Americans are Quitting Their Jobs: Here's Why That's a Good Thing

Tight Labor Markets Have Enabled A "Great Reshuffling" of Workers

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

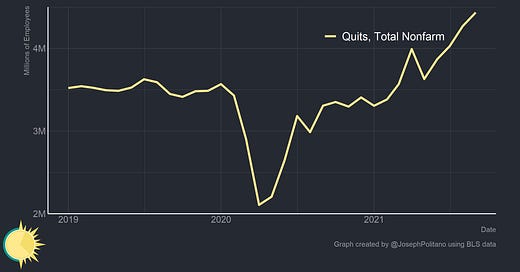

4.4 million Americans quit their jobs in September—setting an all time record high for the third consecutive month. A poll from Morning Consult reports that 46% of full-time employees are considering switching jobs, and 20% are already looking. Professor Anthony Klotz is calling it “The Great Resignation”—a radical rethinking of our relationship to work in direct response to the traumas of COVID-19.

However, far from disengaging from the labor market entirely, quitting workers are more likely to be jumping ship to a better job opportunity. Retirements are not increasing, though re-entry from retirement decreased slightly and is now picking back up. Hires are way above trend, as are average weekly hours worked (though data on hours worked suffers from compositional issues). It is not so much of a “Great Resignation” as a “Great Reshuffling”—workers are quitting to start better, higher-paying jobs elsewhere.

