Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 10,400 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Programming Note: I got COVID this week—I’m staying home and feeling a bit better now but output might be affected depending on how I feel next week.

Last week, official data showed the second consecutive quarterly decline in us Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP)—output declined at an estimated 0.9% annualized rate. Two quarters of negative GDP growth is a colloquialized, unofficial heuristic for a recession, so it’s worth asking: is the US in the midst of one?

The situation is, frankly, complicated. Three months ago I discussed the first quarter US GDP report and said that while the headline number was negative underlying growth was still strong, technical factors were causing GDP numbers to vary wildly, and the GDP report was contradicting a variety of other economic data. The story is somewhat similar in this quarter—technical factors are causing GDP data to be unusually volatile and look especially bad—but the key difference is that there’s now an appreciable slowdown in the less-volatile parts of GDP and across other economic metrics.

There is, to put it mildly, good reason that the US’s official recession arbiters—the National Bureau of Economic Research’s (NBER) Business Cycle Dating Committee—don’t follow the “2 Quarters of Declining Real GDP Rule”—or even greatly privilege GDP data in their assessment of the economy. Quarter-to-quarter moves in GDP data are volatile in the best of times and have been doubly volatile in the pandemic—not to mention that all of the GDP reports we are currently dealing with are preliminary estimates that will be revised when more complete data sources are available. Nevertheless, there are important indicators embedded in the GDP data that—coupled with narrower, more precise economic data—paint a picture of an economy that is slowing but has likely not entered into a recession.

