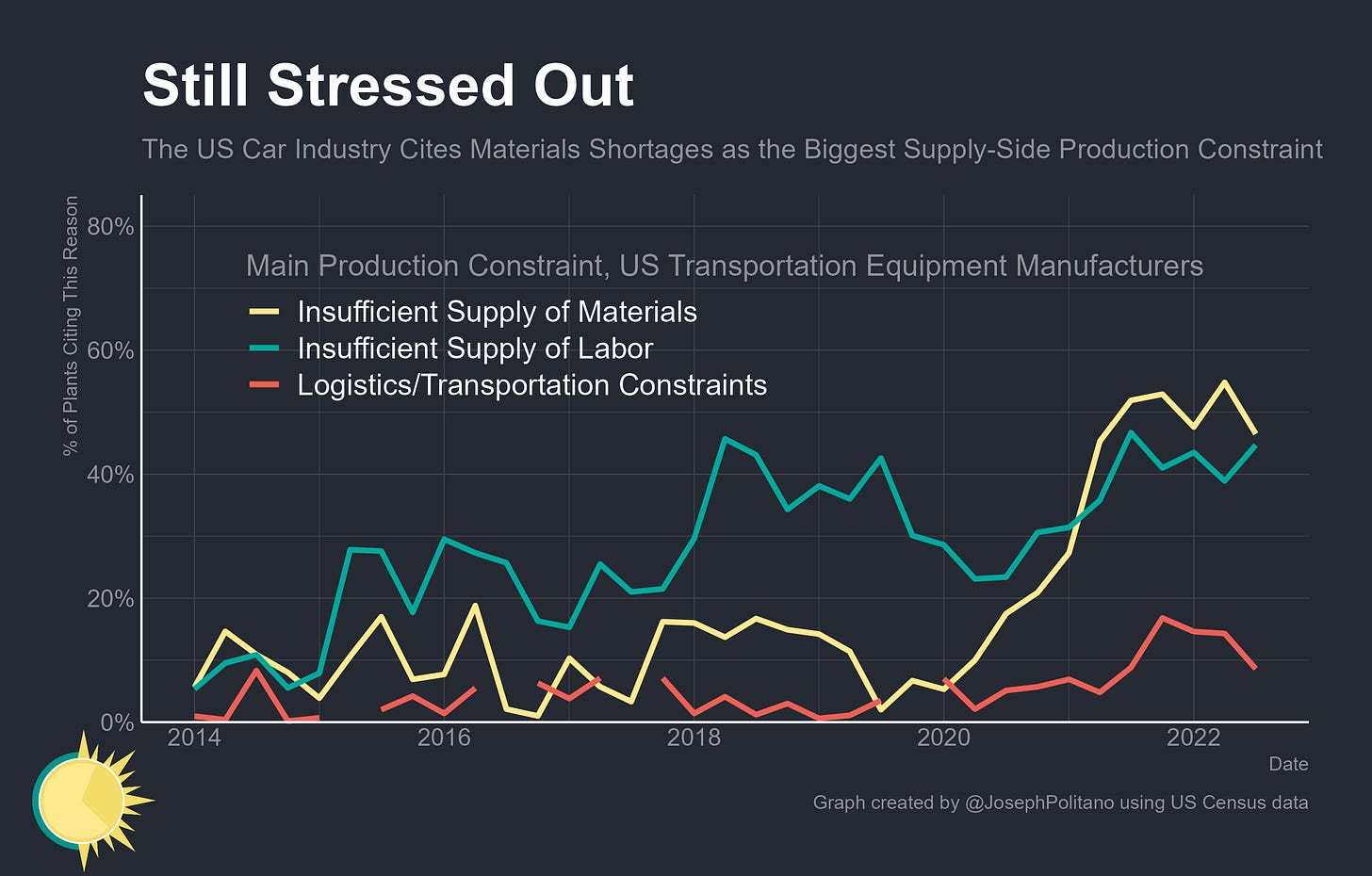

Plus, even as production has recovered American car companies are still dealing with ongoing supply-chain issues—in fact, these have barely improved since mid-2021. Record-high shares of manufacturing plants in the transportation equipment sector cited materials or logistics constraints as their main impediment to production in 2021, and those numbers have only marginally improved in Q3 2022. Especially given the slight downturn in output over the last couple of months, US automakers don’t look to be out of the woods yet.