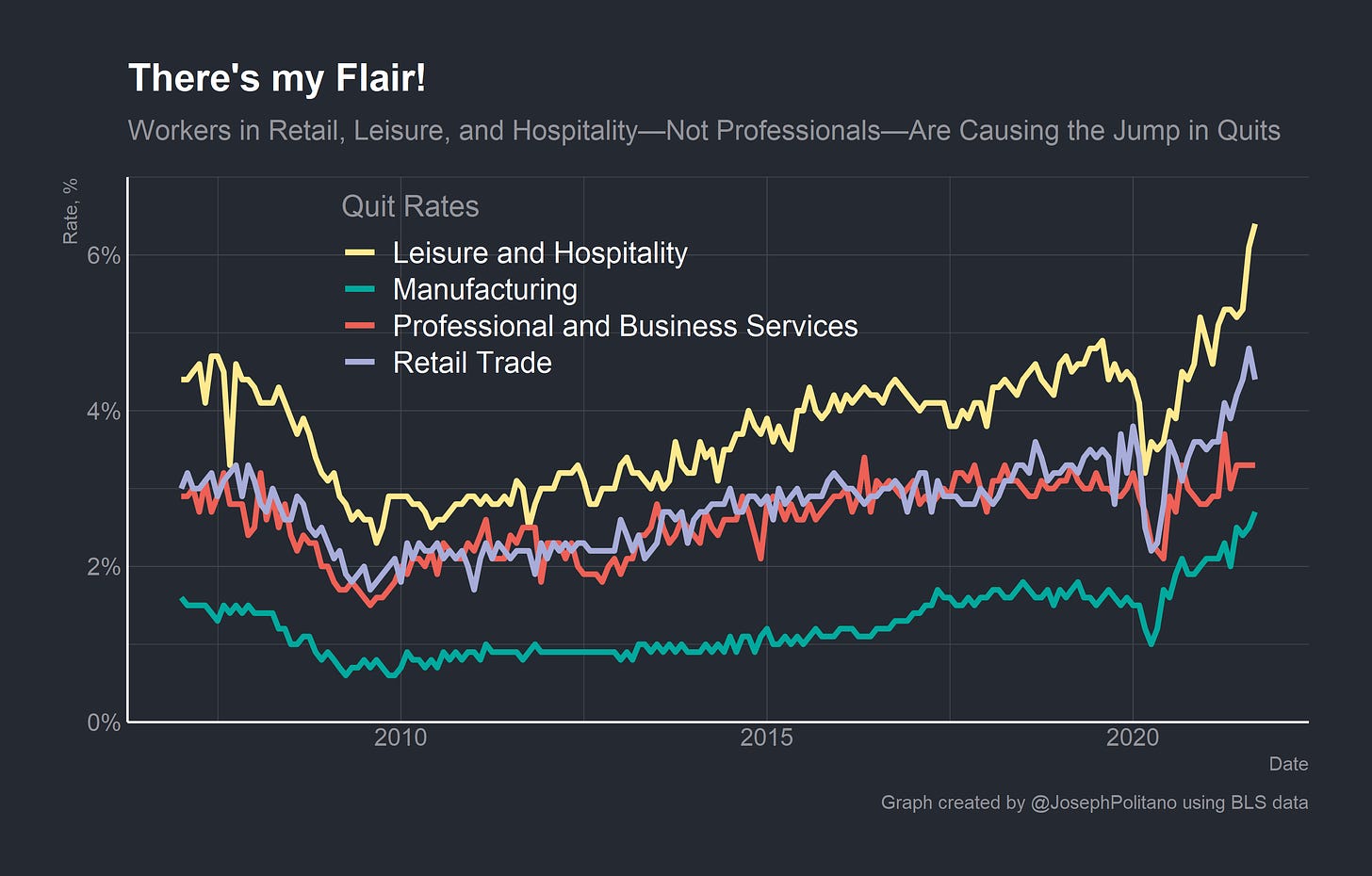

The principal drivers of the Great Reshuffling are also not who you’d expect. Well paid business professionals are not the ones searching for greener pastures, it is instead younger workers in lower paying industries that are quitting their jobs at record rates. Large companies aren’t the ones losing workers either, it is small and medium sized enterprises that are struggling to retain their employees.

This is not to undersell the importance of the Great Reshuffling, which is nothing short of a sea change for American workers. The strengthening economy and tightening labor market are boosting workers’ bargaining power and enabling low income employees to increase their incomes and pursue new career opportunities. For the first time in decades, employers are competing for workers instead of the other way around. The result will be an economy with higher productivity growth, rising wages, and shrinking inequality.

The Great Reshuffling

3% of all American workers left their jobs in September alone, completely blowing away the pre-pandemic record of 2.4%. It took until 2015 for quits to recover to their pre-Great Recession level, but it only took a single year for quits to reach their pre-pandemic level. Hiring is also on a tear, clocking in at 6.4 million per month as corporations try to fill positions and bring workers back.

