A Holiday Dive Into Food and Goods Inflation

What Thanksgiving, Black Friday, and Christmas Means for the Economy

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 19,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

The holiday season is a critical time for the US economy—retailers add on half a million new workers and retail sales climb nearly 15% from October to December. This year, amidst high inflation, rising interest rates, and slowing real growth, the holiday season has taken on renewed importance.

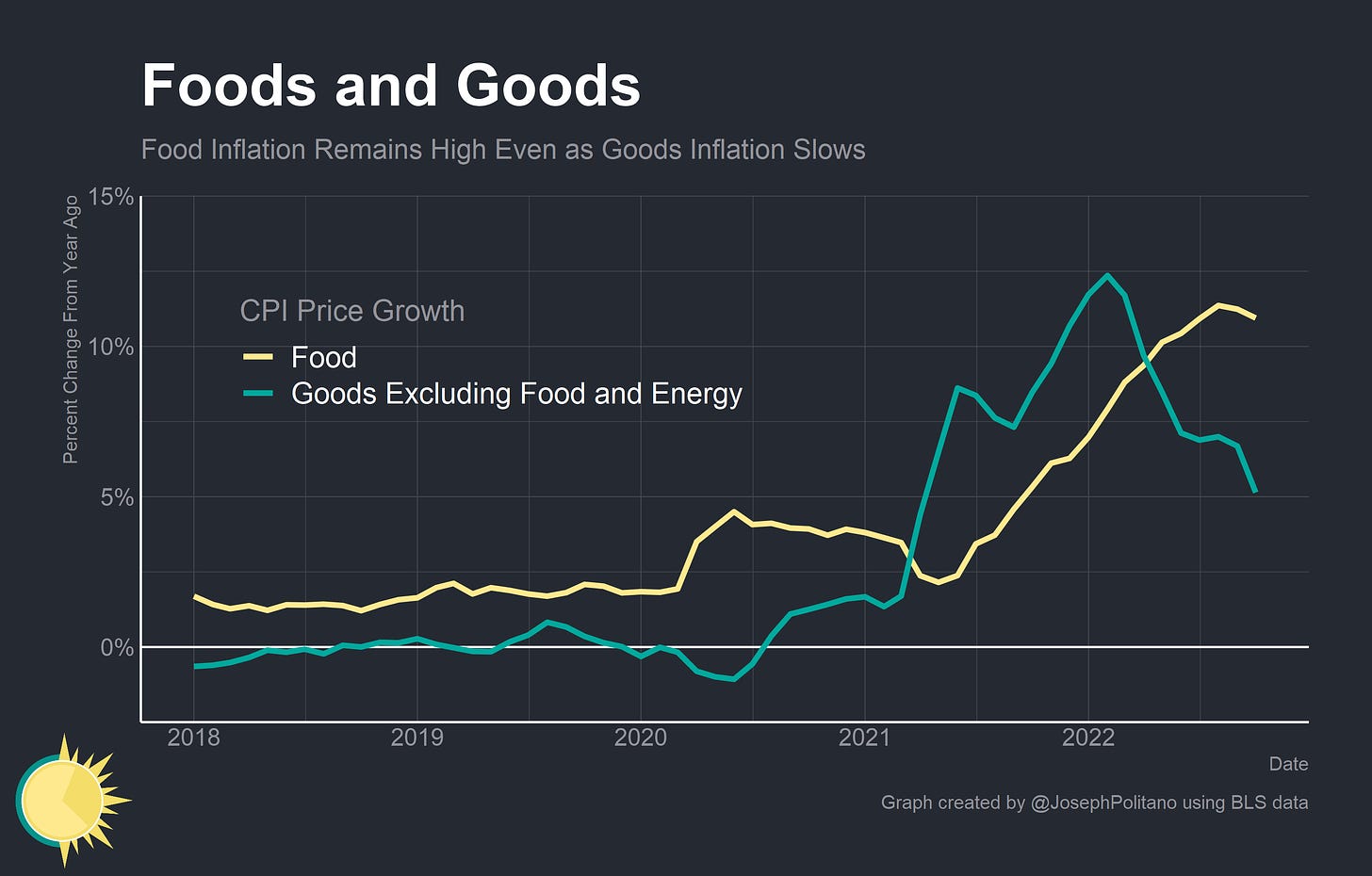

This is especially true as two different components of volatile inflation—food and goods—start moving in two different directions. Global food supply has been significantly weakened by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as Ukraine itself is a key grain and crop exporter and Russian natural gas provides critical inputs for nitrogenous fertilizers. Alongside a widespread outbreak of avian flu and other supply-side issues, annual food price growth has surged to nearly 11%. Meanwhile, price growth in durable goods is decelerating as improvements in key global manufacturing supply chains mix with improvements in retail inventories and weaknesses in consumer confidence. Holiday cooking and gift-giving will influence, and be influenced by, these shifting price dynamics.

