A Softer Landing on a Longer Runway?

Real Growth is Positive, but Weak—While Inflation is Slowly Decelerating. Can the US Actually Avoid a Recession?

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 28,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

America’s economy has slowed down significantly since the Federal Reserve began raising rates in early 2022—real growth has fallen, led by a decline in fixed investment, and nominal spending growth has dropped significantly. Yet we are still far from an official recession—of the six indicators the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Recession Dating Committee looks at before declaring an official recession, only two (Industrial Production and Real Retail-Wholesale Sales) remain below their prior peak levels. Meanwhile, inflation and nominal growth have been trending downward for several months now. It’s part of the reason that Fed officials are sounding a touch optimistic, despite tighter financial conditions in the wake of the recent banking crisis. The Fed no longer believes “some additional policy firming” will necessarily be required, though it is leaving the door partially open to further rate hikes if economic data comes in strong. “The case of avoiding a recession is, in my view, more likely than that of having a recession,” said Jerome Powell, in contrast with recent Fed forecasts which have expected a rapid, recessionary increase in the unemployment rate through 2023.

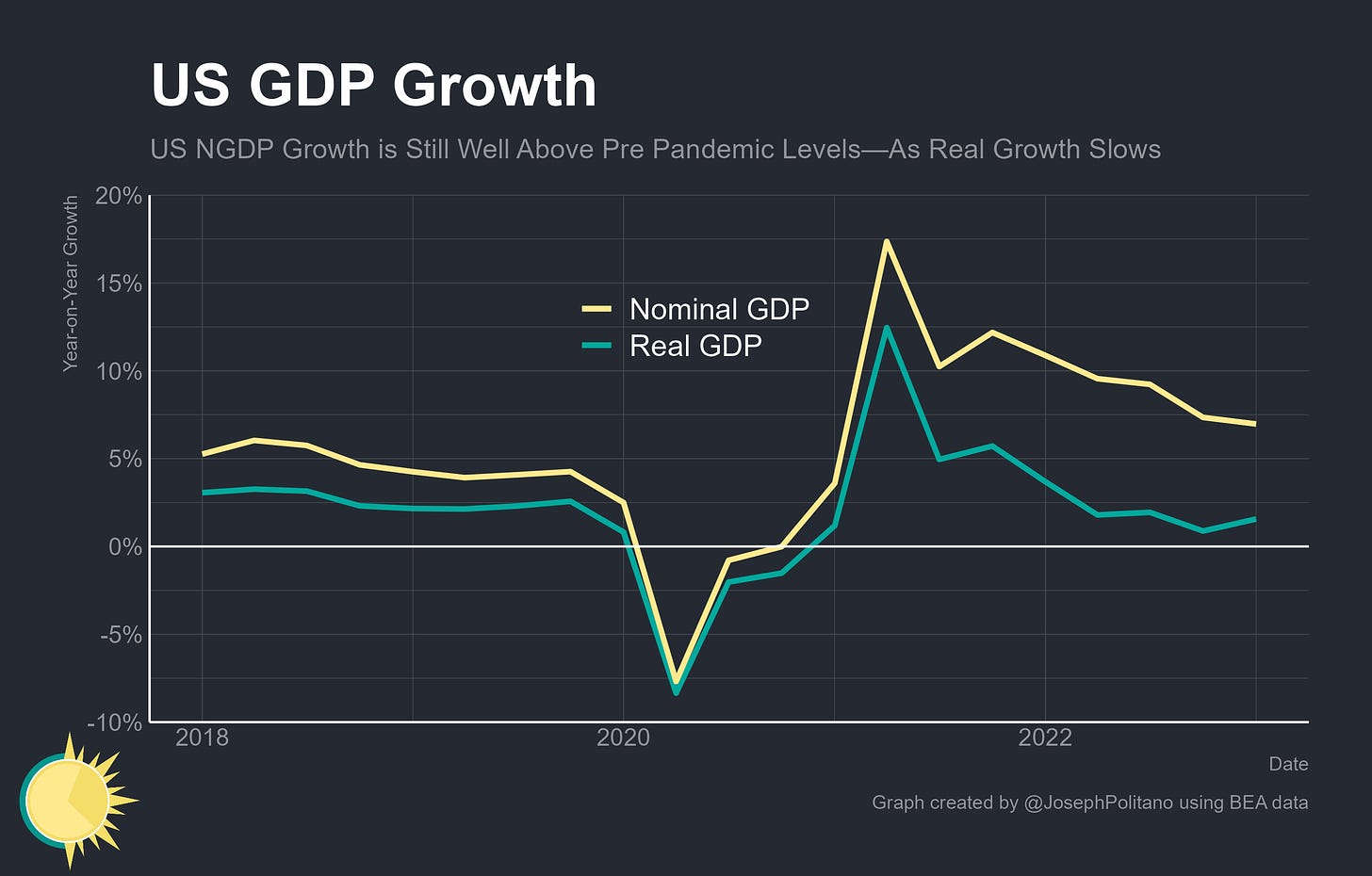

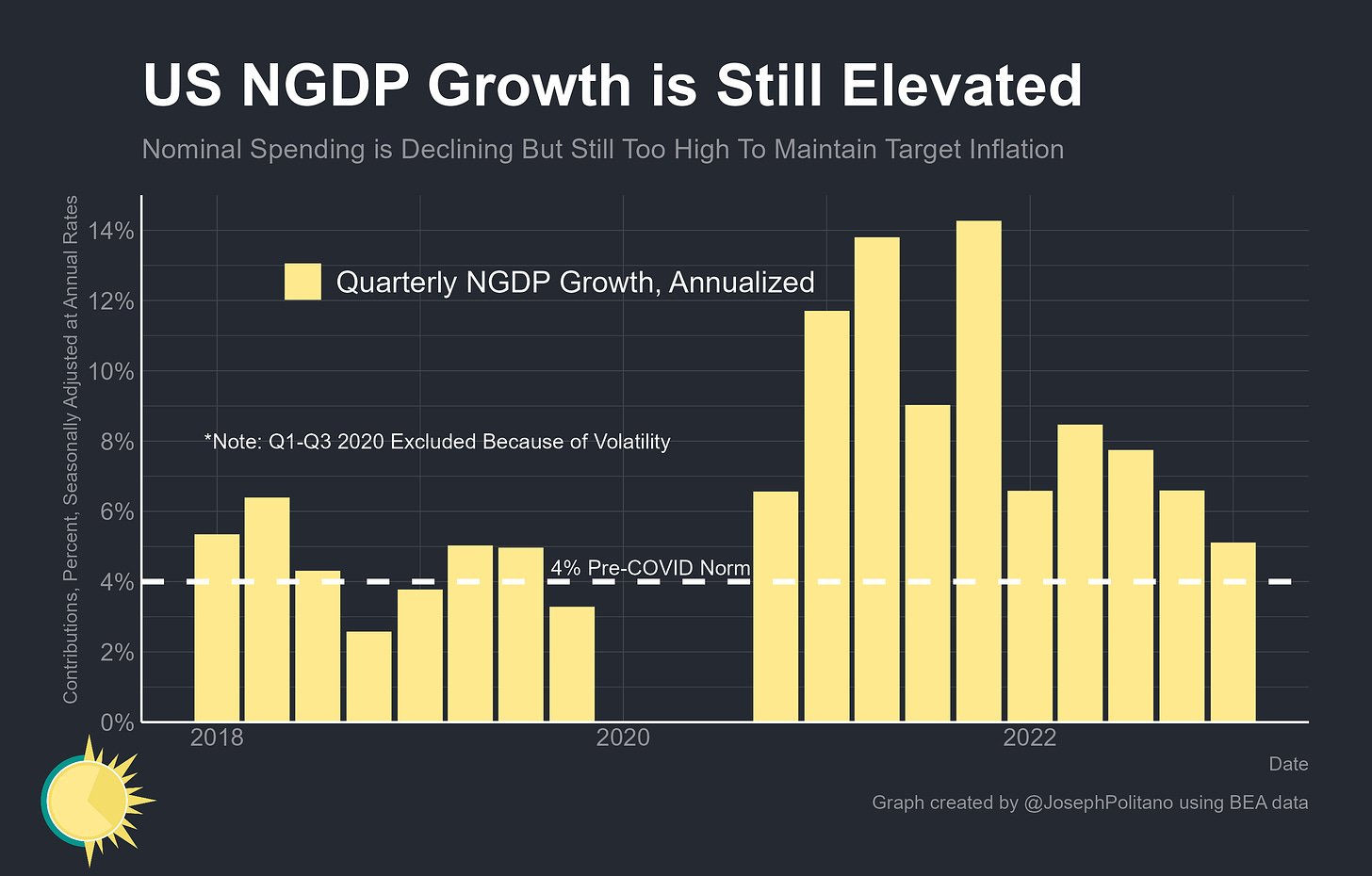

Still, the economy remains too strong for the Federal Reserve’s liking—the case for a pause on interest rate hikes relies on “the cumulative tightening of monetary policy” and “the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation” being enough to further tamp down nominal economic growth and inflation going forward. That cumulative tightening must also not be enough to throw the US economy into a recession—real growth, while positive, has been weak since 2022. Over the last year, Nominal Gross Domestic Product (NGDP, the dollar size of the American economy) has grown by nearly 7%, but growth was only 1.6% after adjusting for inflation.

However, NGDP growth has slowed down considerably throughout 2022—notching the lowest level since the start of the pandemic in the first quarter of this year. It’s still too high for comfort—5% annualized, compared to the roughly 4% level that would be consistent with 2% inflation and closer to pre-COVID norms—and items like consumption growth remain even higher than aggregate growth, but it has made significant ground towards target levels without falls in employment or the onset of a recession.