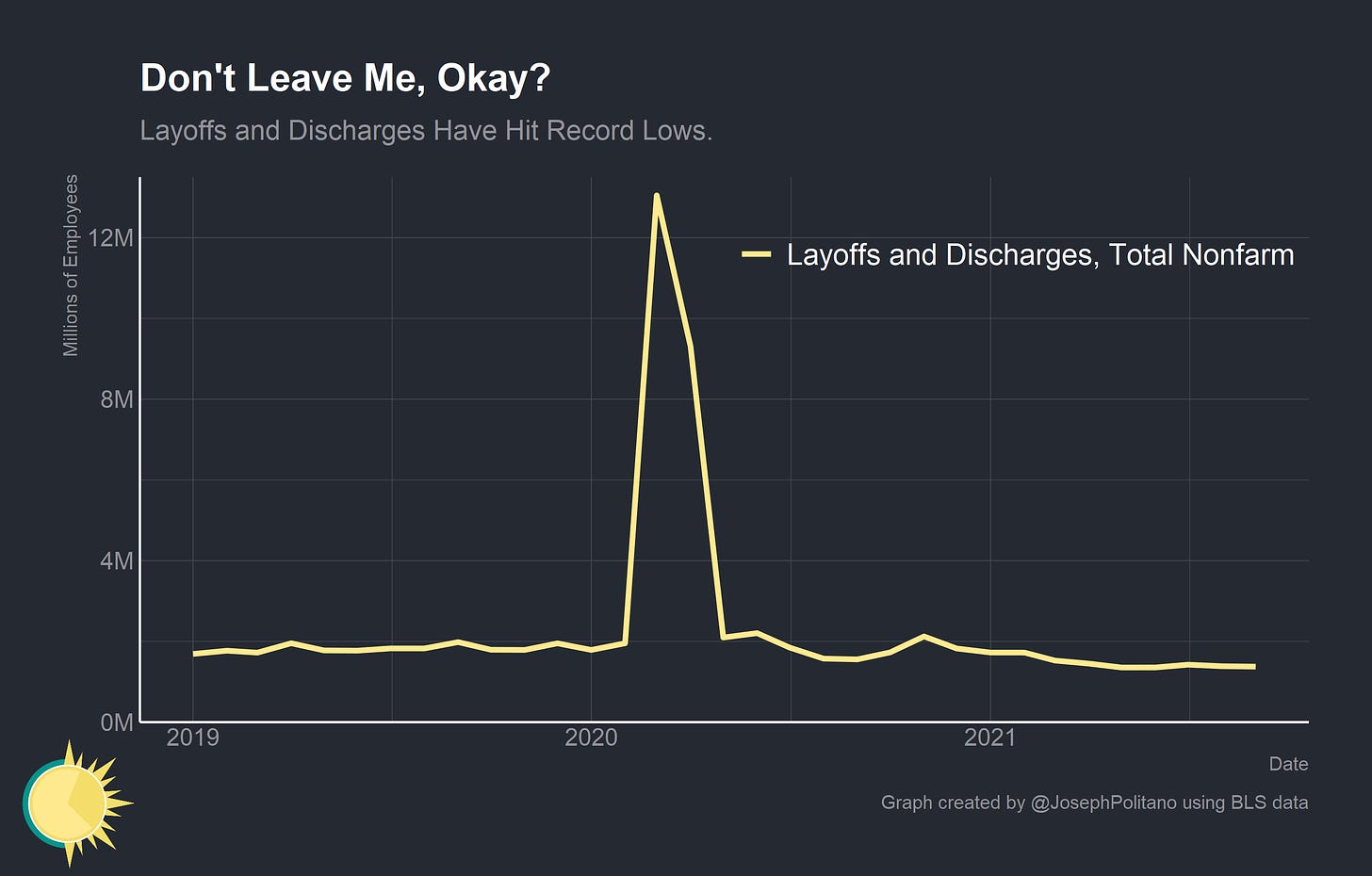

On the flipside of quits, layoffs and discharges have hit record lows after an unprecedented spike at the onset of the pandemic. Only 1.4 million workers were given pink slips in September as employers simply cannot afford to lose additional personnel.

In general, unemployment increases during recessions because hires decrease more than quits while layoffs trend upwards. The normal churn of labor markets is disrupted as recent college graduates, parents returning from childcare leave, and other possible labor market entrants simply cannot find work. Promotions are halted, firm growth stunts, and workers’ career paths are blocked, leading to a halt in the vacancy chains that create aggregate employment growth. Employed workers think “there but for the grace of God go I” and cling to their jobs out of fear that quitting will preclude them from finding work again.