Damage Report

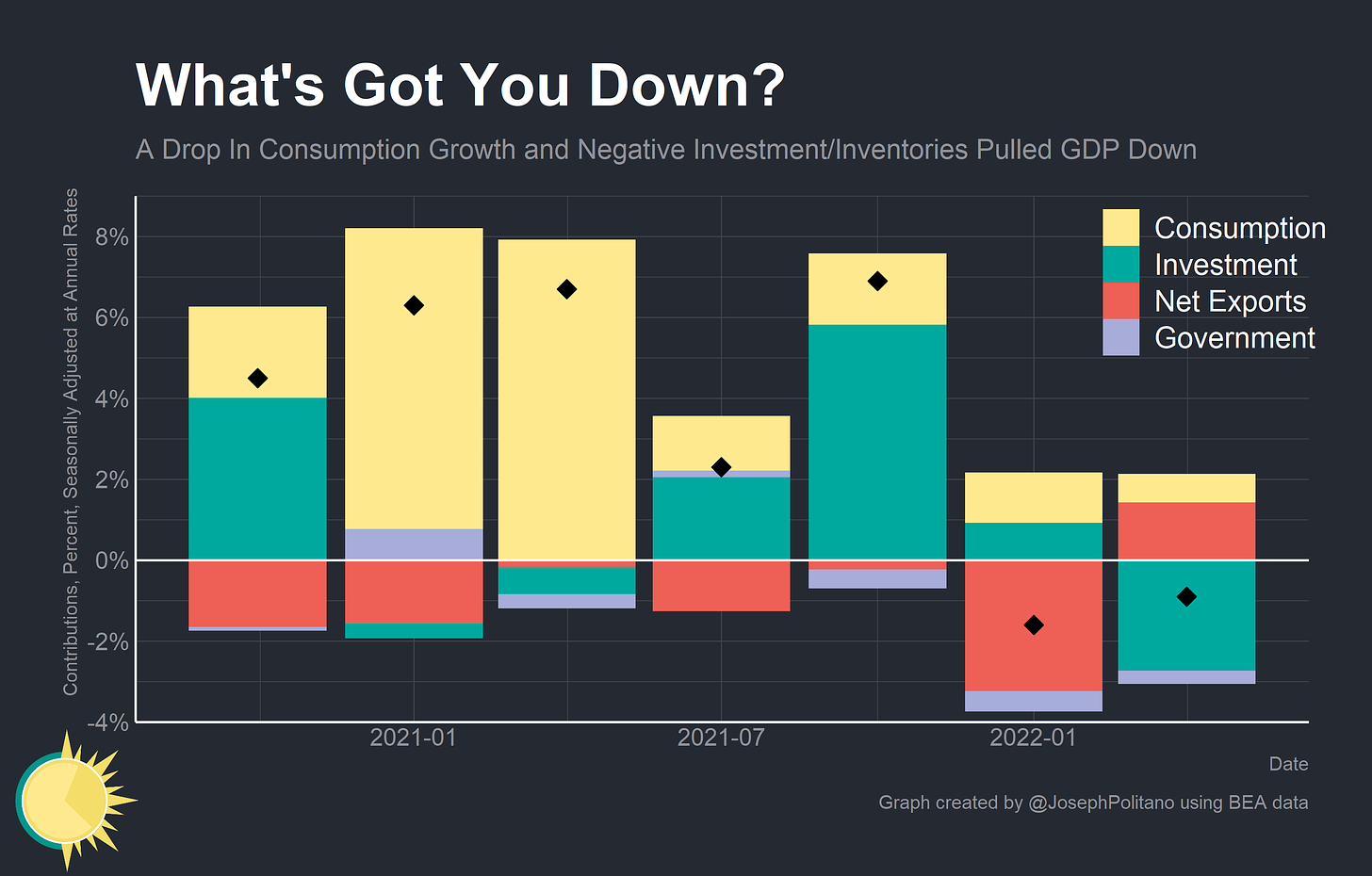

In Q1, the large drop in GDP was caused by a massive decrease in net exports and a smaller positive contribution from investment. In Q2 the contribution from net exports flipped positive for the first time since the second half of 2020 and investment’s contribution dipped negative for the first time in a year. That massive decline in investment was mostly driven by a -2% contribution from inventory growth alone.

