Can The Housing Market Stabilize?

After a Historic Rise in Mortgage Rates, Can America's Housing Sector Hold?

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 21,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

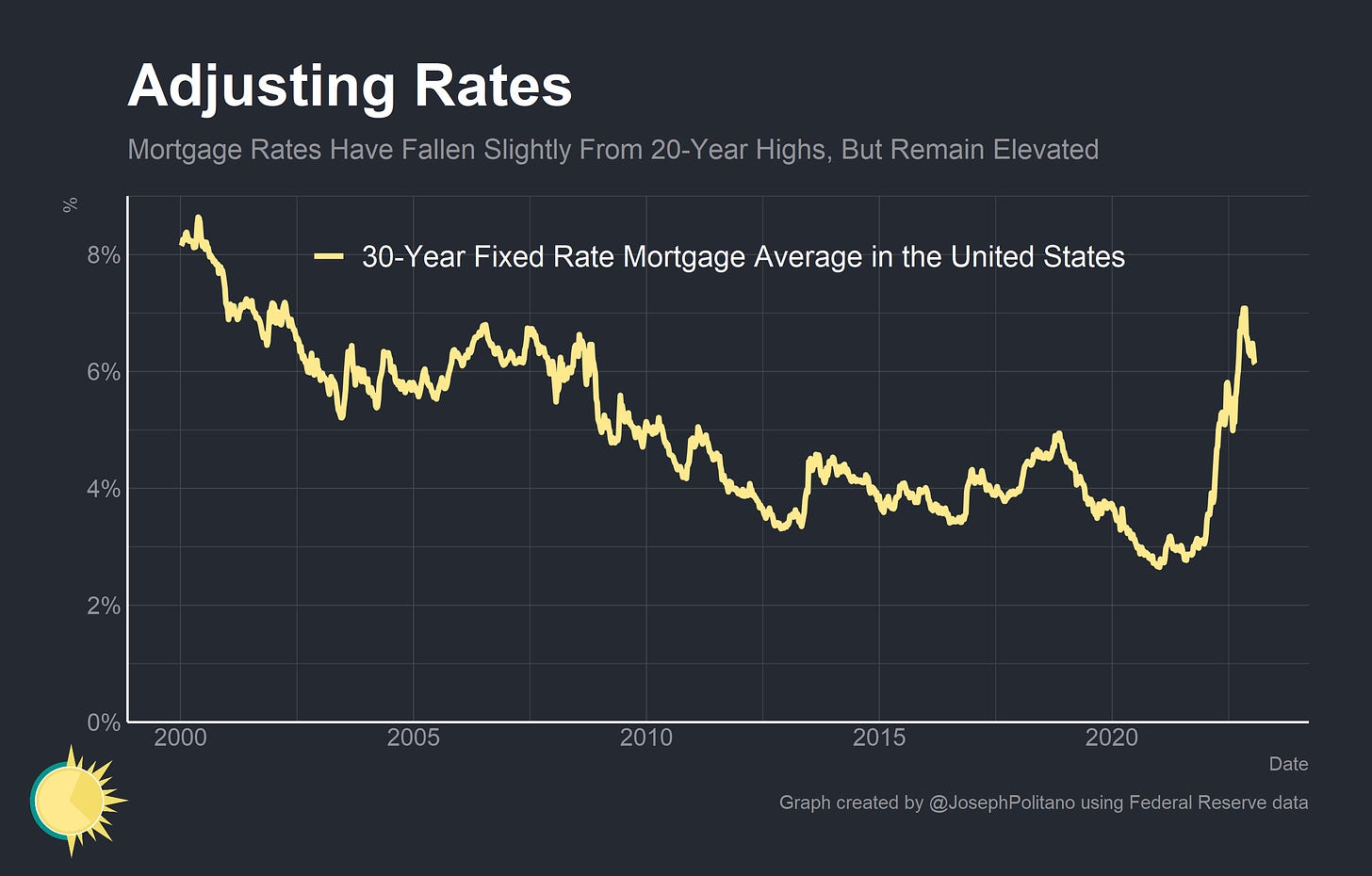

In the United States, rising interest rates usually hit the housing sector the hardest. Most of America’s housing, both new and old, is single-family owner-occupied units, for which market and construction sentiment is highly dependent on mortgage rates. So when the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates earlier this year and 30-year fixed mortgage rates surged to 20-year highs, the outlook for the housing sector turned especially grim.

