America's Missing Empty Homes

Housing Vacancy Rates are at Historic Lows—Signaling an Extremely Supply-Constrained Market

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 35,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

If you had shown up at any used car dealership over the last two years you may have noticed a startling amount of asphalt exposed to sunlight—dealer inventories collapsed during the pandemic, leading to a shortage in vehicles available for purchase and a surplus of parking spaces. Massive shortfalls in motor vehicle production driven by shortages of semiconductors and other electronic items had cut off the supply of new vehicles to the market. Without new vehicles to buy, those who had an older car were unable to trade theirs in or upgrade to a new vehicle, and thus used car dealerships were cut off from their primary source of supply. Prices for preowned cars spiked in early 2021 and remain 40% above pre-pandemic levels even as the market cools and inventory slowly returns. In a sense, the share of vacant vehicles available to lease or purchase plummeted—and that lack of vacancies signaled a tight, supply-constrained market with rapidly rising prices.

If that sounds familiar, it also could easily describe the pandemic-era housing market. Homeowner vacancy rates have dropped to the lowest levels on record last quarter, a long structural trend that was amplified by the pandemic-era boom in demand for suburban living space and the recent surge in mortgage rates. Yet while a lot of hay has been made about the plummeting inventory of for-sale homes, the ongoing decline in rental vacancies has been just as stark and much less reported on. In 2022, the rental vacancy rate fell to the lowest level since 1984 before rebounding a bit this year—but keep in mind that today’s 6.3% rental vacancy rate still means the average unit only spends roughly 3 weeks on the market before a lease is signed.

Yet what, precisely, do we mean by a “vacancy rate”? The economic definition is a bit different than the colloquial definition—instead of looking at the total share of units that are currently unoccupied, the rental and homeowner vacancy rates look only at what percent of empty renter and owner-occupied units are available for rent or purchase. So an unoccupied unit undergoing repairs is not part of the vacancy rate, but once repairs are completed and that unit becomes available to rent it is part of the vacancy rate.

However, detailed data on occupancy rates also allow us to easily derive estimates of “gross vacancy rates”—the raw share of housing that is currently unoccupied, regardless of reason (for clarity’s sake I will be referring to this as “unoccupied housing rates” from here on out). That includes units for sale or rent but also vacant units kept for seasonal or occasional use, units needing or undergoing repairs, those kept for family or personal reasons, and all other unoccupied units. America’s unoccupied housing rate has also been dipping consistently for years—and has now fallen to the lowest levels since the turn of the millennium. Just as with cars, that lack of vacancies signals a tight, supply-constrained market with rapidly rising prices.

The depth of that housing shortage is massive—keep in mind that 95% of new apartments and 90% of new condos are rented out or sold within a year of completion, meaning increasing unoccupied housing rates will require substantial amounts of construction. Just to get rates back up to the 12% pre-pandemic level would require adding 2.7 million new housing units—more than the entire housing stock of the state of Maryland or more than 1.5 years of construction at 2022 rates—and leaving them all empty. Assume half occupancy and America needs 6.2 million new units—more than currently exist in Pennsylvania. If you assume that 75% of units will get filled on net then America needs more than 18 million additional housing units—roughly as many as exist in California and Washington state combined. Actual construction stood at only 1.4 million in the first half of 2023, failing to keep up with demand and leading to further declines in unoccupied housing rates—in other words, the structural shortage of housing is keeping prices high and vacancies down.

Understanding Why a House Can Be Empty

Not all of America’s empty homes are created equal, however—they are located in different regions are are unoccupied for different reasons, making detailed vacancy data invaluable. The largest major source of unoccupied housing are those for seasonal use—heavily concentrated outside major metros in America’s ski resorts and beach towns—clocking in just ahead of the number of housing units available for rent. Then is housing for occasional use—weekend homes and the pied-à-terres of the wealthy—followed by housing currently in use by a family that usually lives elsewhere (classified as “unoccupied” to prevent double-counting), then units that haven’t been moved into yet, and then the small share of units for sale.

However, there is also the mass of units vacant for “other” reasons—roughly 2.5% of the nation’s housing stock—for which we only have detailed data going back to 2012. Here, units held vacant for personal/family reasons make up a plurality, followed by those needing or undergoing repairs, then the catch-all “extended absence & other” categories, plus the small amount of housing in foreclosure or other legal disputes, held for storage, held in preparation for entering the market, abandoned, or used only for specific purposes.

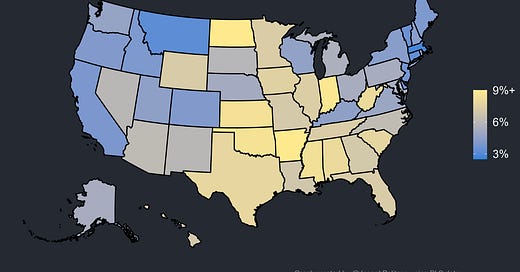

That’s a lot to take in, but the general trend is that the supply of ready-to-move-into vacant units has dwindled significantly over the last decade—especially post-pandemic. The share of units for sale, for rent, used seasonally, used occasionally, in foreclosure, held for storage, or abandoned have all fallen as housing markets continue tightening. The shortfall in supply compared to demand is also inducing owners to bring less-market-ready units back into service—relative to the number of units needing repair, the number of units undergoing repairs has surged. Yet vacancies also have a massive geographic component—concentrated in cheaper areas outside major cities and in the metro areas with more housing construction—and that has reshaped US internal migration and housing markets during the pandemic.

The Geography of Housing Vacancies & Construction

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.