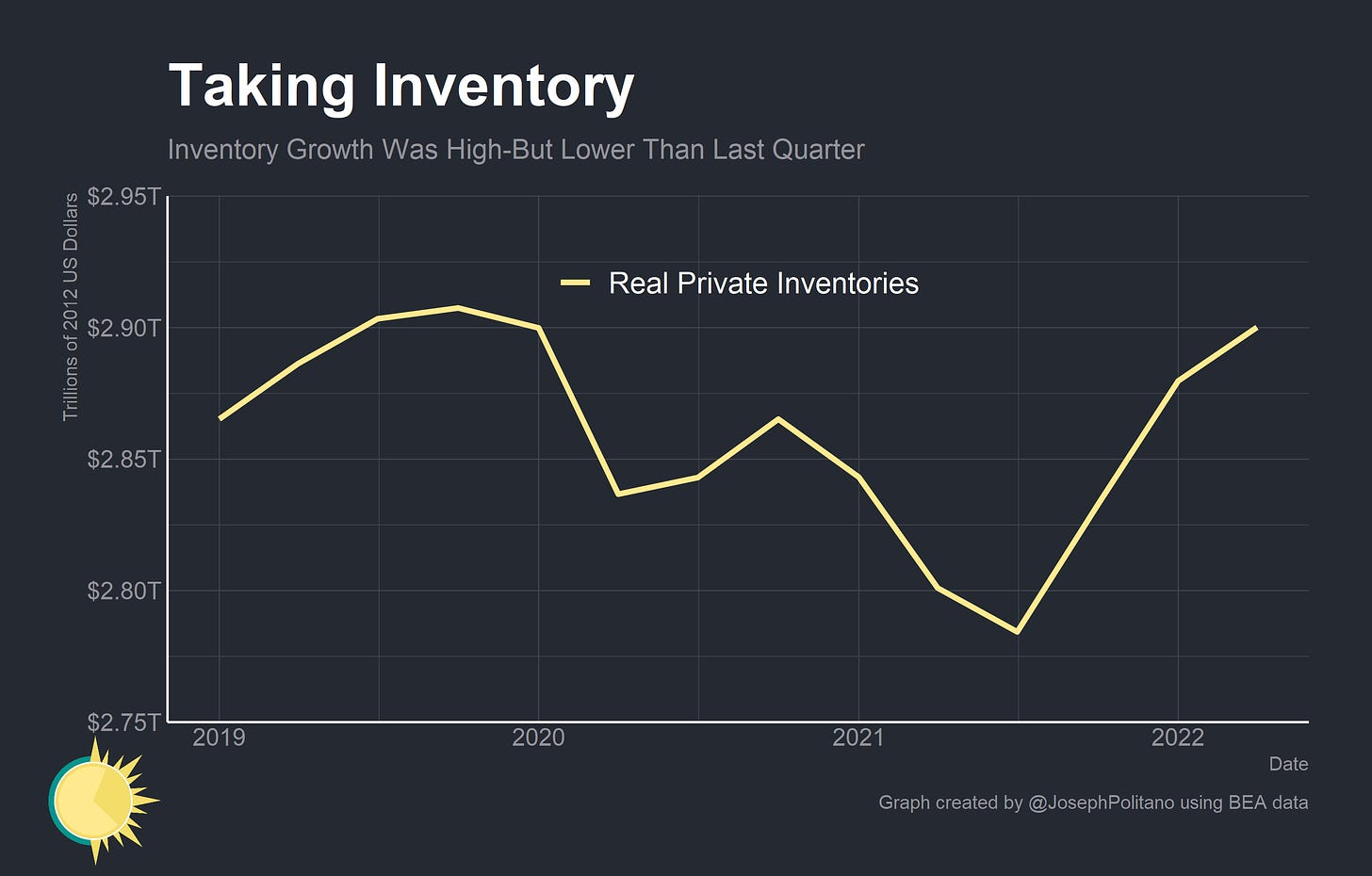

As a bit of background, growth in private business inventories are counted as investments in the GDP data. If Georgia peaches are harvested in August, canned in September, and sit in the company’s warehouse until December, then GDP data accounts for the peach’s production in August as a boost in private inventories. That example often gives businesses a little too much credit and the data a little too much credulity—especially in the pandemic, inventory buildups and drawdowns are as much the product of supply chain fluctuations as they are an intentional business investment. That doesn’t mean inventory data is fake—in recessions, inventories are often drawn down significantly as businesses lose confidence to resupply, hence indicating lower production—but they are messy. Even messier, what truly matters to GDP is not the change in private inventories but the change-in-the-change in private inventories, the second derivative.

In Q4 of 2021 inventory growth was massive due to intense holiday restocking and the stabilization of motor vehicle inventories—so the total contribution of inventories to GDP was 5.32%. In Q1 inventory growth was still massive, but marginally lower than Q4—so the total contribution of inventories to GDP was -0.35%. In Q2 inventory growth slowed down significantly but remained high by pre-COVID standards—so the total contribution of inventories to GDP was -2%.

There’s a bit of perverseness to the entire inventory ordeal—rapidly rising inventories are partially indicative of weakening demand for consumer goods (Walmart and Target are both complaining about excess inventories), but GDP data is being dragged down because inventory growth isn’t fast enough. Either way, inventories have been so volatile during the pandemic that a clear analysis of GDP data requires looking at them critically.

On the flip side, shifting export dynamics helped push up GDP this quarter—after dragging GDP down last quarter. Q1’s drop in next exports came from a mix of decreasing exports to east Asia amid the imposition of strict COVID lockdowns in China, a jump in imports caused by increasing port throughput, and seasonal adjustment factors. Q2 saw an inversion of some of those factors—particularly the surge in real imports caused by seasonal factors and a jump in port throughput. That brought net export’s contribution to GDP up to 1.43%—helping to counteract the negative contribution from inventories.

There’s also something weird going on under the surface of US output data. Gross Domestic Product, which determines output by measuring the real value of production, and Gross Domestic Income (GDI), which determines output by measuring the real value of income and spending, are supposed to arrive at equivalent numbers for the size of the US economy. But since the pandemic—and especially recently—GDI has been much more optimistic than GDP. We won’t get new GDI data until the end of August—but in the meantime, Matt Klein has some great (paywalled) pieces walking through the complicated set of factors that could be causing this gap. Suffice to say that it’s possible for measurement error in GDP calculations to be causing significant underestimation of the size and growth of the US economy.

Let’s not get overly optimistic, though—there are some serious, harder-to-deny signs of a slowdown across the output data that point to an ongoing economic slowdown or possible contraction. The starting point is the ongoing energy crisis exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Real US consumption of gasoline declined 5% over the last two quarters and now sits 8% below pre-COVID levels—lower than at any point between 2001 and 2020. Prices have abated a bit thanks to releases from the US’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve, weaker demand from China, and some upticks in drilling and refinery output, but they remain high compared to pre-COVID levels.

