America's New Business Boom

Americans Have Been Forming New Businesses at Record Rates. But is This a Real Startup Boom—or Just The Rise of Gig Work and Side Hustles?

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 38,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Nearly one and a half years ago, I left my 9-5 job and decided to officially turn this newsletter into its own business. That was an intensely personal decision, but it was also an intensely macroeconomic one—I would not have had the financial runway to start this company had I not been able to save much of the unemployment benefits and other early-pandemic-era stimulus I received, nor would I have had the confidence to walk away from a stable job were it not for the knowledge that the labor market remained tight and someone else would likely hire me if this venture failed.

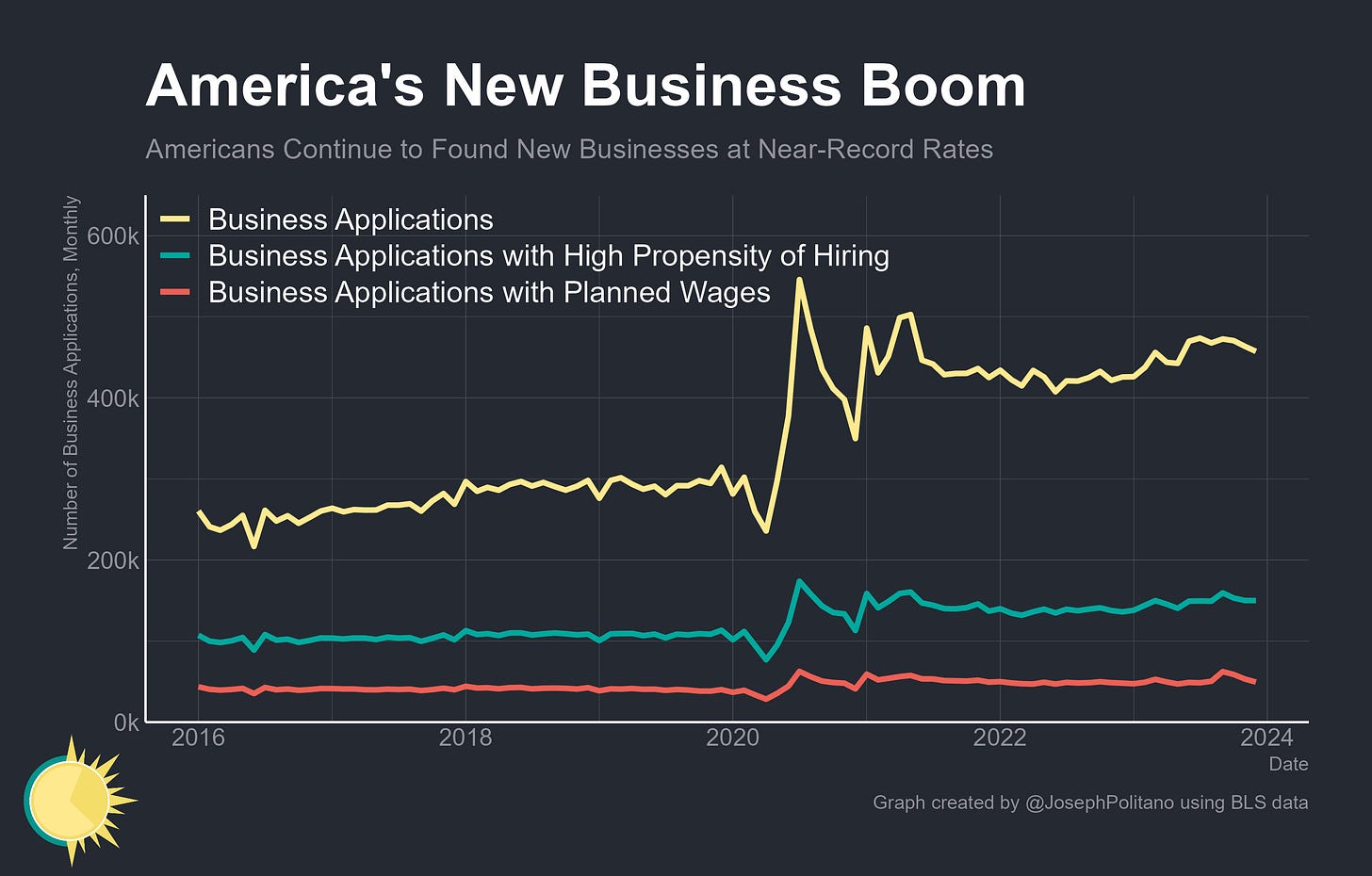

Those macroeconomic factors meant I was not alone in taking the leap to start my own company—shortly after the onset of COVID, Americans began forming new businesses at record-high rates, and they have hardly let up since. In December, 457k business applications were filed in the US, 143k more than at the same time in 2019. Of those, 150k were identified as having a high propensity of hiring due to their application characteristics or industry category and another 49k explicitly indicated they planned to start paying workers.

