America & China's Chip Race

China's Semiconductor Buildout Continues Despite Global Sanctions—While the US Tries to Catch Up

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 44,000 people who read Apricitas!

Over the last few years, the US government has begun to view the semiconductor industry as a lynchpin of its economic security and prosperity. Shortages of chips contributed to factory shutdowns worldwide and a subsequent burst of inflation, record amounts of chips became necessary for the functioning of a much more online remote-work world, and the advanced subset of chips became fundamental to the Artificial Intelligence networks currently exploding in popularity. Thus American policymakers have taken a much more activist stance towards the semiconductor industry, implementing a two-pronged strategy to secure a domestic chip supply chain and deny one to geopolitical rivals like China.

The first prong of that strategy was a major industrial policy push to support domestic chip manufacturing—Congress passed billions of dollars in subsidies under the CHIPS Act to incentivize semiconductor manufacturers to build cutting-edge fabricators within the United States. That spurred an unprecedented buildout of manufacturing capacity, with spending on the construction of electronics factories skyrocketing since 2022 and continuing to hover near all-time highs. Some of the projects that broke ground earliest are now at or nearing completion, boosting US chipmaking employment and production, while many more still remain under construction.

The second prong of the strategy was implementing significant sanctions and export restrictions to hold back China’s tech industry and hurt the country’s ability to build out its domestic chip manufacturing sector. In October of 2022, the White House announced new controls designed to heavily limit what US high-end semiconductors and chipmaking equipment could be sent to China, leading to swift reductions in export levels for both items. However, Chinese imports of American semiconductors and the equipment used to manufacture them have significantly rebounded since then, and are now roughly matching pre-sanctions levels.

Yet it’s not just American exports that DC tried to restrict—few of the world’s advanced chips & chipmaking equipment are currently made in the US, so Washington needed to work with foreign governments deeper in the semiconductor supply chain to isolate China successfully. For chipmaking equipment, the key players were the Netherlands (home to ASML, the world’s single largest and most advanced semiconductor equipment manufacturer) and Japan (home to Tokyo Electron and a suite of other companies throughout the chipmaking equipment supply chain).

In cooperation with the US, the Dutch and Japanese governments agreed to a suite of export restrictions that barred Chinese firms from accessing the highest-tech semiconductor manufacturing equipment which came into force in mid-to-late 2023. Yet both countries’ overall exports of chipmaking equipment to China have grown to record highs despite the new restrictions, with Dutch exports in particular surging dramatically since early 2023.

In fact, China’s efforts to rapidly build out its own domestic semiconductor manufacturing base have only intensified over the last year. The country continues to import near-record amounts of semiconductor manufacturing equipment—from chipmaking superpowers like Japan & the Netherlands alongside other countries like Singapore, South Korea, and the US—while fixed investment in electronics manufacturing has steadily risen and production of semiconductors has reached new record highs. America’s chip sanctions and industrial policies have thus accelerated China’s push to secure and develop its own semiconductor supply chain, heightening the stakes in the race between the world’s largest geopolitical rivals.

A Detailed Look at China’s Chip Buildout

Chinese manufacturers have long dominated large chunks of the electronics manufacturing supply chain, yet the country remained heavily dependent on foreign fabricators for the semiconductor components that form the backbone of those electronics. Over time, China has steadily increased its semiconductor manufacturing capabilities—but conversely remains heavily dependent on foreign firms for the tools, machines, and equipment used in those semiconductor factories. America restricted China’s access to that imported chipmaking equipment in the hopes of slowing down the PRC’s semiconductor manufacturing buildout, and Chinese firms have responded by accelerating their purchases of what foreign equipment they can access.