Takeout for Thanksgiving

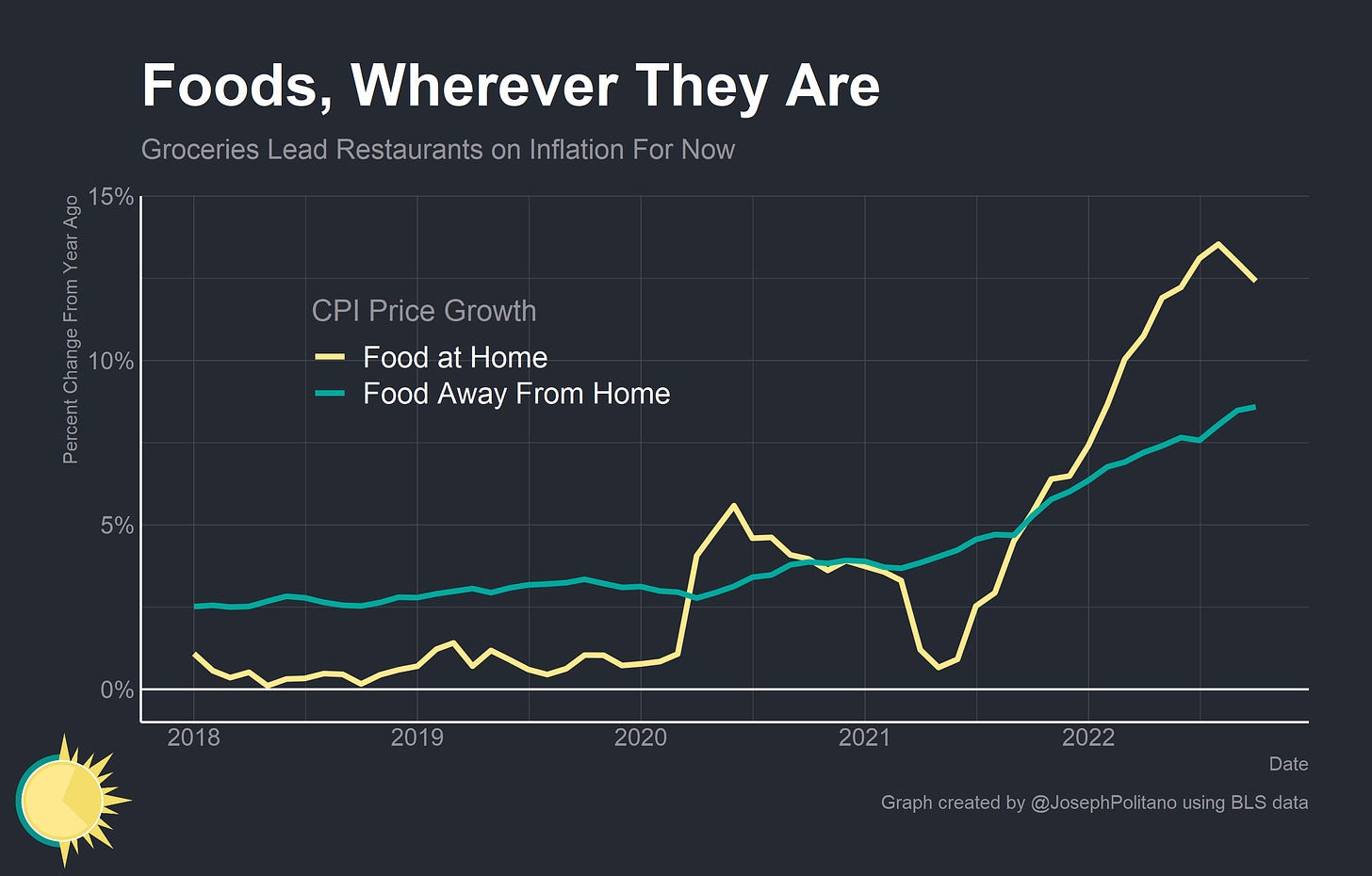

Food inflation dynamics have been particularly volatile throughout the pandemic—at the onset of COVID in 2020, the mass shift away from restaurants and towards grocery stores spurred an instant acceleration in prices for food at home. As restaurants and bars began to reopen, prices for food away from home began accelerating again—but today, grocery price inflation has exceeded 12% and again overtaken restaurant inflation in a complete reversal of the pre-COVID norm.