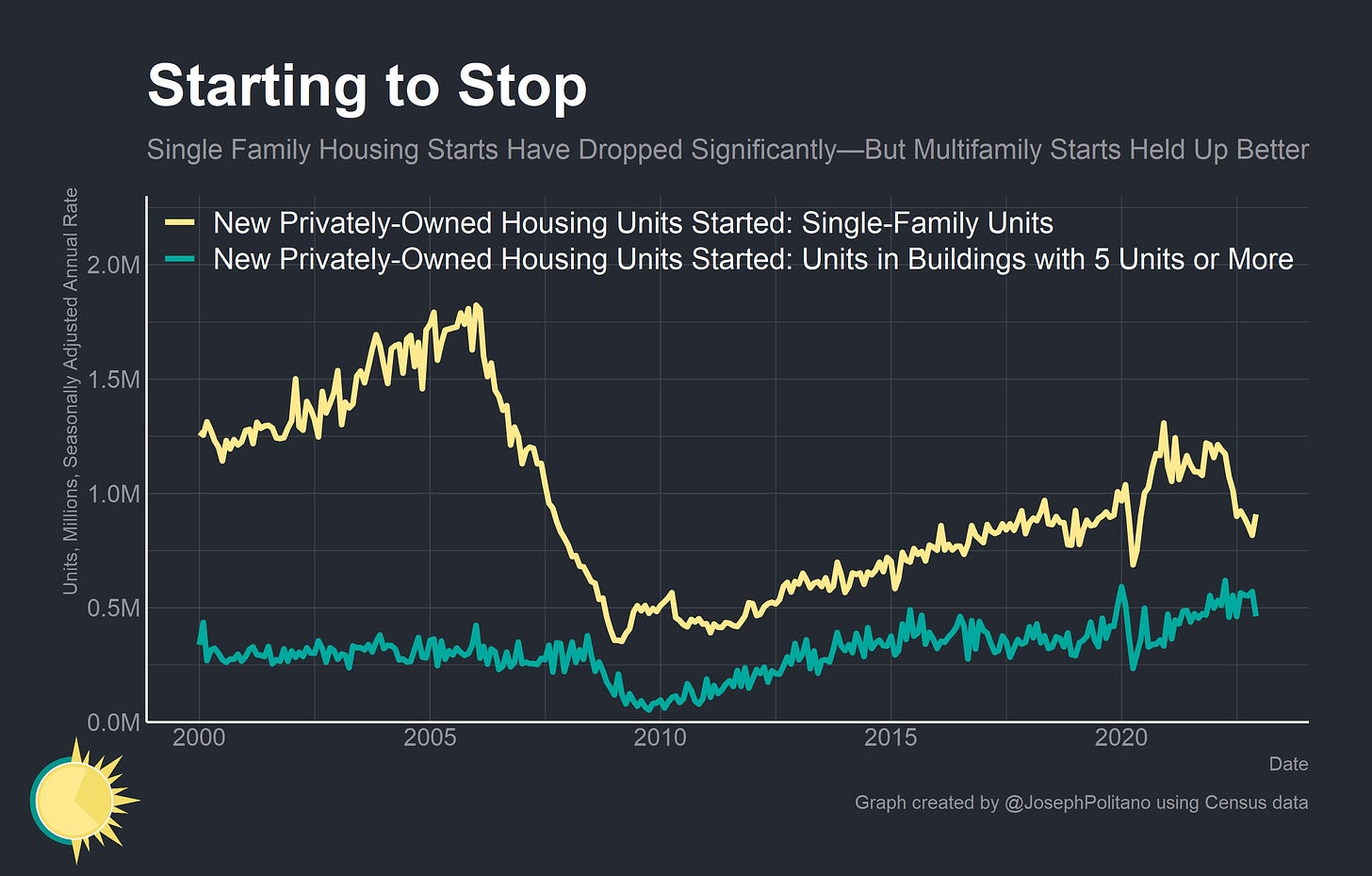

Throughout last year, those grim forecasts slowly became a reality. Single-family housing starts fell nearly 35% from their 2021 highs and real private fixed residential investment has dipped well below pre-pandemic levels. Housing prices look to be cooling or actively declining already, and homebuilder sentiment has drastically deteriorated. But in other ways, the slowdown hasn’t quite been as bad as anticipated—residential construction sector employment has held up remarkably well, and multifamily starts were at the highest level since 1986.

Recently, as monetary policy expectations have become less volatile and macroeconomic downside risks less pronounced, mortgage rates have started to retreat—but that still leaves the housing market in a nearly unprecedented place. Rates are still higher than at any point in the last decade, the backlog of unfinished units is still at historic highs, prices remain elevated, and while construction sentiment has picked up a bit off the lows the housing market is still trying to adjust to significantly higher mortgage rates. But given housing’s importance to the American (and global) economy, one critical question still remains: can the housing market stabilize, or is the worst still ahead?