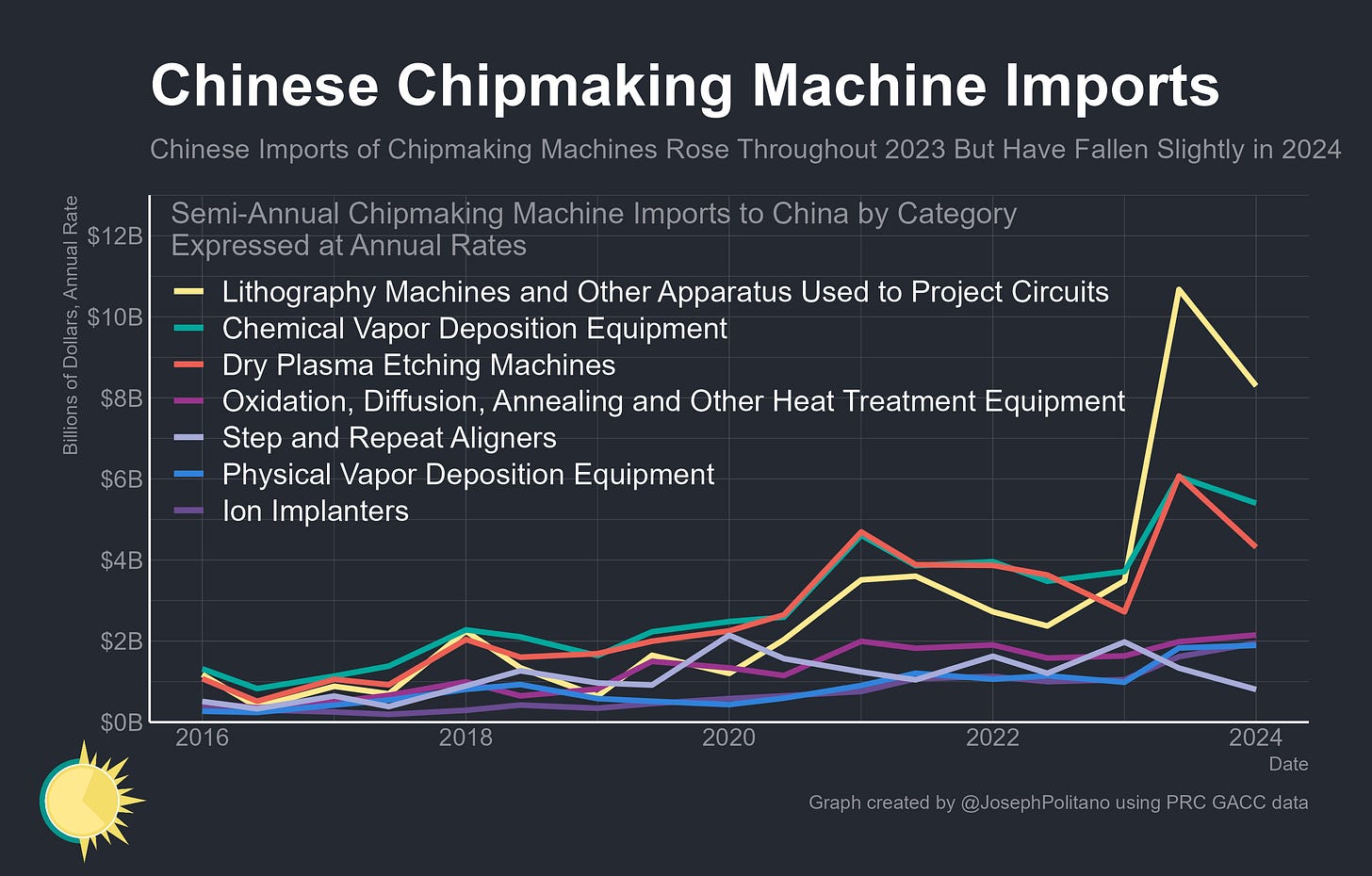

China’s largest semiconductor equipment import are the extremely complex lithography machines used to print intricate circuit patterns onto silicon wafers. Since the start of 2023, China has imported 1,108 units of these at an average cost of $10.1M per machine, with the higher-tech subset imported from the Netherlands clocking in at $34.6M per unit. China has long been banned from purchasing the absolute-cutting-edge lithography machines, and new export restrictions have reduced their ability to buy even some of the high-to-mid-range machines, but they continue to import near-record amounts of the equipment they can buy.

Imports of dry plasma etching machines used to carve out those printed circuitry patterns are also elevated, as are imports of equipment used in Chemical and Physical Vapor Deposition processes that layer essential structures on carved-out patterns. Finally, Chinese imports of the heat treatment equipment used to manipulate semiconductor materials and the ion implanters used to imbue electrical properties on circuitry patterns were both at record highs through the first half of this year. Thus, Chinese investment in fixed assets for computer & electronics manufacturing continues to rise—so far in 2024 it has been 15.3% higher than in the first half of 2023, which in turn was 9.4% higher than in the first half of 2022.

