Americans are Spending Their Excess Savings

The Good, the Bad, and the Complicated of America's Spending Surge

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 6,200 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Throughout the first two years of the pandemic Americans accumulated trillions of dollars in excess savings. Stuck at home or afraid of COVID, they spent far less money than would be expected. Bolstered by government transfers and stimulus checks, they earned far more money than would be expected. Over time they accumulated an aggregate $2.5 Trillion stockpile—and now they are starting to spend those savings down.

Or, well, not exactly. The jump in savings are a mechanical result of how deficit-financed government transfers show up in the official National Income and Product Accounts. For the public sector to run a deficit the private sector must run a surplus; for the public sector to go into debt the private sector must be building up savings. A massive shock to the size of the public sector deficit will create a corresponding large shock to the size of private sector savings—hence why deficit-financed stimulus resulted in excess savings.

It’s also worth keeping in mind the distribution of excess savings. While extremely comprehensive data is sadly lacking, a variety of information still points to the conclusion that the majority of excess savings are held by people in the upper end of the income and wealth distribution. Balance sheet improvements and financial security gains were clear (though marginal) for middle-class people, but the majority of excess savings went to high-income individuals who retained their jobs/assets but reduced their consumption during the pandemic.

Neither of those points means that excess savings are fake—just that they’re more complicated than they initially appear. It also means that we have to be careful in analyzing how Americans are spending down those savings as the economy continues to reopen.

An Excess Penny Saved…

First, let’s clarify some points. Personal saving—in the National Income and Product Accounts—represents the sum total of aggregate personal income that is not spent on aggregate personal outlays. In other words, if you summed together all the wages, dividends, government transfers, etc of US households and subtracted out their consumption spending, taxes, interest expenses, etc you would arrive at personal saving. That leaves a lot of ways for personal saving to manifest—increased bank account balances, additional retirement contributions, cryptocurrency purchases, paying down the principal of mortgages or other household debt, and even home remodeling (technically categorized as “residential investment”). In other words, it is not like there is precisely an additional $2.5 trillion sitting in household bank accounts because the personal saving rate has increased by $2.5 trillion.

It’s also important to distinguish between the flow of saving and the stock of savings. The personal saving rate represents the share of income saved in a given time period (say, one month) while personal savings represent the total value of accumulated assets. Excess savings is the rise in cumulative total assets that is attributable to an abnormal rise in personal saving. As an example, in April 2020 the personal saving rate hit a record 33% (compared to about 7% pre-pandemic), boosting excess savings. Today, the aggregate personal saving rate is 4.4%, drawing down excess savings.

What’s now pulling the stock of excess savings down? It’s chiefly a rise in nominal spending, not a drop in personal income. By mid-2021 personal outlays had bounced back to their pre-pandemic trend and by early 2022 they jumped far above trend. As the personal saving rate shrank the cumulative stock of excess savings began to decline. So far, Americans have spent down approximately $150B of the $2.5T in extra aggregate savings that they accumulated in 2020 and 2021.

This graph shows the cumulative deviation from trend for both personal income and personal spending. The pattern is pretty clear: aggregate incomes have hovered above trend for most of the pandemic but were primarily buoyed by the three rounds of stimulus checks while personal spending remained well below trend for all of 2020 before steadily jumping above trend in 2021.

The above chart disaggregates personal income and outlays into their constituent parts to determine each category’s cumulative contribution to excess savings. A positive number indicates that the component increased aggregate personal savings and a negative number indicates that the item decreased aggregate personal savings. So “personal consumption expenditures” are listed as a positive number because the cumulative decrease in personal consumption expenditures resulted in increased personal savings while labor income is listed as a negative number because the cumulative decrease in labor income resulted in decreased personal savings1.

The biggest positive contributors to excess savings are obvious; increased government transfers and decreased personal consumption expenditures. Those categories more than offset the drop in labor and capital income that occurred in 2020 and 2021. But again remember that for the public sector to go into debt the private sector must be building up savings; a positive contribution from government transfers only indicates that deficit financed spending was directed at households. Also, it would be hard for the contribution from government transfers to decrease significantly as definitionally public spending is classified as transfers and public revenue is separately classified as taxes.

