America's Manufacturing Productivity Problem

US Manufacturing Productivity Has Been Stagnant for 15 Years. Industrial Policy Must Aim to Fix That.

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 42,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Over the last several years, America’s experience with geopolitical conflict, acute shortages, and high inflation has dramatically increased its focus on securing supply chains through industrial policy. The scale of government intervention in the manufacturing sector has thus grown significantly—with the strategic use of tariffs, subsidies, sanctions, export restrictions, and more all on the rise. Nowhere is this industrial policy push exemplified more than in the current surge in manufacturing construction spending, which hit another all-time high in March as money from the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act turbocharged domestic investment.

Yet recent industrial policy has thus far been unable to solve American manufacturing’s greatest fundamental problem—its complete lack of productivity growth. Today, US factories produce just as much per hour worked as they did in 2007, despite the tectonic technological and economic shifts of the last 17 years. Productivity growth is always nothing short of fundamental to manufacturing success, but it is especially essential for a wealthy economy like the US where the high wages and ample opportunities in other sectors necessitate a large output per worker for American manufacturing to remain competitive.

The recent lack of productivity growth therefore makes it difficult or impossible for America to compete in many key industries where it seeks to regain dominance—while also contributing to the inability to enter nascent high-tech goods markets, the decline of communities dependent on manufacturing, and the still-wide labor market gaps between workers with and without a college education. So far, today’s revamped focus on industrial policy has done nothing to change US manufacturing’s lack of productivity growth—and industrial policy will fail unless it can break American industry out of that stagnation.

American Industry’s Lost Decades

There are multiple ways to measure economic productivity, but in practice it’s usually best to look from the perspective of labor productivity—the total real output produced divided by the total number of hours worked in the industry. That measure squeezes a lot of disparate concepts together—the factories, equipment, & other fixed assets available per worker (capital intensity), the production processes, research, and innovation that makes assets more efficient (capital productivity), the shifting skills, education, and age of the workforce (labor composition), plus much more. Yet by virtue of being a highly-aggregated measure, it ends up being a more robust indicator that had historically maintained a more consistent trend before the last couple of decades.

