America's Productivity Boom

US Productivity Growth is Booming and Massively Outshining its Peers—Here's How

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 47,000 people who read Apricitas!

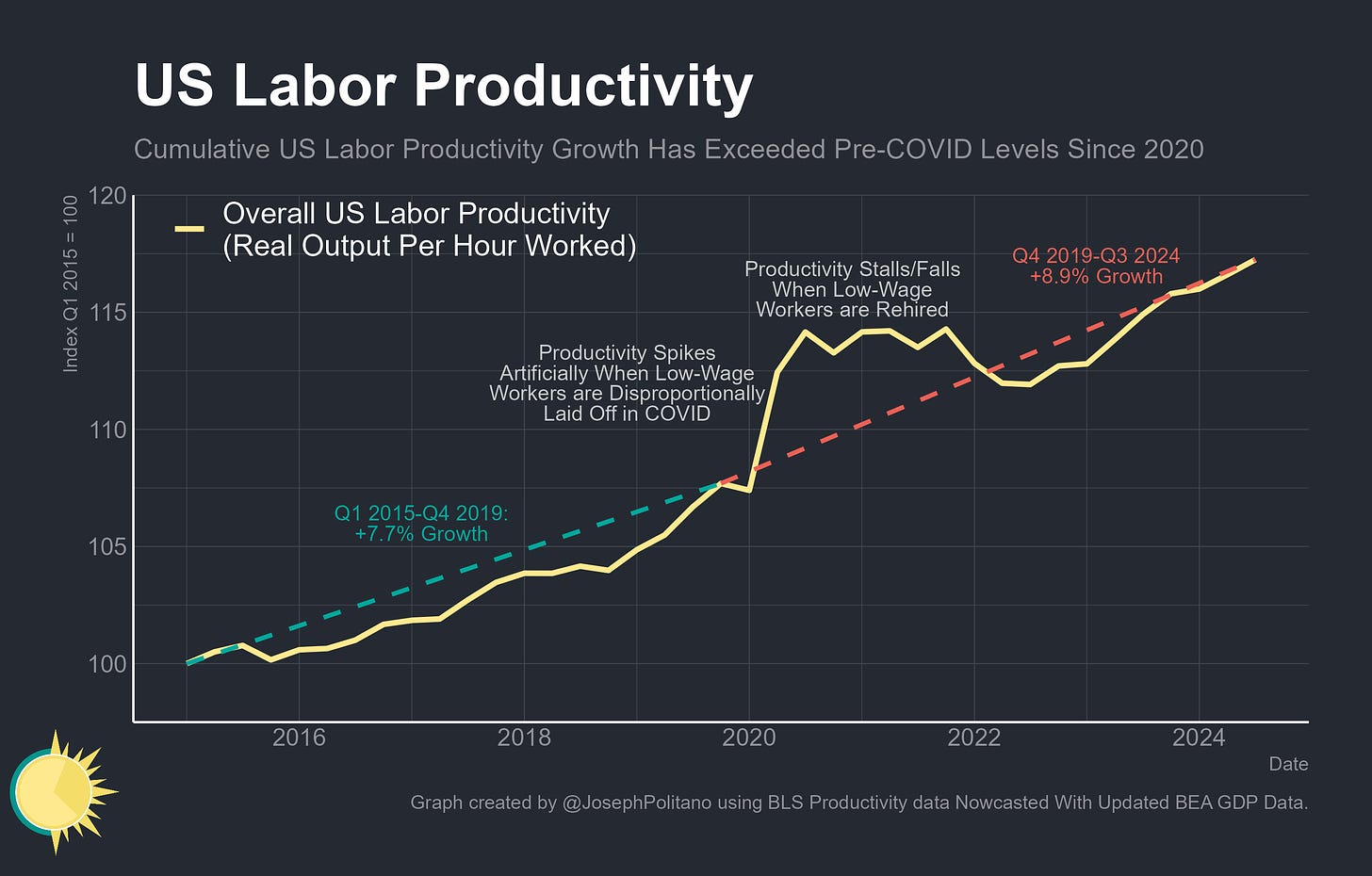

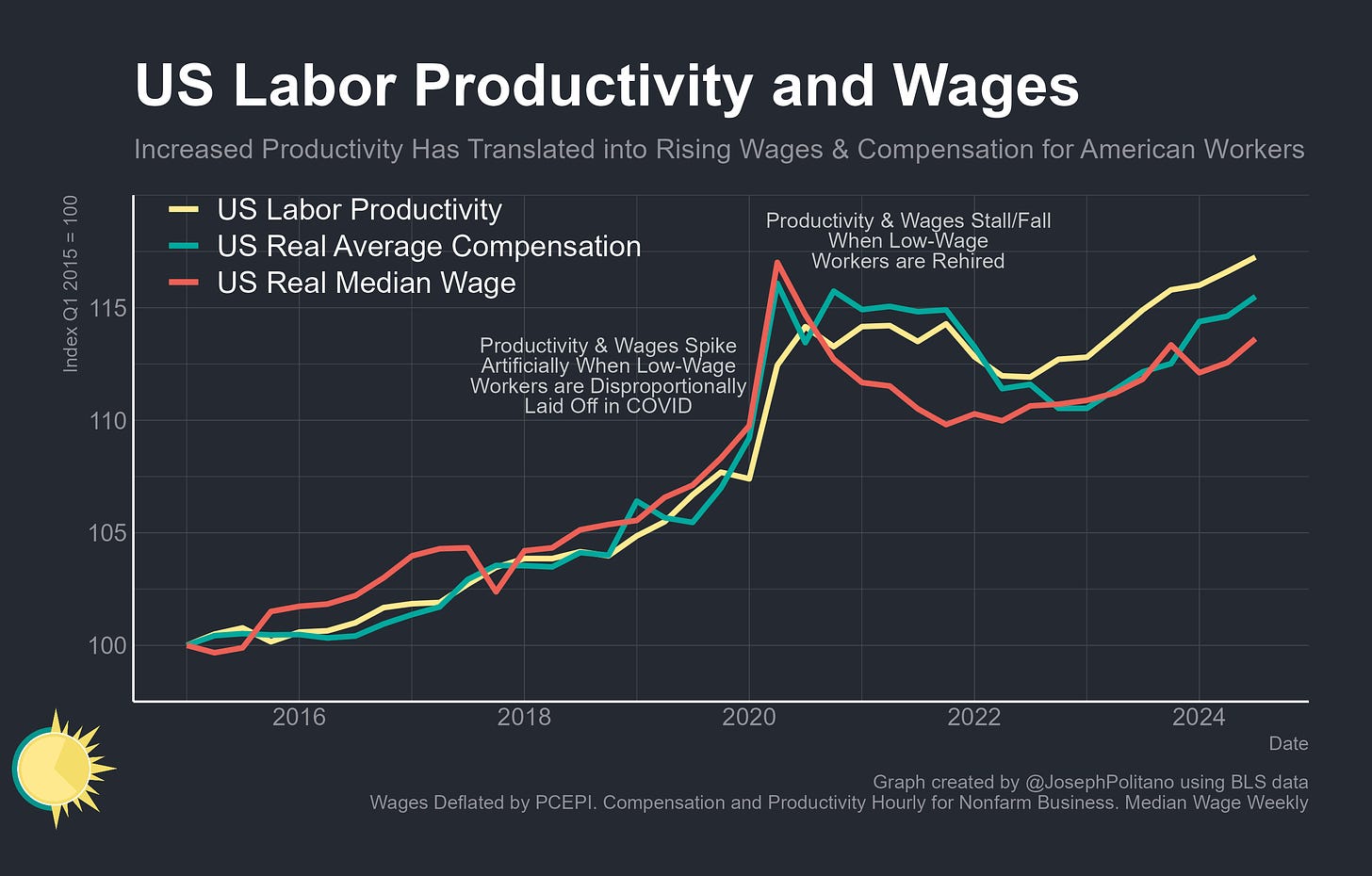

Productivity growth is nothing short of the bedrock of progress—in the long run, creating more with the same amount of labor is the only way to durably increase wages, consumption, and society’s overall prosperity. That makes it such a historic achievement that American economic output per hour worked has risen 8.9% over the last five years—faster than the five years prior or any point in the 2010s—in spite of the COVID-19 pandemic. The already-great productivity recovery we had going into this year got a major upward revision from recent updates to GDP data, and preliminary estimates suggest they’ll get another boost as job growth will likely be revised down significantly at the start of next year.