As an aside, it’s worth noting that South America’s premier carmaker is also dealing with ongoing production issues—Brazilian car output remains nearly 25% below pre-pandemic levels, although heavy vehicles (a small share of the overall market) are picking up some of the slack. That fits into the strategy many carmakers took during the height of the semiconductor shortage: prioritizing scarce inputs for the vehicles with the biggest margins, which tend to be the biggest vehicles. In 2019, Brazil assembled about a million more vehicles than Canada—so while they do not have the same level of market access to the US, they do represent a key struggling section of the global car market.

The Car Shortage in Europe

Across the pond, European automakers are in a worse situation than their American counterparts. Hit with the double-whammy of material and energy constraints, they still have not recovered to pre-pandemic output levels and suffered a second big hit in early 2022 just after the Russian invasion.

In particular, the vaunted German car industry is struggling the most—there, vehicle output is down 25% from 2018 levels as the pre-pandemic downturn was only accelerated by COVID, the chip shortage, and the ongoing energy crisis. None of the major Eurozone nations have seen their output return to normal levels—although Turkey, the second-largest non-EU carmaker on the continent, has recovered fully. Part of that is just the long-run growth of the Turkish economy—but some of it likely represents a boost from Turkey’s unique and growing trade relationship with Russia.

The smaller EU manufacturers are also doing better than their bigger neighbors, with Poland, Czechia, and Romania notching new record highs as they continue their growth as rising manufacturing centers. The big disappointment is in the UK, whose output now sits below 60% of pre-pandemic levels.

Still, the big story is that European automakers are arguably in the worst position of any automakers on the planet, excluding their Russian counterparts. More than three-quarters of Euro Area motor vehicle manufacturers are unable to ramp up production thanks to materials shortages—whether that be semiconductors, metal, parts, or energy—and that number ended the year only slightly below the historic high of 80% reached just as the Russians invaded Ukraine. That’s part of the reason secondhand car prices are up 12% in the Eurozone even as they are falling in the United States—and it is the challenge for European automakers going forward.

