America's Weakening Labor Market

Job and Wage Growth Have Decelerated Substantially This Year—Signaling a Likely End to Exceptionally Strong Pandemic-Era Labor Markets

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 34,000 people who read Apricitas weekly

The US labor market has cooled significantly over the last two years—ending a recent period of exceptional strength and returning to a situation roughly similar to pre-COVID. Talks of labor shortages continue to wane, with the share of small businesses having trouble filling positions falling to the lowest level since early 2021 and hovering at rates equivalent to late 2019. Gross hiring dipped below 6M in July as slowing demand reduces firms’ incentives to hire new workers and makes it harder for those employed to switch to better jobs. Over the last three months, net growth in nonfarm payrolls has fallen to just above 100,000 per month—sufficient to match population growth but not much else.

Wage growth is likewise decelerating—robust data from the Employment Cost Index (ECI) shows private-sector wage growth at 4.6% through the end of June while the higher-frequency measure of average hourly earnings has dipped below 4.3% as of August. Meanwhile, leading indicators like growth in posted wages on Indeed have fallen even more relative to their 2022 highs.

The net effect of slower job and wage growth is that private sector Gross Labor Income—the aggregate sum of wages and salaries in the economy, an important cyclical indicator—has decelerated nearly back to normal 5% growth rates over the last year. The Bureau of Economic Analysis’ measure, which incorporates bonus and stock option data, actually shows marginally below-normal growth, meanwhile, high-frequency measures derived from nonfarm payroll data are extending the trend of deceleration observed in the more robust measures derived from ECI and employment data.

Importantly, that high-frequency nonfarm payroll (CES) growth will most likely be revised downward for 2023—lagging but comprehensive QCEW data derived from mandatory UI filings and tax forms imply that job growth was smaller than original CES estimates. Preliminary official benchmark revisions suggest nonfarm payrolls were 306k smaller in March 2023 than previously reported, a drop of roughly 0.2%. The downward revisions are also heavily concentrated in some of the industries hit hardest by the slowdown of the last two years, particularly transportation & warehousing and professional & business services. In other words, the weakening of the labor market has likely already been somewhat more profound than high-frequency data suggests, and growth may have already converged to pre-pandemic levels.

Gross labor income growth has had a strong relationship with consumer spending throughout the pandemic and is a major driver of inflation in housing and other core services; its deceleration is bringing nominal spending and inflation down with it. That’s been good news for the Federal Reserve, which has been aiming to get inflation down for years, and has thus far managed to do so without forcing unemployment significantly higher. However, further slowdowns in the labor market could quickly present a major drag on American economic growth, and businesses are highly pessimistic about the pace of hiring for the upcoming year.

The End of The Great Reshuffling

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the early-pandemic labor market was the rise in quits that got dubbed the “Great Resignation,” but which was more accurately a “Great Reshuffling.” Workers were quitting jobs at record rates, but the vast majority of these quits reflected job-to-job transfers—elevated labor demand forced businesses to offer higher wages to poach jobseekers from other firms and allowed workers to move into higher-productivity occupations/industries more easily. That “Great Reshuffling” is essentially over—the number of workers quitting jobs each month has now fallen roughly 20% from 2022 highs. In low-wage sectors the drop in the quits rate has been particularly acute—falling from a peak of 6.1% to 3.9% today in accommodation and food services and falling from 4.9% to 3.4% in retail trade—and wage growth in those sectors has likewise decelerated substantially.

The end of the “Great Reshuffling” has also brought about a major change in the shape of job growth—in particular, professional and business services, finance, information, and other high-paying white-collar services that boomed in the early pandemic have slowed their hiring significantly. Meanwhile, industries like government and health services, which were depressed in the initial COVID recovery, have seen a much stronger rebound as of late. That’s not to discount government or healthcare jobs—they still represent significant boosts to aggregate household income, and it’s natural for these sectors to regain jobs now given how far below pre-pandemic employment levels they were when entering this year. Yet the particular weakness in high-income industries has important downstream effects that likewise shouldn’t be discounted.

Still, the broader pace of job growth has slowed down enough to begin showing up in unemployment numbers even as overall joblessness remains relatively low. Long-term unemployment, as a share of the labor force, has picked up from 1.1% in April to 1.4% today—a higher number than at any point in 2019.

Perhaps most worrying, companies’ hiring expectations have deteriorated significantly since 2022 and are now at some of the lowest levels since the Atlanta Fed began asking about them 5 years ago. On net, firms expect to increase payrolls by less than half a percent over the next year, and their pessimism comes with more certainty than at any point since the beginning of the pandemic. Falling revenue forecasts are partly driving the slowdown in expected hiring, with sales growth expectations sinking to the lowest level since late 2020.

