Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 17,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

It has been a turbulent year in global energy markets, to say the least. Oil, gasoline, and electricity prices started the year high and only moved higher after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. American oil production still lags behind its pre-pandemic peak while US natural gas is working to buffer Europe from acute shortages. Gasoline and oil prices may have already fallen significantly from their summer peaks, but the refinery capacity shortage is still biting and global oil markets remain in a precarious position.

At this critical juncture, the US will be laying down one of the tools it used to stabilize energy markets—oil releases from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). The SPR was built for just the kind of conflict-induced energy shortage that America found itself in after the Russian invasion—and policymakers used the SPR to buffer global markets from the aftershock of lost Russian energy supply. This year’s drawdown was the fastest and largest in the SPR’s history, and it is soon officially coming to a close.

This puts America at an energy turning point—it is essentially handing marginal supply responses back from the government to a combination of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the global private sector. The White House is keeping the option open for further SPR releases if prices get out of hand again, but the shift is still critical—amidst relatively high prices, OPEC is announcing production cuts and US oil output is stagnating. So how well can global energy markets handle being back on their own?

Putting the Strategy in Strategic

Conceptually, it’s best to treat the SPR as discretionary supply, not extra inventory. Private sector inventories respond to current and expected supply and demand conditions, being drawn down or filled up based on prices and expected future prices. The distinction between private inventories and the SPR lies in the latter’s strategic nature—refills and drawdowns are about maximizing perceived American economic security and prosperity, not strictly maximizing profits. There are, of course, elements of partisanship and politics in SPR releases, especially the kind of token signaling releases that usually occur after gas price spikes. But I think (especially in the current environment) those partisan concerns have been overemphasized—the SPR was built for the kind of large short-term energy supply disruptions that international conflicts tend to cause and a President of any party would have almost certainly used SPR releases in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

So let’s treat the SPR as the necessary, discretionary supply it is. Releases are therefore best thought of as a supplement to domestic oil production—and a significant one at that. Net SPR withdrawals added nearly one million barrels per day to American oil production—an approximately 8.5% increase in total output. That discretionary supply is going to be fully removed by the end of this year and the Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) short-term economic outlook does not forecast production net SPR withdrawals to reach its 2022 peak by the end of 2023.

Indeed, we have already started seeing the first signs of production slowdowns in the second half of this year. The EIA’s modeled weekly oil output data shows production essentially stagnating over the last five months. Baker-Hughes rig counts have also stagnated, and the supply of drilled-but-uncompleted wells is dropping fast, both of which suggest comparatively limited short-term production growth.