Still, it is important to note that the big downward shifts in the stock of excess savings come from rising tax payments and personal consumption expenditures. The rise in consumption spending comes from a steady increase in services spending as the economy reopens, but the rise in taxes is a bit more complicated. Comprehensive data is unfortunately unavailable, but it looks as though rising tax receipts come from a combination of higher income taxes thanks to rising wages and employment levels alongside a jump in capital gains taxes given appreciating asset prices.

This brings up another important aspect of the national accounts data; there are limited places for the excess savings to go. Some chunks are spent on home remodeling and other physical investments, but the financial assets have to either be destroyed or transferred to other sectors. The main three sectors that excess savings could end up in are corporate, government, or foreign. The corporate sector is already absorbing some excess savings; undistributed corporate profits (analogous to the personal saving rate for households) has shot up since the start of the pandemic.

The government sector is also absorbing excess savings. As mentioned before, government receipts have increased significantly—and April saw a record high federal budget surplus of over $300B as Americans paid their yearly tax bills.

The foreign sector is also absorbing a large chunk of excess savings. The US trade deficit shot up to a record high of more than $150B in March (though admittedly this was partially due to increased throughput at domestic ports, as I’ve discussed before). That means foreigners received a net $150B of American-owned financial assets, pulling down excess domestic savings.

Now, it is important to mention here that it remains wrong to reason from accounting identities regarding excess savings. While it is true, definitionally, that for domestic savings to decrease then the savings of the government, foreign, or corporate sectors must increase it is not true that an increase in non-household savings will cause a decrease in domestic savings. As an example, an explicit attempt to increase the trade deficit could hypothetically result in lower domestic employment and lower government income tax revenues, thereby keeping aggregate domestic private savings constant even as the trade deficit increased.

It is also important to note the shifts in the composition of financial assets even as aggregate savings remain unchanged. The Federal Reserve’s Quantitative Easing can result in the transformation of household/corporate Treasury/MBS assets into bank deposits, and Quantitative Tightening can do the opposite. Indeed, that is exactly consistent with the real life bank deposit data; aggregate deposits increased tremendously at the beginning of the pandemic as QE went into effect and are decreasing now as QT goes into effect.

The Micro View

Lets take a step back from the aggregate data and look at household balance sheets at a micro level. The Federal Reserve carries out the Survey of Household Economic Decisionmaking (SHED) every fall to gather basic data on the financial health of Americans. If you have ever heard that a large percentage of Americans could not cover a $400 emergency expense with cash or equivalents, that comes from the SHED. There’s a different question that’s more relevant here though: the share of households with a 3 month emergency fund. Looking back at the last three years of SHED data, it becomes clear that households saw a real improvement in their financial security, but that the effects were marginal at best and heavily concentrated among middle-class families. Some of the survey evidence from SHED helps corroborate this idea—15% of households making 25-50k a year saved the largest portion of their Child Tax Credit compared to 54% of households making $100,000 or more.

At some level, this should not be surprising. The top 1% hold about 30% of all assets in America, and the top 10% earn about 30% of all income. We know that these households have the highest discretionary spending budgets, lowest marginal propensity to consume, and were least likely to lose their jobs during the pandemic. It makes sense that they would end up holding the bulk of excess savings, stimulus checks or not. Critically, it’s also worth putting the $2.5 Trillion in excess savings in context against the $35 Trillion increase in aggregate household net worth—which also disproportionately benefitted higher-income and wealthier Americans.