Within the surge in business formations, the most common industry was retail trade, followed by professional services amidst the work-from-home revolution and construction firms that boomed amidst rapid housing price growth. Applications for transportation & warehousing startups—encompassing the gig, ridesharing, and delivery ecosystem of Uber/Doordash but also Amazon Flex, independent truckers, and much more—doubled by mid-2021 but have steadily declined since. Yet the boom in business formation has occurred across virtually the entire economy, with all major industries (bar mining) setting new records for monthly applications at some point since 2020.

But just looking at applications leaves a key question unanswered—how important are these new businesses? Starting a small store on Etsy as a side hustle, while nice, is not the same economically as opening up a full-sized downtown shop. Nor is temporarily working for Ubereats while in between jobs the same as buying an 18-wheeler and starting your own independent trucking business. Yet all of these paths could start with a business application, and a plethora of digital services have made that legal process of incorporating easier than ever before. Plus, incorporation could just have been used to access government small-business support efforts like the Paycheck Protection Program. How much of the rise in business applications is signal—and how much is noise?

Until recently, it’s been impossible to say for sure—new businesses are almost by definition hard to track, as people may apply to incorporate well before they actually begin operations and only file their earnings the following year when tax season rolls around. Then it can take even longer before new firms become fully integrated into the regular data-collection processes of government statistical agencies. That means we are only now getting the information necessary to paint a full picture of the magnitude and effects of America’s COVID-era new business boom.

The good news is that the rise in business applications has been followed by a significant increase in actual company formation and new business hiring throughout the US. Plus, that boom in firm creation has been coupled with a nationwide rise in entrepreneurship and self-employment, one that goes well beyond just the growth of the gig economy. The bad news is that the new business boom now appears to be slowing down somewhat—alongside the rest of the US labor market.