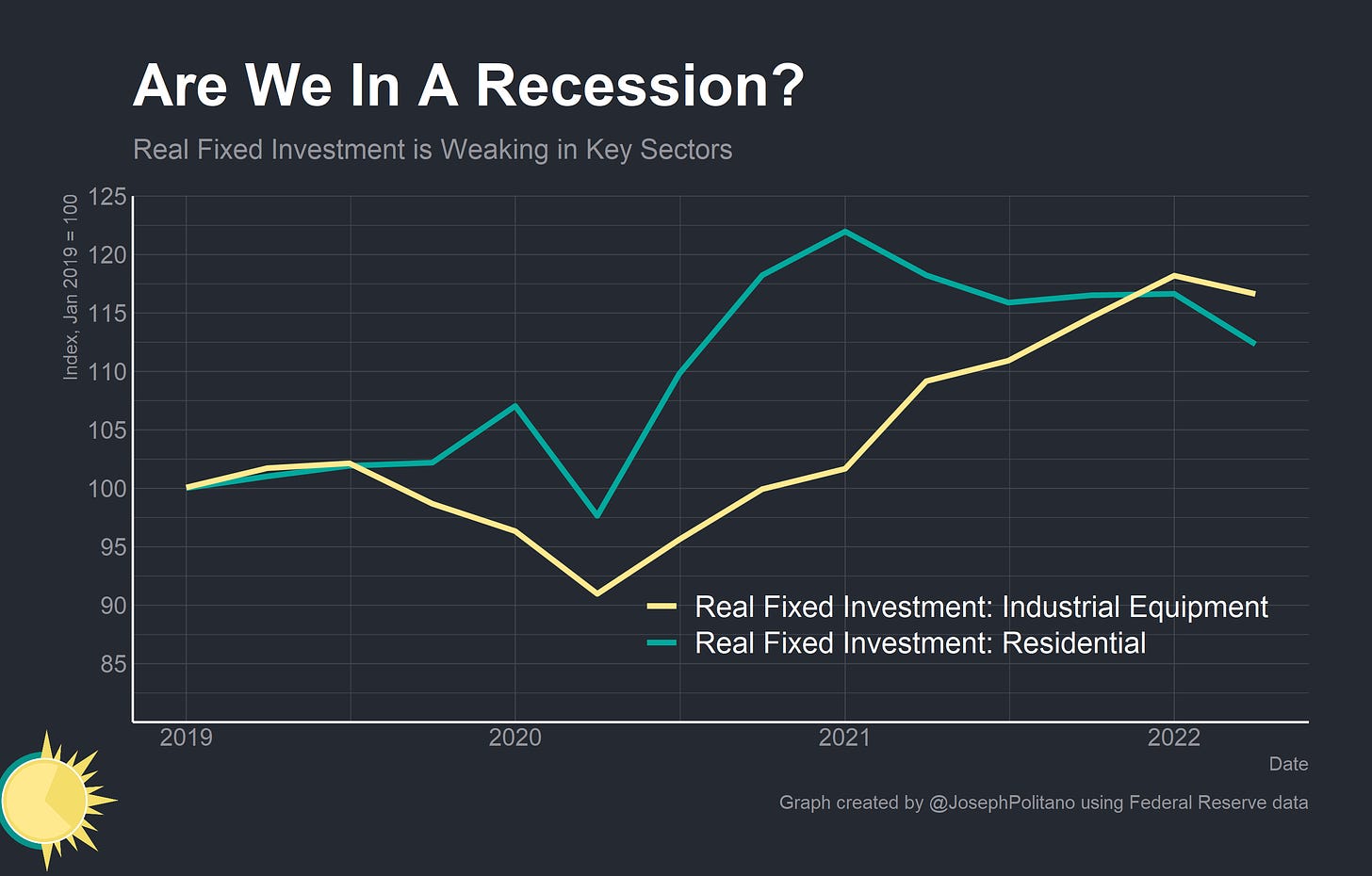

Fixed investment also suffered in the second quarter—investment in industrial equipment sank for the first time since the start of the pandemic and residential investment dropped as mortgage rates negatively impacted housing starts. Drops in fixed investment are always critical to watch, as even slight declines in consumption can have larger ripple effects through the subsequent drop in investment.