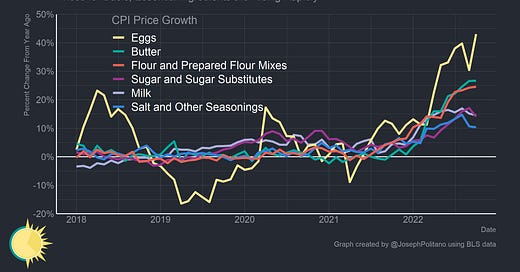

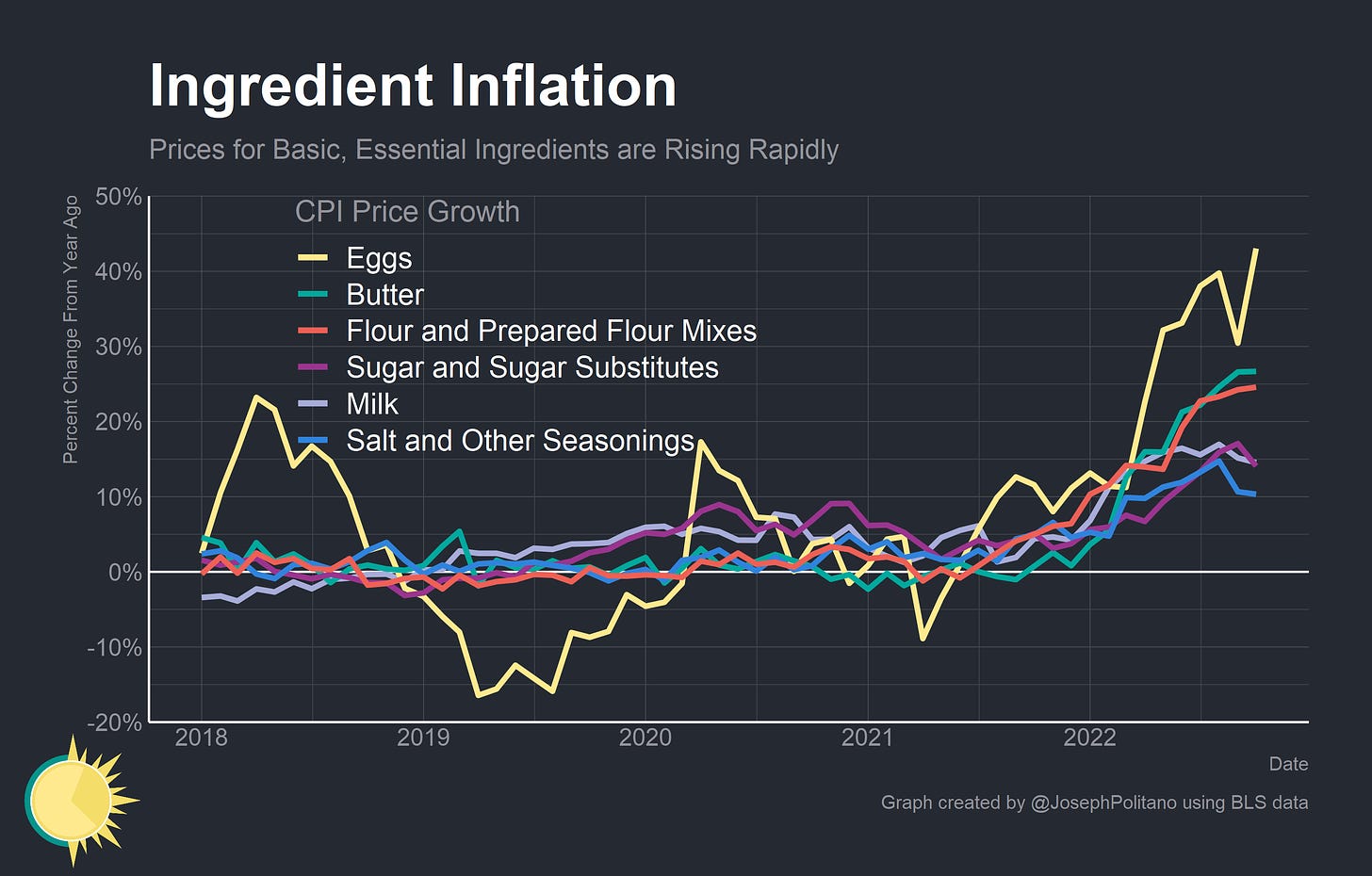

Prices for many key kitchen ingredients—eggs, butter, flour, sugar, milk, and salt—have all increased by a tremendous amount over the past year. Egg prices in particular are up 43% over the past year—the fastest pace of price growth since the mid-1980s—as the spread of avian flu takes a bite out of domestic egg production. Butter and milk prices are rising alongside broader supply issues in the dairy industry—milk production was below 2021 levels for most of this year, and butter inventories are being drawn down rapidly.