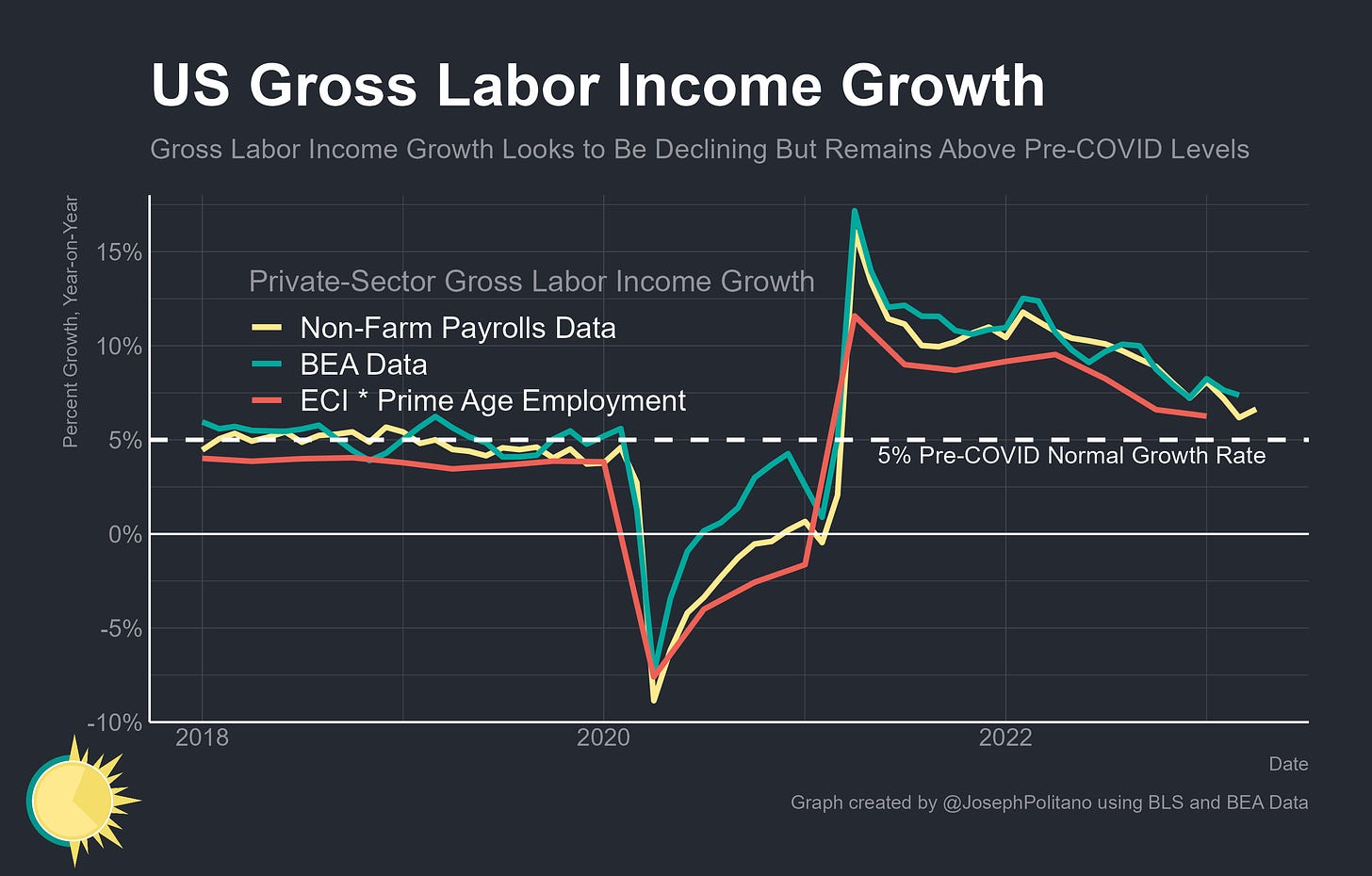

Growth in Gross Labor Income (GLI), the aggregate earnings of all workers in the economy and arguably the best way to measure cyclical economic strength, also continues to decelerate towards something resembling a pre-COVID normal. Both robust real-time measures derived from the Employment Cost Index and household employment levels and more frequent non-farm payroll data indicate GLI growth of only 6.2% and 6.6%, respectively, over the last year (compared to roughly 5% pre-COVID norms). For a Federal Reserve that is mostly now worried about the impacts of inflation on core services, normalizing GLI growth should be a welcome harbinger of decelerations in housing prices and prices for labor-intensive nonhousing services.

Broadly speaking, we are still seeing some of the decelerations in cyclical nominal growth necessary to restore inflation back to target—but not all of what’s needed, and to the degree underlying economic data continue to come in hot it will take longer than previously anticipated for the Fed to achieve its goal. Yet by the same token, a longer and steadier cooldown likely minimizes the chance of the kind of rapid economic collapse that has been most feared since the Fed began tightening policy last year. The economy has so far proven more resilient to rate hikes than previously expected—and that has extended the timeline for fixing inflation while also reducing the still-elevated chances of a recession.