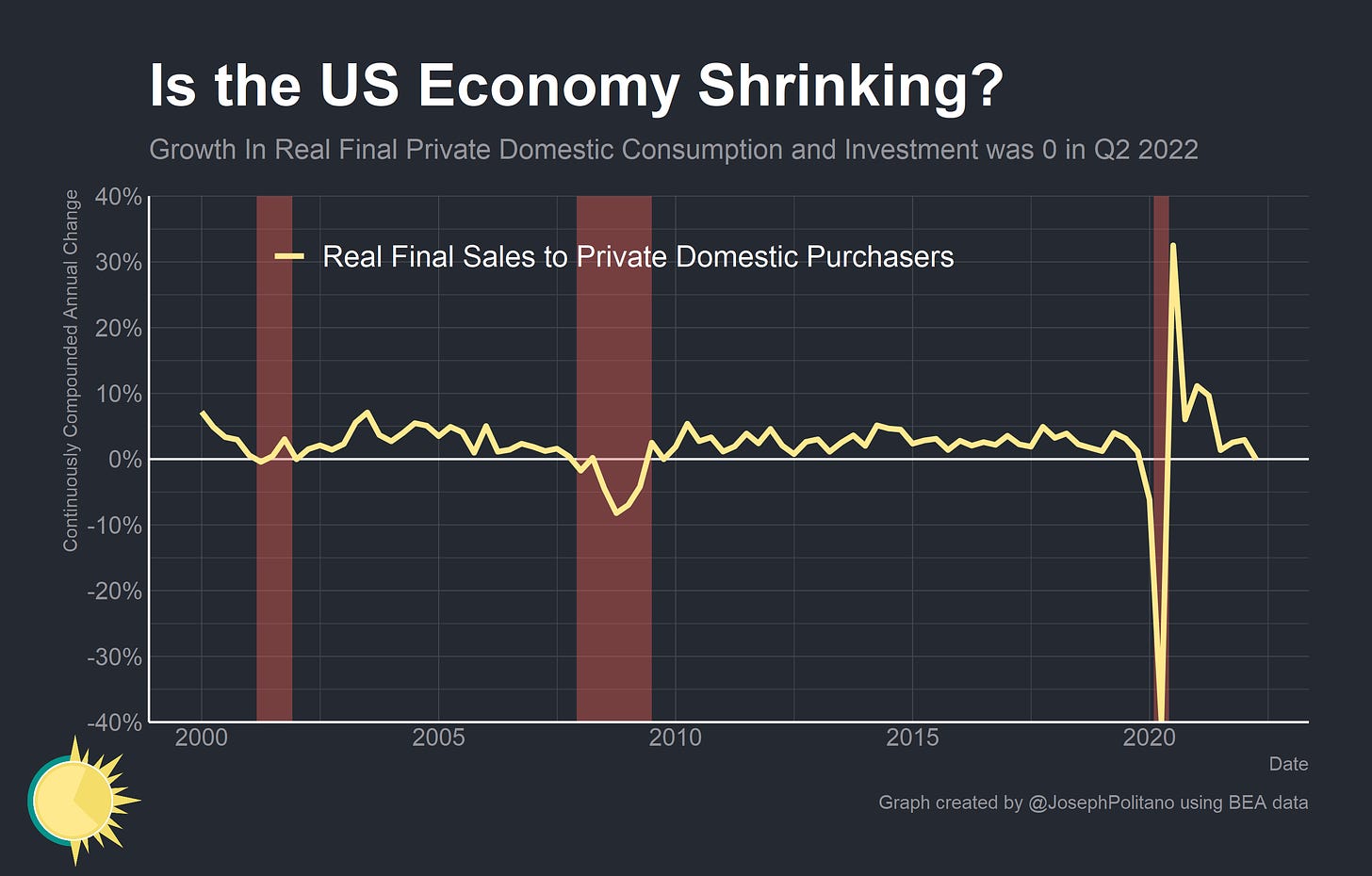

GDP data is also showing an extremely rare stagnation in a complex but important metric—Real Final Sales to Private Domestic Purchasers. This essentially measures total consumption and fixed investment by private American consumers and businesses—so it excludes volatility in net exports, inventories, and government spending. As a result, it tends to only decline during periods of significant slowdown or recessions—as in 2001 and 2008. In Q2 growth in this metric hit zero for the first time since the start of the pandemic as a drop in fixed investment offset marginal increases in personal consumption. That may be the most worrying metric from this quarter’s GDP release.