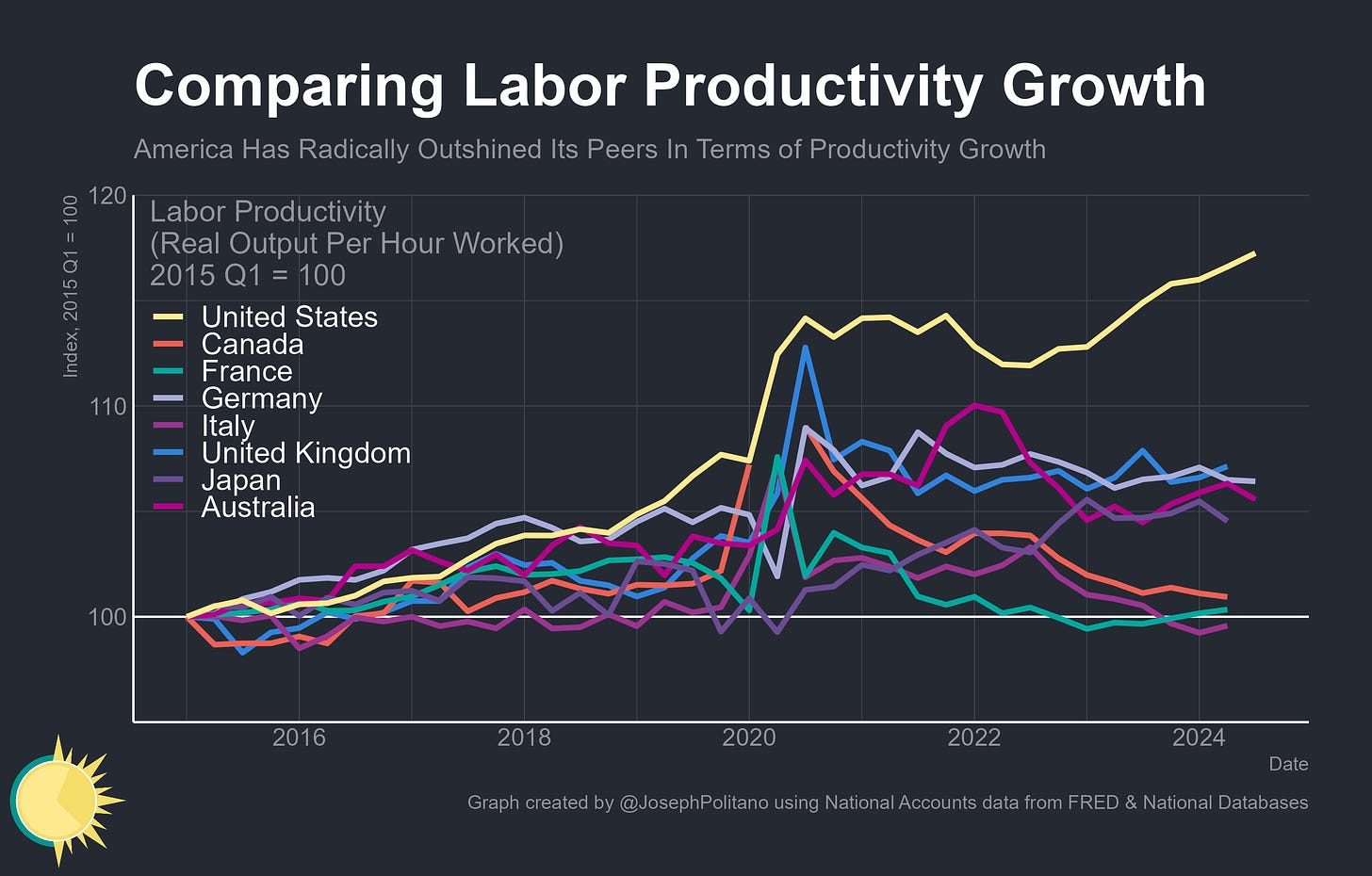

That success is all the more remarkable compared to the dismal productivity numbers seen across many of America’s peer nations and how long it took US productivity growth to sustainably recover from the Great Recession. Since late 2019, the US has seen more than double the productivity growth of the next-fastest major comparable economy, building on an already significant lead it built up in the years before COVID. Plus, unlike the 2nd-place UK, the US has achieved this while increasing overall employment levels instead of leaving less-productive workers out of a job.