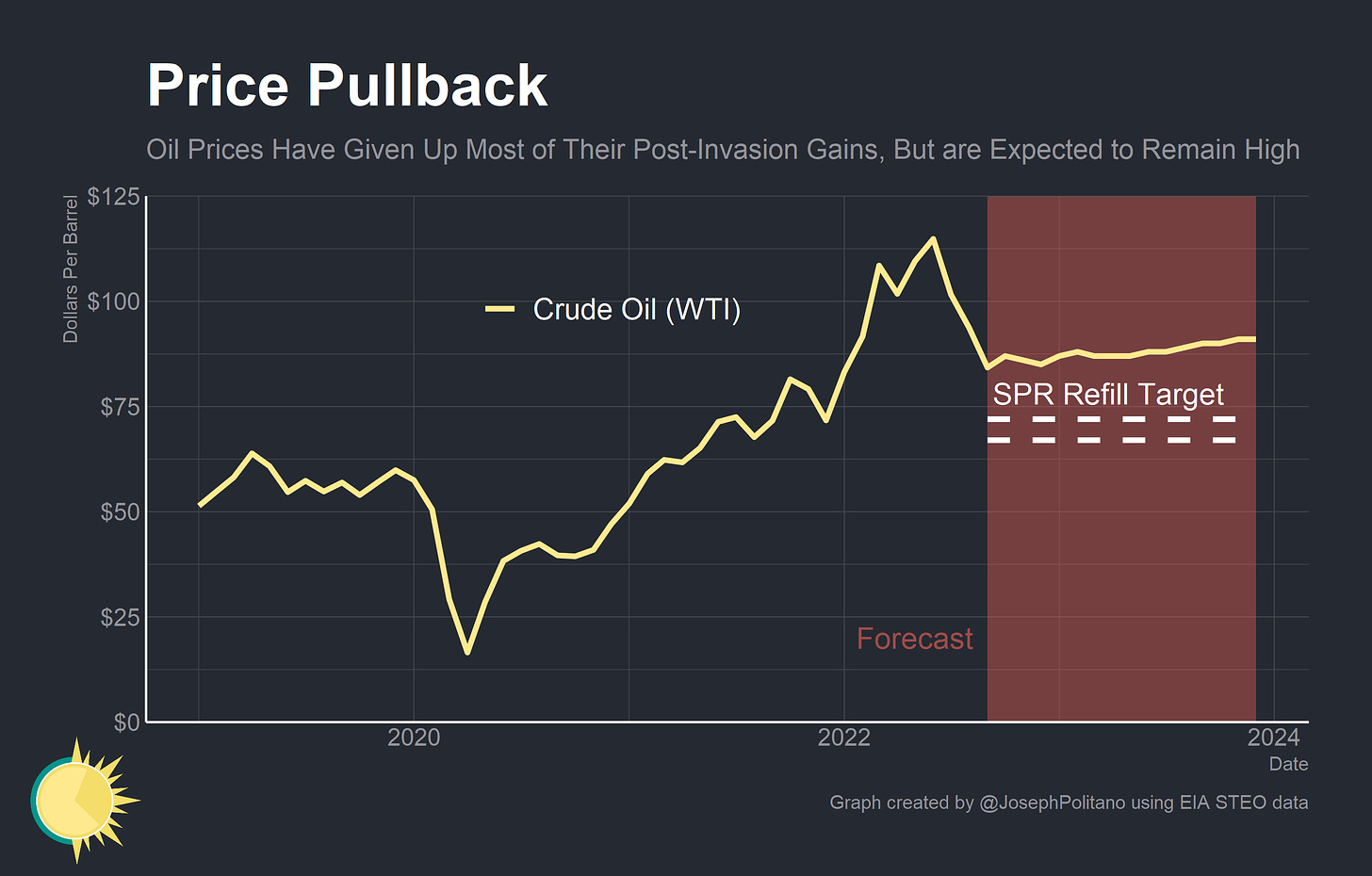

That may be partially why the EIA is forecasting slight price increases over the next year. That forecast is more bullish on oil prices than the current state of the futures market, but neither EIA nor the futures market currently expects crude oil to sink below the White House’s announced $67-$72 target for refilling the SPR in 2023. That’s partly why, aside from the recovery of exchange barrels, the SPR’s inventory is not expected to be refilled at all next year.

Futures prices—which aren’t strictly forecasts, but are significantly informed by price forecasts and expectations—don’t show crude oil prices reaching the SPR’s refill target until essentially mid-2024. The futures curve is also extremely backwardated—in other words, spot prices are higher than futures prices and futures prices get lower the farther forward in time. It’s another important signal of how tight current oil markets are that companies can’t draw on inventories in sufficient quantities to reduce backwardation—and that they expect prices to decline only as more production comes online.

But there is an important way that the SPR can utilize today’s backwardated oil curve to its advantage. The Department of Energy is officially moving forward with a rule “allowing fixed-price forward purchases of crude oil to replenish the SPR at lower prices than the barrels sold, while providing certainty to industry that will help encourage short-term production.” This is a version of the proposal from think-tank Employ America that I have discussed previously and, in conjunction with the implementation of provisions from the Inflation Reduction Act, it could help alleviate some of America’s existing energy shortage.

The pitch is that by making fixed-price purchases of crude along the futures curve the SPR will reduce the volatility and price risk that is partially holding back domestic investment. That should encourage domestic production, reduce the risk that energy shortages compound recession risks, and net the government a reasonable profit. It’s another way the SPR is helping shield domestic energy markets through a critical turning point.

Global Energy Supply

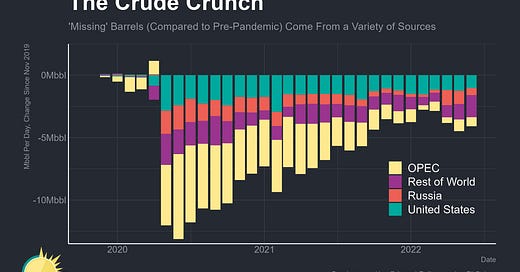

America, of course, isn’t the only energy producer with a downturn in production compared to before the pandemic. Global crude output as of June was more than 4 Million barrels per day below its immediate pre-COVID levels, with significant chunks of those missing barrels coming from the US, OPEC, and Russia. The SPR release functionally compensates for only 1/4 of that gap—hence the extremely high prices of earlier this year. Plus, surplus capacity abroad seems to remain in short supply.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.