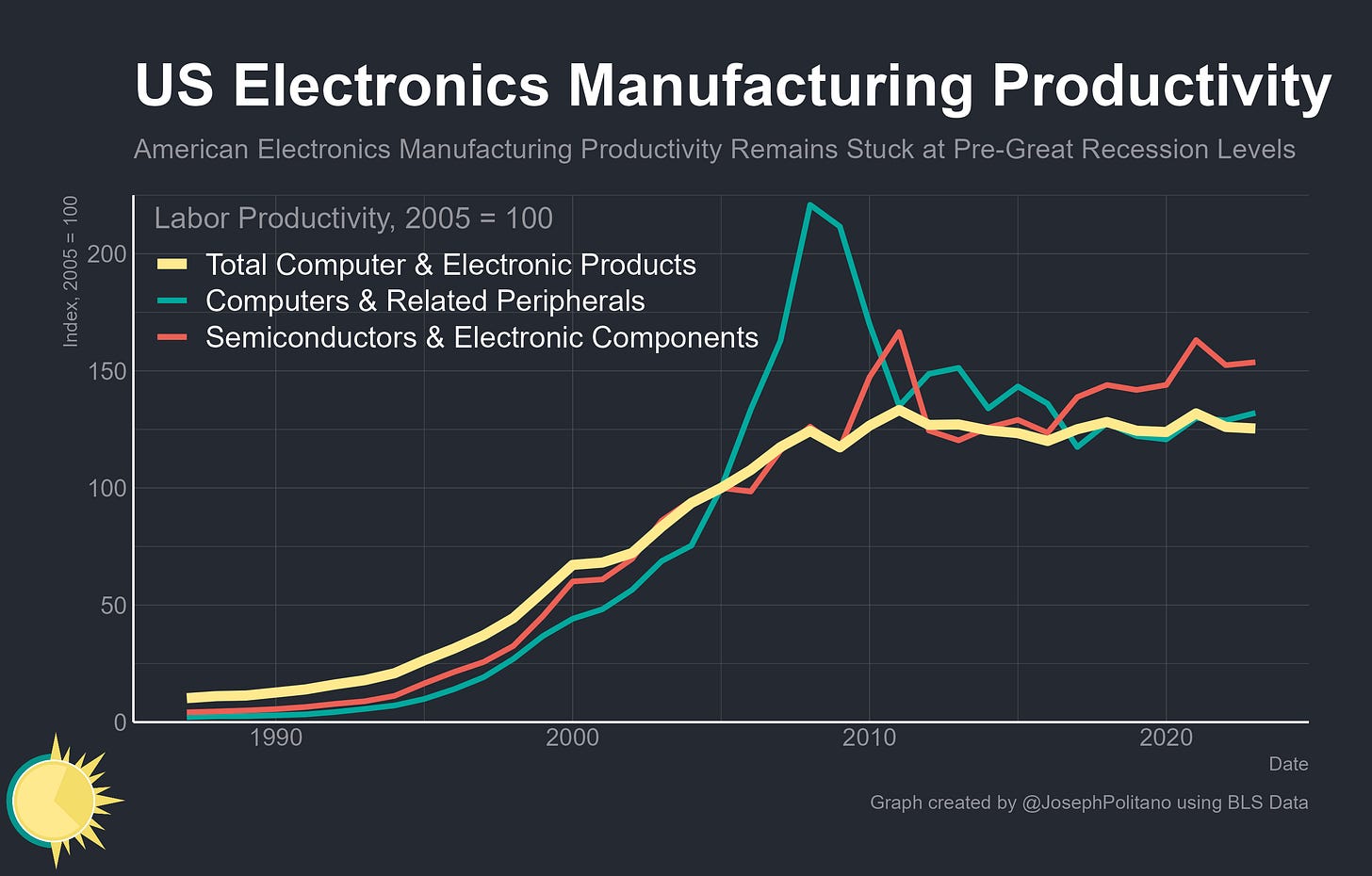

Indeed, the US had seen manufacturing labor productivity growth of 96% between 1987 and 2005 but since then productivity has only grown by a meager 7.8%. The computer and electronics manufacturing industry serves as a primary driver and great case study—from 1987 to 2005 labor productivity in the sector skyrocketed by more than 870%, yet the subsequent decline of America’s electronics manufacturing industry and its loss of productivity growth also explains roughly 40% of the decline of overall manufacturing productivity growth during the 2010s. The first place to investigate the death of US manufacturing productivity is thus in the highest-tech sector that previously drove the largest chunk of labor productivity gains.

Between the early 1990s and 2000s, the computer and electronics industry made up a large and growing part of all US manufacturing shipments—but its share plunged in the wake of the 2001 recession and only kept declining after 2008. Computer and electronics manufacturing employment went from roughly 1.9M in 2001 to about 1.1M in 2011, a level it has hovered around ever since, while total real sectoral output remains 8.3% below its 2008 peak even 15 years later. The recessions meant American industry had, overall, moved down the value chain—a higher share of the national manufacturing base was now made up of lower-tech sectors as global electronics manufacturing moved abroad, especially to East Asia.

In addition to the slowing aggregate productivity caused by high-tech digital manufacturing moving abroad, productivity growth within the remaining US electronics industry slowed down substantially post-2000 and completely ground to a halt after 2008. Per hour worked, American semiconductor foundries, electronics factories, and computer manufacturers produce just as much as they did before the Great Recession despite the massive increase in US tech consumption since then. Productivity growth in the semiconductor and electronic component subsector slowed significantly, and computer productivity cratered as its output dropped nearly 50% between 2008 and 2011. Those dynamics of tech manufacturing were exemplary of the problems faced throughout the US manufacturing sector—even though no other major subsector came close to the productivity growth of electronics manufacturing in the late 1990s, virtually all had robust positive productivity growth through 2005 that has slowed considerably or even reversed since.