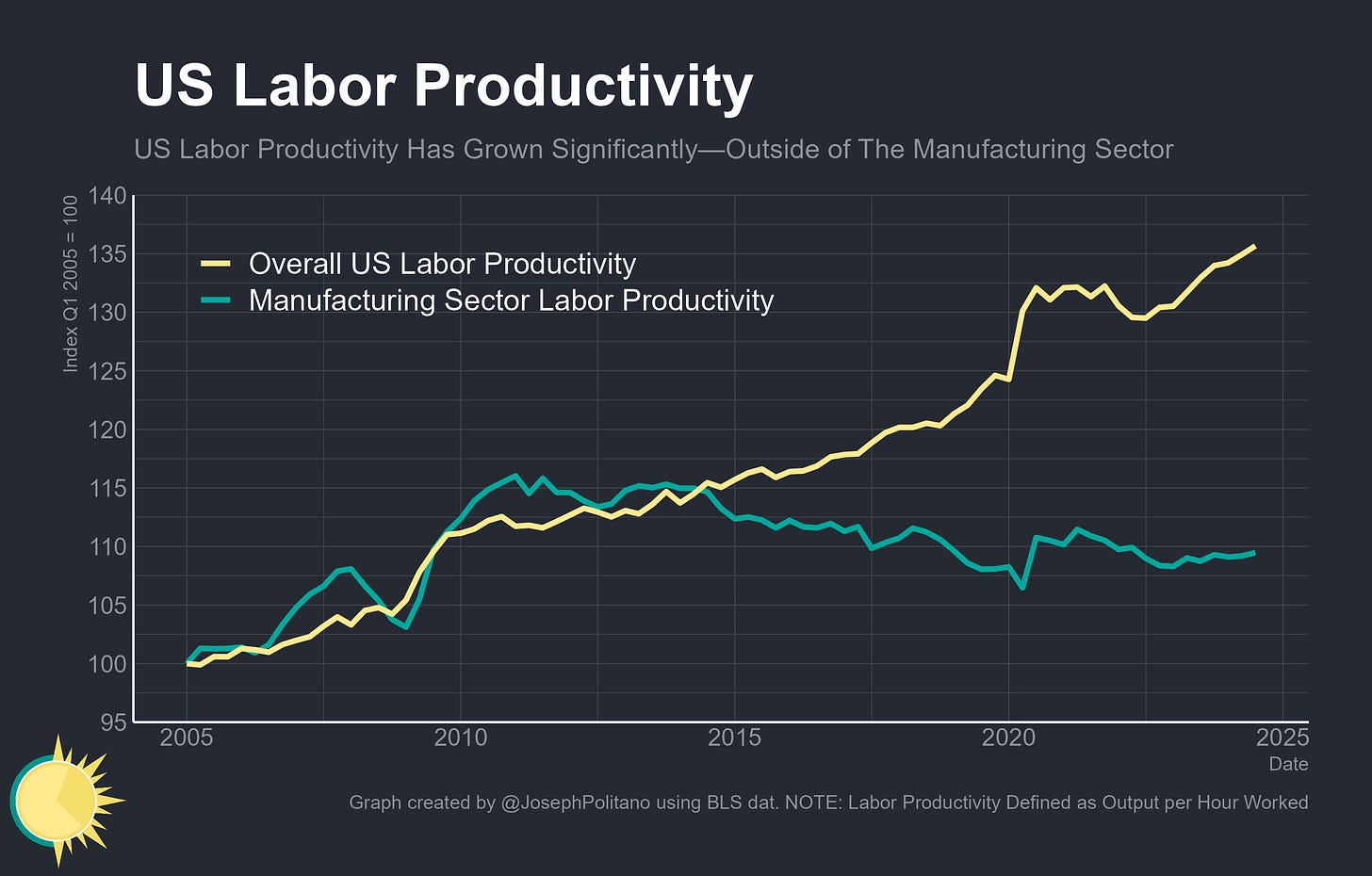

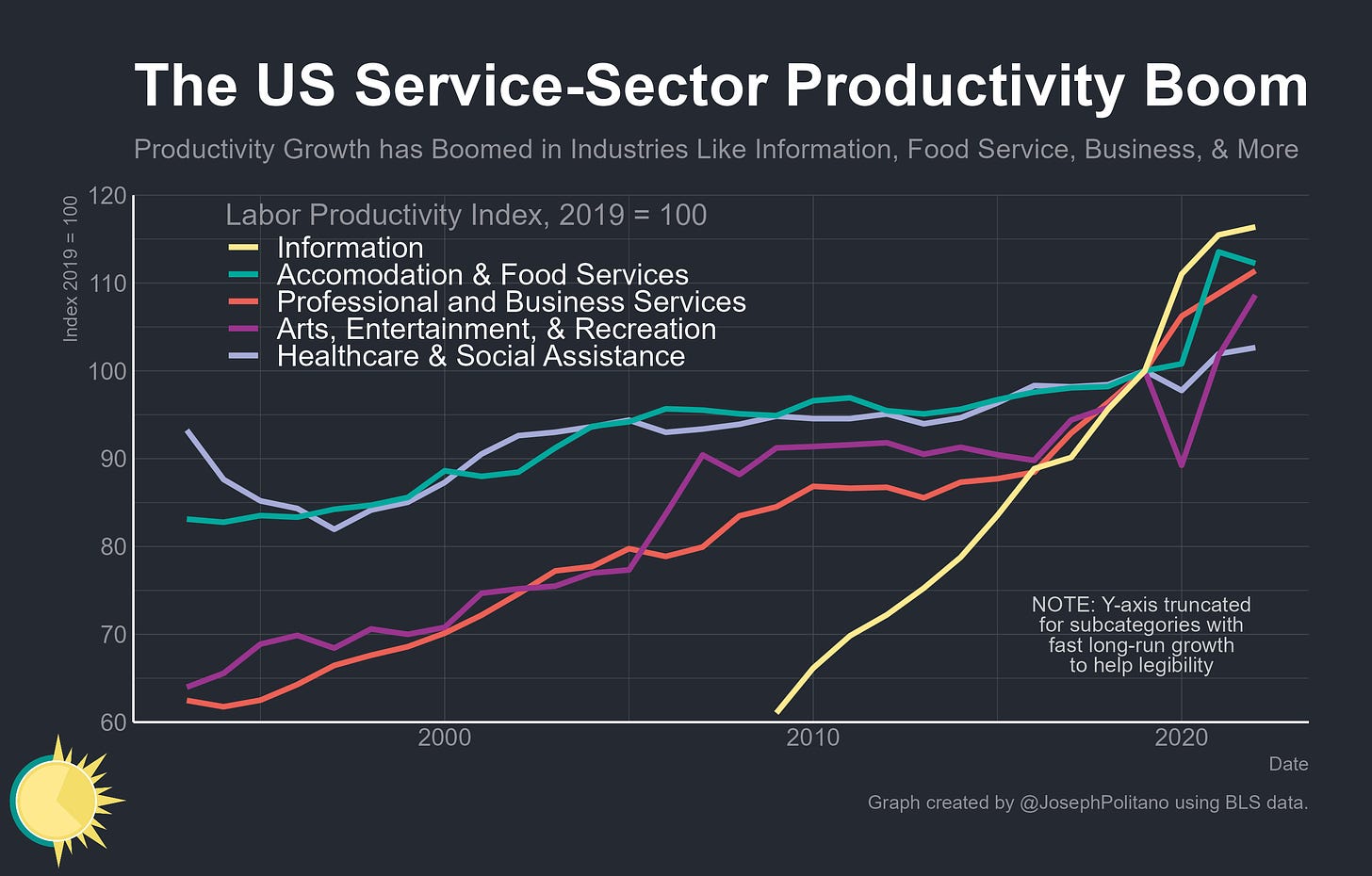

Historically, spurts of productivity growth are most concentrated in the manufacturing sector and manifest only slowly in services—in the classic example, it is hard for barbers to get faster at giving haircuts even as razor manufacturers rapidly get more productive. However, the endemic problems with American industry has meant that manufacturing productivity remains stagnant even amidst heavy government emphasis on industrial policy over the last four years. Thus, the nation’s recent productivity boom comes almost entirely from the service sector—cooks, programmers, drivers, nurses, bankers, teachers, cleaners, managers, caregivers, and more have all gotten significantly more efficient at their jobs over the last four years, with the gains in some subsectors being historically unprecedented in both speed and scale.

It is essential for America’s industrial policy efforts that manufacturing productivity growth return eventually, but it is much, much more beneficial for the country overall to have productivity improve among the service-sector jobs that make up the vast majority of employment, consumption, and economic output. The recent productivity boom has delivered significant gains in Americans’ real wages throughout the pay distribution, which in turn has enabled higher household consumption and increased personal welfare.