Dating the Business Cycle

Okay, but enough of the serious data analysis—the real drama surrounds whether the US is officially in a recession or not. People are abnormally wedded to the idea that two quarters of negative GDP defines a recession— which just isn’t true in the US. But the debate got out of hand to the point that the White House Council of Economic Advisors felt the need to weigh in, Wikipedia was forced to temporarily restrict editing of its “recession” page, and it became virtually impossible to have a nuanced discussion of this online.

Fundamentally, I do not find the question particularly interesting. The NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee determines when a recession is in the US, and they do not just follow the 2Q rule, because any single-data-point test for a recession will inevitably be flawed. The 2001 recession did not have two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth, nor did the 2020 recession—and there is one instance of two quarters of negative GDP growth occurring without an official recession.

But the Business Cycle Dating Committee is mostly interested in an academic definition of a recession—“what months, precisely, did the economy enter and exit a contraction so that all academic economists can sort their recession charts and papers around the same dates?”—not questions of “is the economy doing well?” Officially, the US exited the 2008 recession in June 2009—when the unemployment rate was still 9.5% and rising. The COVID recession officially lasted only from February to April 2020—when the unemployment rate was almost 15%. The committee is not making a declaration of “actually the economy is great” by saying that we aren’t in a recession.

And the committee was never going to immediately make the determination—they take nearly a full year on average to declare a recession, which is sometimes faster than it would take to get completely revised GDP data. So if an official designation of a recession won’t change anything going on in the actual economy and, if it comes, will come too late for it to matter for political point-scoring, all this technical debate amounts to is a lot of wasted ink.

But okay, given that we want to predict whether the committee will declare a formal recession, what will they be looking for? Here’s what they say are the data points they look at when determining the start of a recession, and how they consider them:

