America's Industrial Transition

US Manufacturing is Slowing—Excluding the Record Spending on Semiconductor Fabricators and Tech Manufacturing Plants

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 27,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

After the initial shock of the pandemic, there was a massive surge in demand for goods across the US. Homebound consumers increased spending on groceries, bought more personal electronics, renovated their homes, and kept ordering things online. That caused clogging at America’s major ports, significant inflation across goods supply chains, a surge in American manufacturing output, and a rapid recovery in industrial employment.

However, that initial shock was nearly three years ago at this point—consumers are no longer homebound, have been spending much more money on services, and have diminished need for manufactured goods given all the demand pulled forward during the early pandemic. Supply chains, although still suffering, have received some time to heal—and real consumption of goods has stagnated for nearly two full years.

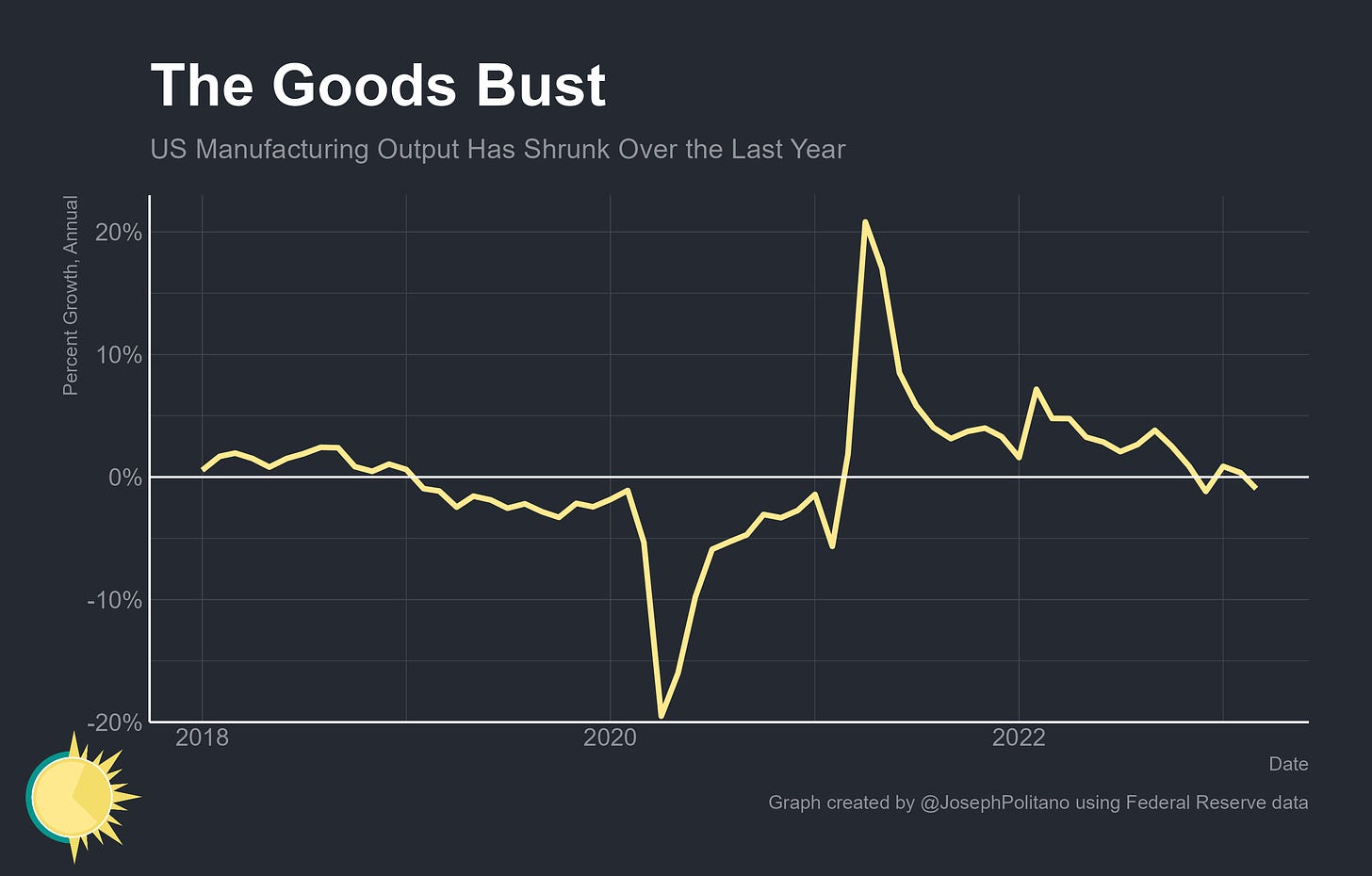

Those conditions have caused a major slowdown in the goods-related sectors of America’s economy—output is stalling, hiring has slowed down, and capital expenditure plans are being wound back. Even related industries like warehousing and truck transportation are struggling. Growth in US manufacturing production has declined substantially, with output actually shrinking slightly over the last year while still remaining below 2018 levels in aggregate.

There is, however, one bright spot in the manufacturing slowdown—an investment boom in the high-tech manufacturing industries receiving billions in investments from the Federal government after the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Construction of new semiconductor fabricators, especially in the American Southwest, now constitutes a massive share of overall US industrial investment and has contributed to a bump in construction employment over the last several months. As of March, employment in the computer/electronic and semiconductor manufacturing industries was higher than at any point in the decade preceding 2022.