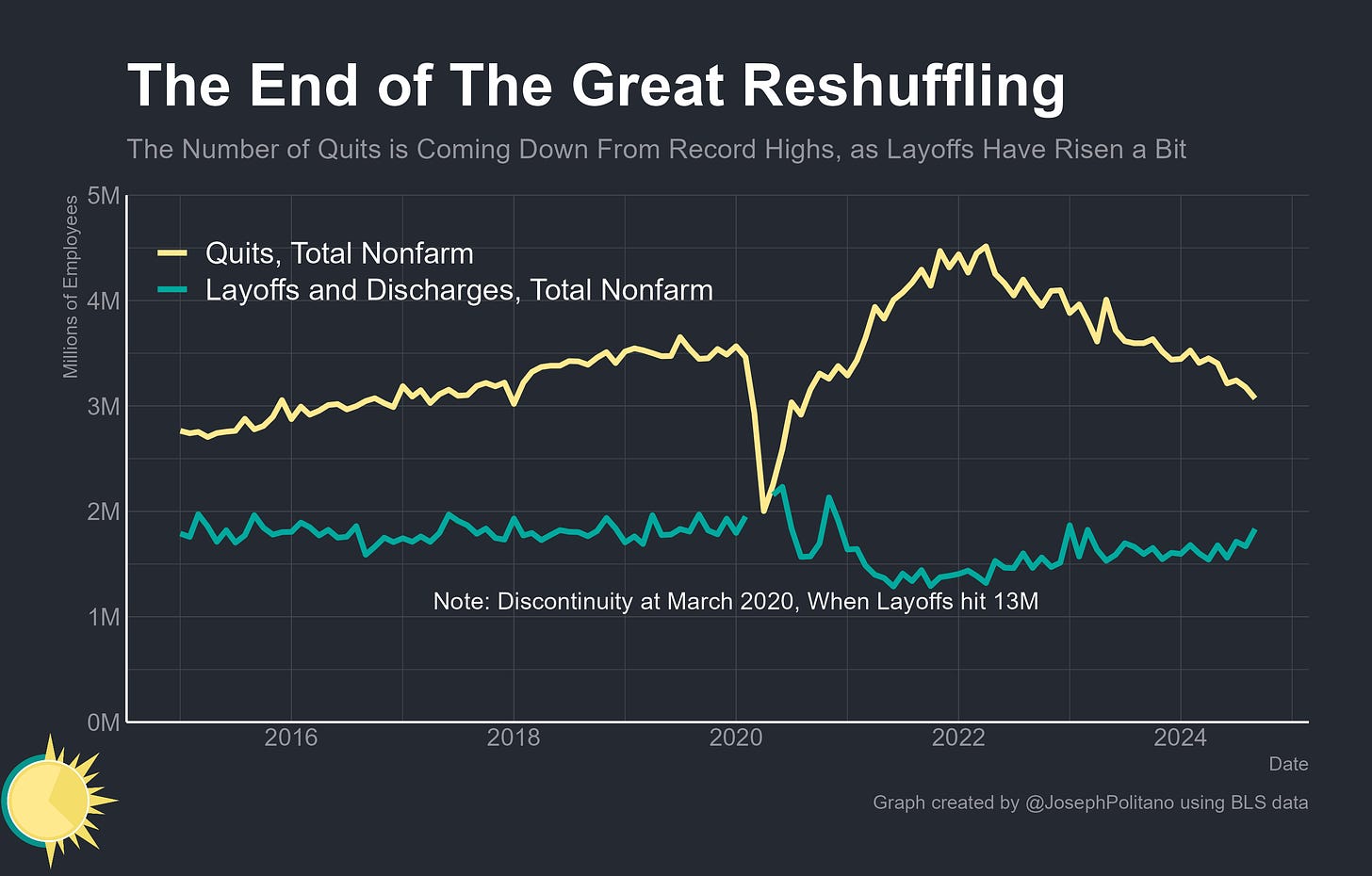

The causes of this boom are multifaceted but primarily stem from the strength of America’s labor market in 2021 and 2022, when businesses invested significantly in productivity-enhancing capital goods, work from home became a permanent facet of white-collar life, and Americans quit low-productivity jobs for high-productivity ones at record rates. That period of intense labor demand planted seeds that have sprouted into even greater efficiency as the labor market has cooled—newly hired employees have adapted to their higher-paying roles, businesses’ capital investments have steadily come online, and the supply chain issues present throughout the early pandemic have eased significantly. In many sectors and industries, the fundamentals of work were completely restructured in a way that forced greater efficiency.

However, as interest rates then rose and the US economy cooled, labor demand has continued to slow to the point that America’s service-sector productivity boom is now at risk. Unemployment is up over the last year, the job churn that drove so much of early-COVID productivity gains has slowed to a crawl, hiring has fallen to recessionary levels in the high-value-added white-collar industries that represent the best of American business, and investment in some of the key fixed assets necessary for greater automation has declined. If the labor market slows further, America’s service sector productivity boom could be undermined at a key moment just as AI tools with key productivity implications are increasingly seeing mass adoption.

The Where of America’s Productivity Boom

Labor productivity is an essential measure of economic health, and at the broadest level, it is also a simple metric—just take a nation’s real economic output and divide it by the total number of hours worked by all its residents. Yet this simplicity can also present flaws for short-term analyses, as labor productivity can spike as the economy contracts if low-wage, low-productivity workers are disproportionately laid off (as was the case in early COVID), and productivity can tank when the opposite happens (as was the case in 2021-2022). Thus, although there was plenty of early evidence for an American productivity boom, it took until recently to confirm its full strength.

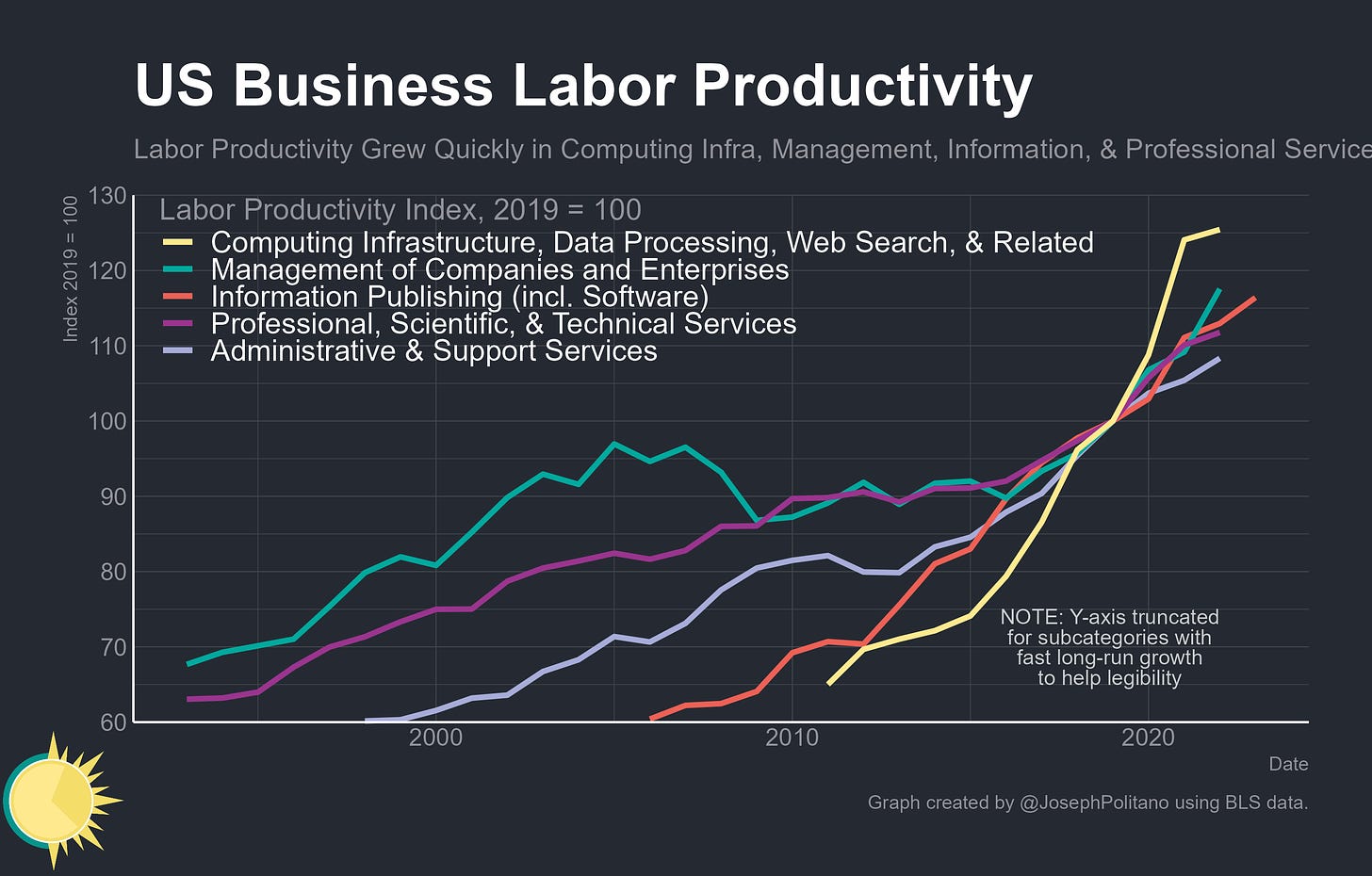

At the sub-industry level, productivity data is sparser and subject to even more fluctuations, so detailed 2022 and 2023 estimates weren’t even available until recently. That newly available data shows a notable acceleration of productivity in key white-collar sectors like professional & business services plus the information sector (which includes many rapidly growing tech companies). Meanwhile, previously stagnant sectors like accommodation & food services saw an unprecedented rush in productivity when they were forced to radically reorganize in the early pandemic, and those efficiency gains have proved durable in the years since. Finally, in other service sectors like healthcare and recreation, productivity growth was volatile but generally followed the post-2008 trend.