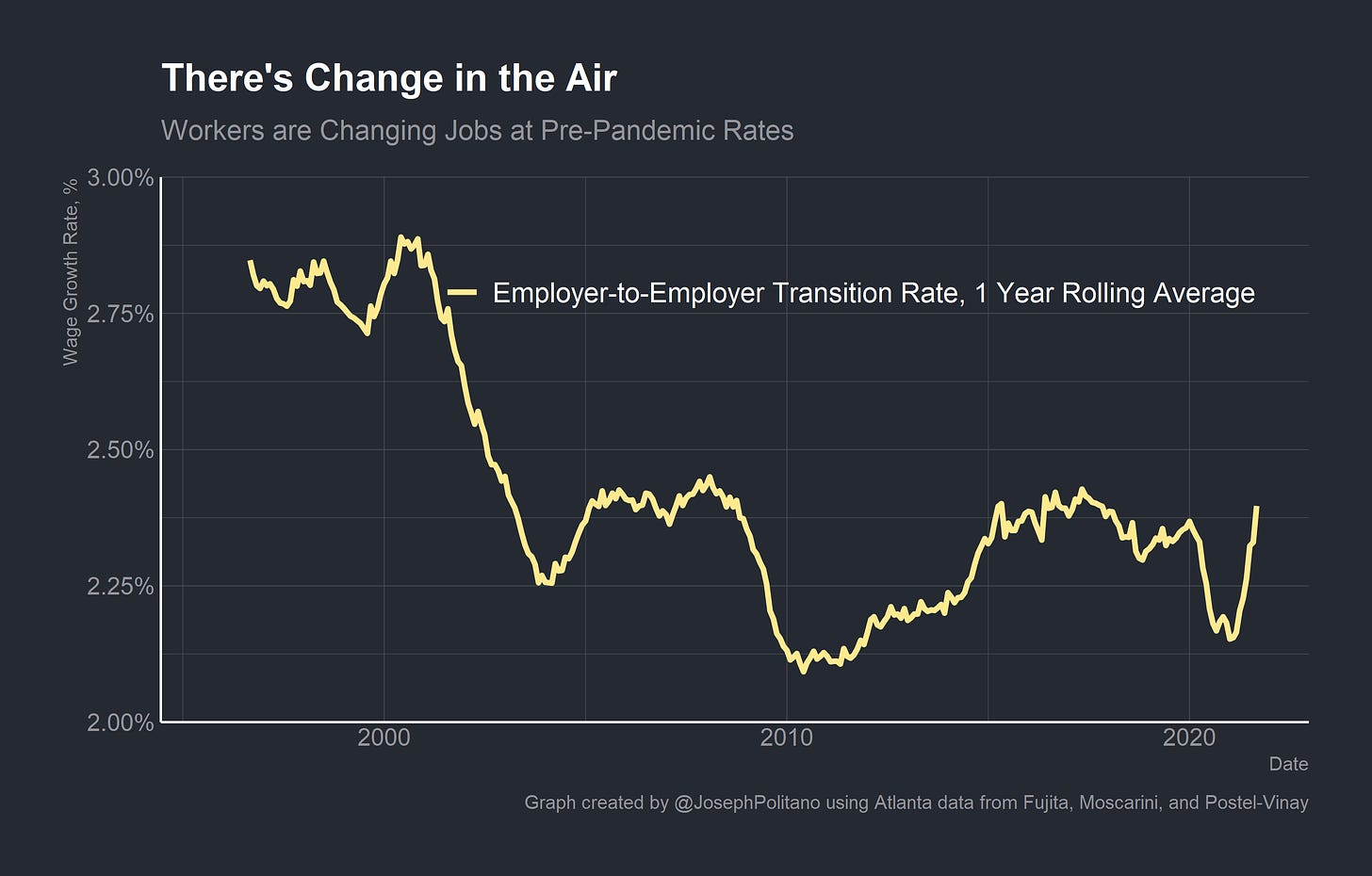

Instead of a hiring decline, however, the pandemic has seen robust hiring growth. First companies were pulling primarily from the unemployed, recalling furloughed personnel and the temporarily unemployed. Nowadays, however, they are increasingly poaching from the already employed. The graph above measures the employer-to-employer transition rate, which essentially represents the percent of the workforce that left their jobs for a job with another employer in a given month. While it declined precipitously at the onset of the pandemic, it has since rebounded and even exceeded pre-pandemic levels. Workers are feeling confident enough to leave their jobs in search of greener pastures, and companies are expanding operations and boosting pay in order to compete for talent.