Take the US car industry—from 1987 to 2005 output per hour worked increased by 71%, but from 2005-2022 it rose by only 16%. Productivity initially spiked in the wake of the Great Recession but for all the wrong reasons—layoffs were happening faster than output was declining. Then productivity was largely stagnant post-auto-bailout and as the broader economy recovered through the late 2010s. Recently, the industry even saw a decline in productivity post-COVID as the semiconductor shortage and other supply constraints hampered car production.

Or take electrical equipment and appliance manufacturing, where labor productivity rose 78% between 1987 and 2005 but subsequently fell by more than 9% between 2005 and today.

Or look at the chemical industry where overall productivity has slid downward for more than a decade, led by a collapse in pharmaceutical productivity as agricultural and basic chemical manufacturing productivity stagnate. In fact, you could repeat this exercise for nearly all US manufacturing subsectors—this is an endemic, multicausal problem, not isolated to one area but widespread throughout America’s industrial base

The Roots of America’s Manufacturing Productivity Problem

A large part of America’s manufacturing productivity problem is the cross-industry compositional effect discussed earlier—post 2001 and 2008, high-tech fast-productivity-growth industries were increasingly offshored and thus represented a smaller share of US manufacturing. Perhaps more importantly, that shift has been coupled with a lack of manufacturing business investment—the overall capital intensity of American manufacturing, which represents the relative amount of fixed assets used in production, slowed in the 2000s and nearly flatlined in the 2010s. In other words, if you think about the amount of factories, equipment, vehicles, etc used per manufacturing worker, that number has stopped growing due to the underinvestment in new manufacturing equipment and structures throughout the last 20 years. Some subsectors, like the chemical industry, have seen more steady capital intensity growth, while electronics experienced a slowdown and electrical/vehicle manufacturing saw outright stagnation.

