Are Rising Corporate Profit Margins Causing Inflation?

A Response to People Calling for Antitrust Actions and Price Controls to Combat Inflation

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Before starting, I wanted to thank Timothy Lee and Alan Cole from Full Stack Economics for featuring Apricitas as one of their “Six Economics-Related Newsletters You Should Read in 2022.” Thank you as well to all the new subscribers! If you haven’t already, you should follow me on Twitter and LinkedIn so you can catch all the content that doesn’t make it into the blog!

America has experienced an explosion of inflation over the last year. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) has increased nearly 7% over the last year, with gasoline prices up nearly 60% and used car prices up 30%. At the same time, corporate America appears to be doing as well as ever. The S&P 500 is hitting record highs and many companies are posting eye watering profits.

The coinciding rise in inflation and corporate profits has caused some to blame corporate actions for the recent rise in prices. Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren blamed oil companies and grocery store chains for taking advantage of the pandemic to boost prices in order to juice their profit margins. Matt Stoller at the American Economic Liberties Project posited using some back-of-envelope math that 60% of the rise in inflation is driven by corporate profits. The White House pinned the blame for rising meat prices on the meat processing oligopoly.

With this situation, some have pushed for unconventional action to reign in corporations and combat rising prices. The White House is tapping trustbusters throughout the federal government to find ways to use antitrust policy in order to lower prices. Stoller and others have proposed excess profits taxes in addition to robust antitrust measures. Economist Isabella Weber called for a "systematic assessment" of the usefulness of strategic price controls1.

But are corporate profits even really to blame for the rise in inflation? In short, no. High profit margins do not cause, and are often not correlated with, high inflation—and the jump in profit margins is not particularly large. Would antitrust actions help reduce inflation? In the short run it is possible, but not by any significant amount. The items experiencing idiosyncratic price increases due to the pandemic are mostly not in monopolistic or oligopolistic markets. And would price controls be an useful tool in combatting inflation? Not at all.