That investment buildout is starting to pay dividends for Chinese domestic chip manufacturing in the form of higher capacity and output. Chinese semiconductor production has more than completely recovered from its 2022 slump, reaching a new record high in April while rising nearly 29% compared to the first half of last year. This increased production has not largely come from moving up the value chain, since the majority of the growth in Chinese semiconductor output is in technologically dated chips that nonetheless remain key for large downstream industries, however, the country also continues to make progress in closing the technological gap with cutting-edge chipmakers.

That increase in domestic chip production, coupled with the sanctions limiting access to the highest-end foreign semiconductors, has put a lid on China’s chip imports. Semiconductors remain China’s largest single import item, but the country’s chip trade has only slowly rebounded even as the wider electronics manufacturing ecosystem booms. Taiwanese electronics production, for example, is up 23% over the last year, but exports to China have actually declined over the same time period. That decrease in import dependence is slowly weakening Taiwan’s “silicon shield”—the geopolitical defense afforded to it by controlling the high-end chip manufacturing that Chinese (and global) supply chains depend on. So far, China still remains highly dependent on outside chips to meet its domestic needs, but the country continues to undertake massive investments designed to wean itself off that foreign dependence. America’s buildout, while still historically large, remains much slower by comparison.

The State of America’s Catch-Up Attempt

Decades ago, American companies used to have total ownership of the high-end semiconductor market and a dominating position over the industry as a whole, but their lead was steadily lost to overseas foreign competitors. US chipmaking collapsed after the 2001 recession, with more than a quarter-million jobs lost in the industry through just the subsequent three years. When the CHIPS Act passed in 2022, it was intentionally designed to rebuild the US semiconductor industry from that extremely limited and atrophied preexisting manufacturing base.

Those efforts are starting to pay some dividends—real domestic manufacturing construction has been smashing records since the CHIPS Act was passed, but that’s only recently starting to impact overall US output and capacity. American industrial production of chips and other electronic components (measured in quality-adjusted output terms, in contrast to China’s measurements based on raw chip count) reached a new record high and is up 7.3% over the last year.