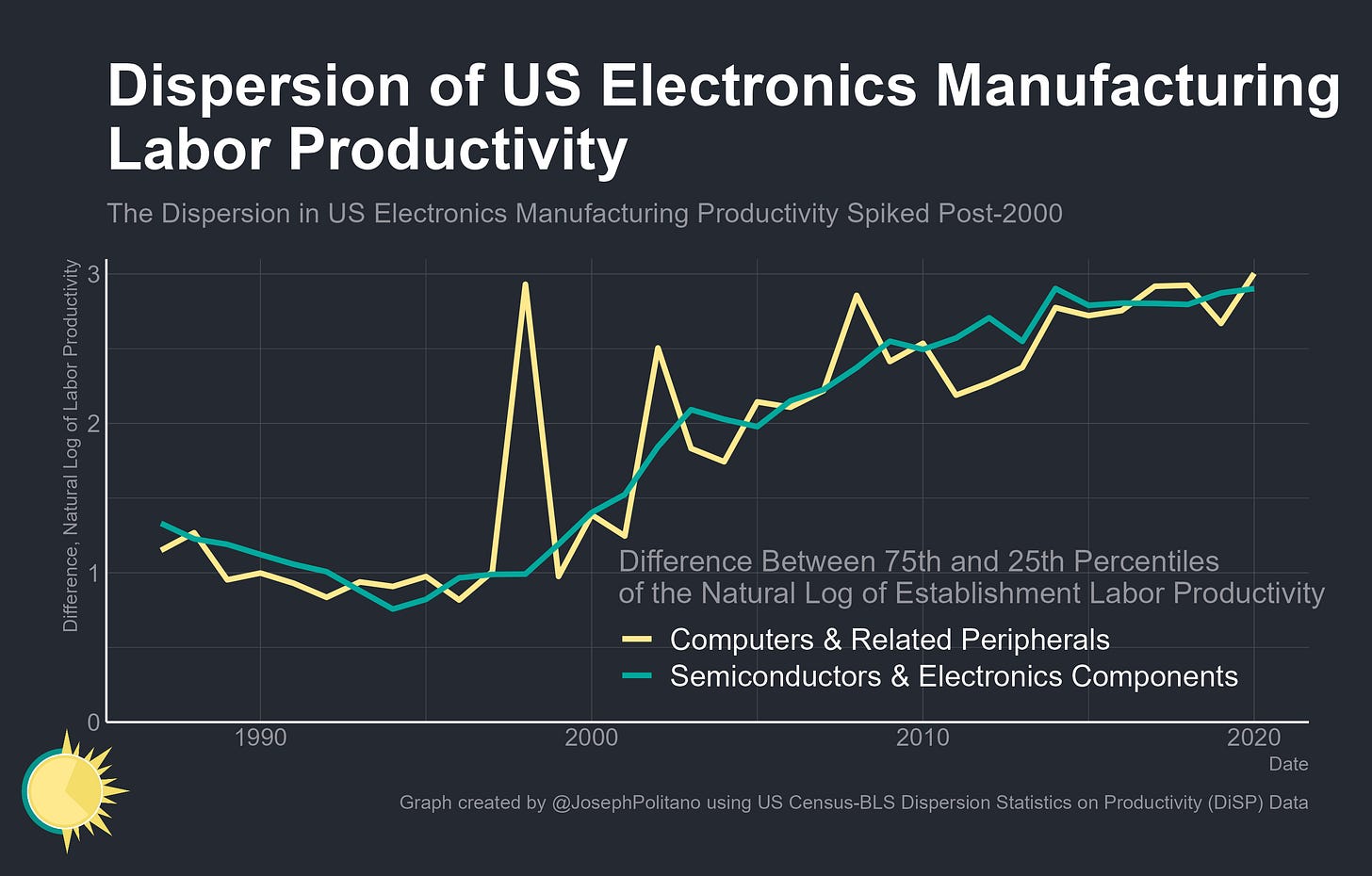

Using data on the dispersion of productivity across factories and other establishments, it also becomes clear that the gap between the most and least productive US manufacturers increased considerably since the turn of the millennium. This gap is most stark in previously high-productivity-growth sectors like electronics—a small subset of factories saw substantial (if slower) productivity gains through the 2000s and 2010s while most establishments saw stagnating or declining productivity. Part of this is due to a weakening of manufacturing sector R&D growth, which has slowed the pace of innovation, but it also reflects a broader problem where the diffusion of innovation within industries had slowed down—a small subset of companies remained at the technological frontier, where a much larger share fell behind.

Contributing to that lack of innovation and technological dissipation, the robust industry startup ecosystem that used to exist has also rapidly dissipated, with the manufacturing firm entry rate shrinking for decades. High-tech subsectors like electronics have seen the fastest decline in their startup rate, going from well above the manufacturing sector average to decidedly below it. These figures even arguably understate how large the damage is—the number of manufacturing firms has shrunk, the share of firms in high-tech industries has shrunk, and the share of high-tech manufacturing firms that were recent startups has shrunk. Even among the smaller number of new companies, recent births tended to stay smaller and grow slower than their older peers did at their age.