The Car Shortage in Asia

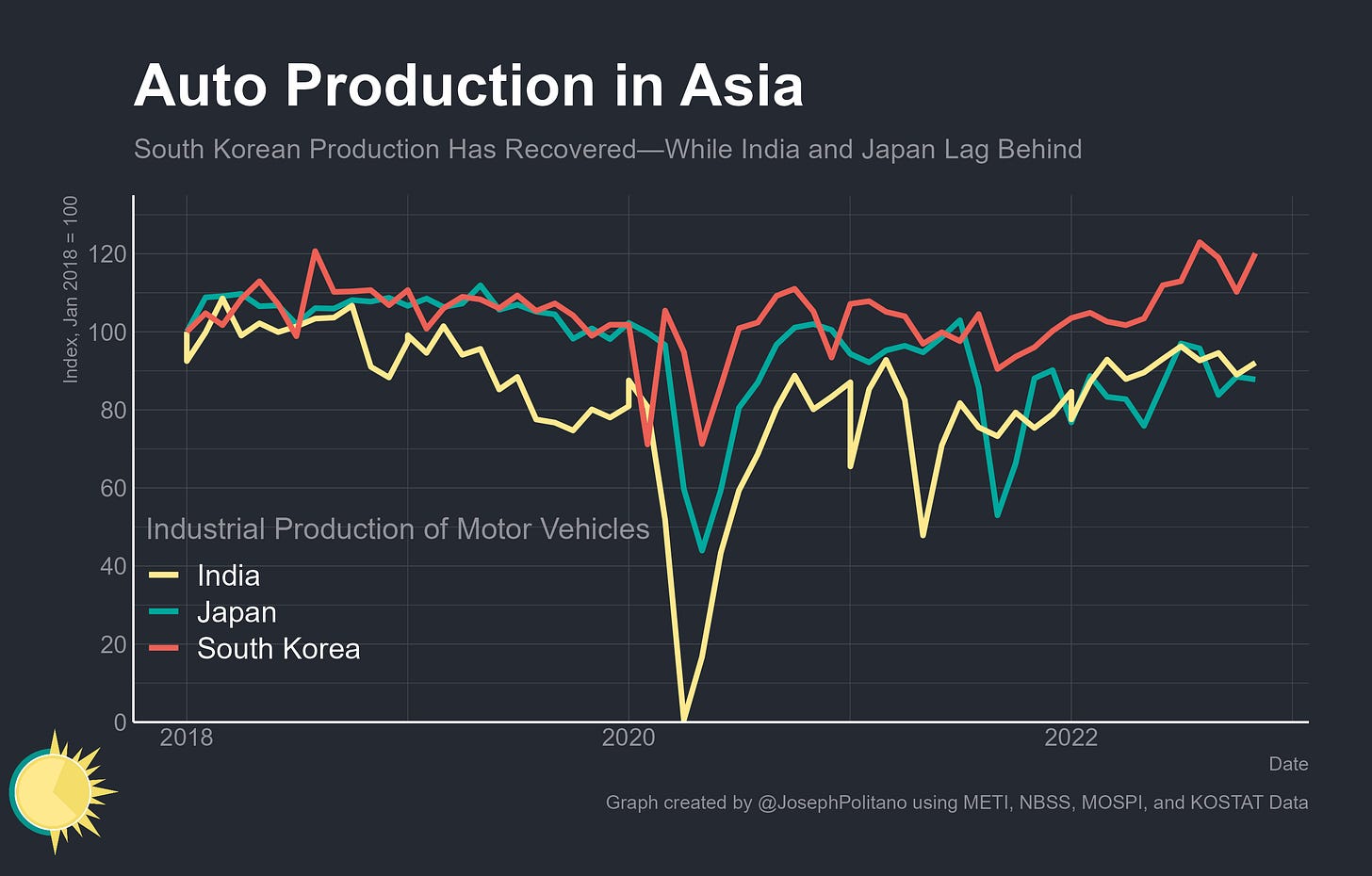

If European automakers are the hardest hit by supply-chain crunches, Asian automakers have arguably been the least hit. Thanks to better containment of COVID-19, stronger supply chains, and a better job at sourcing semiconductors, Asian automakers returned to pre-pandemic levels the quickest and stayed there the longest. South Korea’s results in particular are so good you could almost forget there was a pandemic, with output now 20% above January 2020 levels. India has also posted a solid recovery, with output currently exceeding pre-pandemic levels. Japan managed to dodge the worst effects of chip shortages throughout early 2021—though they were hit badly later in the year and remain about 10% below normal levels.

Japan gives one of the most detailed breakdowns of auto production data, giving us a better glimpse at the item-by-item movements within the car shortage. Buses got hit the hardest by the initial wave of COVID and have still not recovered to pre-pandemic levels—though it was passenger cars that were hit worst by the COVID outbreaks and chips shortages of 2021. Motorcycles, surprisingly, were the first to recover and have been the strongest sector in Japan in recent months.

Chinese production, on the other hand, has been highly volatile, especially as intermittent lockdowns rolled the country. Truck production was the obvious winner in the early pandemic: even as people were locked down, freight volumes remained extremely high and so production was recentered towards industrial vehicles. Now, the opposite is occurring: truck production is lagging even as passenger vehicle production surges. Official Producer Price Index data suggests that car prices moderately declined throughout the pandemic and that only certain subsectors (refitted and low-speed vehicles) experienced any substantial increase. Still, by virtue of being the world’s largest source of motor vehicles, the disruptions to Chinese output still likely remain the largest source of “missing” vehicles, and it remains to be seen how those shortages will mix with a reopening Chinese economy.

Conclusions

If there is any lesson to be learned from the car shortage it’s that supply-chain hiccups can be anything but transitory—the fact that global car production remains hamstrung three years on from the initial start of the pandemic and two years on from the first shock to car prices should show how short-term crises can have long-term effects. It’s also a good lesson that supply-chain isolation isn’t always supply-chain durability: being well-connected to Canadian and Mexican car industries has been a boon for the US, and being able to pull durable manufactured goods from abroad has helped the EU weather the energy shortage. More than anything, the car shortage and the chip shortage have been emblematic of the increasing complexity and interconnectedness necessary for modern, global manufacturing—something that will likely only become more true as the world transitions to electric vehicles.

Very interesting article, I was really anxious waiting for your views on this market. When one looks at a car as a product where so many technologies are integrated it becomes clear that it will take a long time to go back to normal. Hard to understand how higher interest rates might help to alleviate these problems. Regards

Hey Joe,

Lots of great insights, thanks! Some thoughts:

- Your point in China and the US being the world's two biggest car manufacturers is true if you take the eurozone as one entity. If you take the EU, than that's the second largest, ahead of the US.

- About European automakers more specifically: Their margins are actually at record highs. They are hit “hardest” by the supply-chain crunch but discovered that this scarcity is actually quite beneficial to their bottom line, especially in customer segments they are in. Hence the effect on GDP is still muted. European automakers produce fewer cars but make record revenues regardless.

Would be curious to hear your thoughts about how thag compares to American and Asian manufacturers.

Best,

Ben