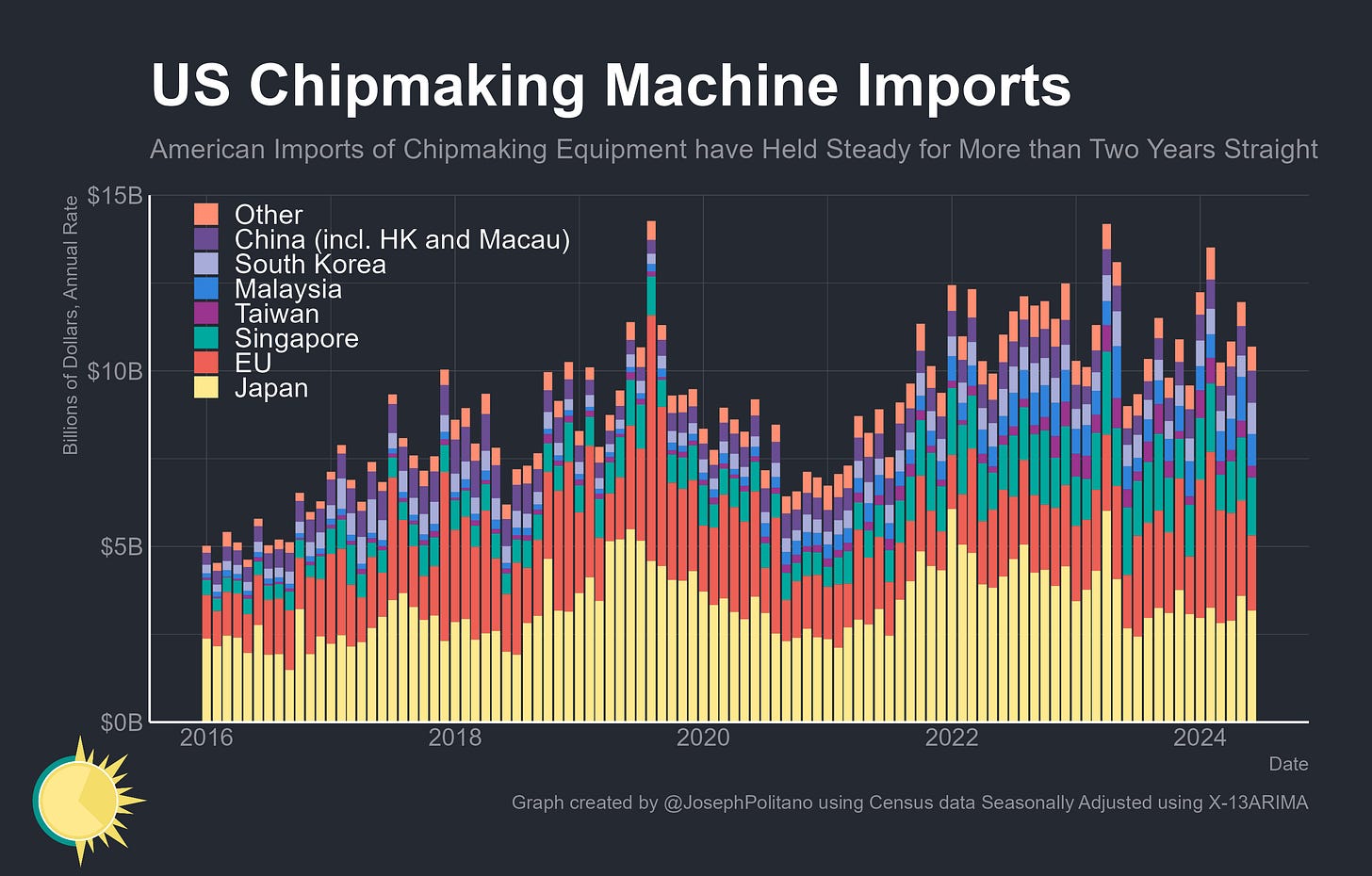

However, despite the CHIPS Act, American imports of semiconductor manufacturing equipment have not meaningfully increased over the last two years. The US already significantly trailed Chinese chipmaking equipment import levels, and that gap has steadily increased as the semiconductor race has accelerated.

American real fixed investment in chipmaking equipment has also not significantly grown, only recently marginally exceeding its pre-COVID peaks. There’s still hope for some upcoming gains, as there is a lag from construction activity to equipment orders to hiring to operation, so imports and investment may accelerate as more fabs are completed and need to be furnished with new equipment. For example, Intel has purchased roughly a year’s worth of ASML’s output of high-end EUV lithography machines—the exact kind banned from export to China—and most of them are slated for US delivery soon. Yet imports would need to rise by extremely large amounts to even approach China’s current levels of investment.

Conclusions

Since the start of America’s semiconductor industrial policy push, chips have only become more important to the geopolitics of global trade. The sector has bounced back from its 2022 slowdown, racing forward on the strength of an increasingly digital world and the ravenous demand of the growing Artificial Intelligence sector. American spending on the construction of new data centers, key to the training and operation of those advanced AI models, has now skyrocketed to a record-high pace of $27B per year.

Amidst rising demand, the confluence of the CHIPS Act, intensified sanctions, and the growing race to build out competing semiconductor supply chains has thus already shifted the relative balance of the semiconductor trade. American orders for Taiwanese semiconductors have risen significantly from their late-2022 lows—and have been consistently exceeding Chinese orders for most of the last two years—making the US now Taiwan’s most important customer.

Likewise, output of semiconductor equipment in key manufacturing nations has held at or near their all-time highs despite a post-2022 slowdown. Newly revised data from the Dutch government shows chipmaking equipment production increased by 150% between 2018 and early 2023 before stagnating in the intervening year and a half since, while Japanese production doubled over the same timeframe and has similarly bounced around 2023 levels for more than a year.

US-China competition in the semiconductor industry is likely to only intensify further—just within the last few months, America has imposed higher tariffs on Chinese chips alongside a wide variety of other goods, to which China vowed retaliation. Neither country feels they have an off-ramp to the ongoing escalation cycle that has endured for nearly a decade at this point. That’s been good news for the companies building semiconductor fabricators and chipmaking equipment—gold rushes tend to benefit shovel-makers—but even these firms and their host countries will increasingly find themselves forced to choose a side. America and China are locked into their race to build out competing chip supply chains, with all the costs and risks that entails.

"American industrial production of chips and other electronic components (measured in quality-adjusted output terms, in contrast to China’s measurements based on raw chip count) reached a new record high and is up 7.3% over the last year."

When you click on the link, you see that the rate of increase is lower than pre-pandemic.

"Quality-adjusted" lol When you start doing that, you can manipulate stats to fit your narrative.

Nice article. Well done 🙌🏼