A Historic Labor Market Recovery

American Employment Rates Have Fully Recovered From the Pandemic—But We Shouldn't Stop Here

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 25,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

After the 1990 Recession, it took more than 6 years for America’s labor market to fully recover. After the 2001 recession, America’s labor market never recovered—the Global Financial Crisis interrupted a weak 5-year-long expansion. After the Great Recession, it took twelve long years for the labor market to recover, permanently damaging America’s productive capacity, health, and welfare.

Today, three short years after the first spike in unemployment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, American prime-age employment rates have fully recovered and even exceeded 2020 levels. It marks one of the most rapid, comprehensive, and broad-based labor market recoveries in US history, with the unemployment rate dropping from nearly 15% in April 2020 to near-historic-lows of 3.5% today. Across nearly every relevant age and demographic group, as many or more people are working today than in 2019.

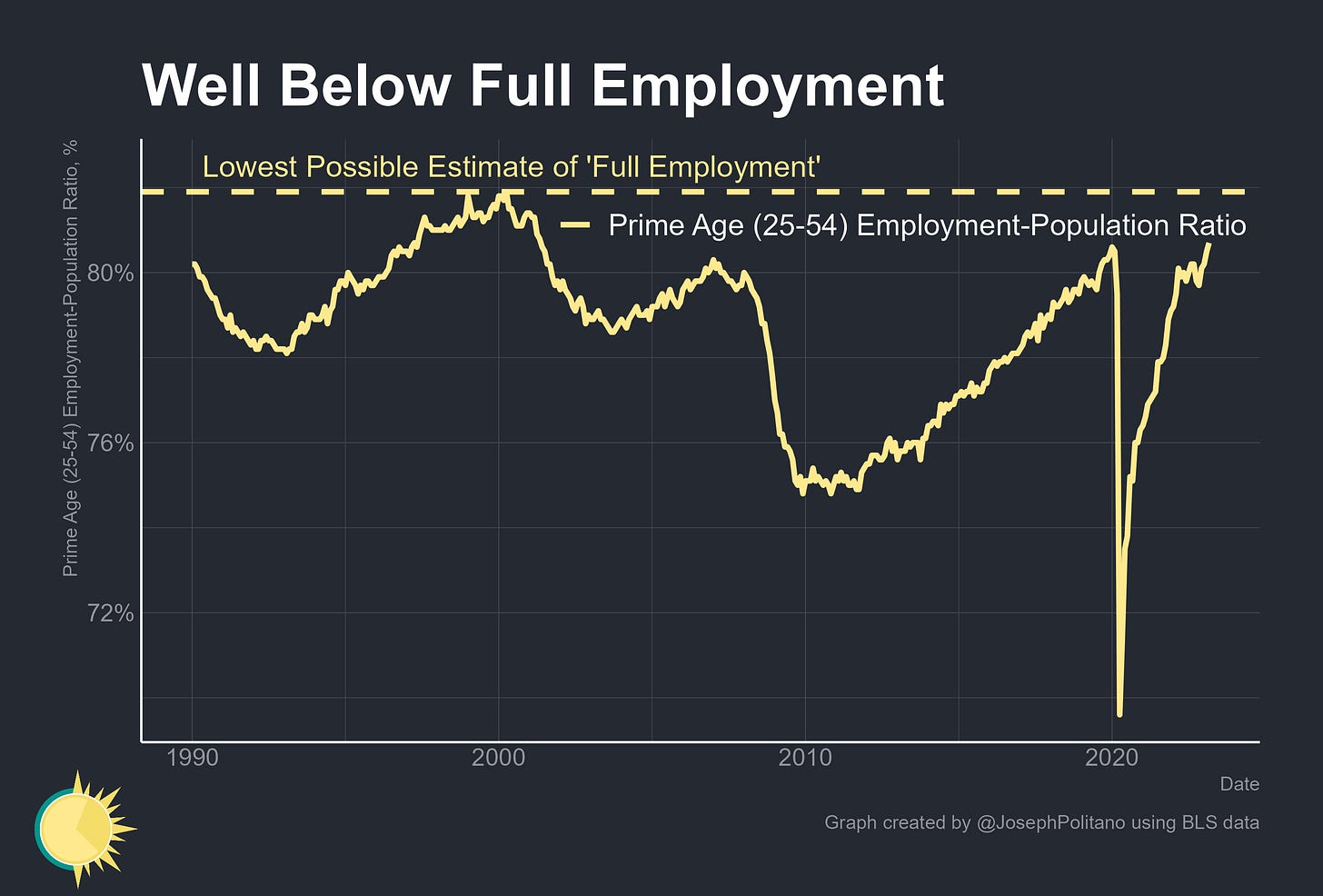

However, it’s worth remembering that since the early 2000s American employment has been on a downward trend—thanks in large part to the weak recoveries in 2001 and 2008. The lasting damage is so bad that today, in 2023, 1.5 million more prime-age Americans would need to get a job just for their employment rates to match the record highs set in the year 2000—in other words, America’s labor market is still nowhere near what a comprehensive definition of full employment would entail.