Critically, the rise in quits is not a trend driven primarily by well paid white collar professionals. Instead, it is workers in lower pay industries like leisure and hospitality, retail trade, and manufacturing that are quitting en masse. Hiring is also up dramatically in these industries, indicating that intra-industry churn is playing a big role alongside inter-industry churn. These workers also tend to be younger, lower-income, non-white, and subject to the most in-person interaction during the pandemic. The tightening labor market has helped strengthen these workers’ bargaining positions while fostering competition among firms and accelerating investments in productivity-increasing methods and fixed capital. The result of this increased churn and newfound competition for workers has been rising wage growth across the board.

Greener Pastures

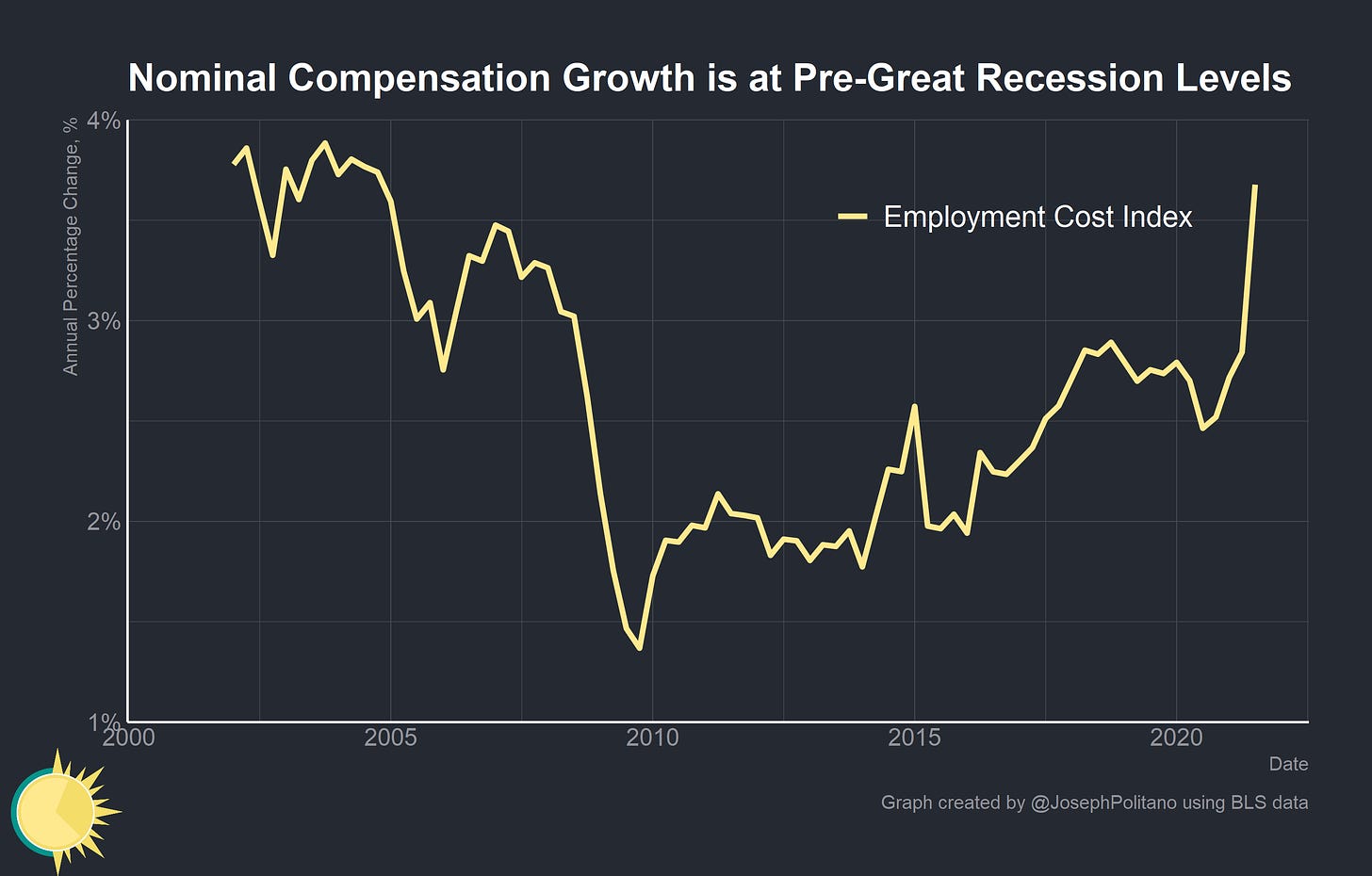

The Employment Cost Index, which measures total compensation in a way that accounts for shifts in labor market composition, is currently showing growth levels that have not been seen since before the Great Recession. Compensation growth is highest in industries with the most quits—annual wage growth is 6% in retail trade and a staggering 8% in food service and accommodations. Essentially, the tightening labor markets is driving higher wage growth as companies fight to retain existing employees and poach workers from their competitions within and across industries. As an example, employment levels for restaurant wait staff essentially stall out while wages increase when labor markets tighten as restaurants compete for workers with each other and with other industries.