The optimistic read right now is that things are stabilizing after years of extremely high demand; today’s cycle might resemble the limited industrial slowdown of the mid-2010s except with an increase in physical capacity investment thanks to government stimulus efforts. The pessimistic read is that investment spending won’t be enough to compensate for a potential further fall in consumption demand—especially if a recession occurs as the Fed tries to get inflation under control.

The CHIPS Act Is Supporting US Industrial Investment

America used to be a leader in semiconductors—the Department of Defense was a large and consistent customer and director for the nascent industry during the early parts of the Cold War, and even as the private sector became the industry’s predominant customer America maintained a large market presence. But then rising international competitors—Japan in the 1980s and then Taiwan, South Korea, and China soon after—started swiftly eating into US market share, a process that was only accelerated by the 2001 and 2008 recessions. Falling market share meant less ability to learn by doing and naturally innovate during the production process, less demand for the kind of specially-trained workers needed for these facilities, and fewer opportunities for governments to invest in chip research outside of Universities. The situation for cutting-edge chips deteriorated even more, with US firms and domestic fabs essentially falling out of the competition entirely. Therefore the CHIPS Act represents a gamble that a massive injection of federal spending will once again kickstart the US semiconductor industry—with security benefits and economic spillovers that more than compensate for the costs.

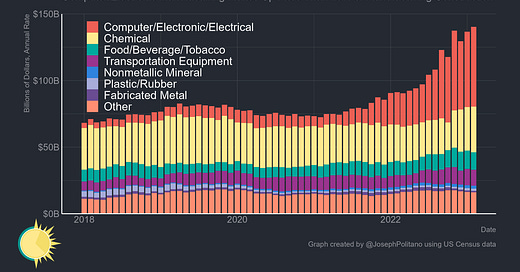

One thing is for sure so far—the CHIPS Act has already massively buoyed US semiconductor/computer/electronic manufacturing investment and by extension overall US manufacturing construction. At an annualized rate, more than $140B is now being plowed into new domestic manufacturing facilities with more than $60B going to new computer/electronic/electrical manufacturing alone. To put that number in perspective, the current combined value of all medical and educational construction in the US is only about $65B, and the total for all office buildings is only about $80B. Outside of CHIPS-related industries, nominal manufacturing construction spending has grown only marginally—which amidst elevated inflation almost certainly means that real US manufacturing construction would have been on the decline in the absence of CHIPS.