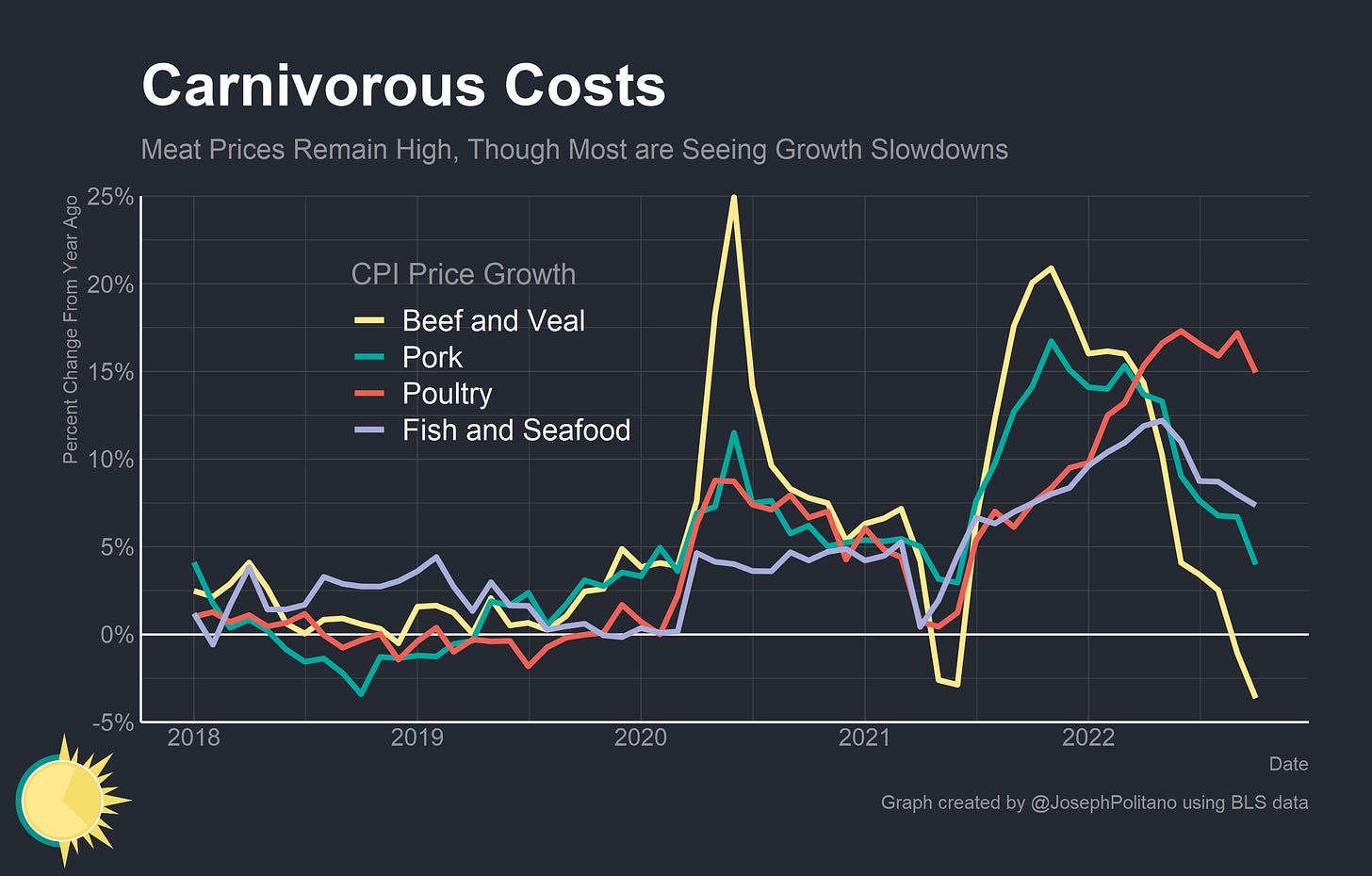

Poultry prices are also unsurprisingly adversely affected by the avian flu—if your Thanksgiving turkey was more expensive than usual, you may have that partially to blame. Outside of poultry meat prices are stabilizing (and even declining for beef), but still remain well above pre-pandemic levels.