Prices and Profits

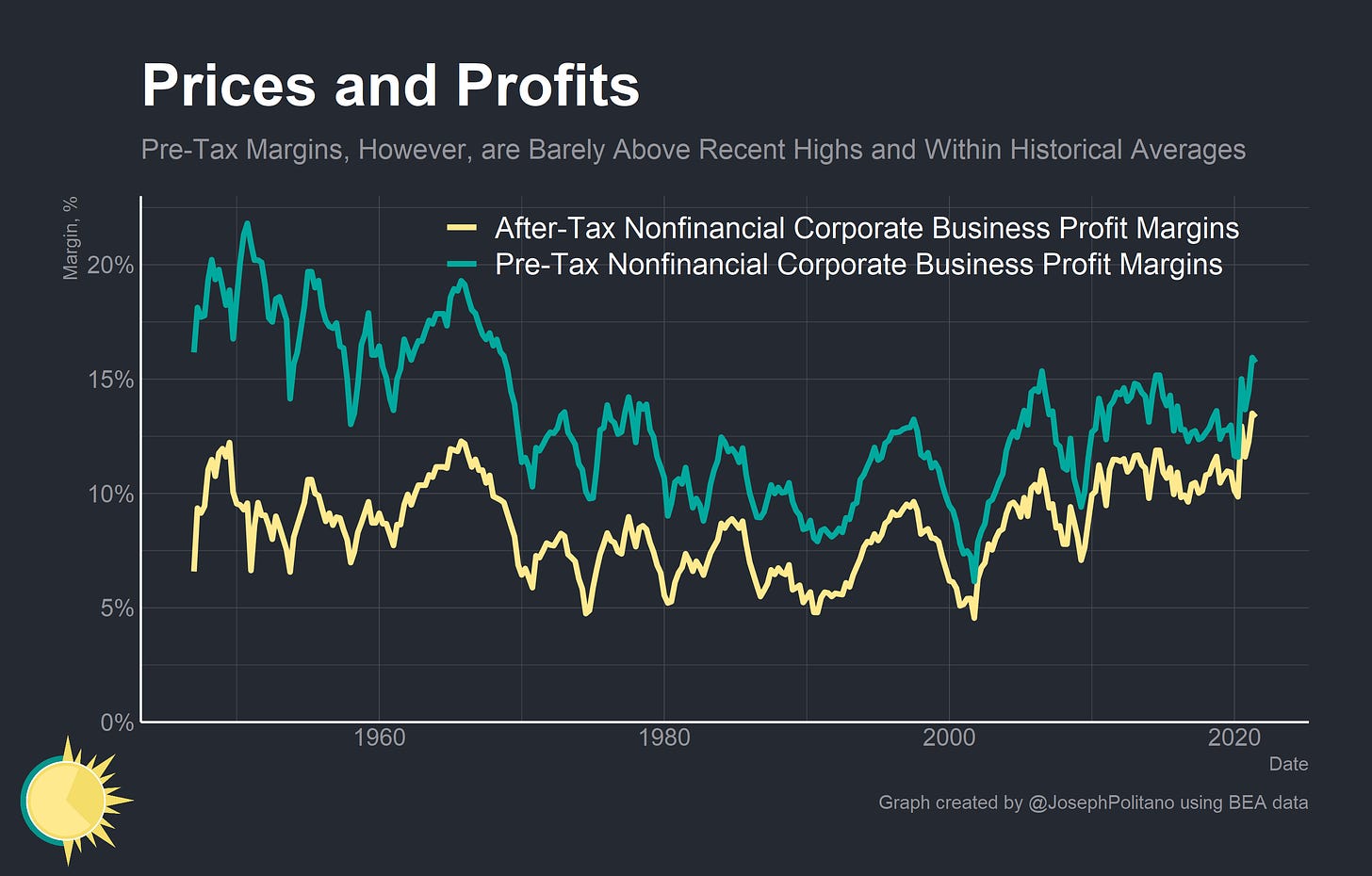

Let’s start with corporate profits. Since 2020, profit margins for domestic nonfinancial corporations have appeared to hit all-time record highs. But it is worth noting that margins, by themselves, have very little correlation with inflation. American corporate profit margins have been near all-time highs for the bulk of the last decade—a decade that saw inflation well below the Federal Reserve’s 2% inflation target. Profit margins can be rising in a low-demand environment and funnel money away from workers and towards higher-income individuals with lower marginal propensities to consume, thereby lowering inflation. This is not happening now, but reveals the flaws in reasoning from a change in profit margins. Anybody who predicted that 2010’s high profit margins portended rising inflation would have been seriously wrong.

Plenty of sources have also been conveniently using after-tax profit margins instead of pre-tax margins. The last few decades have seen a steady decrease in effective corporate tax rates, making the jump in after-tax margins unnaturally inflated by historical standards. Pre-tax margins are well within historical levels, though high by modern standards.

Before we move on here, it is worth acknowledging that aggregate profit margins are plagued by methodological and theoretical issues. For one, Bureau of Economic Analysis is forced to adjust for capital consumption (depreciation) and inventory valuation. Inventory valuation adjustments are of particular interest: the BEA attempts to adjust for a company producing a good at one cost and sale price, keeping the item as inventory for a period of time, and then selling the item at a new cost and sale price. The adjustment brings the unit profit of previously manufactured goods to match the unit profits of goods manufactured at the new cost and sale prices. This adjustment has likely gotten significantly more difficult with rising production costs, shrinking inventories, and increasing prices for final sales. Then the BEA essentially lumps all corporations together to craft total profit margins, so variation between and within industries is completely lost.

The data itself is also subject to revision, so current estimates may be changed as better data sources are incorporated into the BEA’s sample. The National Income and Product Accounts Handbook explains it best:

However, financial-accounting information is more timely than the tax-return data, so it is used by BEA to derive the estimates for the most recent year and for the current quarters. Neither set of accounting data is entirely suitable for implementing the NIPA concept of profits from current production. Consequently, BEA’s procedure for estimating NIPA corporate profits mainly consists of adjusting, incorporating, and supplementing these data.