America’s Real Strength

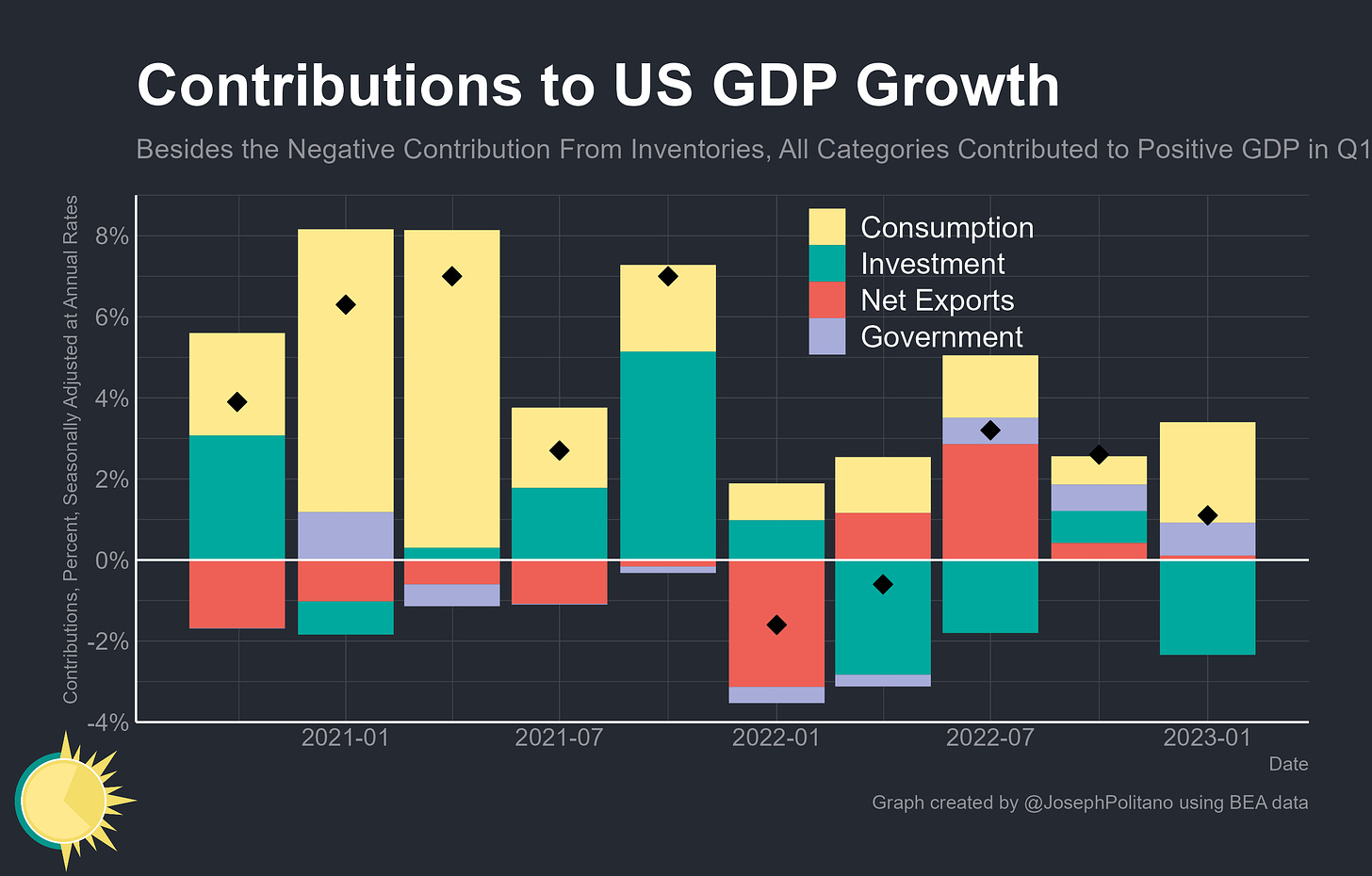

A year after the two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth that precipitated peak recession fears, the US has now posted three consecutive quarters of positive real growth. The low-but-positive Q1 number was stronger than it first appeared—consumption, government spending, and net exports all contributed to headline growth, with a major fall in investment being the main detractor. Yet real fixed investment (homebuilding, factory construction, research & development, etc) declined only slightly—it was a deceleration in volatile business inventory growth that drove much of investment’s weakness.