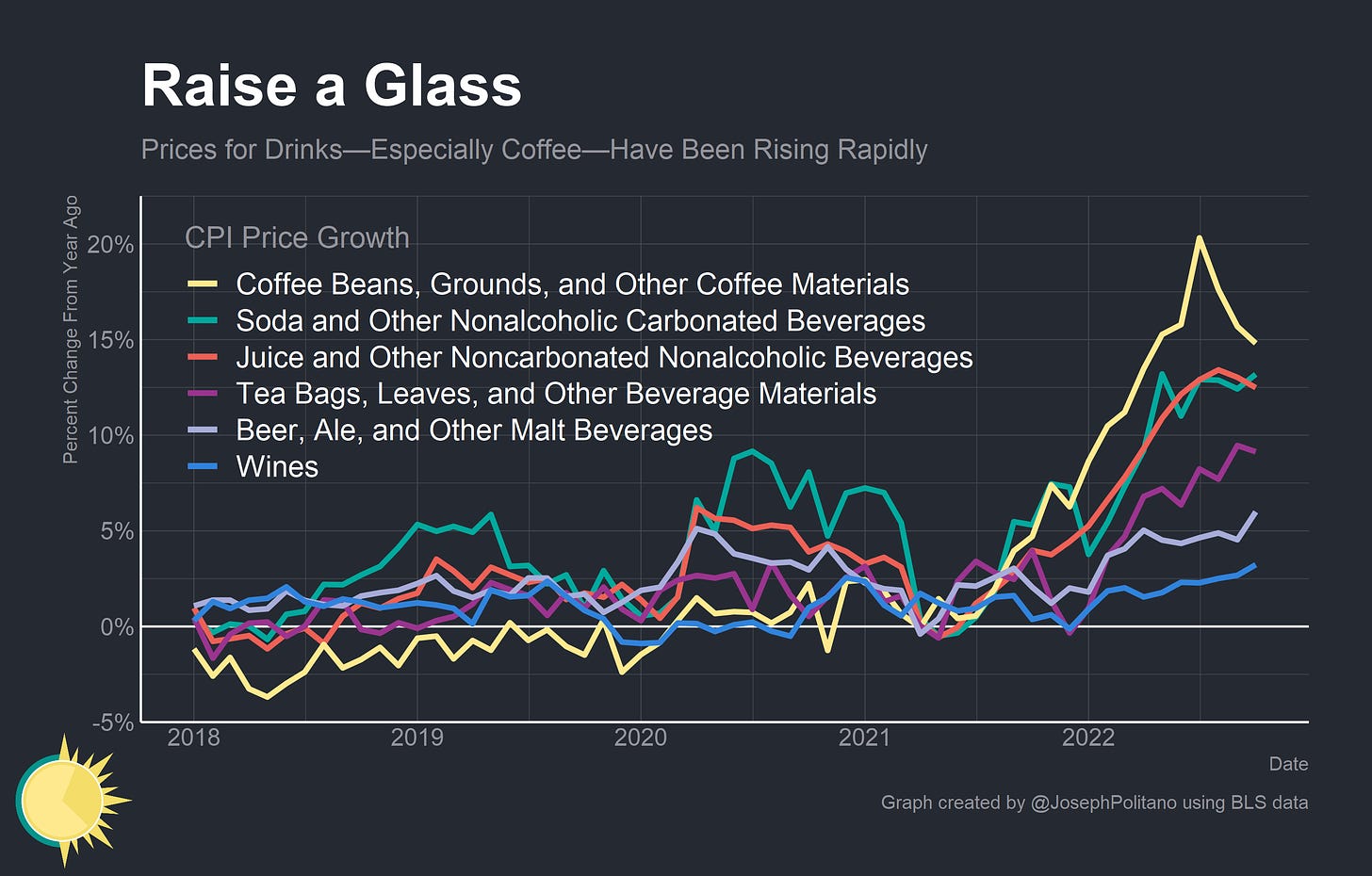

Prices for drinks have risen significantly as well—coffee prices in particular have increased more than 20% since mid-2021 alone. The good news, though, is that coffee futures prices have given up about half their gains thanks in part to better-than-expected weather in Brazil and consumer prices have stabilized over the last three months. Carbonated and noncarbonated beverages have also increased in price by about 12.5% over the past year. The only relief is in alcohol, where price growth for beers and wines has been comparatively muted.

The pandemic and food inflation have also accelerated trends from before COVID—2019 was the first year in US history where Americans spent more in restaurants and bars than at grocery and liquor stores. The initial shock of the pandemic dropped restaurant spending by more than 50%, but since then American spending on eating out has more than fully recovered. Retail sales at food service and drinking places have risen 50% above early 2018 levels and now comfortably exceed spending at grocery stores. Strong spending growth and rising real consumption have also undoubtedly contributed to some of the elevated food inflation that the US has experienced over the last year.

Good to Go (Shopping)