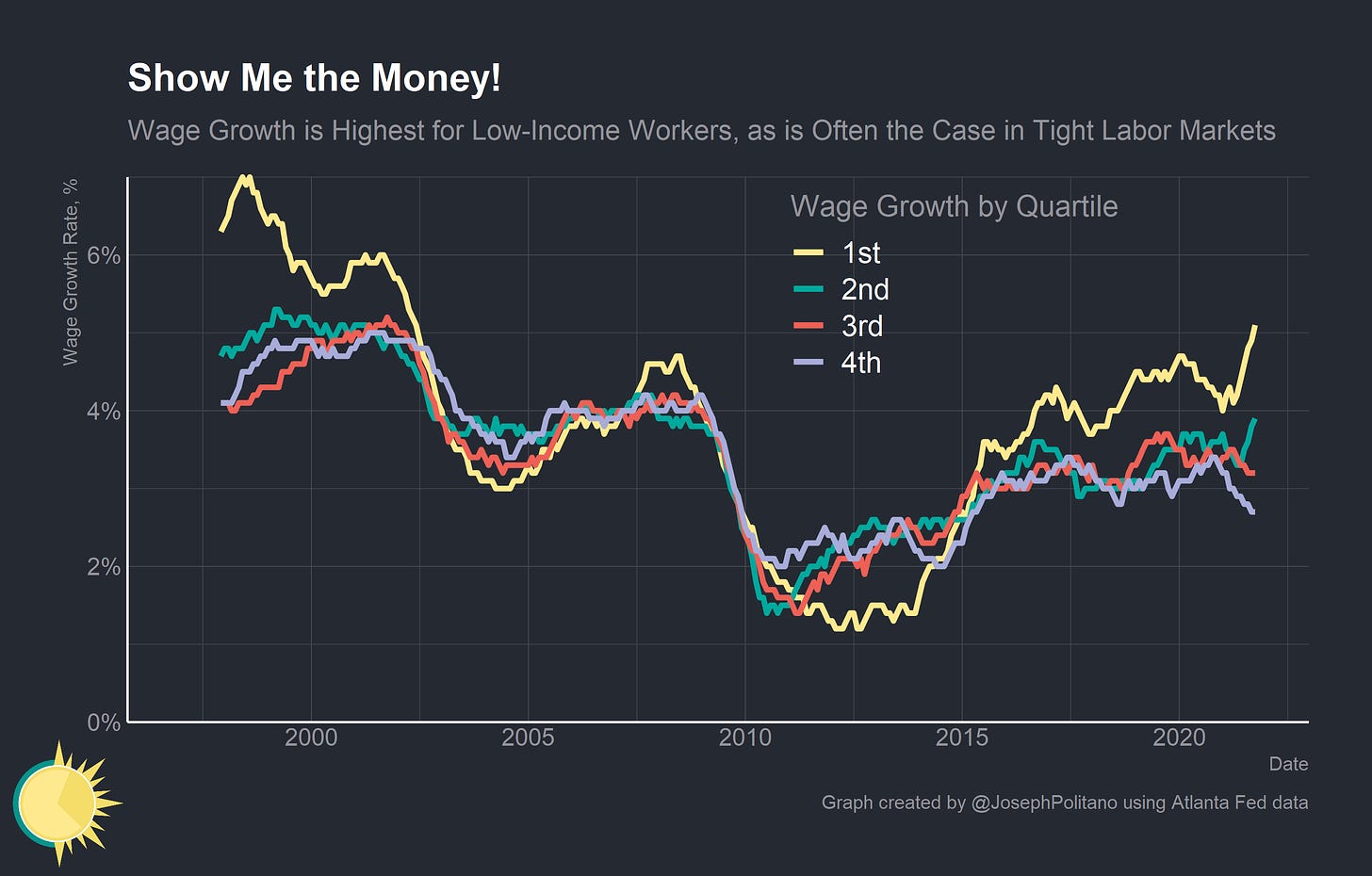

The Great Reshuffling has also caused a rapid increase in wage growth for the lowest income workers, as shown in the graph above. Workers in the 1st quartile—the lowest 25% of all earners—are seeing raises of more than 5% on average. Tight labor markets are decreasing inequality as wage growth for the lowest quartile workers exceeds that of the highest quartile workers. This is in direct contrast to the weak labor markets of the early 2010s where wage growth for low income workers lagged far behind. It is also worth acknowledging that it is the youngest workers who are benefitting most from this situation as firm expansion increases competition for entry-level talent.