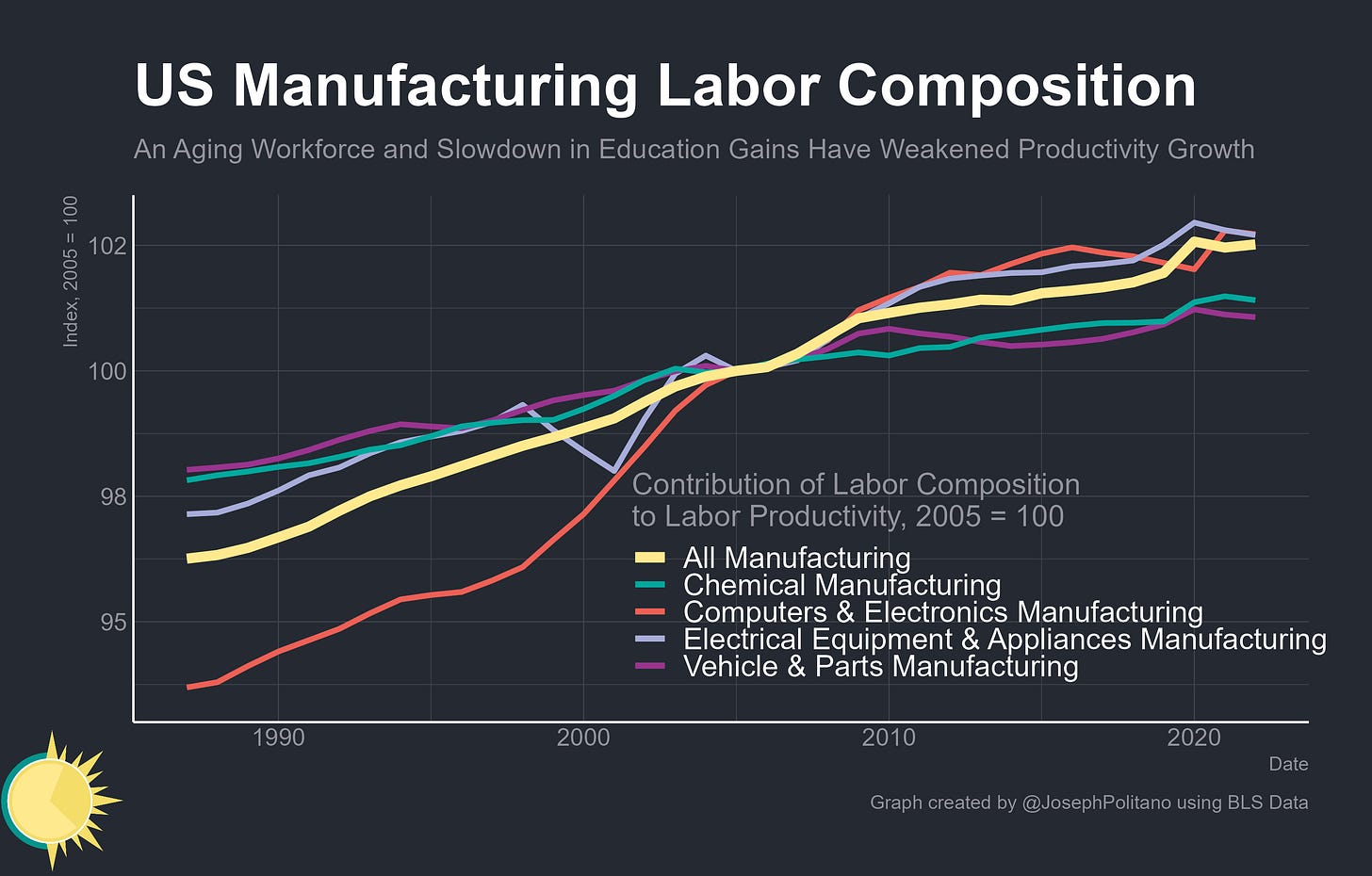

Another smaller factor in manufacturing productivity stagnation has come from the workforce—upskilling and rising educational attainment used to be larger drivers of productivity growth, especially in electronics, but have slowed down considerably. Increasingly, the best opportunities for workers with a college degree are outside of manufacturing and America’s remaining industrial workforce has aged significantly. That means the labor force skills and experience necessary for a highly efficient manufacturing industry have steadily atrophied over the last 20 years. Combined, all of this has served to keep American manufacturing productivity growth low for decades.

The Past & Present of Industrial Policy

America’s recent bout of industrial policy will likely increase measured manufacturing productivity in the near term, even if only by shifting the composition of output away from legacy sectors and towards more cutting-edge areas like semiconductors. Yet within prioritized sectors, recent policy efforts have been generally unsuccessful at rejuvenating productivity growth. Protectionist trade policies have been perhaps the strongest in primary metal manufacturing—which includes the steel, iron, and aluminum industries that enjoyed heavy tariff expansions starting in 2018—yet labor productivity in the sector has dropped, not risen, over the last few years and is now at some of the lowest levels since the early 2000s. The famous US Steel Corporation has fallen so far behind that Japan’s Nippon Steel is now looking to take it over—and the US government is looking to block the sale despite the fact America’s steel industry could learn a lot from its more efficient Japanese counterpart. That pattern is seen in other industries supported by recent US industrial policy, especially motor vehicles, where labor productivity growth has been weak and American companies continue to fall behind.