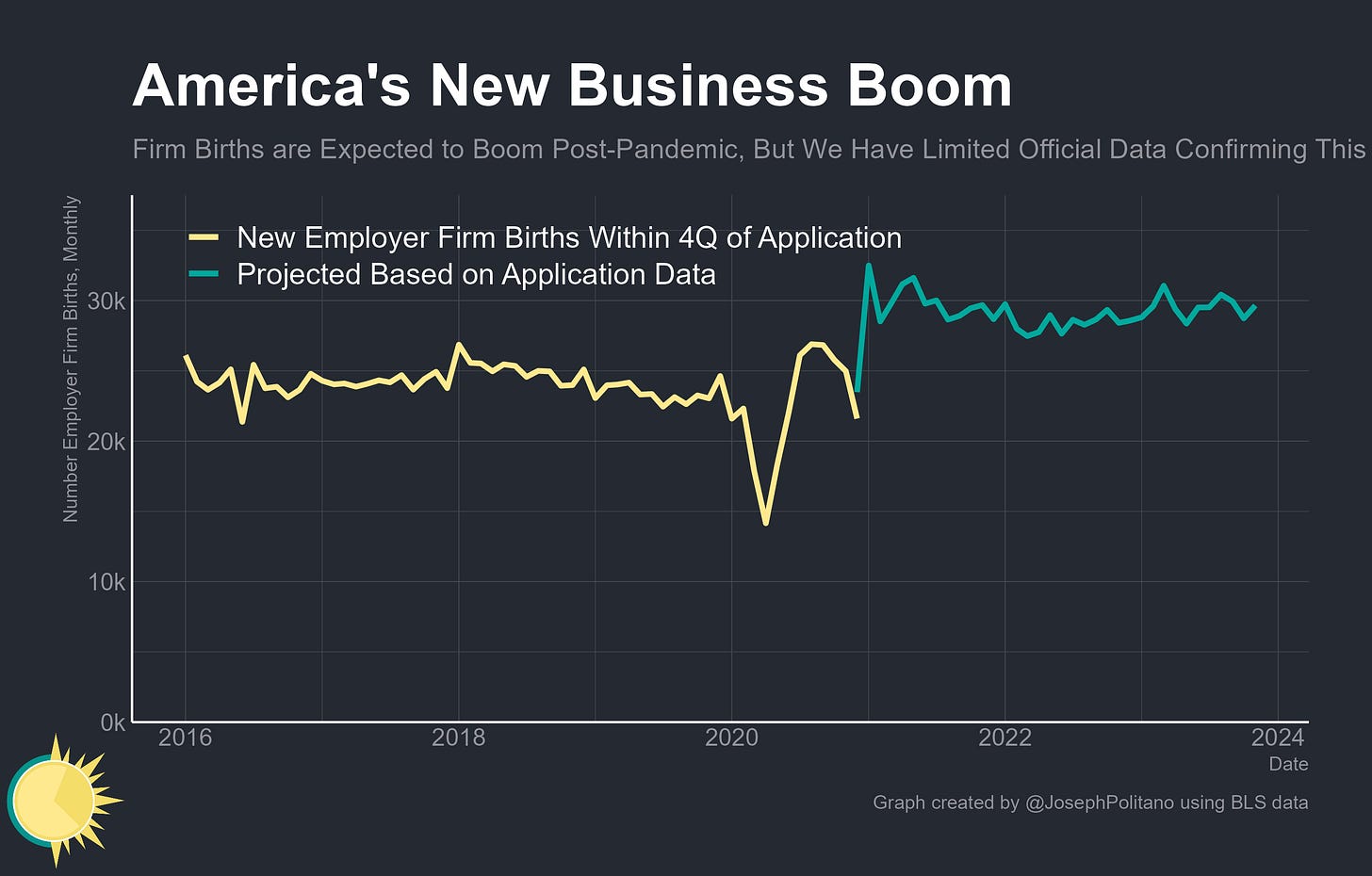

The Baby Business Boom

As mentioned earlier, statistics on business dynamics come out with a substantial lag—the US Census Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics are based primarily on corporate tax filings alongside other administrative data and can thus only track new companies nearly three years after they begin operations. That means even in 2024 we only have data on firm births through 2021—and therefore the most recent business applications for which we can reliably track outcomes are those made in 2020. The data we do have makes it clear there was a substantial uptick in employer firm births (the number of newly formed companies that hired employees) in late 2020 and early 2021 based on applications filed in 2020. Beyond that, we have only the projections based on application data alone, although those suggest a more durable ongoing rise in employer business formations.