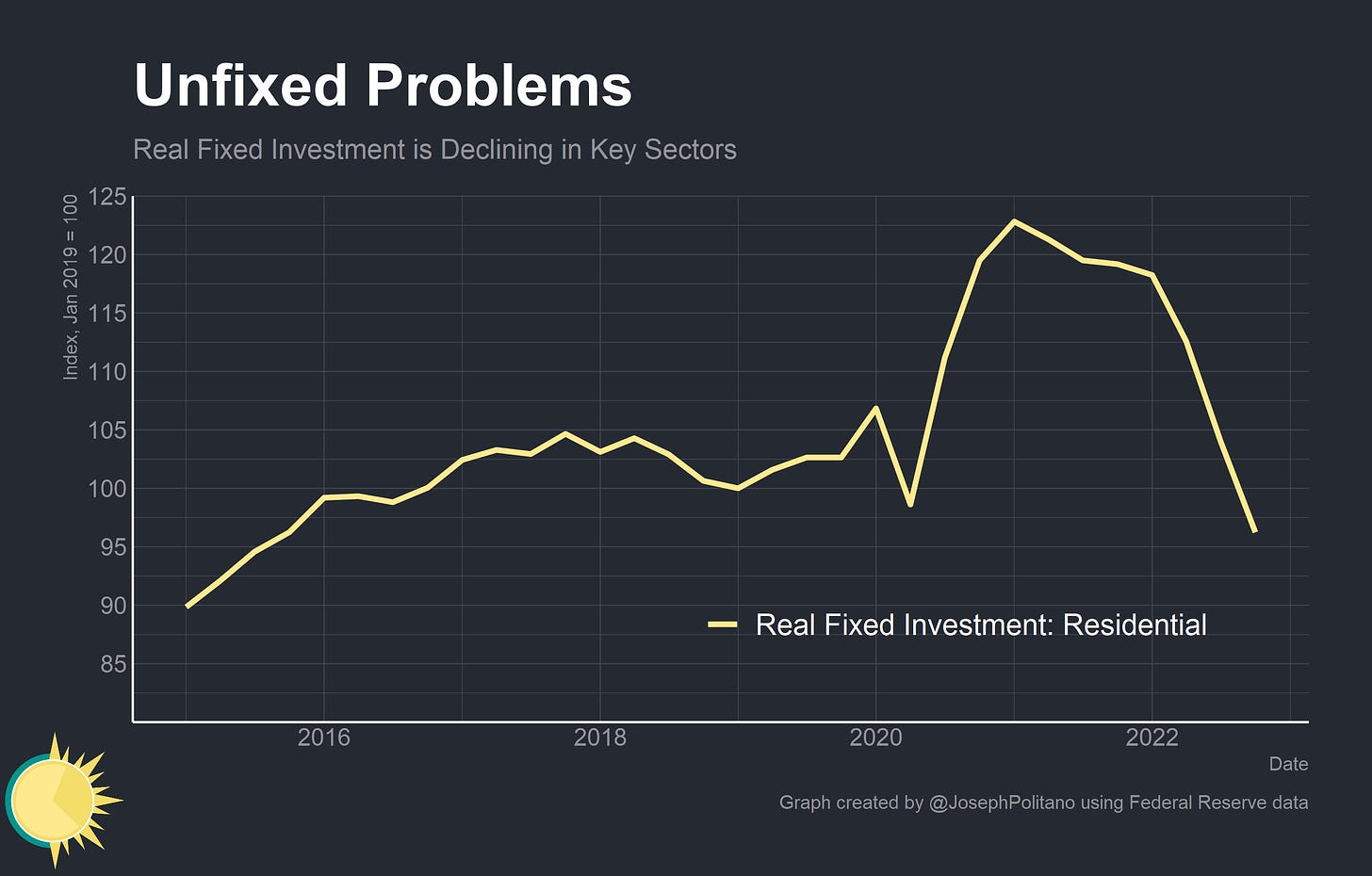

Starting Down, Finishing Up

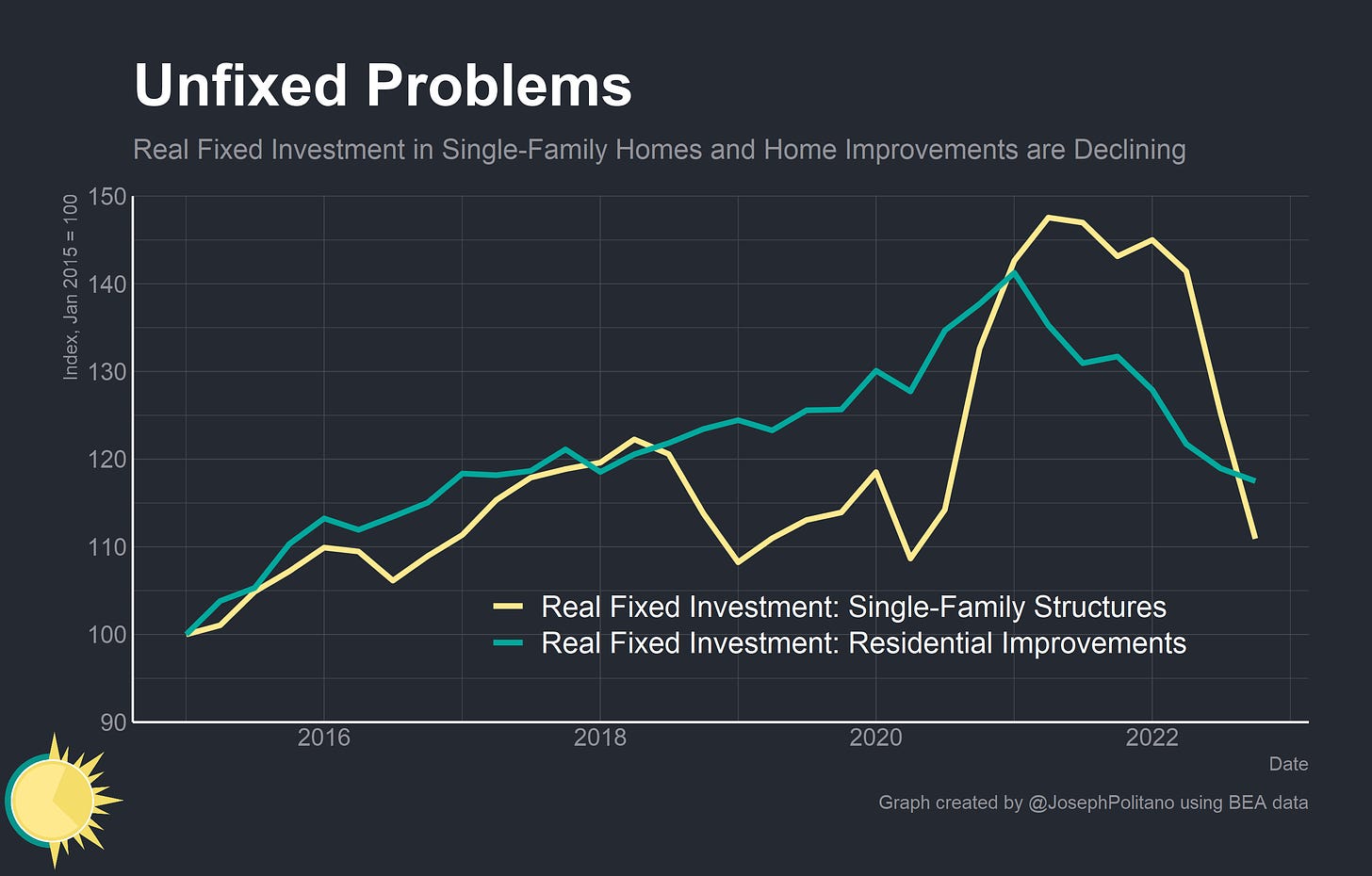

This Thursday’s Q4 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) report gave us a deeper look at just how historically rapid this housing downturn has been. Real private residential fixed investment—which measures the inflation-adjusted value of output directed towards housing construction and improvements—has fallen 20% throughout the year and now sits well below pre-pandemic levels. In fact, it now sits at the lowest level since the end of 2015, and about on par with early 2008 levels.

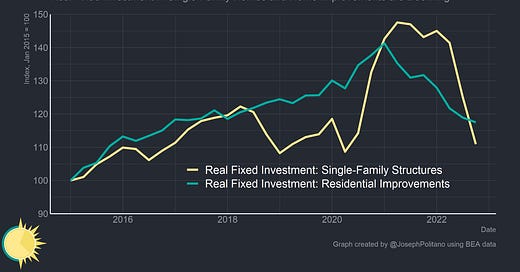

The two biggest drivers of this drop have been a total collapse in single-family structures and in residential improvements—both sectors that had demand pulled forward strongly during the early part of the pandemic. Lower mortgage rates, a rise in re-suburbanization driven by remote work, and homebound consumers led to a surge in demand for both home renovations and new single-family housing starts that is now rapidly abating.