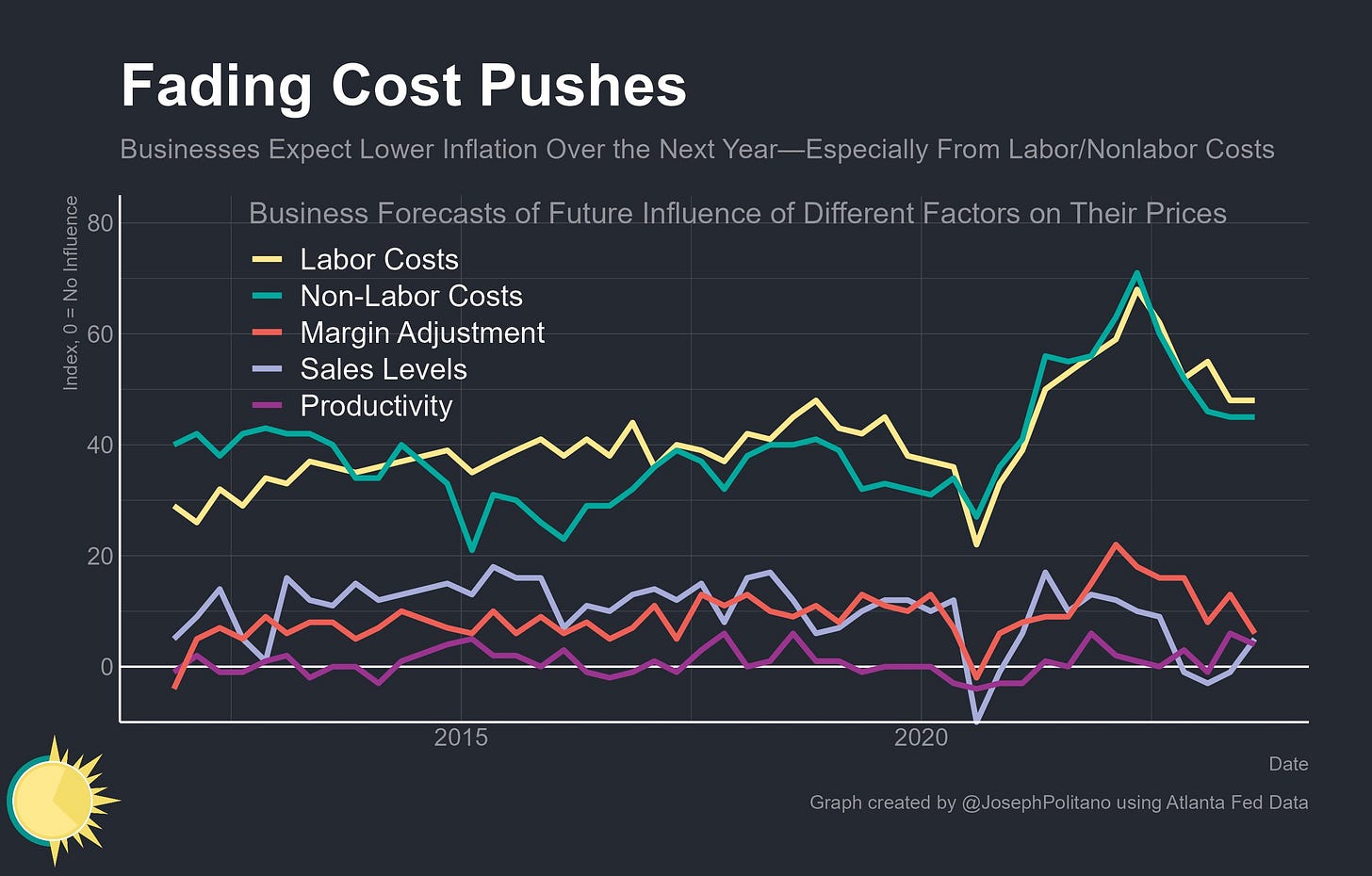

The flip side is the same forces driving lower revenue and hiring expectations are also cooling firms’ inflation expectations—which have fallen to the lowest levels since early 2021. When asked about the future drivers of inflation, companies now expect less upward pressure from labor costs than at any point since early 2021, and overall labor cost pressures remain roughly in line with 2018 highs.

Yet even as the labor market weakens and job growth cools, unemployment remains low by longer-term standards, and prime-age employment rates remain at 20-year highs. Debates on whether or not the Fed could achieve a “soft landing” rested in large part on whether inflation could be tamed without causing a recessionary increase in unemployment. The fact that low unemployment has combined with rapid declines in nominal incomes, spending, and inflation in the absence of a recession is another win for “speed limit” theories that emphasize growth in the labor market over the level of joblessness as drivers of inflation. But by that same token, further slowdowns in job growth could portend economic weakness even if unemployment doesn’t rise.

Hi, great article: A really helpful breakdown of new labor market data. Have you ever looked into whether the Indeed wage tracker leads the ECI? Looks like it might from the chart, and I can imagine a conceptual basis for thinking posted wages on new jobs lead actual wage gains.

Brilliant as always Joseph!