Perhaps the most fundamental example of post-COVID productivity growth comes from the professional, business, and information sectors that have been disproportionately large contributors to overall GDP growth post-COVID. These subsectors are the largest areas of the economy that were completely reshaped by remote work—this September, roughly 1/3 of all labor performed in these industries was done at home—and that has significantly contributed to their productivity surge. Productivity growth in computing infrastructure (like Amazon web services), web search (like Google), and management all increased significantly from remote work, with areas like publishing (including software) also seeing a decent growth boost. Professional, technical, and administrative services—lawyers, accountants, scientists, management consultants, clerks, and more—also saw decent productivity gains.

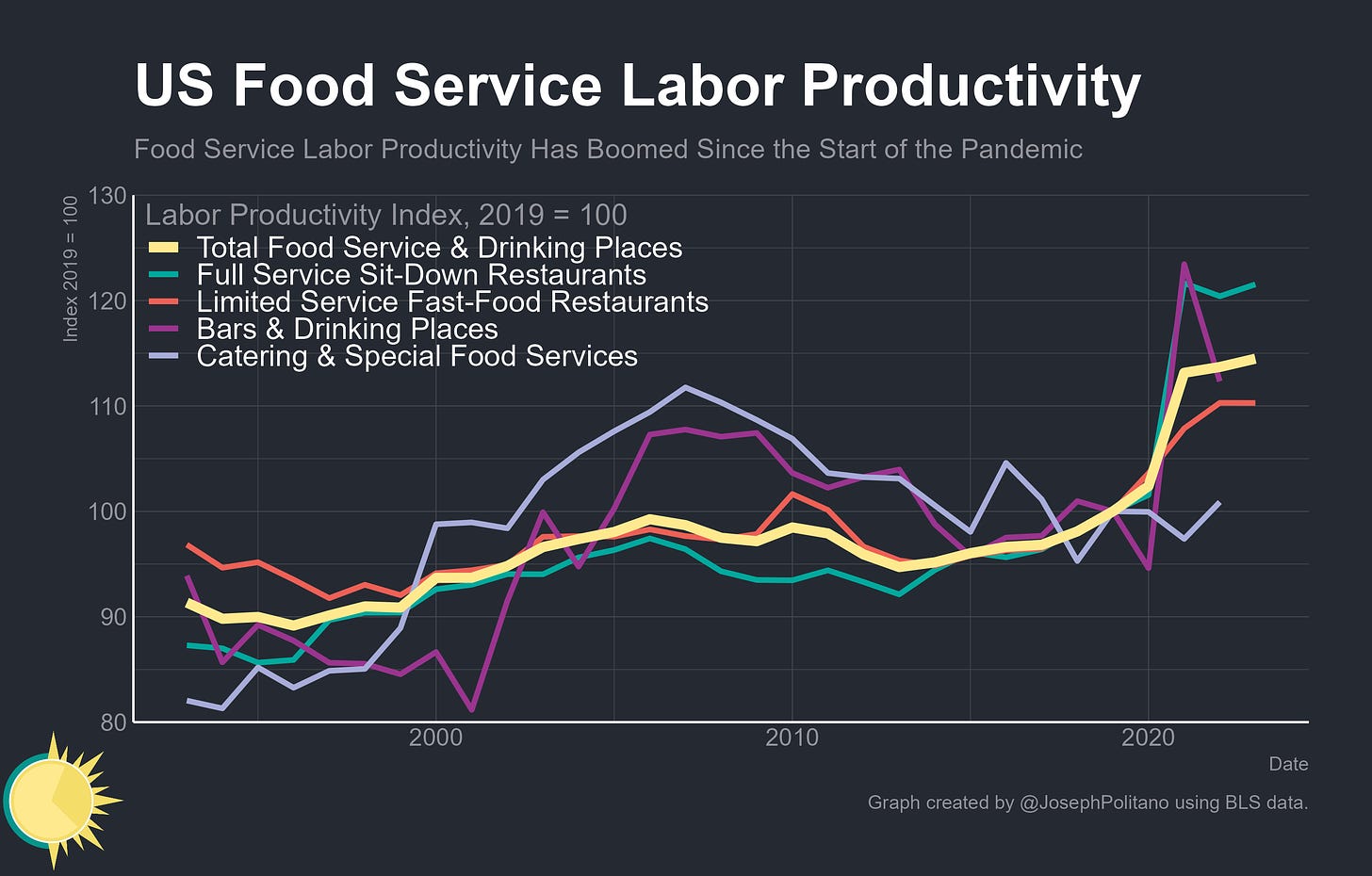

Yet perhaps the more notable productivity boom comes from sectors that were previously stagnant but shocked into efficiency over the last five years. The archetypical example here is food service—it is difficult to make the process of cooking and serving food more efficient, and wage levels for cooks & waiters had long been low enough to preclude the need for greater automation. Thus, productivity gains were minimal even as the sector grew from 6.5M employees in 1990 to 12.1M employees in 2019.

Productivity skyrocketed in 2020—which shouldn’t be too surprising considering employment was down 2.2M and the lowest-paid workers tend to be the most likely to be laid off. Yet what’s remarkable is that even as large numbers of workers were rapidly rehired, productivity only continued to improve. As the labor market tightened restaurant wages skyrocketed, increasing by more than 15% year-on-year at some points, forcing owners to invest in productivity-enhancing technologies behind and in front of the counter while sharing service between mobile ordering, delivery, and sit-down customers. Price-adjusted restaurant spending has increased by 10% since January 2020—Americans are eating out more—while employment has only increased by 1.6%—relatively fewer workers are needed to cook and plate that increased restaurant demand.