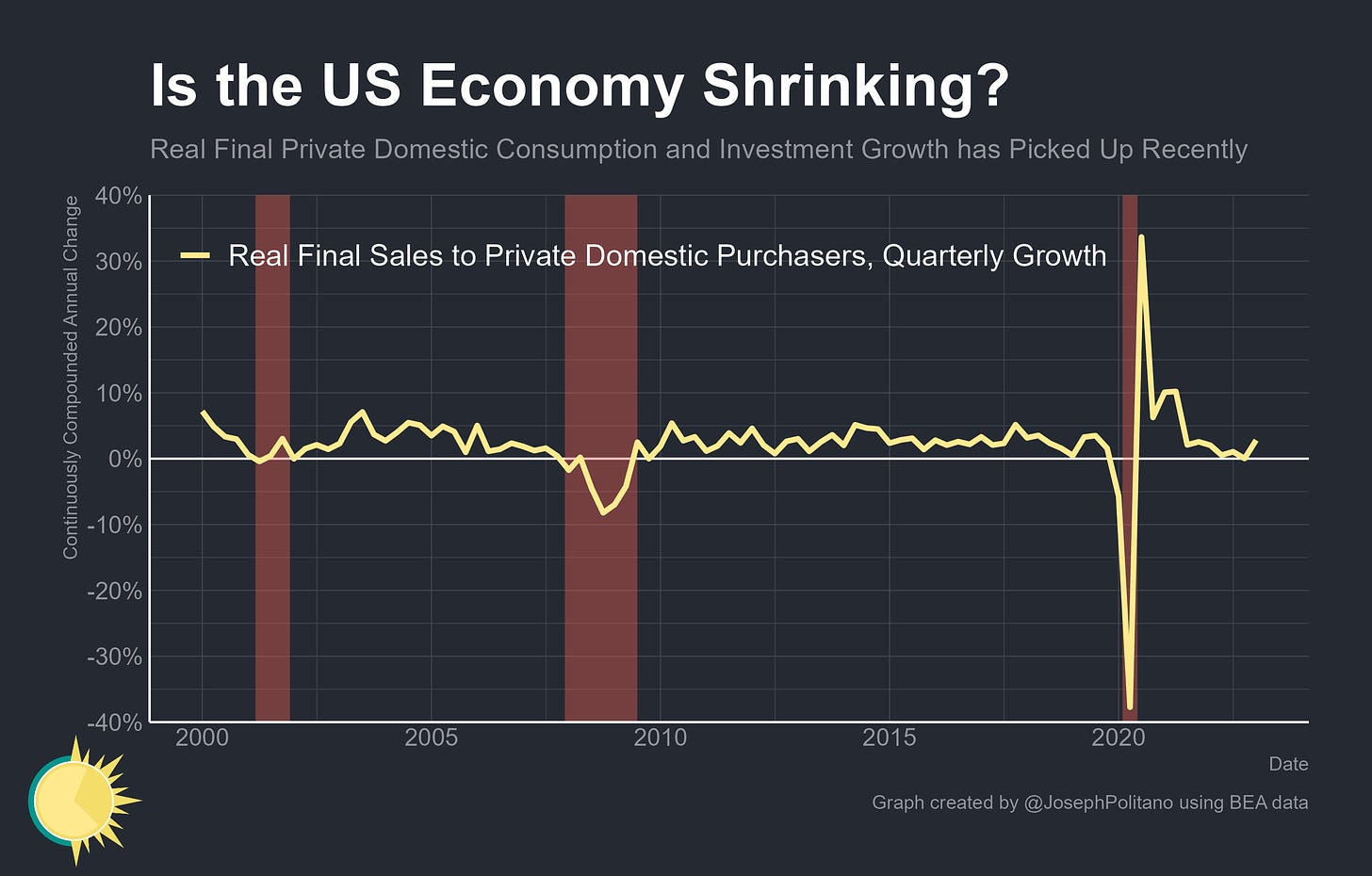

Indeed, real final sales to private domestic purchasers, a niche indicator that reflects growth in private sector consumption and fixed investment, picked up in Q1 after growing extremely little over the last three quarters. Given the importance of the indicator as a representation of core economic growth—it rarely goes negative for even a quarter outside of recessions—it’s another indication that the underlying US economy hasn’t yet begun to contract.