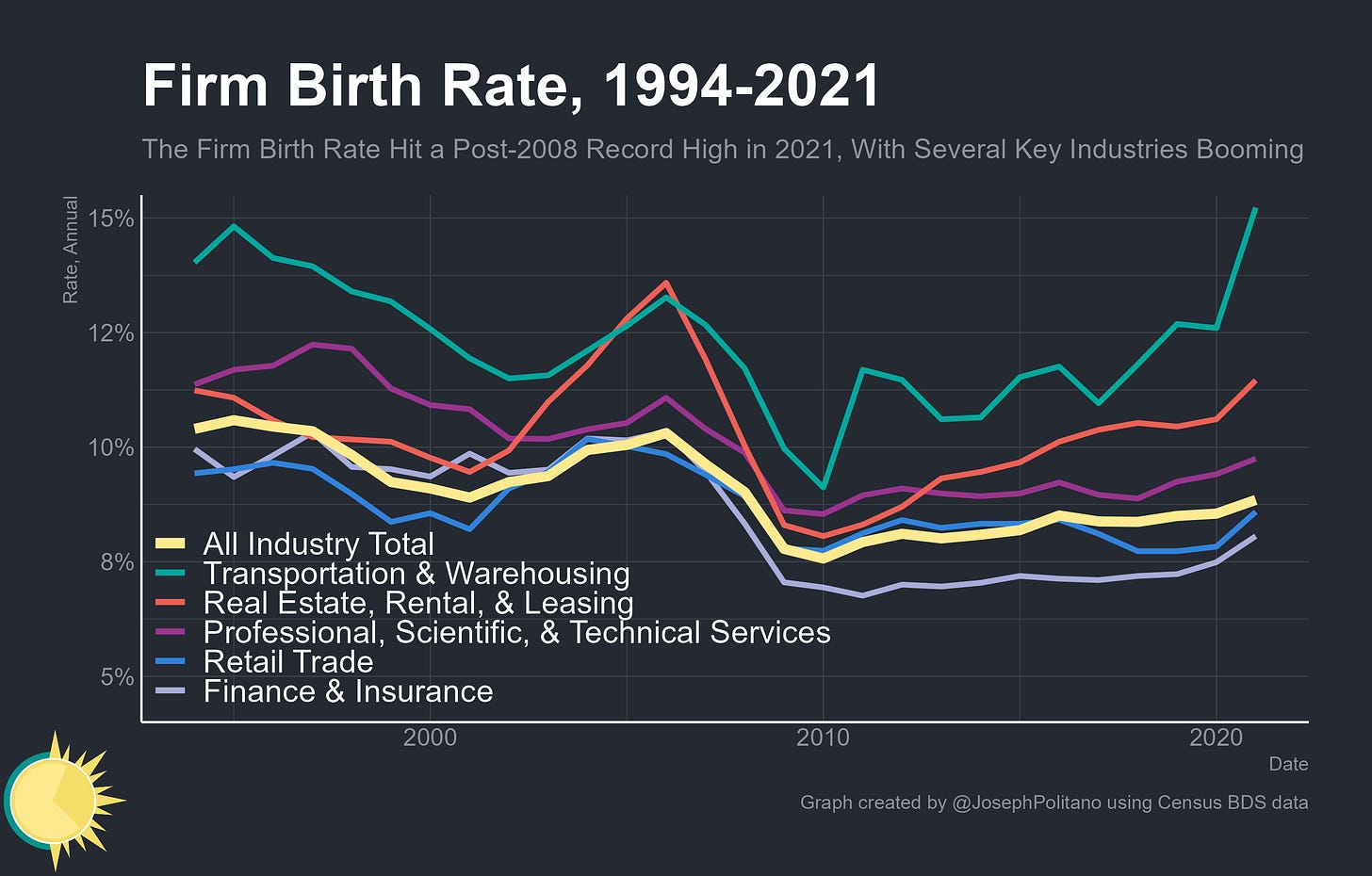

Pulling back to just the complete data through 2021, the firm birth rate officially rose to a post-2008 record high, hitting 8.85%, while corporate formation in many industries grew even faster. Transportation and Warehousing saw a massive increase in firm births, driven in large part by new small-scale trucking firms, while retail trade, finance, real estate, and professional/scientific/technical services all saw lower but still substantial increases. This surge in business formation has roughly matched the surge in applications across industries, but critically it has also matched the application boom geographically, especially as it relates to work-from-home shifting economic activity from the downtowns of city centers to their suburbs.

Super-small businesses represented an outsized share of those firm births in 2021—in fact, companies with only 1-4 employees represented a record 30.3% of all new-firm hiring for the 12 months after COVID’s onset in March 2020. Midsized and large startup hiring actually slowed down significantly compared over that same period, making super-small new businesses the only ones that saw accelerated hiring. Cratered job growth at food service & accommodation firms was a significant driver of the drop in hiring among midsized new businesses—one that was only partially countered by a rise in transportation & warehousing hiring. Meanwhile, professional/technical/scientific services, retail trade, construction, and real estate led the trend of rapid hiring at small startups.

Here, it’s important to introduce a distinction between the firms, which have been the subject of analysis so far, and business establishments. A firm is a legal entity (a startup, small business, publicly traded company, etc) and an establishment is a physical location where work occurs (a single factory, office, restaurant, etc). A major firm like Ford Motors will have many establishments including the corporate office in Michigan, research centers in California, and factories scattered throughout the United States—and can readily open and close these establishments as the company needs. Yet for the vast majority of companies, firm and establishment are functionally synonymous—the local coffee shop is one firm, and its singular location is its only establishment. That means there’s a significant overlap between firm and establishment births—in 2019 about 67% of new establishments and 50% of total new employment thereof came from firm creation. The key is that data on establishment births comes out at a significantly higher frequency, which means that by shifting the frame of analysis we can access much more up-to-date numbers on business openings.

Looking at the data on establishment births, it's clear that the rapid pace of firm creation seen in 2021 likely continued for much of 2022 and 2023. The establishment birth rate rose by one percentage point from 2019, hitting the highest levels since the 1990s in late 2021, and remained elevated well into the most recent data we have for early 2023. Establishment deaths also picked up rather strongly by mid-2022, although this bump is heavily influenced by the closure of healthcare services establishments that opened up during the early pandemic.