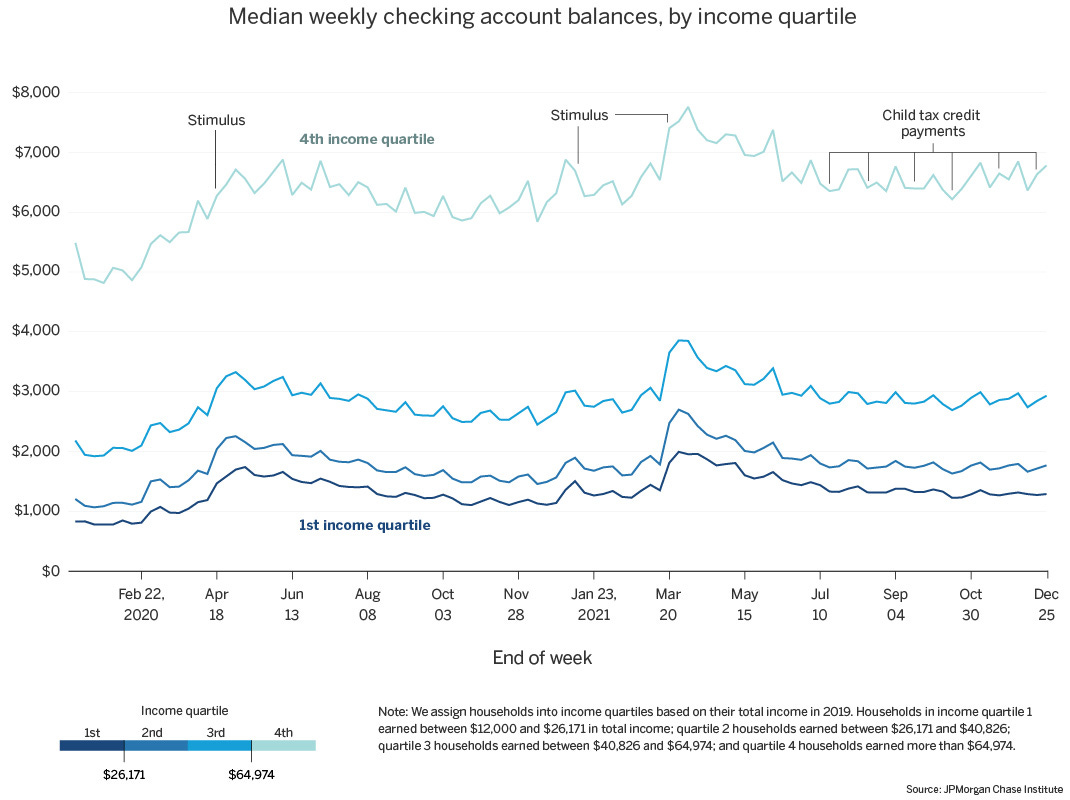

Data from the JP Morgan Chase Institute on checking account balances also helps show where the majority of excess savings ended up. High income households saw the highest raw increase in median checking account balances, while lower income households saw their balances grow by a larger percentage but a smaller total amount.