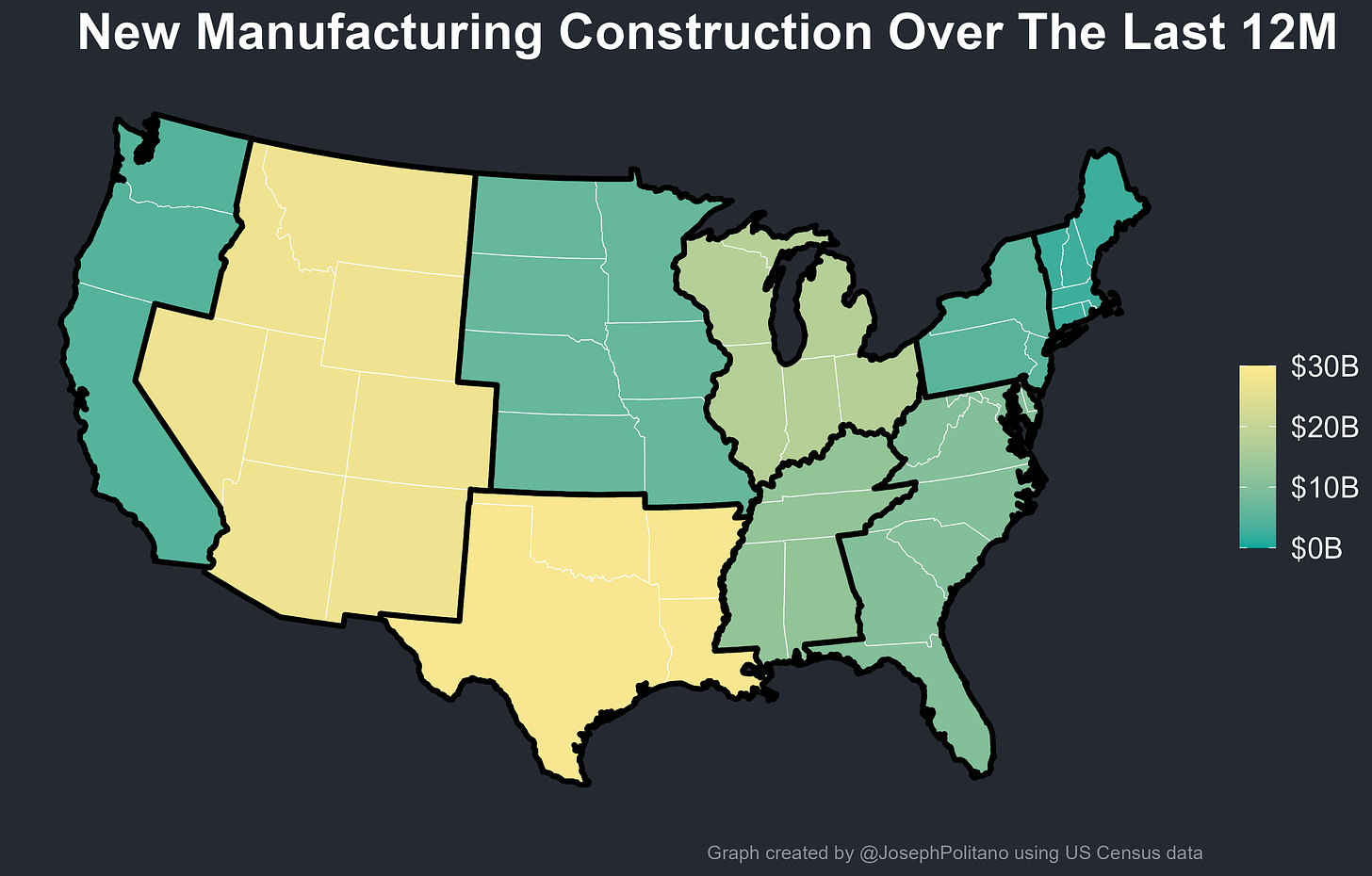

Of the construction actually put into place over the last year, nearly half of it went to just two Southwestern census regions—the West South Central region (mostly Texas) and the Mountain region (mostly Arizona and New Mexico). Construction in East North Central—Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin, America’s traditional industrial heartland—has also picked up to $17B over the last twelve months as chip projects and new electric vehicle plants begin to take shape. Still, the two sunbelt regions are undoubtedly the fastest-growing centers for American manufacturing—since 2017, they have composed nearly 45% of total new manufacturing construction spending, and Texas alone added 54,000 manufacturing jobs last year.

It’s not just construction that’s being boosted either—real fixed investment in industrial equipment remains above pre-pandemic highs even as it has marginally fallen over the last year, nominal new orders for capital goods from domestic manufacturers likewise remain near record highs, and employment in industrial building construction jumped at the start of this year. Still, as much as these new investments are extremely massive stimulus efforts directed at America’s manufacturing sector, they remain a small part of the country’s existing industrial capacity—the rest of which is doing extremely poorly by comparison.