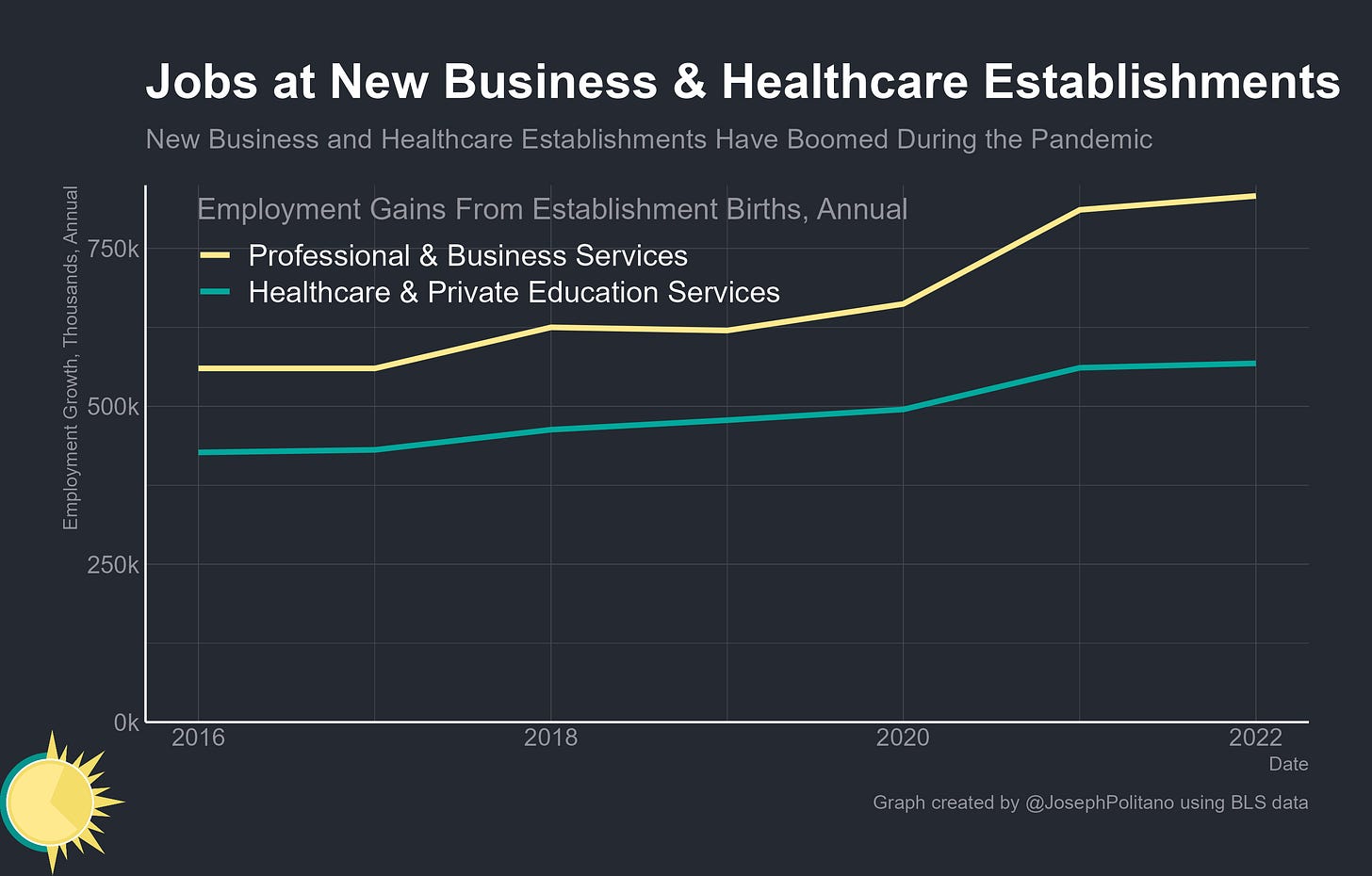

Overall, these new establishments also produced a hiring boom in the US, with employment gains at establishment births clocking in at 1.1M for Q4 2021—that’s the highest level since the early 2000s, though still well below what was normal for the late 1990s. Since that 2021 peak, the pace of hiring at new establishments has decelerated but remains well above pre-COVID levels, as in the most recent Q1 2023 data 944k new jobs were added at establishment births compared to the 812k added in Q1 2019.