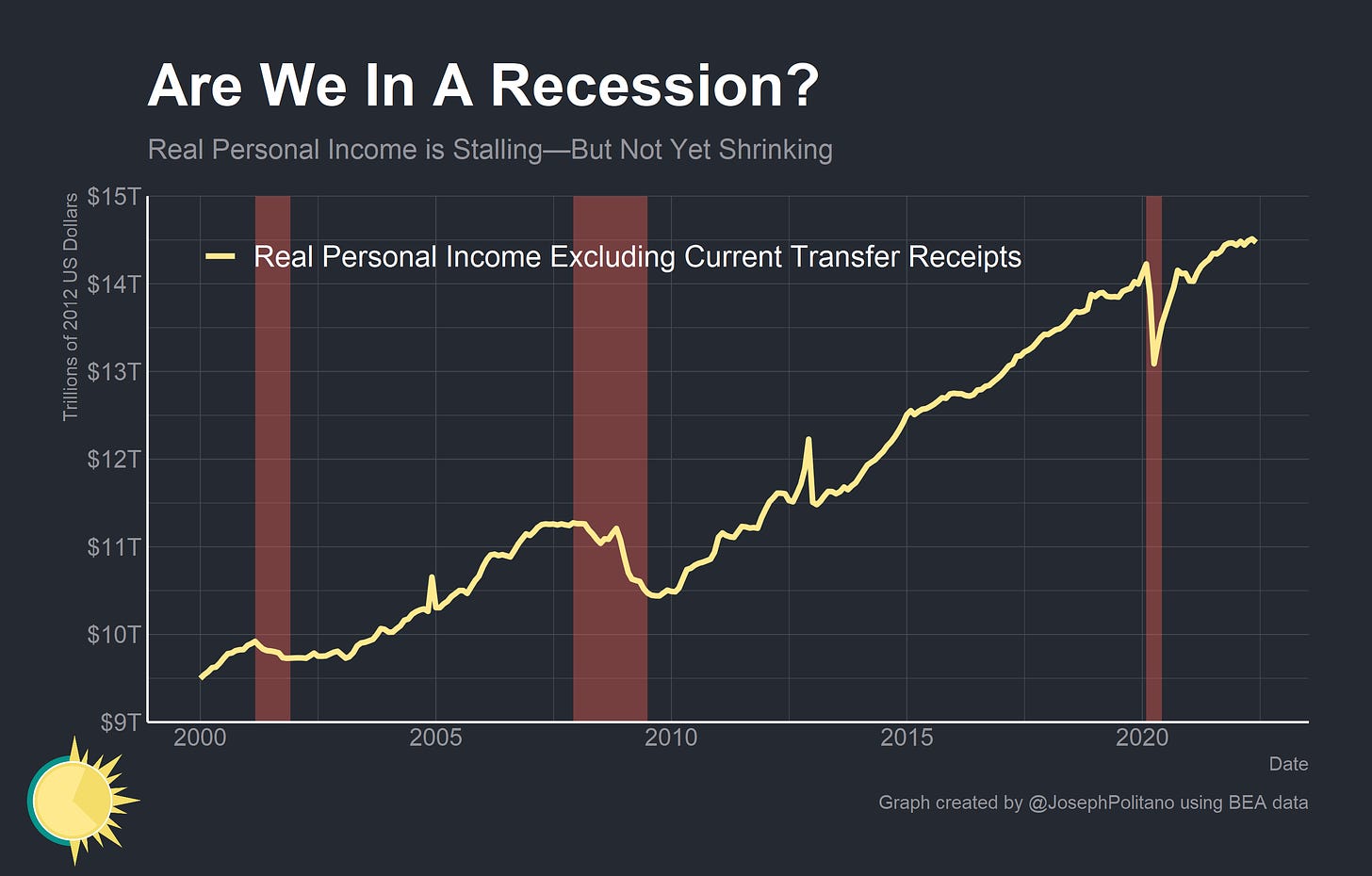

These include real personal income less transfers, nonfarm payroll employment, employment as measured by the household survey, real personal consumption expenditures, wholesale-retail sales adjusted for price changes, and industrial production. There is no fixed rule about what measures contribute information to the process or how they are weighted in our decisions. In recent decades, the two measures we have put the most weight on are real personal income less transfers and nonfarm payroll employment.

Let’s start with real personal income less transfers. It has stalled significantly over the last 9 months but has not shrunk. That much more closely matches the experience during the 2018 and 2016 slowdowns rather than the 2001 and 2008 recessions. With more up-to-date estimates of wage growth running extremely hot even as commodity prices fall, real income could pick up in the coming months. Dividend income is also running unusually low (in this case, because corporations are distributing a smaller share of their profits back to shareholders and instead choosing to maintain rainy day funds throughout the pandemic), but the distribution of these corporate savings could therefore also boost real personal income.

In truth, though, the main metric of a recession is employment. Real income, consumption, and retail sales tend only to fall when employment levels sink—and employment levels have not dropped off significantly over the last two quarters. In fact, the first quarter of the year saw significant growth in both the household survey (which asks people if they have a job) and the establishment survey (which asks businesses how many people work for them). The second quarter was much more mixed—household survey employment data was stalling even as we saw robust growth in the establishment survey (for what it’s worth, I tend to favor the household survey as a real-time measure). Either way, there is definite job growth across both surveys over the last six months, something that is extremely rare during a two-quarter GDP drop.