I would not be surprised if corporate profit margins are adjusted downward when more tax-return data is incorporated, even if they still remain high. Nevertheless, Matt Stoller would point out that total corporate profits are up nearly 40% since the start of the pandemic, meaning that aggregate corporate profits could be pushing up inflation even if profit margins aren't un dramatically.

First, it is worth acknowledging that corporate profits are extremely sensitive and can fluctuate dramatically from year to year. Pre-tax profits jumped 30% from 2011 to 2012 during a period without abnormal inflation. Additionally, the jump in profits is a direct consequence of the jump in federal spending caused by pandemic stimulus measures. When the federal government spends deficit-financed money it definitionally increases the surpluses of the private sector. In other words, when the government borrows and spends money that money has to go to private sector actors (businesses and households) who see a corresponding bump in income. The rise in corporate profits is largely attributable to this increase in spending: money first went from the government to households in aggregate, and now those households are spending money and sending it to corporations in aggregate. The jump in aggregate corporate profits is no more responsible for the rise in inflation than the prior jump in household income.

Crucially, it is worth remembering that these are all profits and margins statistics for domestic corporations. Americans buy significant amounts of their goods abroad, and prices for goods have been rising since the start of the pandemic as consumers were prevented from spending money on services. Looking only at domestic profit margins is missing part of the picture.

Finally, I want to dissect Stoller’s methodology in claiming that profits drive 60% of inflation increases. By his own admission it is only a back-of-the-envelope calculation, but I still think it is a calculation that should not have been attempted given his methodological errors. Stoller takes the total corporate profit per person ($3,081 pre-pandemic, $5,207 today for an increase of $2,126) and then compares it against a 6.8% increase in nominal GDP per capita ($4,752) designed to represent the effect of the increase in the CPI. After removing “normal” inflation (for which he uses 2019’s 1.8% inflation rate) Stoller claims that profit growth is responsible for 60% of inflation.

First, let me just stress that you cannot just compare growth in a quarterly measurement of profits (a flow variable) with growth in a price index (a stock variable). The whole exercise should be moot because of that point, but there are more methodological issues I want to discuss. You also can’t compare GDP per capita (which covers total output in the economy) to the Consumer Price Index (which only covers the discretionary spending subset of the economy). The GDP Implicit Price Deflator, which would have been the proper price index to use, is only running at 4.57%. It is also just number padding to take “normal” inflation as 1.8% instead of the Federal Reserve’s 2% target, and Stoller makes no effort to account for imports, exports, or differences between industries. Finally, there is no causal analysis here. One could just as easily repeat this exercise by ascribing all inflation to the increase in income caused by the stimulus checks, because without good causal inference the whole thing is just conjecture about what “actually” caused inflation.

Antitrust and Inflation

Even if the rise in corporate profit margins are not causing inflation, is it possible that antitrust actions could alleviate price increases? Somewhat, but the applications are much more limited than necessary to bring inflation back to normal levels. Take meatpacking, which the Biden administration is taking aim at. It is likely true that meatpackers form a sort of oligopoly and that they have increased prices more than would be possible in a competitive market. Meatpackers are being sued for violations of antitrust law, as the packers appear to be taking advantage of the uncompetitive nature of the industry.

It is also true that meats represent only 1.1% of the CPI, so the 16% increase in prices over the last year is not boosting headline inflation that much. The UN Food and Agricultural Organization also estimates that global meat prices are up 17.6% since 2020, meaning domestic market power is not the only thing driving up prices. Antitrust actions in the meatpacking sector are simply not going to have meaningful impacts on inflation, even if they do significantly improve the meat market.