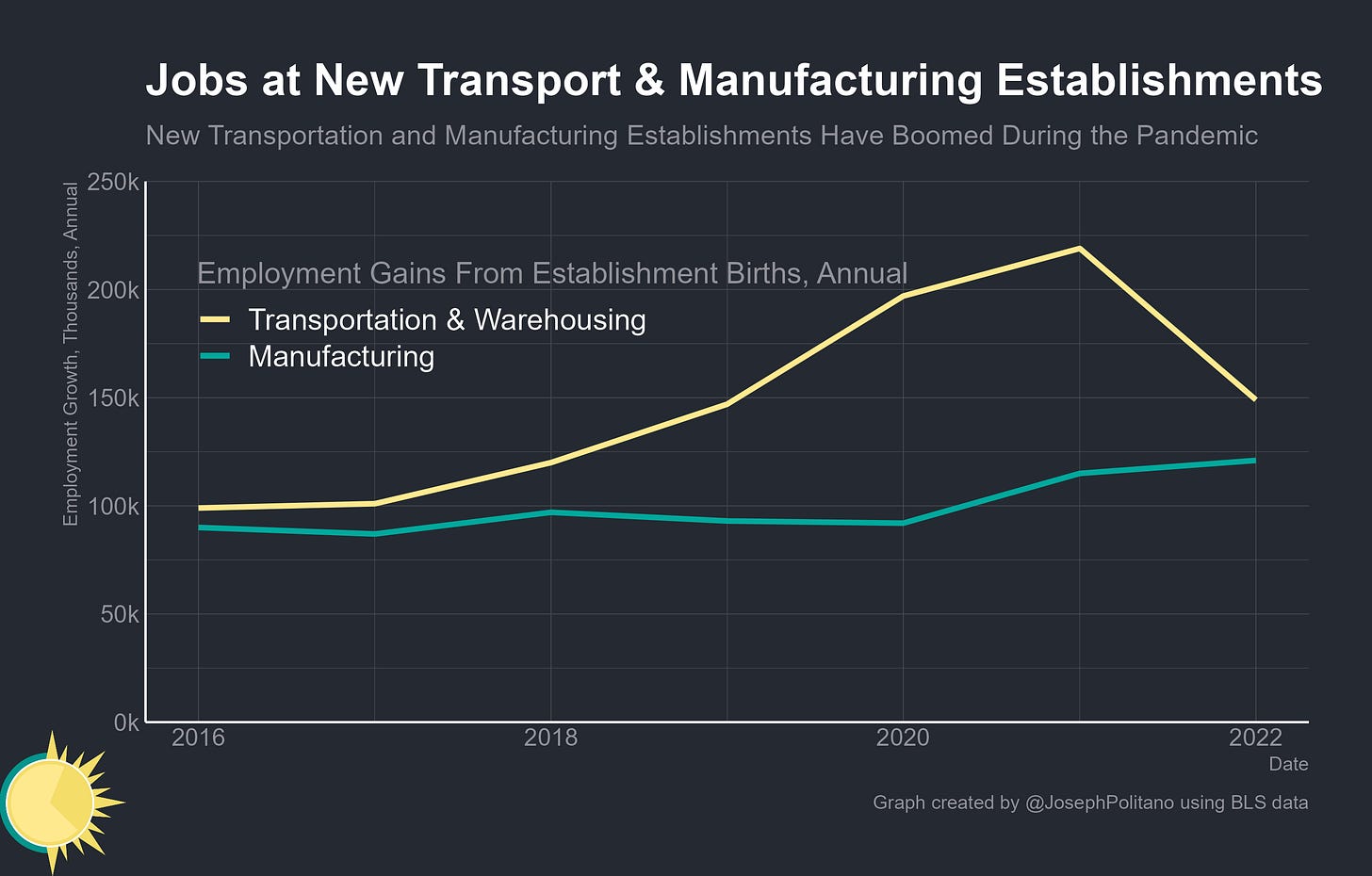

Hiring at establishment births in the transportation & warehousing industry rose to 219k in 2021, a 49% increase from 2019, and the fastest growth was in the warehousing & storage subsector where total employment gains at openings and reopenings rocketed up 140% between 2019 and 2021. The same figure was a more moderate but still substantial 27.5% increase in the truck transportation subsector and a 13% increase among couriers and messengers. Yet it was not the only part of industrial America that benefitted from the business formation boom—hiring at newly minted manufacturing establishments has also risen significantly since the start of the pandemic, hitting 121k in 2022, a 31.5% increase. Employment gains at opening chemical manufacturing establishments rose 49.6%, at computer/electronics manufacturers they rose 40.8%, and at fabricated metal manufacturers they rose 41% from 2019 to 2022.

Hiring at establishment births in white-collar professional & business services jobs rose by 1/3, and births in healthcare & private education services also rose by 18.8%. Jobs at opening/reopening private education services establishments unsurprisingly spiked to coincide with the start of the 2020/2021 school year, while within the healthcare industry, hiring at outpatient care services led the way. Virtually all subsectors of the business world saw accelerated hiring growth from new establishments, and complimentary industries like finance were also up significantly.

Finally, the tech industry also saw a surge in jobs at new establishments throughout most of the early pandemic, with opening computing infrastructure providers hiring at more than double their 2019 pace while opening web search portals and other information services increasing job gains by more than 50%. That historically rapid hiring has since slowed down significantly as the tech ecosystem and venture capital industry more broadly got hit hard in 2022 and 2023, but it still remains at or above normal pre-COVID levels.

The end result of this boom in new businesses has been that, for the first time in decades, the share of workers employed by young firms is rising. In 2022, 11.3% of jobs were in firms less than 5 years old, the highest share since 2010, and 8.6% of jobs were in firms 6-10 years old, the highest share since 2014.

Plus, in several key sectors, the rise in employment at young firms has been even more pronounced, with the share of jobs in companies below 5 years old or younger rising 1.3 percentage points in transportation/warehousing, 0.9 percentage points in Management and Information, and half a percentage point in Manufacturing. Of course, that still means the vast majority of Americans are employed at firms that are more than a decade old, highlighting just how prolonged the decline in business dynamism has been, but that trend is now finally beginning to be reversed.