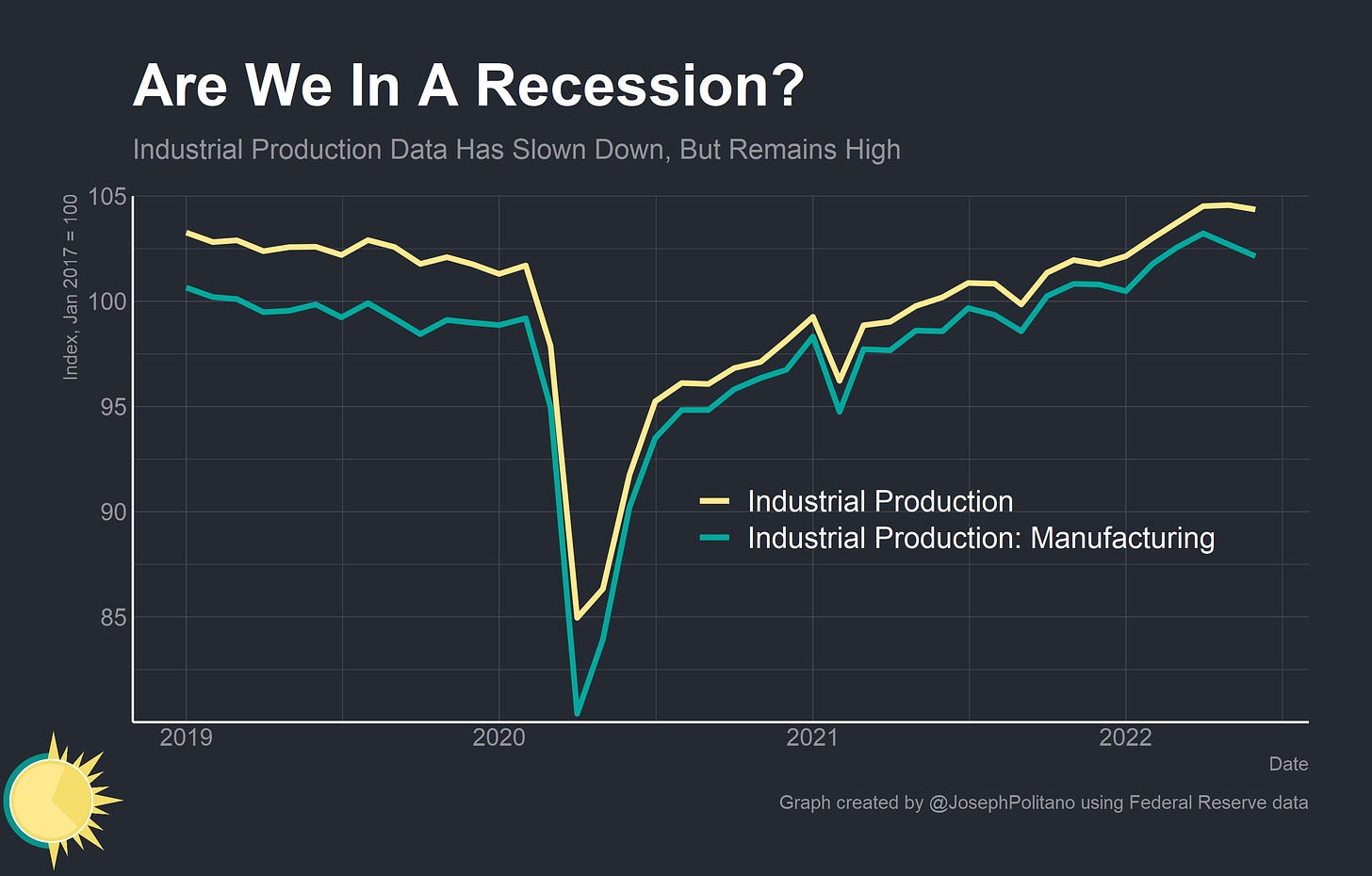

Industrial production metrics also remain fairly strong with significant growth through the first quarter—even if there is an appreciable slowdown in the second quarter. Combined with manufacturing surveys from the private sector and the Federal Reserve, there appears to be a worsening of business conditions for goods producers over the last couple of months. Conditions in the service sector seem less bad as consumers rotate some of their spending from goods to services, but there are similar weaknesses. Time will tell if they decline further, but current deteriorations in business conditions are not likely enough to justify a recession call.

Conclusions

When I wrote about the Q1 GDP numbers back in May, I said that the big lesson should be how bad of an indicator quarter-to-quarter real GDP has been throughout the pandemic. Unfortunately, I think since then the proliferation of nuance-free analysis of headline GDP numbers has only increased.

It is possible (and please note this is an exercise, not a forecast) that Q3 could see further deterioration in real consumption and investment as interest rates continue to rise. Despite this, GDP could be positive if an additional push from inventory growth (especially motor vehicle inventories) materializes—masking the true size of the slowdown.

There are a variety of non-GDP data points that are essential components to evaluating recession risks including initial unemployment claims (which are trending upwards and just above historical lows), corporate credit spreads (which are trending downwards for the first time in several months), employment levels (which are stalling), and domestic energy costs (which are high but decreasing). GDP data is important—and is now in closer agreement with other data sources that a slowdown is occurring—but it should not be the final word in economic analysis.

Great article Joseph. You should jump on The Closingbell Show to discuss! We have 60,000+ in our community who'd love to learn from you. We recently had on Alex Morris, Ayesha Tariq and Tyler Okland :)

That sucks about covid. I hope you feel better real soon!

I fell ill with covid last week. One day TKO'd, followed by three days of blowing my brains out my nose. On the fifth day I woke up and almost all my symptoms had blown away ('s not a good pun, sorry). There's no one-size-fits-all disease trajectory, but that's how it went for me. Lots of (attempted) sleep and deliberate hydration seemed to help.

Please take care!