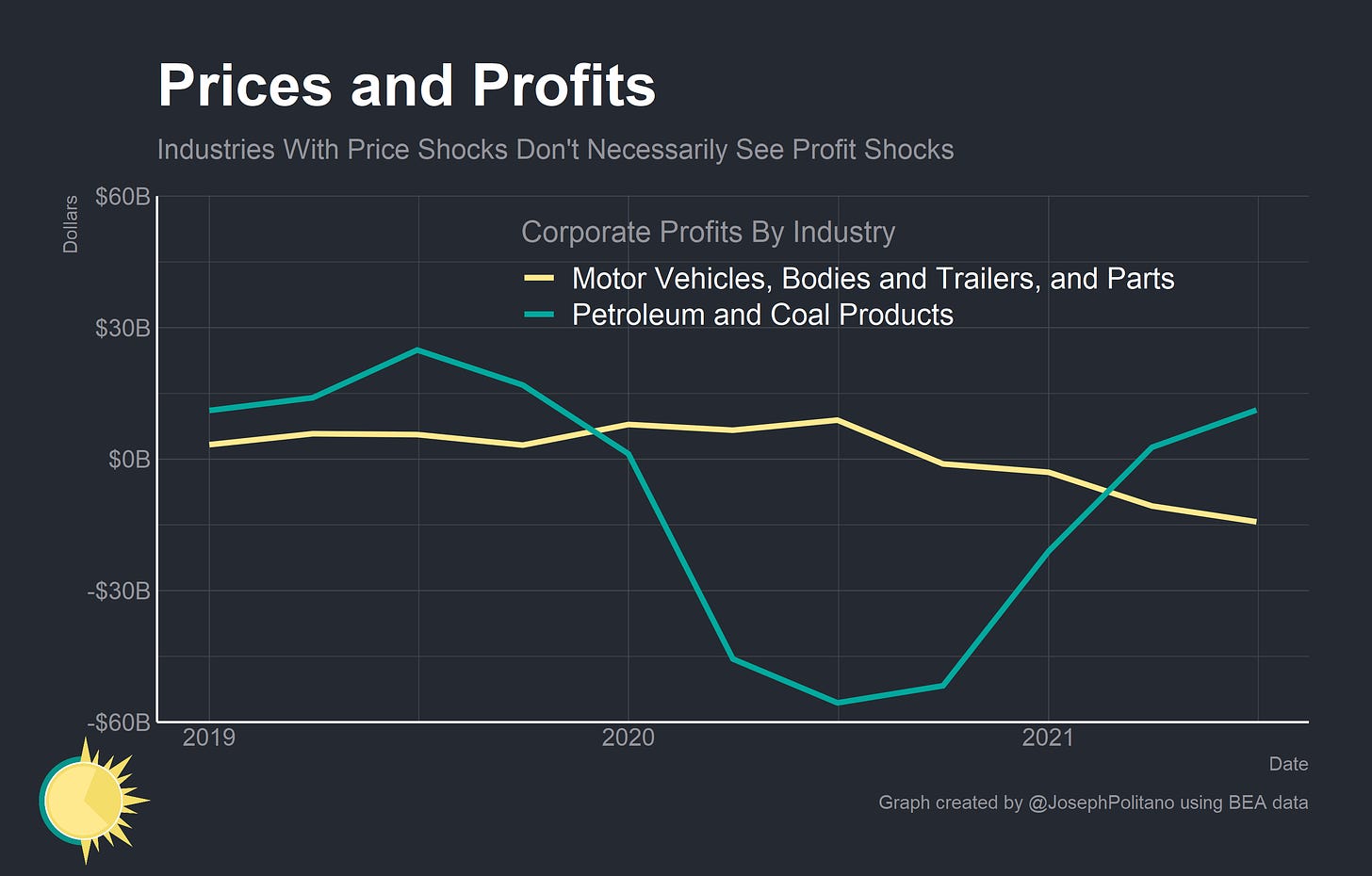

There are idiosyncratic goods that have experienced large price increases over the last year—energy, gasoline, and cars are the major ones—but these industries are not necessarily anticompetitive. Unlike American meatpackers, American carmakers and oil producers have not experienced a surge in profits despite the surge in prices.