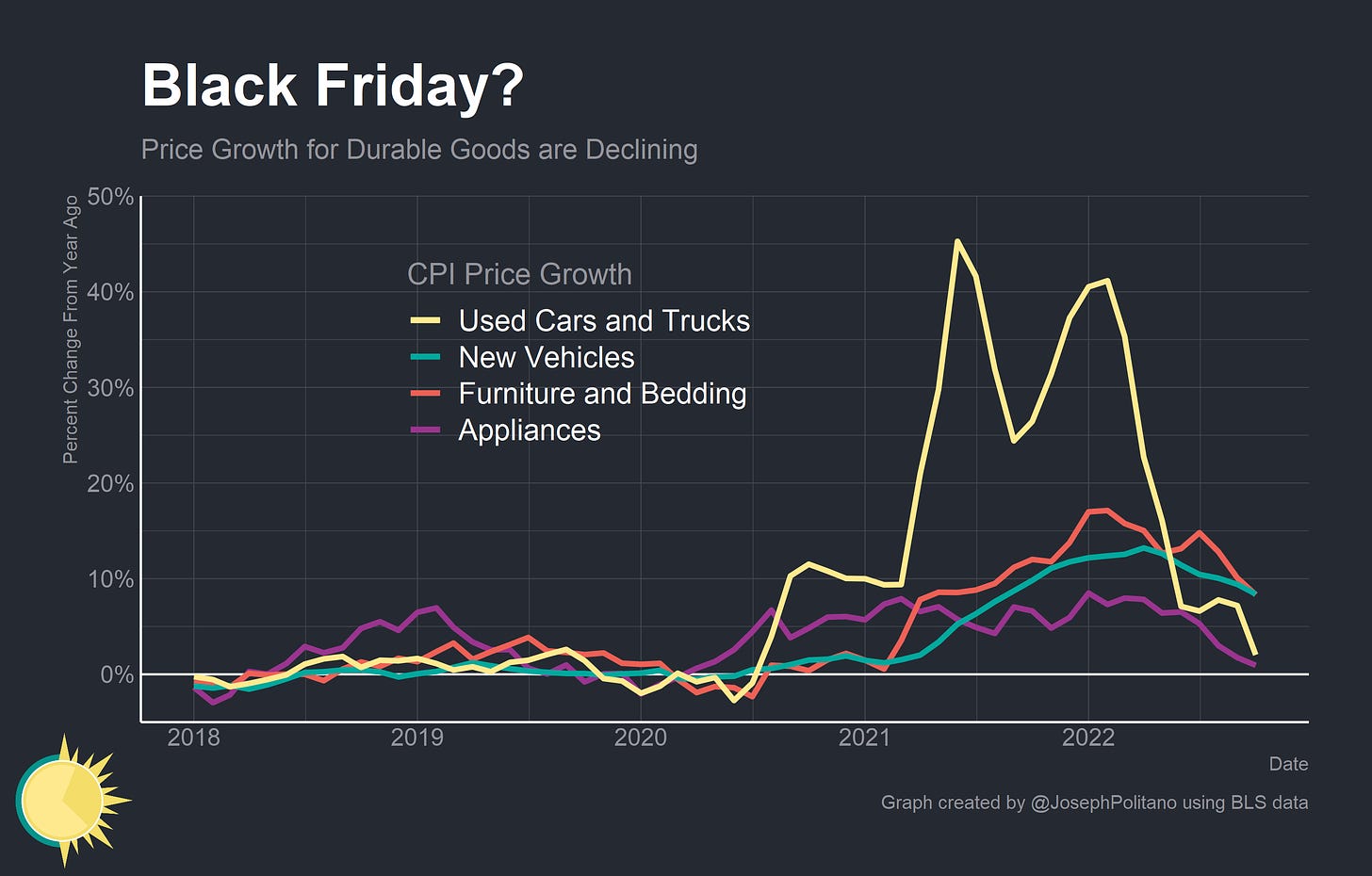

On the flip side, price growth in many key durable goods sectors has declined rapidly over the last year. Appliances like laundry machines and dishwashers have essentially seen no price growth over the last twelve months, and used cars and trucks have slowly started to decline in price after massive increases in 2020/2021. Price growth for furniture is cooling alongside drops in housing construction, and even new car prices are cooling a bit as domestic motor vehicle production picks up.