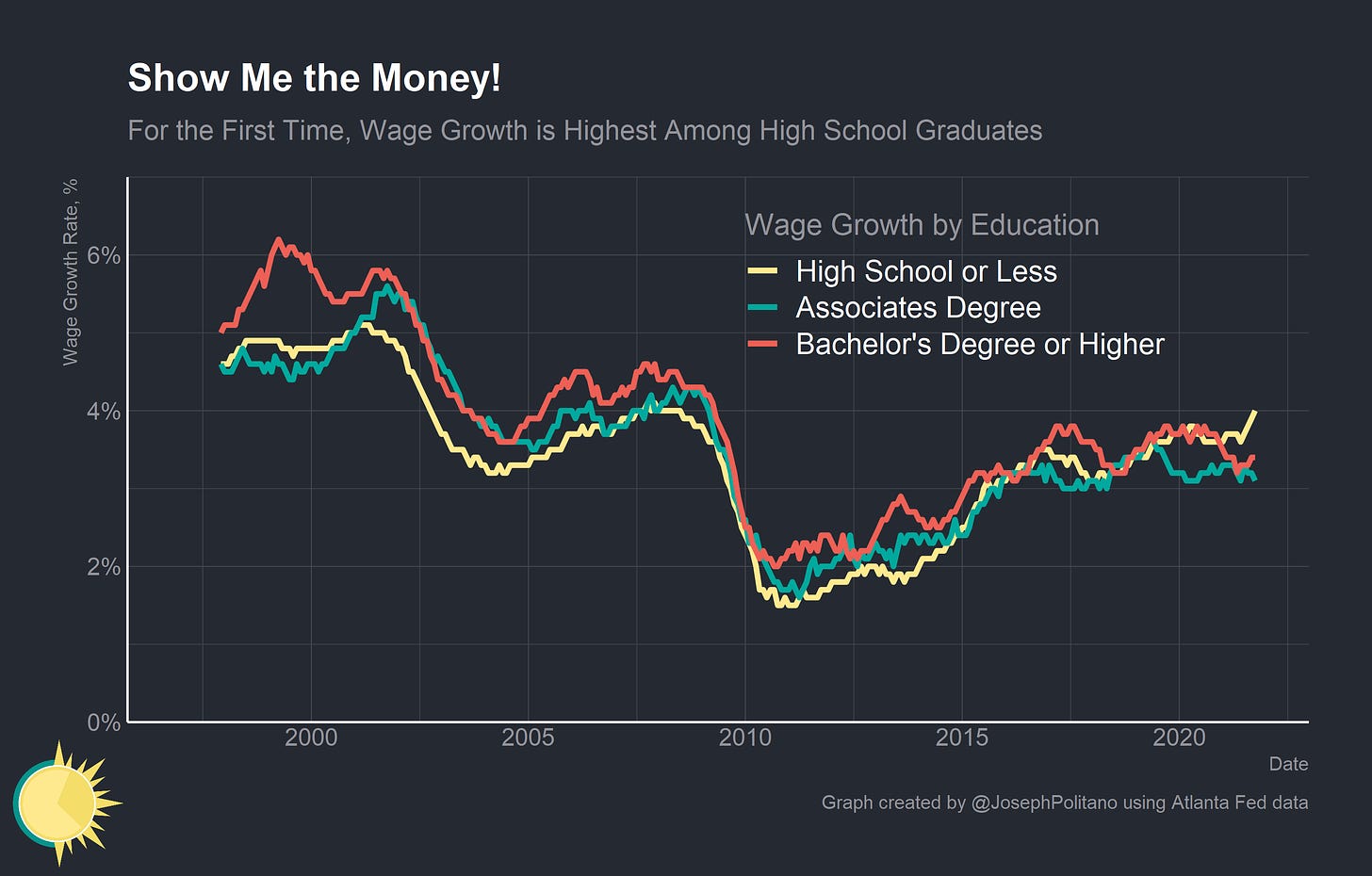

The tight labor market is also counteracting the long run trend of increasing wage gaps between college-educated and non-college educated workers. For the first time since the turn of the millennium, wages for high school graduates are growing faster than wages for college graduates. Across all dimensions, the Great Reshuffling is enabling broad based and inclusive economic growth.

Conclusions

The greatest failure of America’s economy in the 2010s was that low nominal aggregate income growth increased unemployment and decreased real income growth. Americans have been living below their means—accepting worse jobs with lower real wages—since the Great Recession, and it is only within the last year that we have started to see demand side monetary and fiscal policy push the economy back to its maximum growth rate. The Great Reshuffling is a necessary, and welcome, part of the shift towards full employment and maximum economic growth.

Companies whose business models have relied on weak labor markets, high unemployment levels, and low wage growth will have to adapt if they want to retain workers. Take FedEx—the company’s reliance on a network of subcontractors with high turnover for its last-mile package delivery was immensely profitable during the weak labor market environment that persisted in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Today it is being outcompeted by UPS, a company that employs strong economies of scale alongside high pay and a unionized workforce. Empirical evidence shows that Amazon’s self-imposed minimum wages drive up pay for low-wage workers at other businesses as the company intensifies competition for labor. In addition, monopsony—the leverage employers use to set worker pay below marginal productivity—shrinks as labor markets tighten.

An economy where firms are fighting for workers and tirelessly pursuing process improvements that increase labor productivity will be, in aggregate, a much better economy for workers, governments, companies, and investors. Inequality will shrink, poverty will decline, wages will rise, and real output will grow. Companies that cannot compete in this environment will be forced to adapt or fold, but government policy should not be designed to coddle business models that are reliant on weak economies. The Great Reshuffling may not be a radical rethinking of work itself, but it still represents a radical return to the tight labor markets that were the bedrock of American economic excellence in years past.