America’s Self-Employment Boom

So we can confirm that the rise in business applications since the start of the pandemic has been followed by a substantial increase in real firm openings, with many of these new businesses hiring workers and expanding operations, and it is not just an artifact of side hustle growth. Yet it is also true that another contributor to the business application boom has been more people working for themselves out of necessity, convenience, and ambition—the self-employment rate, which had been on a secular decline since the mid-2000s, rebounded in 2020/2021 and remained a bit above pre-COVID levels in 2023. Critically, the long-run trend where a rising share of self-employment comes from those who have formed their own businesses has continued, with the incorporated share of self-employed workers reaching a record high of 68.7% in 2023, helping to drive up new business applications.

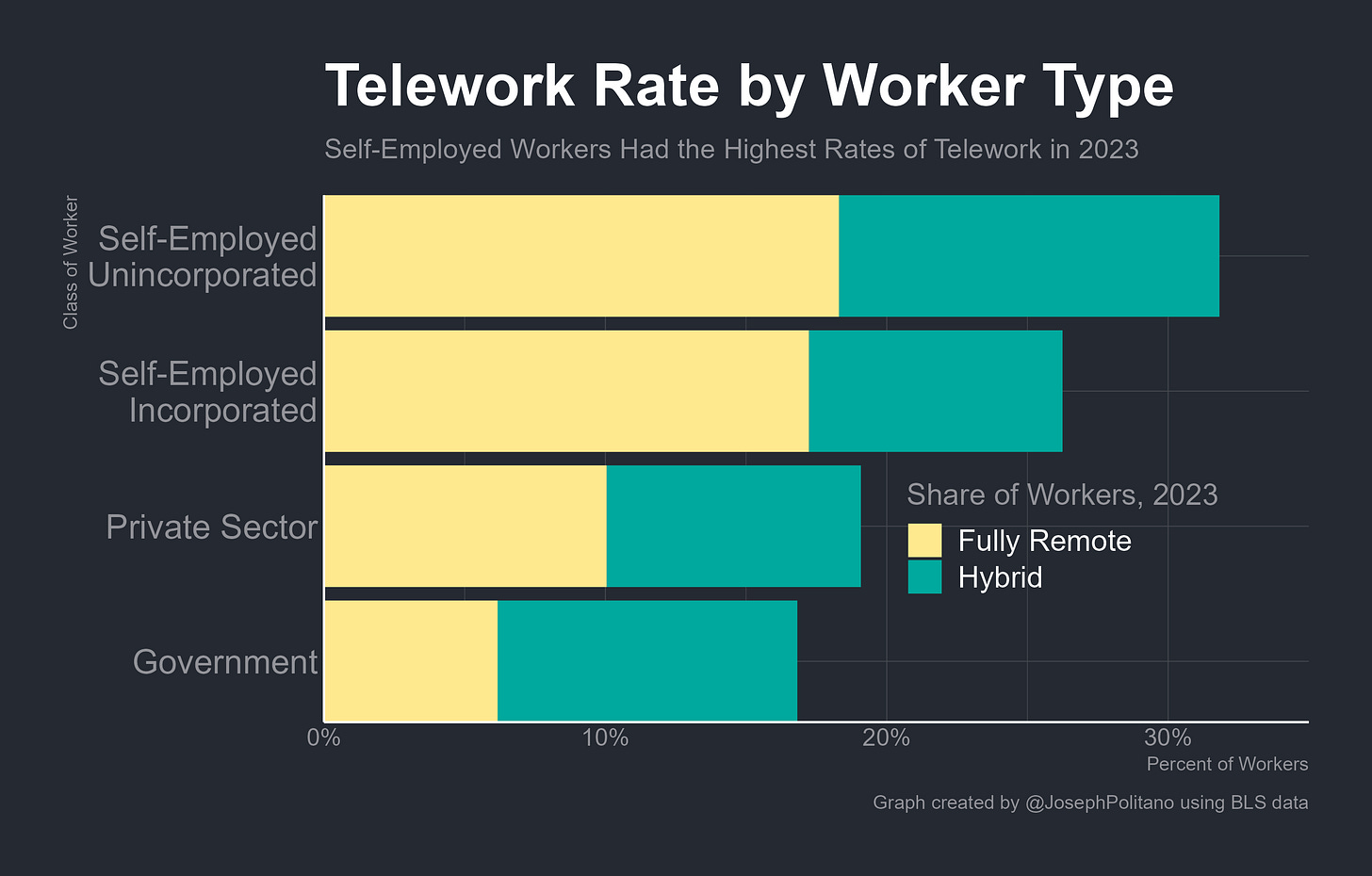

Unsurprisingly, remote work has played a major role in the recent growth of self-employment—2023 was the first time where we got comprehensive full-year telework data from the Current Population Survey, the same dataset used to calculate official employment and unemployment, and it showed that about 10.3% of workers were operating fully-remote on any given week and another 9.4% were splitting time between home and another workplace. The self-employed, especially the unincorporated, were far more likely than most to telework, with 17.7% being fully remote and another 10.9% operating hybrid. Telework also supported a remote-work entrepreneurship boom for parents, especially mothers—from 2019 to 2023 the share of women with young children (<6 years old) who were self-employed rose from 7.1% to 8.5% while for men with young children it rose from 10.6% to 11.7%.