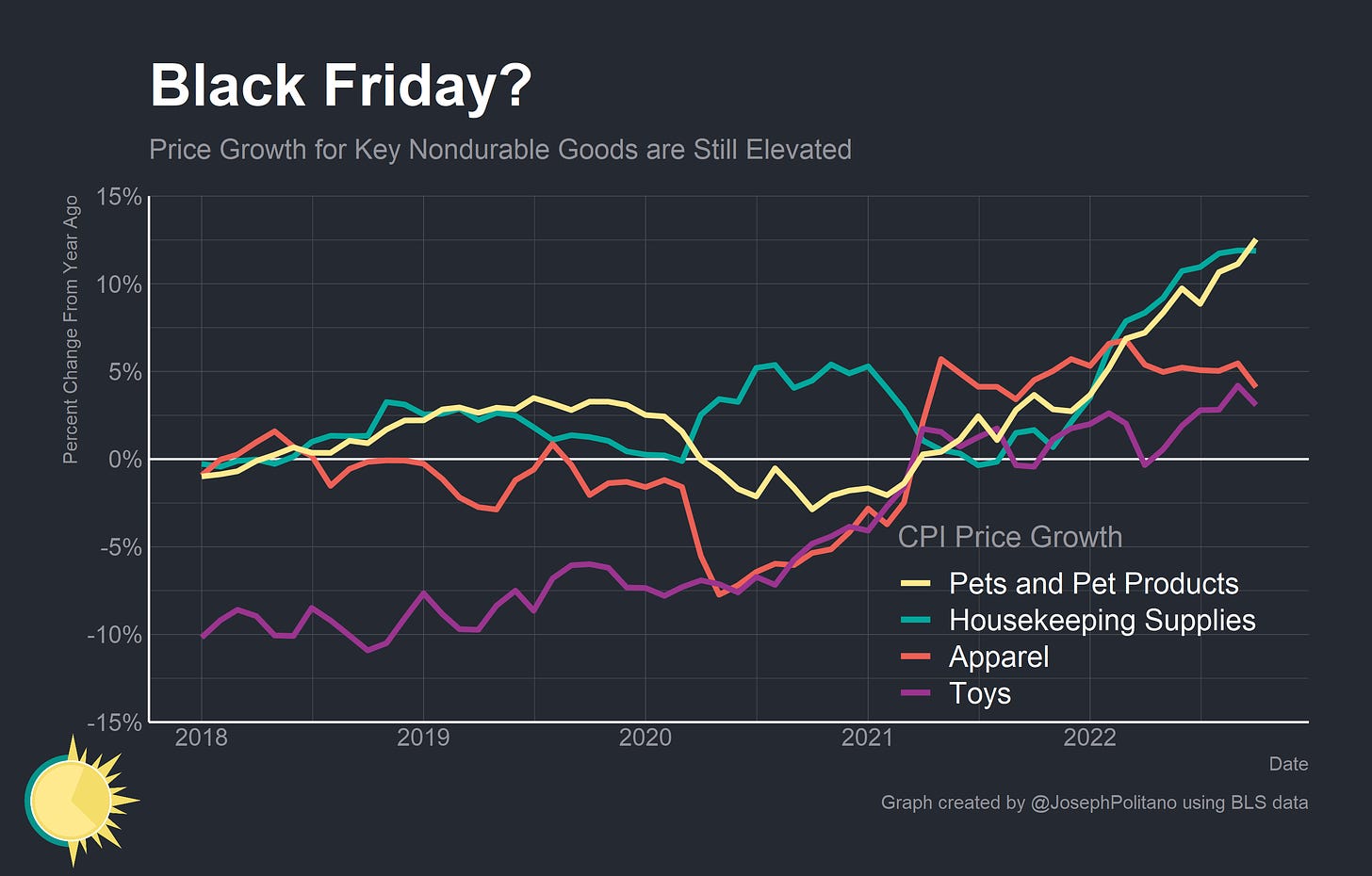

Nondurable goods prices have mostly been moving in the opposite way, however. Prices for pets and pet products have risen more than 12% over the last year, just a bit more than housekeeping supplies. Apparel prices are also up nearly 5%, with women’s clothing rising particularly fast. These price increases may not sound like much compared to other items, but core nondurable goods as a class generally do not increase in price at all—none of these items increased in price much during the entirety of the 2010s. Nowhere is the shift starker than in toys—after 20 years of straight price declines Christmas presents got more expensive in 2021, and this year is on pace to see the fastest rise in toy prices in decades.

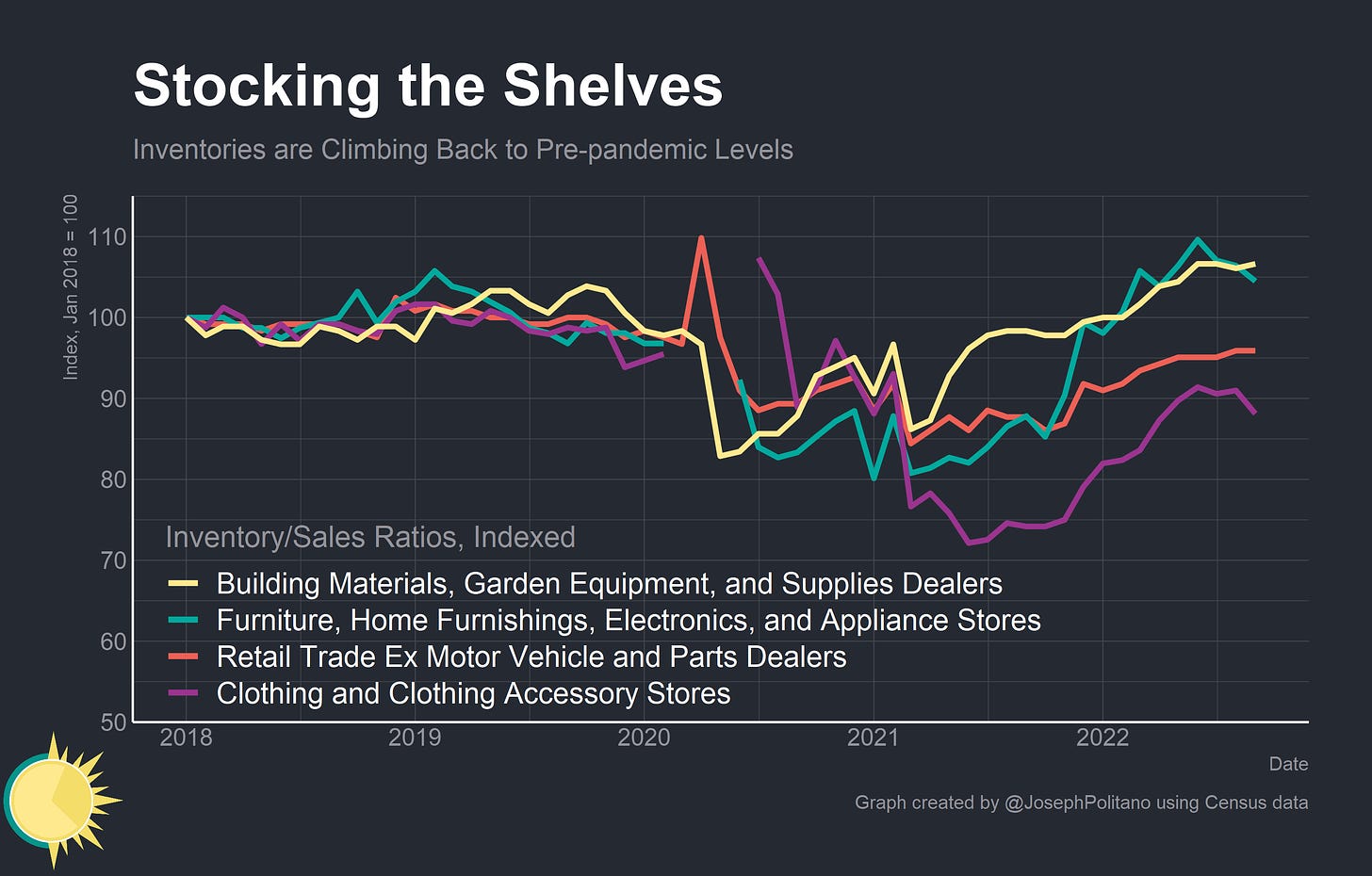

Some good news is that abating supply chain issues and improving inventories should provide a headwind to goods prices going forward. Excluding motor vehicle and parts dealers, retail inventory/sales ratios have climbed back to 95% of pre-pandemic levels. Retailers in many building, durable goods, and electronics sectors have already seen a more-than-full recovery—which might contribute to better Black Friday deals this year.