The car industry has struggled with production issues throughout the pandemic, and the result has been a shortfall of more than 3 million vehicles. This has driven up prices, but has unsurprisingly left most carmakers with meagre profits as they work their way out of the SNAFU. Profits at General Motors and Ford are slightly below normal despite the jump in prices, and no automaker is experiencing massive profit growth as a result of the crisis.

Gasoline is mostly the same, but with some key differences. At the start of the pandemic large oil and gas companies began picking up distressed rivals in a wave of consolidation across the industry. Given the massive drop in oil prices at the start of the pandemic and long standing concerns about profitability and green transition risks, the majors imposed strict capital discipline and profitability requirements. The result has been a drop in output—but with good reason. The radical swings in oil prices in recent months reveal the risks that most oil companies are planning around.

Of course, oil is one area where oligopolistic market structure matters a lot—just not in a way that the US can do much about. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries Plus (OPEC+) controls approximately half of global oil supplies and sets explicit production targets to control prices (though there are intra-cartel conflicts). Changes in OPEC+ decisiomaking can dramatically affect short term inflation, but the Biden administration can’t simply use the Sherman antitrust act to break them up.

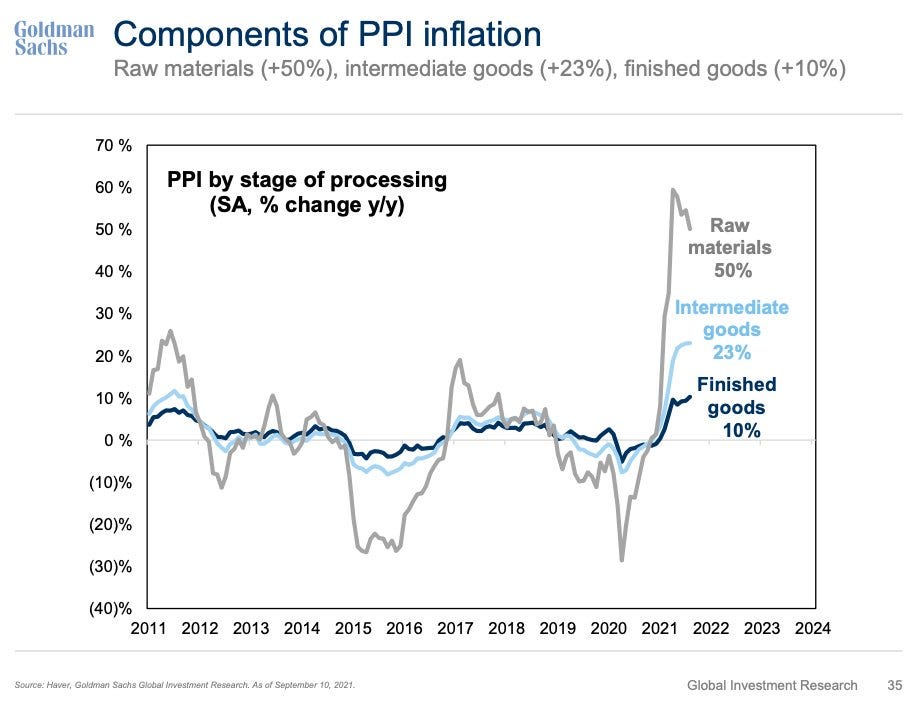

Finally, it is clear that firms are generally absorbing some of the rise in input costs caused by the pandemic. At each stage of production, firms are absorbing additional input cost increases and not simply passing them directly onto consumers. There is likely some double-marginalization, whereby separate firms markup their products through a combined supply chains in ways that would not be optimal if the supply chain was within a single firm, but it is hard to say that corporations are simply passing costs onto consumers or taking advantage of the pandemic to implement large markups.

Command and Control

The difficulty with wage-price controls and a wage board as you well know is that the God damned things will not work. They didn’t work even at the end of World War II. They will never work in peacetime.