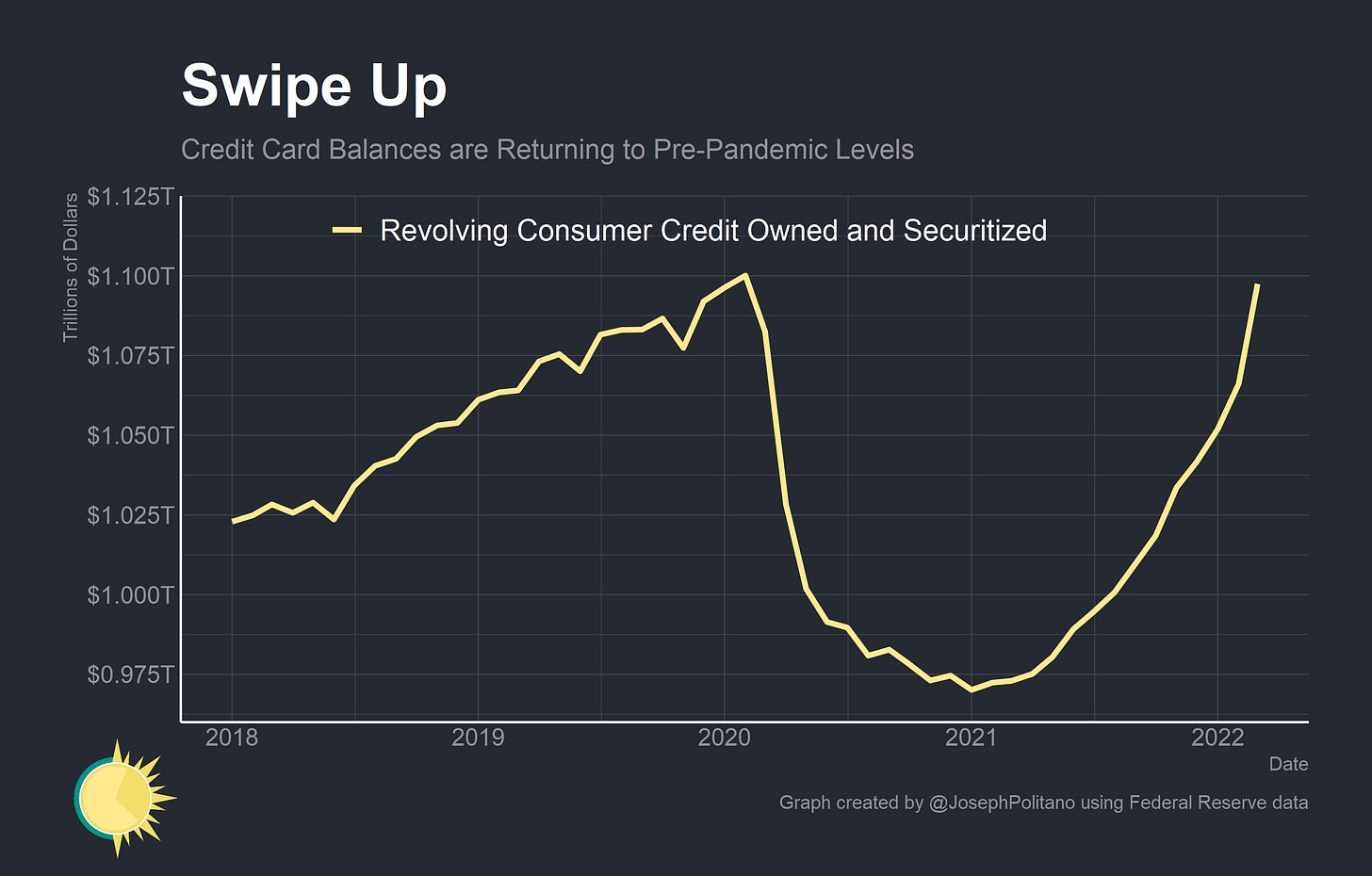

Finally, consumer credit growth has been extremely strong in the second half of 2021 and first half of 2022. Credit card balances are up $125 Billion in just the last year alone. That’s good in the sense that aggressive borrowing partially reflected a return to pre-pandemic consumption patterns and consumer credit growth usually occurs during periods of rapid economic expansion. However, it is bad in the sense that rising prices (especially of groceries and other essentials) are likely biting into household budgets and forcing many lower-income people into debt to maintain consumption standards.

Conclusions

Back in January, I laid out my thoughts on the future path of excess savings as such:

While most of the excess savings is held by high-income Americans, who do not have a particularly high marginal propensity to consume, I do think that high income earners will consume more of their excess savings than they would under a traditional increase in wealth. For one, high-income households have been stockpiling extremely liquid financial assets, an indication that they may only be waiting for a good opportunity to spend their money. For two, historical episodes of excess savings (like the post-WWII era) have seen a slow but steady drawdown of excess savings over the following 5-10 years. For three, polling from earlier this year showed that consumers intended to spend down some of their excess savings, and personal consumption expenditures have already exceeded their pre-COVID trend.

Generally, that trend has borne out over the last 6 months. Excess savings have decreased, driven by high-income households spending more (and being taxed on their income/capital gains). However, I underappreciated the downside risks to lower and middle-income household’s balance sheets—risks that have only intensified since then.

The good news on that front is, despite an appreciable slowdown in the labor market, employment levels and wage growth remain strong. Most Americans’ most valuable asset is their job, and that is especially true of lower and middle-income Americans. Without a job, however, they would not be able to rely on excess savings.

Readers who are familiar with the National Income and Product Accounts will note that I condensed “personal taxes” and “contributions for government social insurance” into simply “taxes” and condensed “personal income receipts on assets” and “proprietors' income” into “capital/proprietor’s income”. This was done to make the chart cleaner and improve data communication. “Personal current transfer payments” (transfers to the government and the rest of the world) were also excluded due to their negligible effect on excess savings.

This is the greatness that you’re meant to do.

Impressive work.