Plus, America’s employment rates have fallen well behind those in peer countries over the last two decades, and during the pandemic that gap has only increased. Japan, Germany, Canada, Australia, and more saw smaller employment shocks from the initial effects of COVID and more rapid labor market expansions than the US over the last three years. Today America’s fragile employment gains are at risk as the chances of a recession loom large—although wage growth and inflation have thus far slowed amidst job gains, the Federal Reserve believes stopping excess inflation will require a large increase in the unemployment rate this year. But today’s historic labor market recovery is worth celebrating—and defending.

A Broad-Based Recovery

Almost all industries have now recovered to pre-pandemic employment levels, and total payrolls now sit more than three million above the 2020 peak. The only sectors with slightly smaller workforces are Leisure & Hospitality and Government (which includes public schools), both of which have struggled to retain workers given the surge in better-paying jobs elsewhere. Indeed, high-paying industries like professional & business services have boomed since the start of the pandemic, as have industries like Trade, Transportation & Utilities amidst strong demand for consumer goods.

The recovery has been broad-based across age groups too—teenagers, young adults, prime-age workers, and 55-69 year olds all are employed at effectively equal or higher rates than they were before the pandemic. The only age group where employment rates remain depressed is the 70+ category, a group that composes an extremely small share of the workforce to begin with and (quite reasonably) was more likely to retire amidst the pandemic.