However, like it or not the US is politically committed to industrial policy in large part because it appears to be an electoral success. Pre-COVID trade wars caused economic damage to US manufacturing centers but bore fruit politically—and given the key role manufacturing hubs states like Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, and Pennsylvania will play in upcoming US elections protectionism and investment subsidies remain a political strategy pursued by both parties. Given that, what form should industrial policy take?

To the extent policy must show favoritism to key industries, they should be done for high-productivity and not low-productivity sectors. This sounds obvious on paper but is difficult in practice—existing domestic industries, which usually by definition are dated institutions, almost always have more political clout than emergent or foreign industries. Hence why so much of historic US industrial policy efforts have been focused on agribusiness, metals, and legacy motor vehicles instead of more modern manufacturing sectors. Some progress has certainly been made here, as the industries benefitting the most from recent legislation represent more cutting-edge electronics and cleantech sectors, but this shift must be maintained.

Where government subsidies and protectionism are deployed, they must also be coupled with efforts to encourage new firm entry and punish or cull firms that aren’t able to maintain productivity growth. Targets that overly prioritize employment over wage and output growth can be counterproductive here; the labor side of industrial policy should look to improve job-worker matches, upskill the existing US workforce, and attract international manufacturing talent rather than only adding jobs.

For industrial policy to be successful the aim must also be for the US to compete in, not hide from, international markets. That means attracting more foreign manufacturing investment after today’s subsidized construction surge will be critical, as is learning from more efficient European, Japanese, Korean, Taiwanese, and even Chinese firms in the industries where they lead. Trade restrictions, wherever implemented, should also be narrowly targeted to prevent a broad spiral of retaliatory trade conflicts and must take care not to increase the costs of intermediate inputs critical to downstream manufacturing sectors. If policymakers are serious about competing with Chinese industry they must also accept more cooperation and integration with non-Chinese supply chains and not simply retreat into widespread protectionism.

Conclusions

It’s also important to note that US productivity growth outside manufacturing has been strong post-COVID—aggregate output per hour worked has risen by 7.5% over the last four and a half years even as manufacturing-specific productivity is only up 1.3%. In fact, overall US productivity has grown faster than it did between 2015 and late 2019. That is exceptional news for the country—a policy success that stands in stark contrast to America’s weak post-2008 recovery and the weak post-COVID recoveries of many other high-income nations. It also highlights why, given the choice, you would always pick service sector productivity growth over manufacturing productivity growth simply because services are a much, much, larger share of modern economies.

Yet it makes some of the problems for industrial America even more pressing—advanced manufacturing sectors are struggling to compete for labor with highly-paid industries like finance and tech, and the manufacturing wage premium over even low-pay industries like leisure & hospitality is shrinking. Policies that aim to reallocate US jobs away from services and towards manufacturing now could also eat at productivity growth if they don’t also boost industrial efficiency or have positive knock-on effects. That’s a real risk in a more labor-supply-constrained environment; while US employment rates remain below historical peaks and peer-country averages, new factories are increasingly pulling labor from other sectors and not from unemployment as they did in the 2010s. The tradeoffs are harsher and the costs of mistakes are higher—which is why American industrial policy can’t succeed unless it reverses today’s stagnant manufacturing productivity.

Joseph, an excellent description of a serious issue. My question is, what type of impact has the financialization of the economy had on this problem.. CEO's are far more concerned about repaying shareholders and driving stock prices higher than building whatever product they are building. This seems to be a key driver behind the lack of investment, as well as the fact that companies continue to buy competitors rather than build out their own physical plant as evidenced by the dramatic reduction in the number of publicly listed companies.

Finally, one other concern has been the change in the composition of higher education efforts, with far fewer engineers being minted and many more degrees in less useful majors. Consider how many fewer plumbers and electricians are around as since the 1990's there has been such a strong drive to get HS grads to go to college rather than into a trade. college is not for everyone, and I fear many have degrees, and the accompanying debt, without having acquired the requisite skills to be successful.

Alas, these are long term problems and it is not clear to me that government policies, which have a long history of failure across virtually every subject, are going to solve them without serious unforeseen consequences.

Hi, Joseph, It's a good article, but could I translate this article into Korean and upload it separately on my blog, citing the source?