Richard Nixon, 6 months before instituting wage and price controls

At the most extreme end of the scale, some economists have advocated for a regime of price controls to reign in inflation. I want to state in no uncertain terms that this is an extremely bad idea. From a practical perspective, COVID-19 is not the kind of mass-mobilization crisis that WWII was. At it’s peak, more than 40% of total economic output was going to national defense during the war, easily dwarfing any mobilization efforts the CDC or other federal agencies deem necessary today. The core problem throughout most of the pandemic was preserving household and business income in the face of shutdowns, not mobilizing resources for government consumption. The war came with extreme forced savings and financial repression mechanisms as well, both of which would be counterproductive in an economy where the principal goal is renormalizing consumer purchasing patterns.

In sectors that are truly experiencing transitory supply-shock-driven price increases—such as food, energy, oil, and vehicles—price controls will do nothing to solve the underlying issues. There is a shortage of millions of cars relative to pre-COVID trends—will price controls furnish new automobiles or buy time for capacity to catch up? What about gasoline? Are we banking that price caps will induce additional domestic oil output or somehow coax OPEC+ to boost their production targets? Will price caps satiate the across-the-board increase in demand for groceries or resolve production imbalances in food supply chains? Are we truly expecting Americans to accept government rationing for goods as critical as gasoline and food?

The government doesn’t have boundless knowledge of the quantities and cost structures of each product in the economy. It doesn't even have much of it, in fact. If it did, it could help out the companies that are shortchanged and stop inflation, or increase supply in non-neutral ways. But because it doesn't, and can't have enough information, policies to stop inflation are basically just guesses

Maia, “Will price controls end Argentina's uncontrollable inflation?”

Even more practically, the federal government does not have the capacity to implement price controls—the wartime Office of Price Administration and related agencies had 160,000 employees at their peak, which is more than any non-defense department has today. The amount of work necessary to develop, monitor, and enforce price controls in today’s economy is likely orders of magnitude more complex than it was in 1940, requiring extreme administrative intervention. The President would need congressional approval to begin price freezes—and it is unlikely that Joe Manchin will support that, to say the least.

The situations in which price controls work are extremely limited—usually only including natural monopolies and government administered services like healthcare or education. Nor are anti price-gouging rules, used with great effect in early 2020 to obtain PPE and medical supplies during the onset of COVID, easily applicable to years-long increases in commodity and food prices. Price controls on gasoline, used vehicles, or groceries are simply recipes for quickly developing robust black markets for all of those goods.

Claiming price controls are a good solution today’s inflation is politicking more than problem-solving. It simply is not a practical possibility, and even if it was there is no indication that it would solve the underlying issues. In most cases where headline inflation was stopped with price controls it was because the price controls bought time for substantive fixes, not because the controls themselves affected long run inflation. The reason there is so much chatter about price controls is because the truth—that closing and reopening the economy was a massive economic shock that pushed prices up—polls worse than claiming corporate greed causes inflation.

Conclusion

Fundamentally, Americans are earning about as much (in aggregate) as they would be had there been no pandemic. As long as nominal incomes remain on trend, inflation will subside.

That doesn’t mean the government should simply sit on its hands and wait for inflation to go away. There are concrete steps that the administration could take to combat short term inflation. For example, they could unwind some of the counterproductive tariffs that the Trump administration created. The Department of Commerce recently followed through with plans to double tariffs on Canadian lumber, to the detriment of homebuilders and homebuyers. Repealing the Jones Act, which bans non-American ships from moving goods between US ports, would alleviate some pressure on shipping prices. Keeping the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles running 24/7 should be viewed as a success, and the administration should further pursue boosting public infrastructure efficiency to help the economy. Antitrust actions can play a role as well, as long as it is acknowledged that they will only marginally tamper inflation and that their main benefits come from increase competition, investment, and innovation. As long as policies are grounded in the real causes of inflation, they can help alleviate the problem.

An earlier version of this post said that Dr. Weber was advocating for WWII-style price controls. While Dr. Weber studies the wartime price control measures, she clarified that she was only calling for debate and assessment of price control’s usefulness in the current situation, not the implementation of WWII-style or selective price controls. I apologize for the error.

Great post. Much appreciated.

Amazing stuff. Thanks for the read!