Conclusions

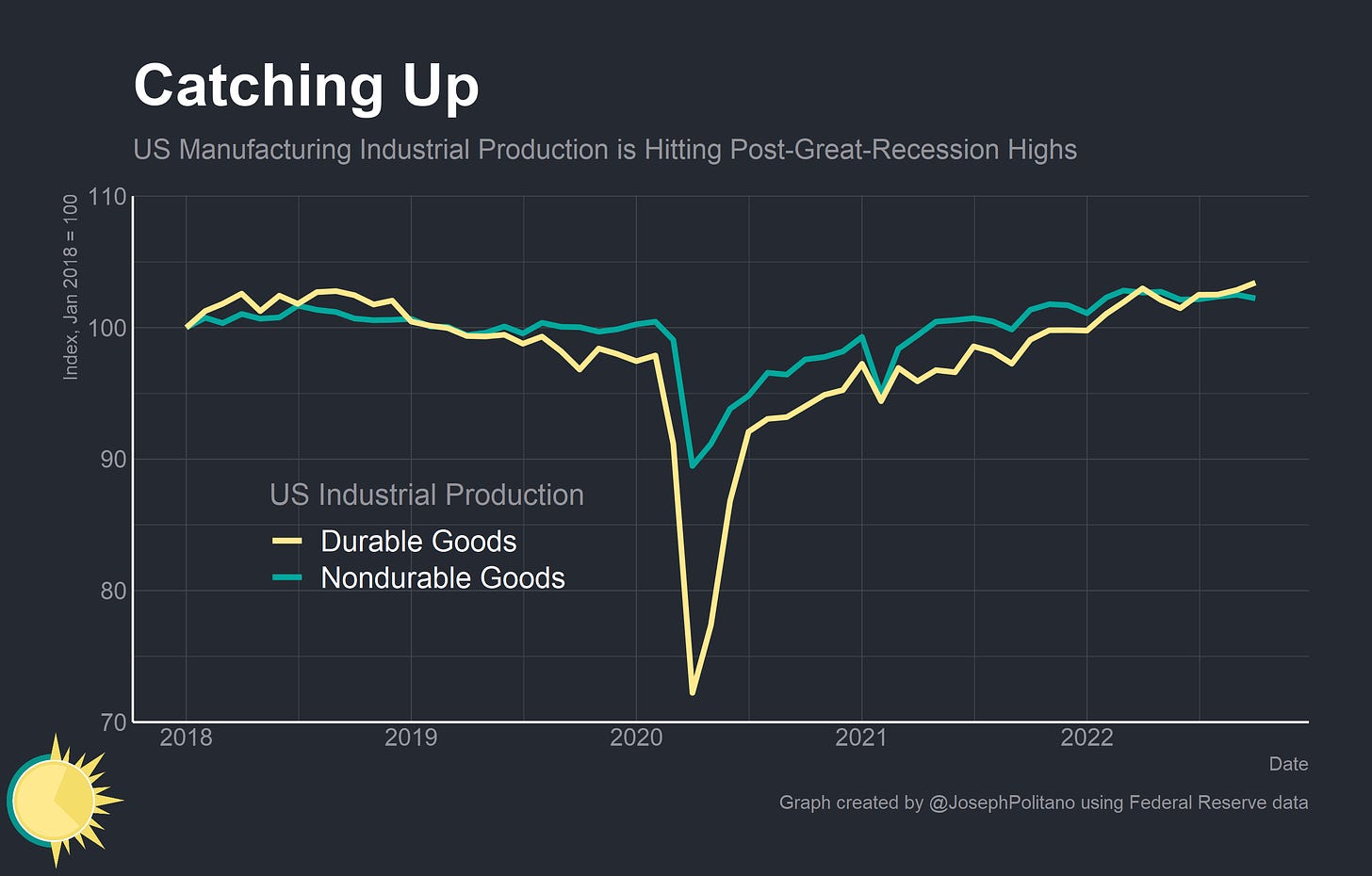

Meanwhile, US manufacturing output continues to reach new highs as supply works to bridge the gap with demand. It’s a reminder that this Holiday season contains implications for more than just inflation—employment in trucking and warehousing is stagnating or falling, the Blue Chip consensus expects weak GDP numbers in Q4, and cold weather forecasts are pushing natural gas prices back up. So, for the sake of the economy, maybe consider rooting against a white Christmas.

I would live to hear your opinions about this:

There is no physical or economic reason why human resourcefulness and enterprise cannot forever continue to respond to impending shortages and existing problems with new expedients that, after an adjustment period, leave us better off than before the problem arose.… Adding more people will cause [short‐run] problems, but at the same time there will be more people to solve these problems and leave us with the bonus of lower costs and less scarcity in the long run.… The ultimate resource is people—skilled, spirited, and hopeful people who will exert their wills and imaginations for their own benefit, and so, inevitably, for the benefit of us all

The Earth’s atoms may be fixed, but the possible combinations of those atoms are infinite. What matters, then, is not the physical limits of our planet, but human freedom to experiment and reimagine the use of resources that we have.

https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/simon-abundance-index-new-way-measure-availability-resources

Thanks for a terrific overview of our complex inflation issues