The How of America’s Productivity Boom

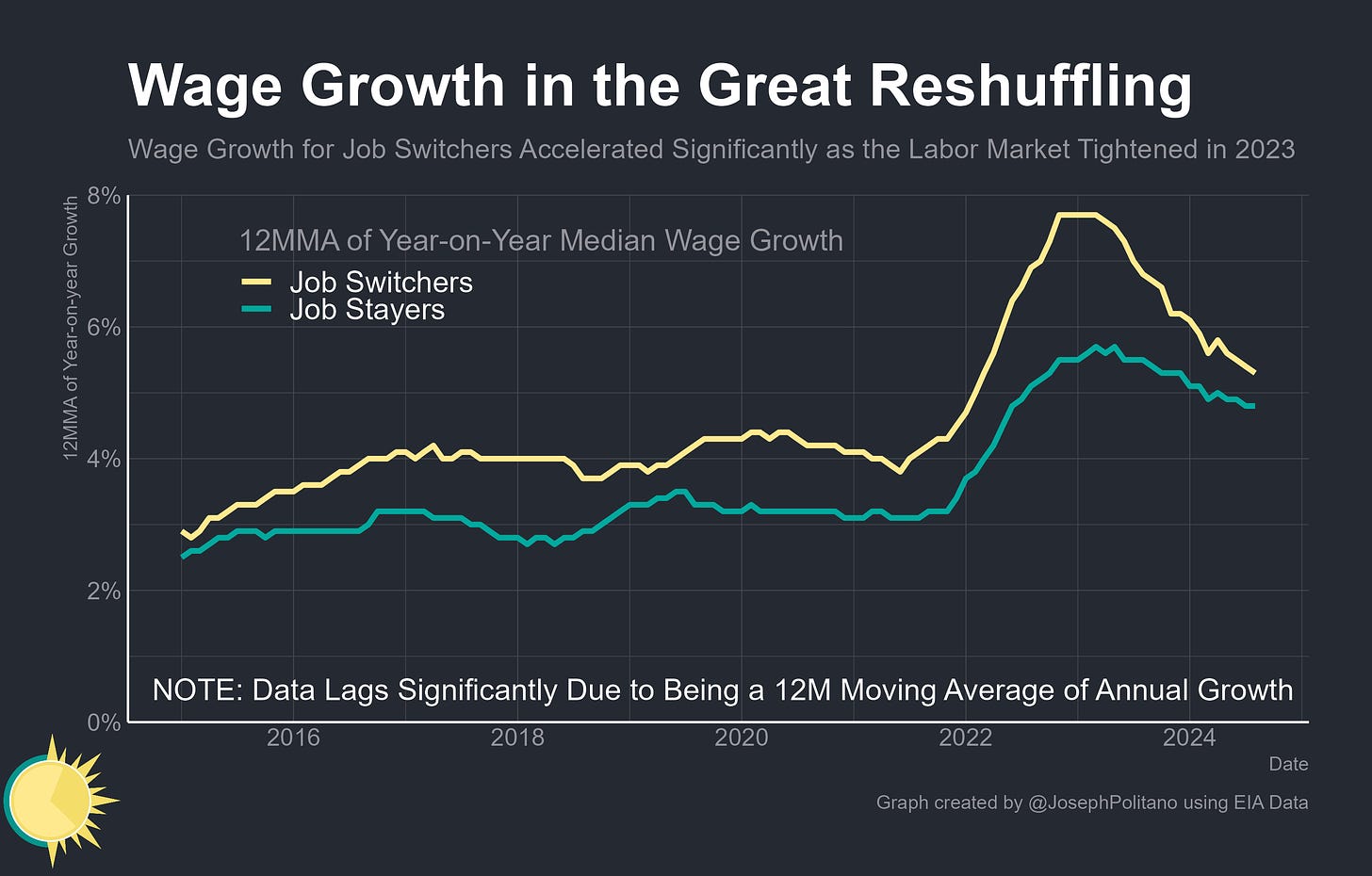

How did much of this service-sector productivity boom happen? The high-pressure labor market of the early post-COVID period delivered many of these productivity gains by reallocating workers to more efficient roles, firms, and industries. In the “great resignation”, monthly job quits, which mostly reflect workers swapping into new higher-paying roles, rose nearly 30% above pre-COVID levels by early 2022. It’s not only that job switching radically accelerated, but the gains to switching also increased as wage growth for job-hoppers reached the highest levels on record. As workers jumped into high-productivity roles this forced low-productivity firms to adapt, raise wages, invest, or die—In the end, research from Arin Dube shows that the lowest-wage firms saw the fastest wage growth while the highest-wage firms saw the fastest employment growth.

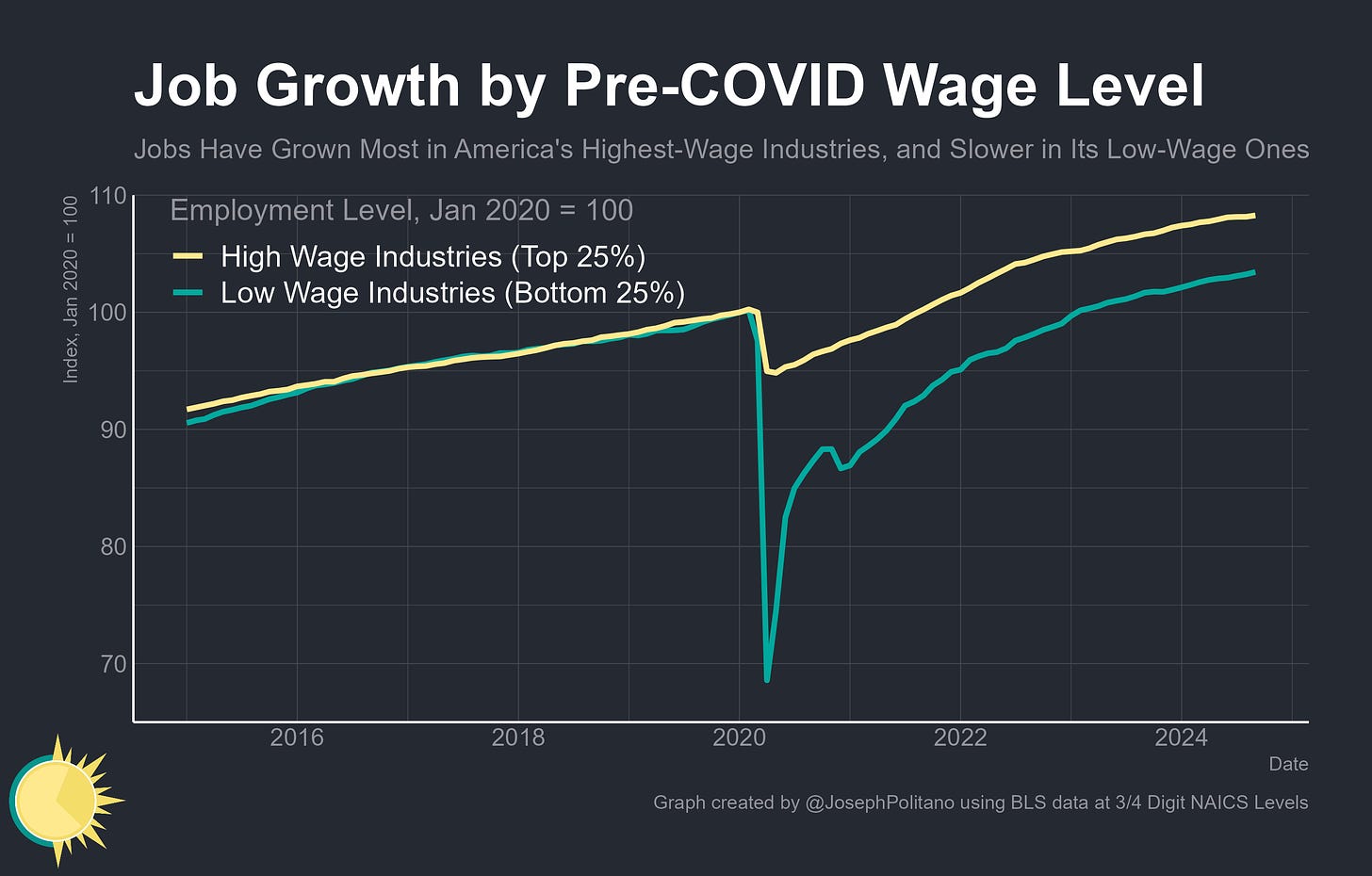

You can see this effect even more clearly by decomposing job growth by pre-COVID industry wage level. Industries that paid the least in 2019—food services, general retailers, hotels, etc—lost the most jobs in early COVID and took years to recover to pre-pandemic levels. Meanwhile, those that paid the most—management, technical services, information, etc—saw much smaller job losses and a much stronger job recovery. The end result was a massive reallocation of workers from less productive sectors to more productive ones—even as employment rates remain at or above pre-COVID levels, the number of new jobs in high-wage industries is up 8.3% vs 3.4% in low-wage industries.