America’s Current Industrial Base is Slowing Down

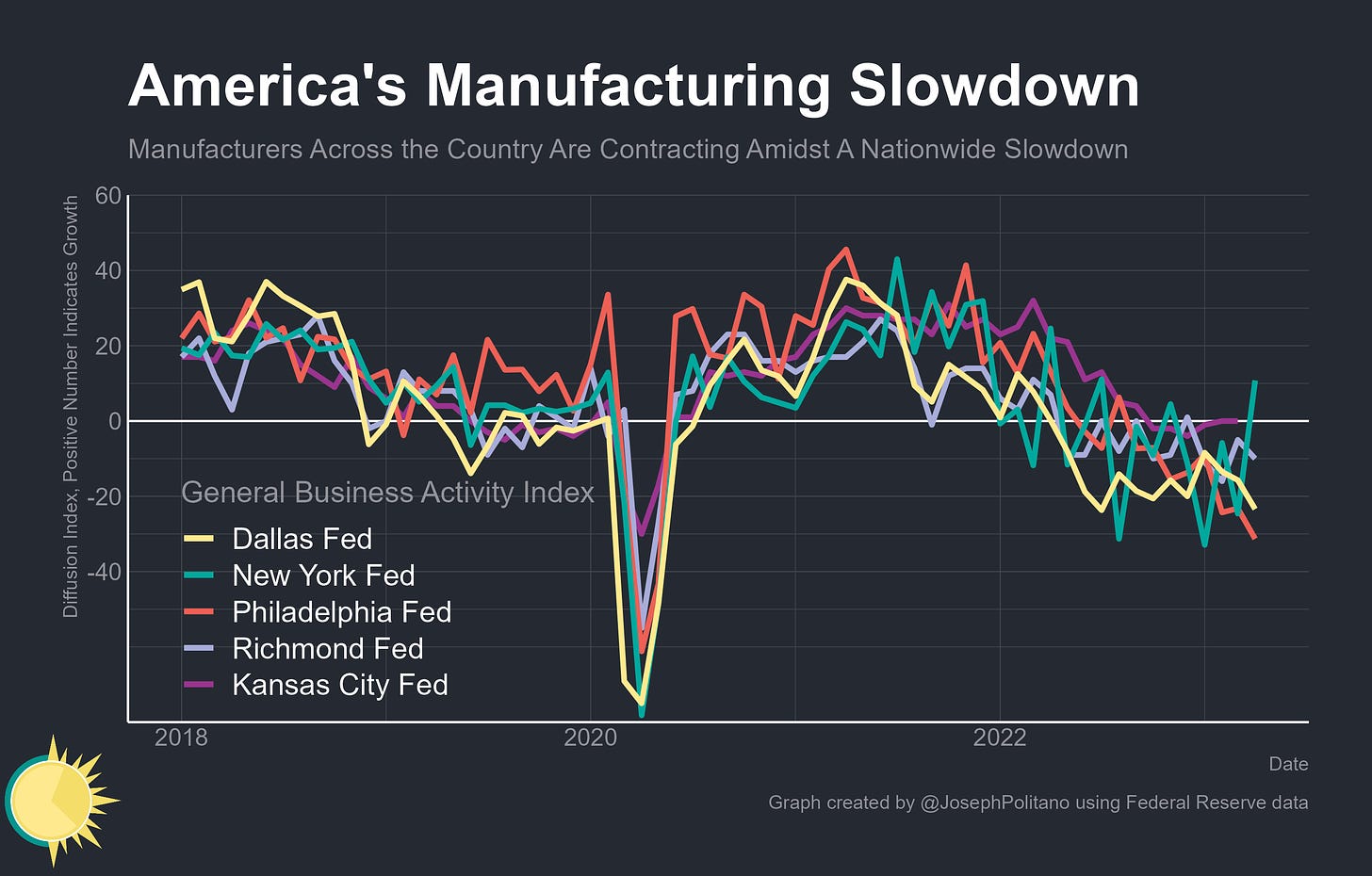

For the bulk of 2022 and all of 2023, American manufacturers have seen conditions progressively worsen—across the 5 regional Fed manufacturing surveys, monthly expansion has been a rarity, especially in recent prints. More and more plants are reporting struggles with low demand (instead of materials or labor shortages) as consumer spending weakens, and firms have dramatically slowed down their hiring plans. Indeed, there are already strong signs of fading manufacturing labor demand—a possible harbinger of further pain coming for the industry and its workers—and baseline manufacturing strength is likely lower than headline figures would suggest.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.