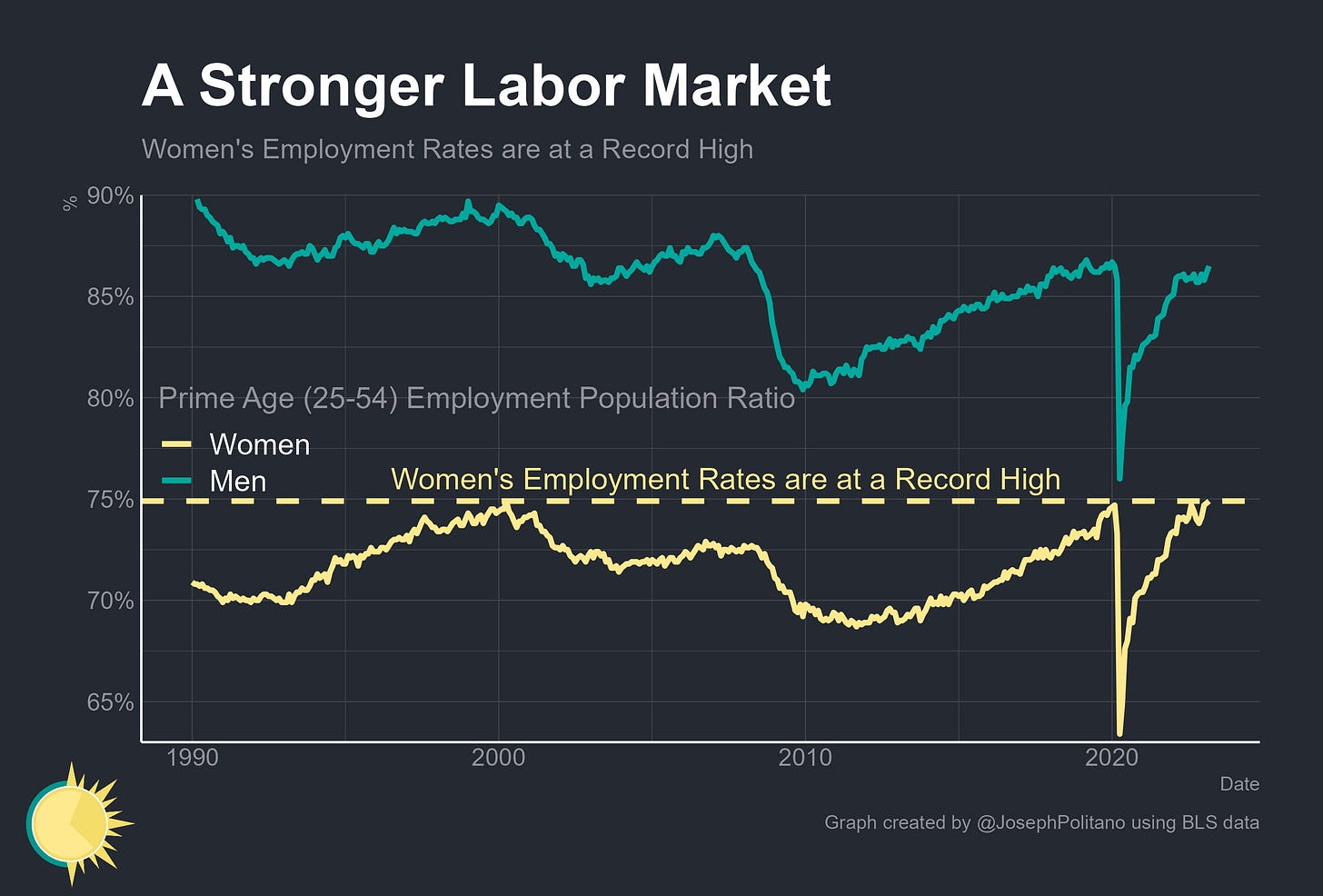

The economic recovery has also driven significant job gains for groups with structural, historic employment disadvantages in the US—the kind of marginal workers who tend to benefit only when the labor market is at its strongest. As of March, prime-age employment rates for American Women have tied the all-time record high previously set in early 2000—a far cry from the 35-year lows seen in 2020 that prompted fears the pandemic would cause lasting structural damage to women’s economic opportunities.

Black prime-age employment rates have also risen to a record high this year, the Black-White prime-age employment gap has fallen to a record low, and the Black unemployment rate, at 5%, is now at the lowest level in American history. Prime-age employment rates for Asian workers are also at record highs, with Asian women in particular seeing a massive 5.6% increase in employment rates between March 2019 and March 2023. Unemployment rates for Hispanic/Latino Americans were at a record low of 3.9% in September and, though they’ve risen since then, remain just a bit above 2019 levels.

The Dual Mandate

Still, all of those gains are in a precarious position. The Federal Reserve sees inflation as too high, and at their last meeting the median member of their rate-setting committee expected the unemployment rate would need to rise to 4.5% by the end of 2023 (a full 1% increase over the next nine months) in order to get inflation down. A jump in unemployment that rapid can only be consistent with a recession—so either the Fed is wrong that unemployment must rise that fast to ensure price stability or today’s historic employment recovery will end in another downturn.

So far, the signs of abating inflationary pressure in the labor market have been reasonably encouraging—even as employment has continued increasing, wage growth has continued decelerating towards the high end of the pre-pandemic norm. Average hourly earnings for private-sector workers rose by 4.2% over the last year, the lowest amount since mid-2021, and wage increases over the last quarter were consistent with a fairly normal 3.75% annual growth rate.

That recent labor market deceleration has also affected gross labor income, the aggregate nominal wage income of all workers in the US. Over the last year, gross labor income grew 6.5%—the lowest annual growth rate recorded since early 2021 and within reach of the 5% average growth rates that the US saw throughout the 2010s. Some deceleration here is still needed—the quarterly increase over the last three months was nearly 6.5% annualized, an amount more consistent with 3.5-4% inflation than the Fed’s target of 2%—but recent data still represents a substantial drop from the 10% annualized growth seen at the beginning of last year.

The rate of workers quitting their job—an important indicator of labor market tightness given that most quits represent workers taking on other higher-paying jobs—has also fallen significantly over the last year. Firms expect labor to have an outsized weight on cost increases over the next year, but those expected labor cost pressures have fallen far from their peaks in mid-2022. In the non-housing services industry, where the Federal Reserve believes a strong labor market is most likely to pass through to inflation, annualized wage growth has continued falling and now sits at 4.5% for the most recent quarter. Across labor market indicators, inflationary pressures are fading even as employment increases—though more improvement is necessary before inflation will return to the Fed’s 2% target.

Conclusions

The Federal Reserve has a dual mandate—to keep inflation on target and maximize employment. Over the last couple of years, concern has rightfully focused on the inflation side of the mandate—price growth, nominal spending, and nominal incomes were all far too high to be unworried about inflation. However, the Fed has already taken historically strong actions to control inflation, and those actions have had much their desired effect—headline and core inflation has fallen, nominal spending growth has declined, market-based inflation expectations were brought back to a normal range, and gross labor income growth came down from its modern record highs.

There’s still work to be done to bring inflation under control, and it will likely remain uncomfortably high for most of this year in the absence of a recession. But that discomfort will not be the same as the crisis that price increases were last year, and the Fed has often made the mistake of focusing too much on the inflation side of the dual mandate at critical economic turning points. For today’s historic labor market recovery to continue, and for American employment rates to one day catch up with our peer nations, the Fed will have to start worrying about the employment side of their mandate once again.

Hard-to know factoids, graphs and data are just wonderful Joseph and thank you very much for your research. I am hopeful that we can get thru this without too much recessionary pain!

I’m curious where, in normal working ages, the difference between the US and our peers lies. Is it across the board? Is it in the earlier years, perhaps reflecting longer stays in college and greater childbirth and child-rearing? I’d be surprised if it was as the end, given that our peers typically have earlier, not later, retirement ages. Though perhaps the combination of disability and early-retirement programs could do that. If this was addressed in the piece, I missed it, so apologies in that case!