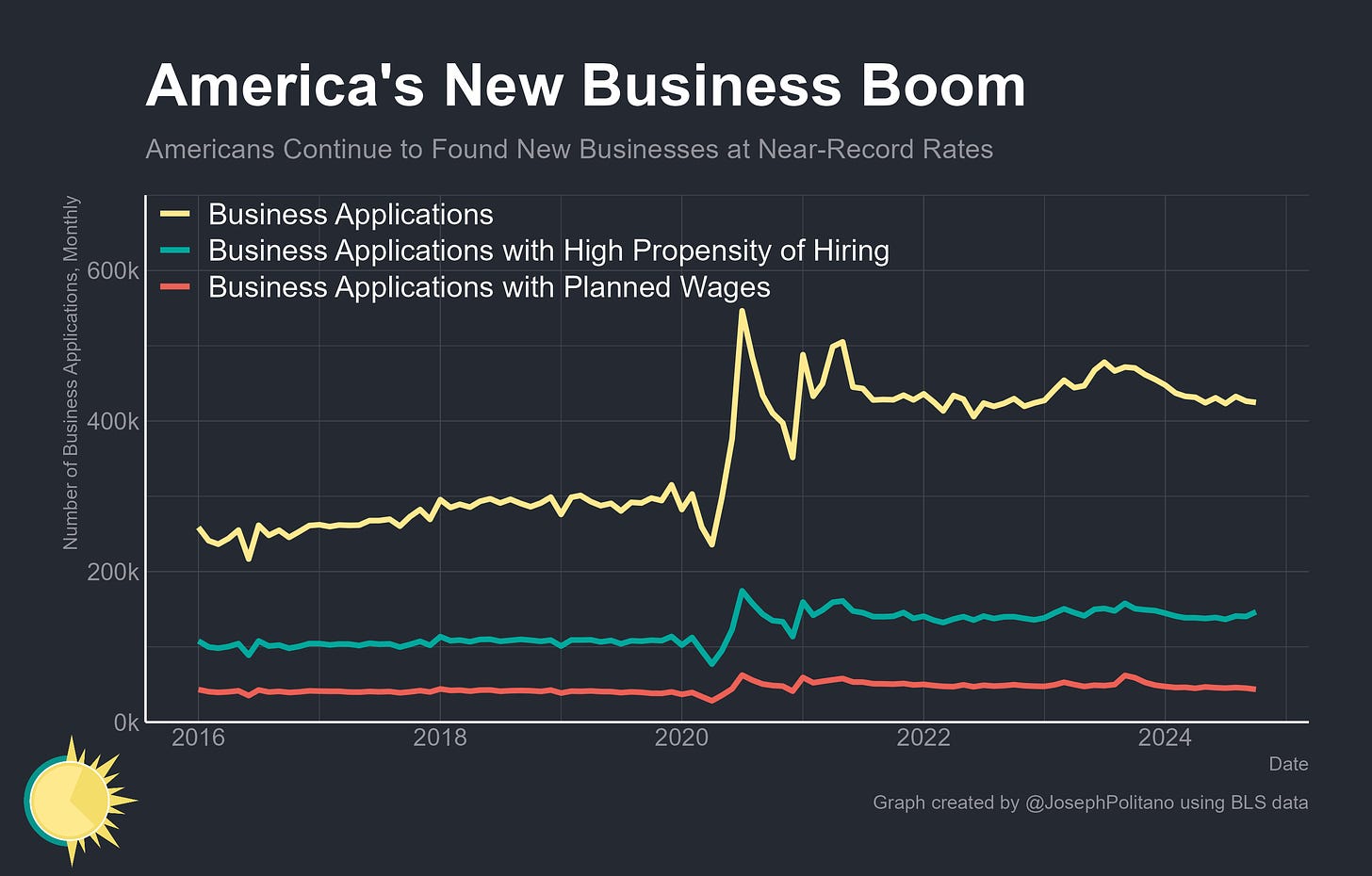

Likewise, the massive increase in job turnover also manifested as a significant increase in entrepreneurship—Americans have been starting new businesses much faster than during the 2010s, contributing to the surge in productivity growth. Post-COVID, job applications spiked dramatically and remained at a permanently higher level, with high-propensity job applications and applications with planned wages also rising significantly. The total number of self-employed workers has risen noticeably since 2019 and they continue to represent a larger share of the post-pandemic workforce. Likewise, business entry by new professionalized startups has rapidly increased post-COVID, with the annual number of newly-formed businesses with employees rising 14.3% from 2019 to 2022 and reaching the highest level since 2006. In total, the business formation boom meant people who could earn more working for themselves took their chances on self-employment, incumbent firms were pressured to innovate by a rush of hungry challengers, and investment accelerated as companies old and new sought to do more with the workers they had.

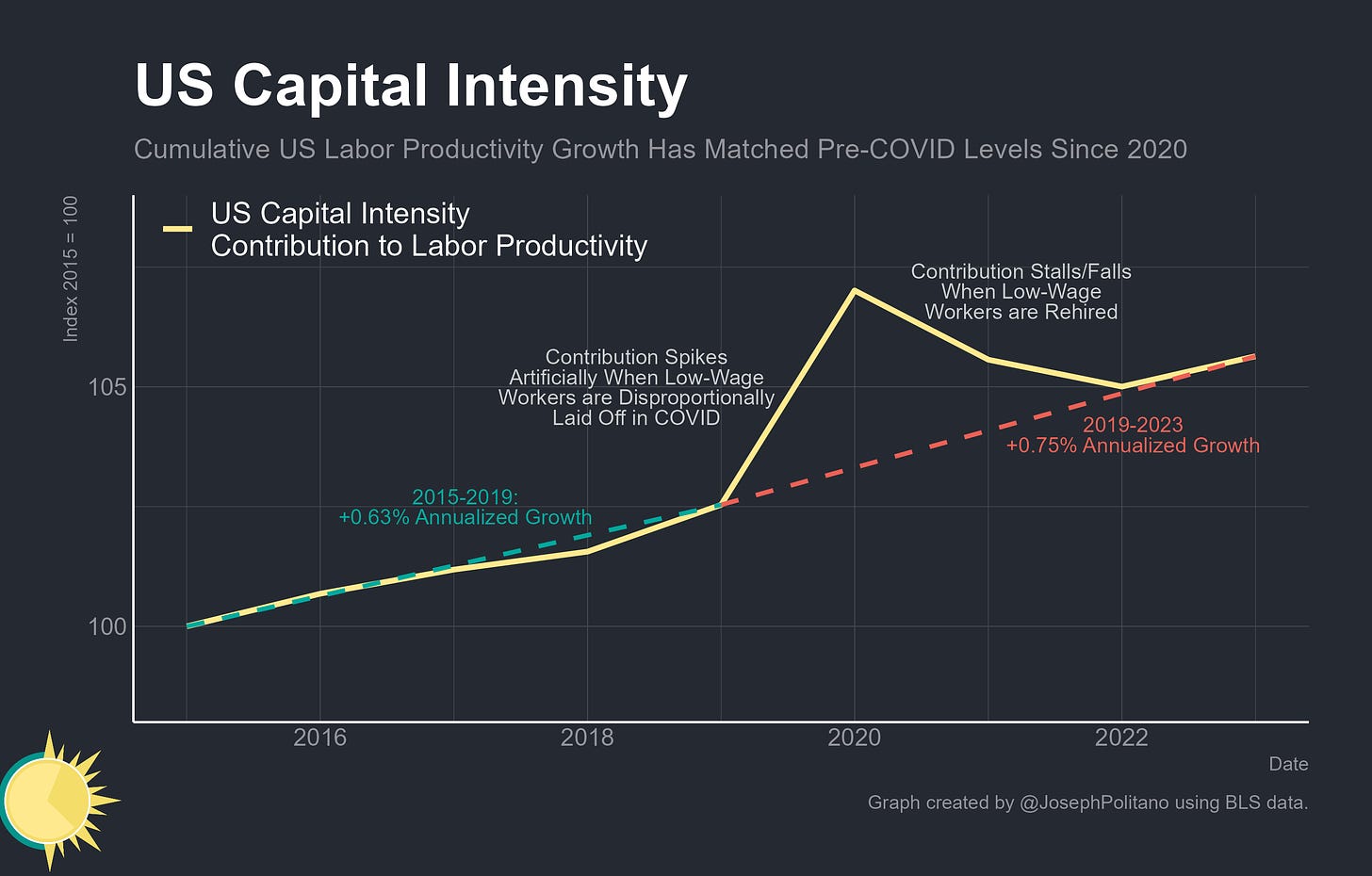

Indeed, America’s capital intensity—the amount of computers, machines, factories, and other assets used per hour worked—has also increased significantly post-COVID, contributing to strong productivity growth. From 2019 to 2023, the contribution of capital intensity to labor productivity growth was even stronger than throughout the four years preceding COVID. In white-collar industries like professional & business services, the recent rush of investment was particularly large and contributed to the sector’s outsized productivity gains.