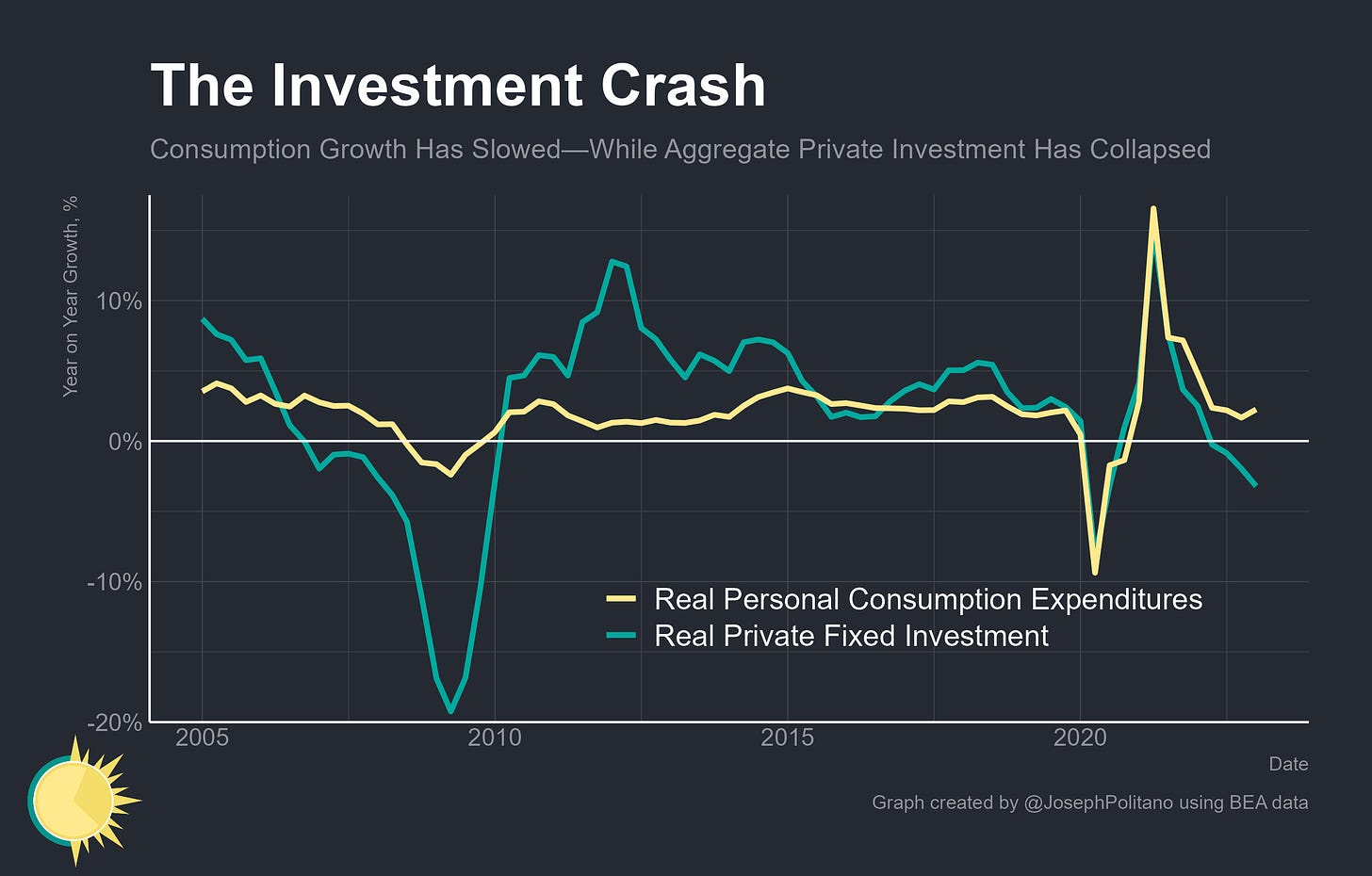

The recent rebound has been propelled by a recovery in real consumption even as nominal consumption slows—which in part reflects improvements to supply and production chains. Roughly 1/6th of the increase in consumer spending this quarter reflected growth in spending on motor vehicles and parts as automobile supply chains continue improving. Year-on-year real consumption growth has rebounded from its 2021 lows, marking a distinct separation from the continued downturn in real fixed investment.

Residential fixed investment, though now at the lowest levels in 7 years, appears to finally be stabilizing alongside mortgage rates. Single-family housing starts have held near a rate of 840k a year since October, and multifamily starts have likewise held near a rate of 540k a year. Nonresidential fixed investment has slowed, but not declined, held up by relatively strong manufacturing investment in the wake of the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act and still-strong Intellectual Property and R&D spending.

In fact, real fixed investment might be stronger than current figures suggest—when projects don’t report the monthly value of construction put in place, the Census Bureau imputes nominal construction spending based on the project’s initial budget and considers a nonresponding project completed once imputed costs hit 101.5% of their original estimated costs. Given how high inflation has been for construction materials, projects have been going consistently over their initial budget, resulting in situations where Census Bureau nonresidential spending data has been consistently revised upwards once initially nonresponding firms submit their data for projects previously imputed as complete. Researchers (Brandsaas, Garcia, Nichols, and Sadovi) at the Fed estimate that the correct value of real nonresidential fixed investment could be 20% higher than what is currently being reported using simple predictive models based on other sources of real nonresidential spending data. So fixed investment during the recent inflationary period could be revised upwards significantly—adding further strength to recent economic data.