As we’ve discussed before, the entrepreneurship and self-employment boom has also shown up on Americans’ balance sheets, with a record-high 1 in seven families now having some kind of direct business ownership. That dynamic has been particularly concentrated among groups that traditionally had low firm ownership rates—including the young, renters, Hispanic, and especially Black families. In fact, the surge in business applications has been stronger in ZIP codes with more Black residents, and self-employment income was the second-largest contributor to Black families’ real income gains from 2019-2022. Black and Hispanic workers also closed a significant amount of the self-employment gap, with the 1.6 percentage point increase in self-employment rates among Black men from 2019 to 2023 being particularly notable. That’s key given that the median value of direct business equity among US families is $90k, but the median value for self-employed workers hit a record-high $250k in 2022.

Finally, it’s worth discussing the gig economy itself. While the three most common industries for the unincorporated self-employed remain professional services, construction, and healthcare/education, the fastest-growing industry has been warehousing & transportation. In 2022, a record 687k unincorporated self-employed workers identified that their primary job was in the industry, a 25% increase from 2019 and an acceleration of a longstanding growth trend. Gig work growth has undoubtedly been a major part of this—the share of people receiving money from gig platforms on any given month rose from 2% pre-COVID to a peak of 3% in late 2021, and drivers are the most likely gig-worker occupation to have no other traditional job. Business applications in retail trade are also likely heavily influenced by side hustles, as the early COVID boom in nonstore retail business applications coincided with a rapid rise in income from “social commerce” platforms like Etsy. However, the gig economy has not been a primary driver of self-employment and business formations more recently—the share of people receiving money from gig platforms peaked in late 2021 but has trended down since, leading to a drop in the number of self-employed transportation workers in 2023. Falling work-from-home rates, slowing demand for takeout, and the recovery in formal employment all reduced overall gig work throughout 2022 and most of 2023, although recent growth in taxi demand and weakness in the formal labor market may soon be reversing the trend.

Conclusions

Indeed, the weaker labor market has broadly meant that America’s new business boom is slowing down—establishment entry rates have already fallen significantly since their 2022 peaks, and self-employment rates have now been on the decline for two years. Yet business application numbers have remained much stronger than they were pre-pandemic, suggesting that firm entry rates might durably break out of their long-run decline. Perhaps more importantly, the wave of businesses that were born in the early pandemic are now steadily maturing—their owners are becoming more knowledgeable about operating a business, their workers are adapting to new roles, and the businesses themselves are in many cases expanding. In other words, the increase in corporate formation during the early pandemic may finally be paying economic dividends in the form of higher growth today.

People lamenting the sclerotic productivity growth of the 2010s would often be quick to blame the lack of “creative destruction”—older, so-called “zombie firms”, entrenched by regulation and kept alive by low interest rates, had risen to encompass such a large share of the economy that they were strangling growth. This narrative was perhaps always a bit overdone—the fall in business dynamism was arguably more a downstream consequence of the too-tight macroeconomic policy that caused the 2001/2008 recessions rather than a driver of weak growth in it of itself. Yet the fact that business formation has boomed and post-COVID productivity growth has been robust at a time when corporate bankruptcies remain well below normal levels also suggests what was missing was creation more than destruction. New businesses keep pressure on the old ones even if they don’t kill them, and while small businesses themselves are rarely engines of productivity growth, each represents a roll of the dice on forming the next Amazon, Google, or Microsoft.

Still, despite the recent boom overall business and establishment formation rates remain well below historical norms, and even America’s vaunted tech industry has seen a steady decline in dynamism over the last two decades. Today’s new establishments also tend to be born smaller and stay smaller than their surviving historical peers, undercutting some of the effects of rising business formations. Overall, it’ll take years until today’s firm births reach adolescence and we can make more definitive statements on the effects of the recent new business boom. Yet the fact that so many Americans continue rolling the dice on their own companies is a sign of this economic recovery’s ongoing strength—and is only raising the chances some of them will eventually win big.

Do you share the belief that A.I. has boosted our productivity greatly and been a big factor in the U.S. economy’s continued growth? Technological factors cannot be understated in how an economy matures.

I had not remembered this tax change which seems to part of the reason for layoffs in tech world. Any thoughts?