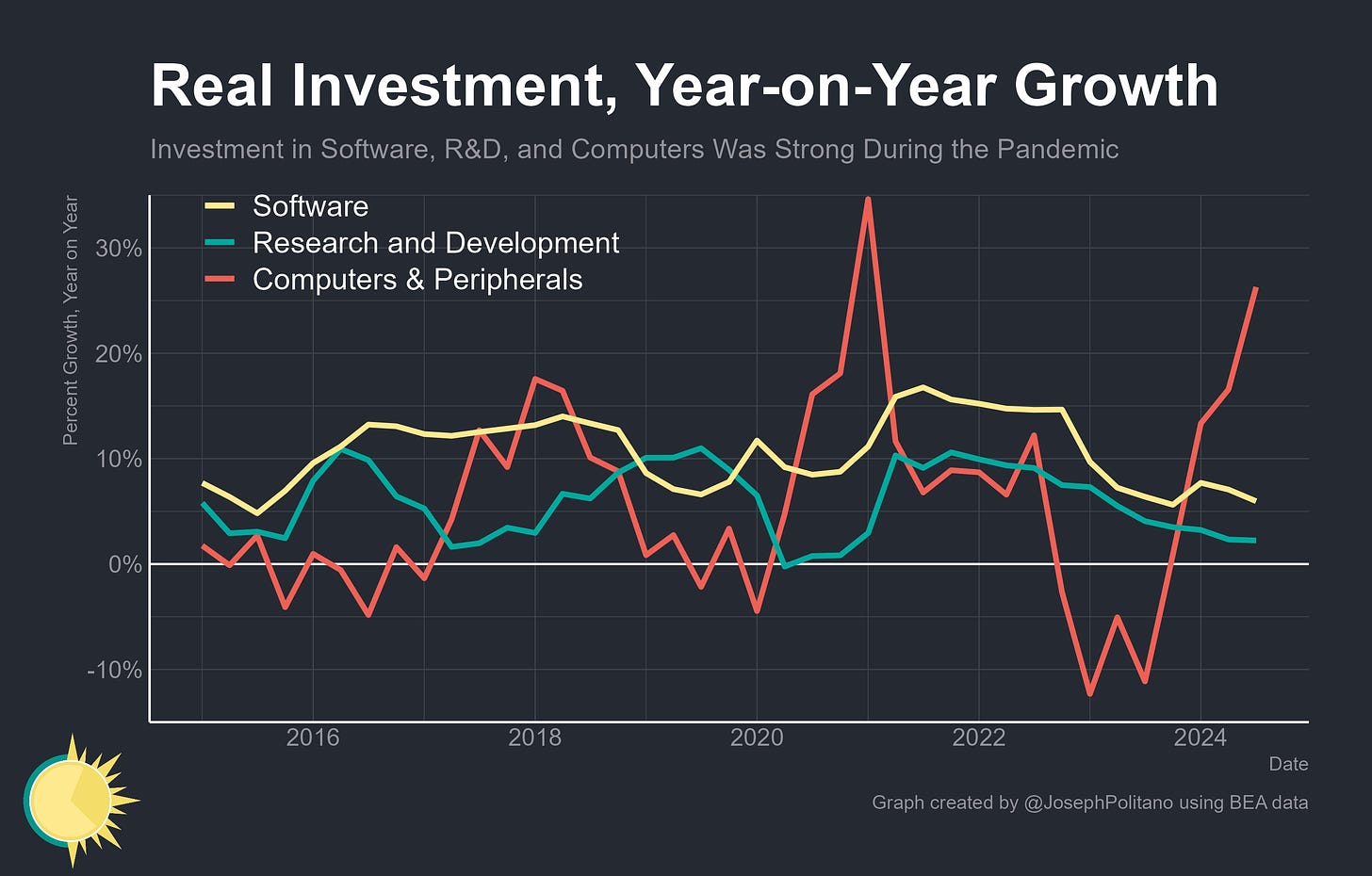

In particular, real investment in key high-tech productivity-enhancing items like computers, software, and R&D all remained strong in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic. Software and computer investment surged with the 2020 work-from-home wave, while R&D output initially slowed but made a swift rebound in 2021. Today, investment in software and R&D may be slowing as the economy copes with the effects of higher interest rates, but investment in computers continues to skyrocket amidst the AI boom.

Conclusions

To abuse an exercise metaphor, the US economy spent much of the immediate aftermath of the pandemic “bulking”—using expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to intentionally run the labor market hot. That helped America recover quickly from the pandemic and steadily build up its underlying “muscle strength”—productivity growth. Part of the consequences of that effort was the creation of “excess fat” as the rapid increase in aggregate demand overshot economic capacity and led to a surge in overall inflation. Then the US spent the last two years in the “cutting” phase—losing the “excess fat” by intentionally suppressing demand and cooling the labor market. That “cutting” has exposed how defined the muscles were under the surface, but if it goes too far the US could start losing muscle mass instead of fat.

It’s also worth noting how little of this productivity boom can be ascribed purely to technological innovation—other high-income countries like the UK, EU, Japan, Australia, etc have the same access to the teleworking tools and artificial intelligence programs that the US has, but none of them have productivity booms on the scale of the US. It’s the combination of technological innovation and macroeconomic incentives for its rapid deployment which, when combined, brought American productivity growth back up.

The US was unique among high-income nations for targeting its early COVID relief towards people moreso than jobs—in March 2020, the federal government did not have the literal capabilities to stand up furlough schemes at the size and scale of countries like the UK, so policymakers had to allow more workers to lose their jobs and focused instead on providing aggressive income support via expanded unemployment and stimulus checks. Many laid-off workers used their time unemployed to find better, more productive jobs. Loose monetary policy ran the economy hot, mixing with America’s flexible labor market institutions to create even more worker turnover and fixed investment in ways most other countries proved unable to replicate.

These developments boosted productivity, but partially with a long lag, and thus we may see near-term productivity decelerations due to the lagged effects of those developments’ recent reversal. Yet the immediate forecast for productivity growth still remains a significant improvement over the dismal growth of the early 2010s—highlighting the structural benefits of higher employment and tighter labor markets. And if the macroeconomic environment returns to full strength, the US may be able to sustain an even longer streak of historic productivity growth.

Interesting. I’m not convinced, though, that trend labor productivity growth really has increased. Rather the elevated productivity growth rates seen over the past year or so likely reflected more a catch up dynamic. And more recently labor productivity still undershoots the level of its trend (based on an average of statistical trend estimates) but this catch up is close to getting completed. The tailwinds of high labor productivity growth might well fade in 2025.

https://open.substack.com/pub/janjjgroen/p/q3-2024-productivity-and-wages-still

Not convinced. Raising prices and increasing the velocity of money, which is easy to do in the service economy, coupled with increased online purchasing and online advertising, can greatly increase the GDP without increasing hours worked. A strong dollar also helps. Doctors giving patients 10 minutes, instead of 1/2 hour, and charging more than 1/.3 the previous rate, greatly increases productivity but not recommended.