Nominal Growth, the Labor Market, and Inflation

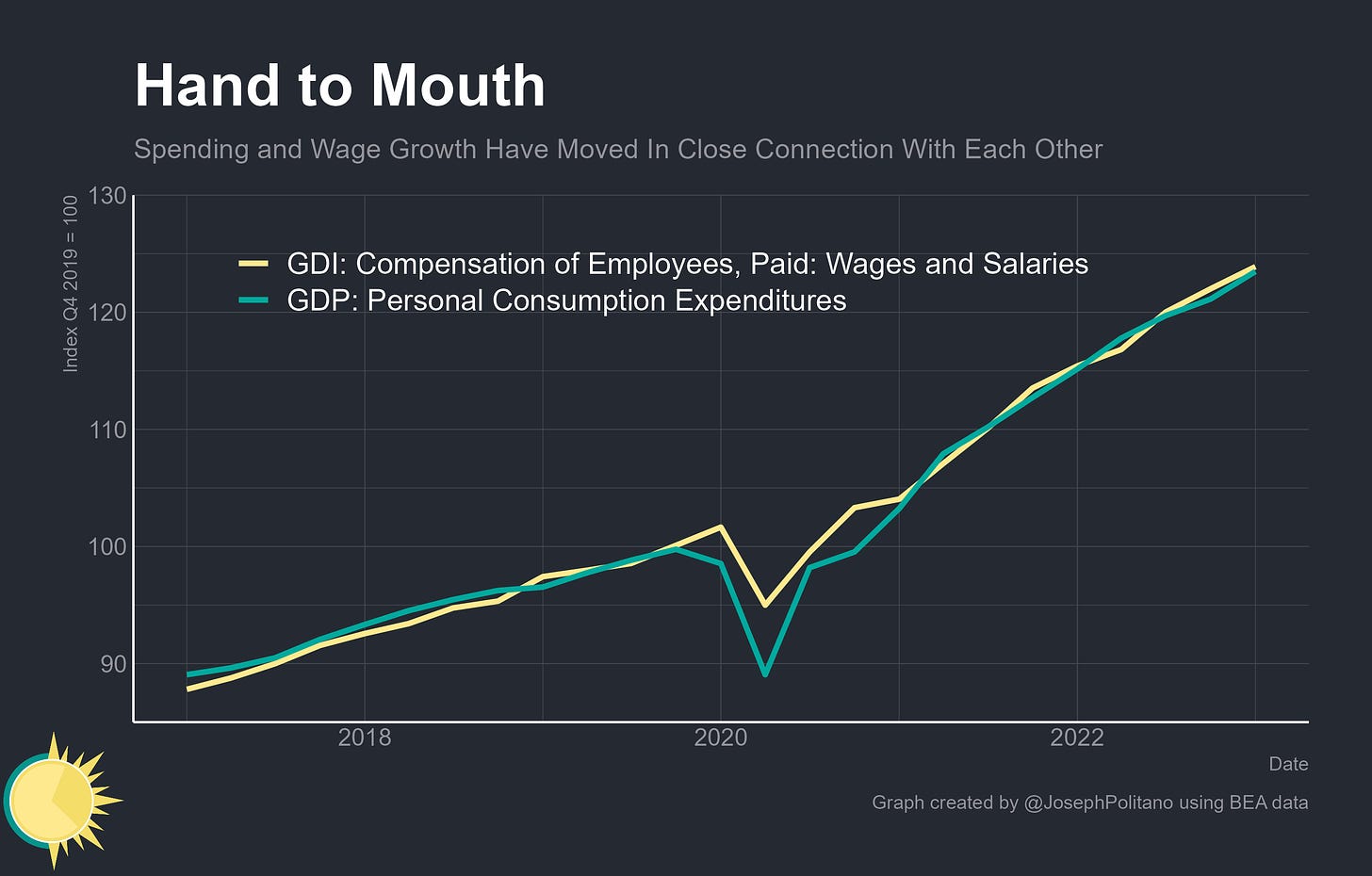

Still, getting inflation back down to target will still require a further slowdown in gross labor income growth. Despite the massive pandemic-era stimulus measures and shifts in borrowing behavior, aggreagte nominal consumption spending has moved essentially in lockstep with aggregate wages since the start of 2021 as Matt Klein has repeatedly highlighted. Unsustainably high consumption growth is part and parcel of rapidly-growing household incomes, which still have to decelerate to get inflation back to the Fed’s 2% trend.

Yet the labor market has also cooled substantially over the last year without entering recession territory. Growth in average hourly earnings has fallen from 6% to just under 4.5%, and the more robust compositionally-adjusted Employment Cost Index has slid from 5.7% to 5% without an increase in the unemployment rate.

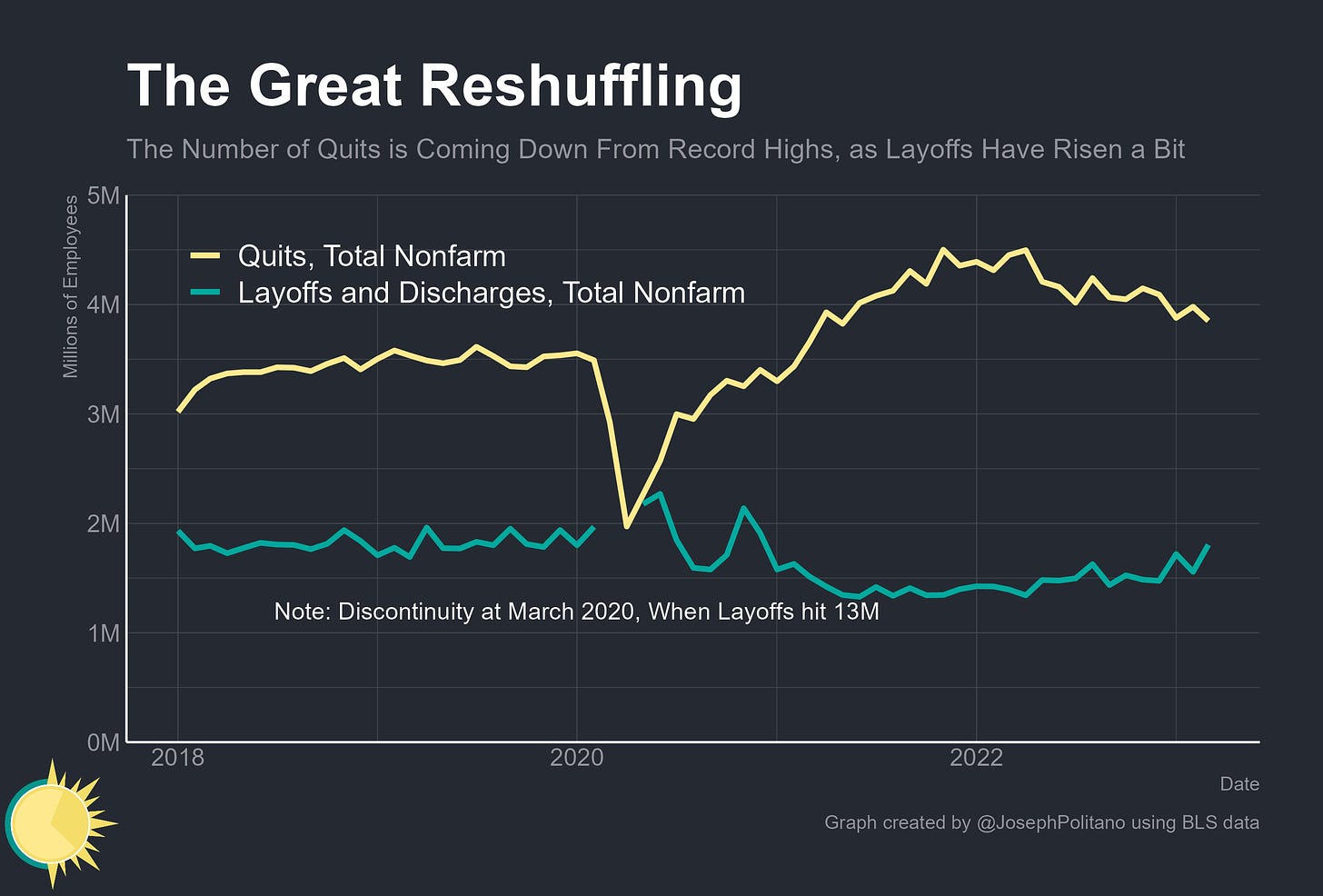

Leading indicators for labor market strength and gross labor income growth have also been weakening substantially. The number of workers quitting each month has fallen from a high of 4.5M per month in early 2022 to only 3.9M per month now, and the number of workers laid off each month has increased to pre-pandemic norms in recent months. Continuing unemployment claims also remain above late-2022 levels and closer in line with pre-pandemic averages after a recent rebound.

That has all helped to decelerate nominal spending growth from the massive highs seen in 2021 and 2022 to a more reasonable-but-still-historically-high level. Per-capita spending increased by 6.7% over the last year, compared to a long-run norm of about 4%, with quarterly growth actually rebounding a bit at the start of this year. For inflation to get under control, spending growth will have to decelerate further.

Conclusions

When the FOMC sat down to make their economic projections back in March, the median participant expected the unemployment rate to reach 4.5% by year-end, only slightly more optimistic than the December 2022 projection of 4.6%. As time has moved on those predictions seem more and more unrealistic—for the unemployment rate to reach 4.5% by the end of the year, it would have to rise more than 0.1% each and every month between now and the end of the year. Presuming no change in labor force size, that would require sustained net employment losses averaging roughly 200-250k per month, a pace consistent only with the absolute worst US recessions.

Yet debt markets aren’t pricing in the chance of an imminent calamitous downturn—high-yield corporate bond spreads, which can proxy for default risk at major businesses and are therefore an important recession indicator—actually remain below their 2022 highs despite the run-up caused by the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and other regional US lenders.

The most likely outcome at the next FOMC meeting is that participants will once again be forced to revise their forecasts—both by extending the time frame before which they expect to see economic contraction and minimizing the size of the contraction expected. The runway is getting longer, and hopefully the landing is getting softer.

Why not "Switched Jobs" than "Quits"? I still feel "Quits" buys into the whole horrible "people too lazy to work" mentality. Here in WV, its the running grumblings from The Employer Class.

Glad for the slow down without a sign of crash, but honestly pretty disappointed that inflation has gone sideways. Might do my part to add to the quits and decrease some consumption soon.