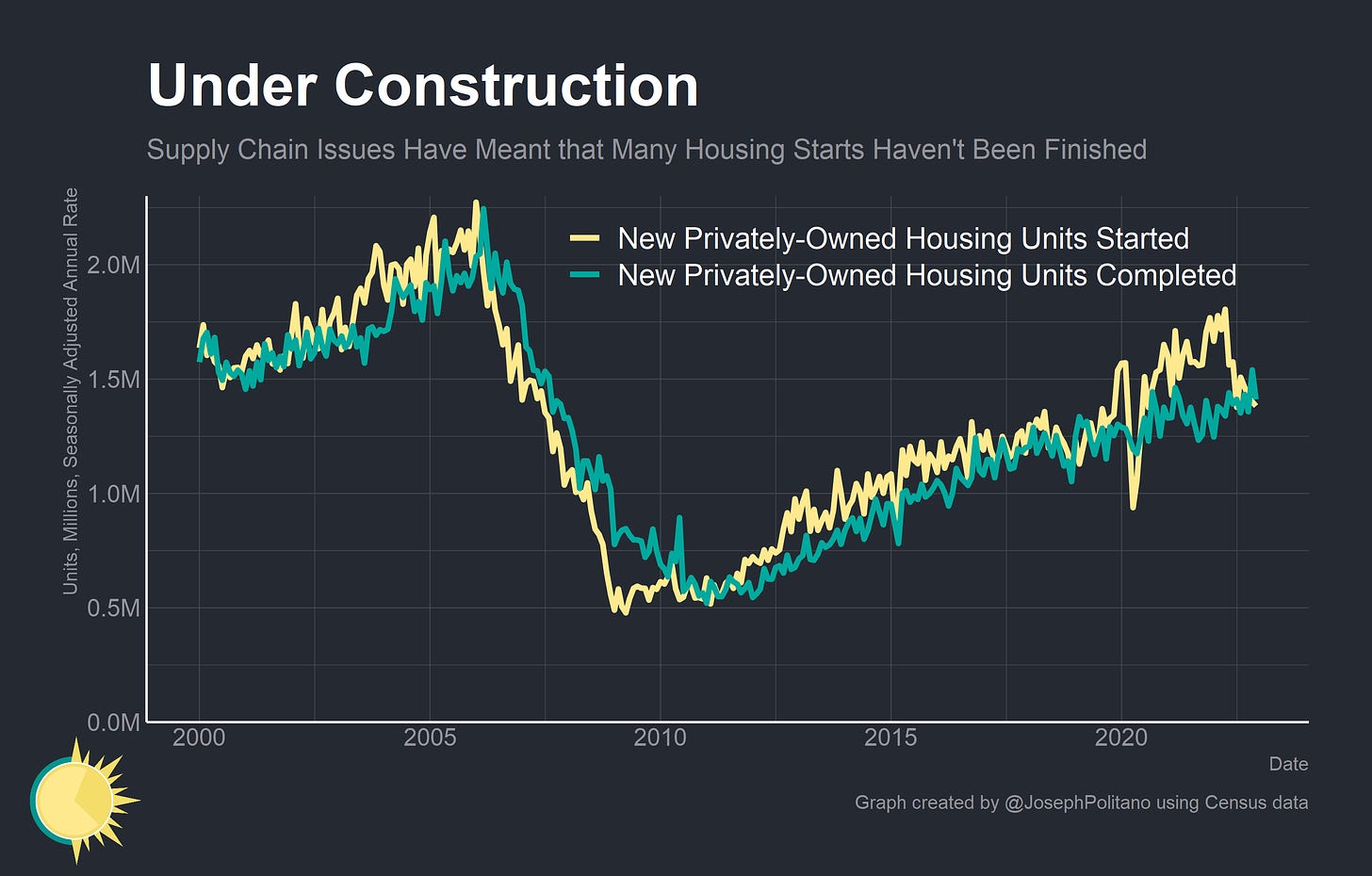

Still, the key dynamic that currently separates this housing cycle from previous downturns is the latent strength in the housing market driven by the pull-forward of demand. Housing starts have outpaced completions by a historic margin over the last two years as material and labor shortages extended construction times and kept projects from finishing. In fact, if you only had completions data to look at, you would barely notice either the pandemic or the ensuing rise in mortgage rates—the volatility in housing starts has hardly made a dent in final housing output, which still sits at practically a post-2008 high.

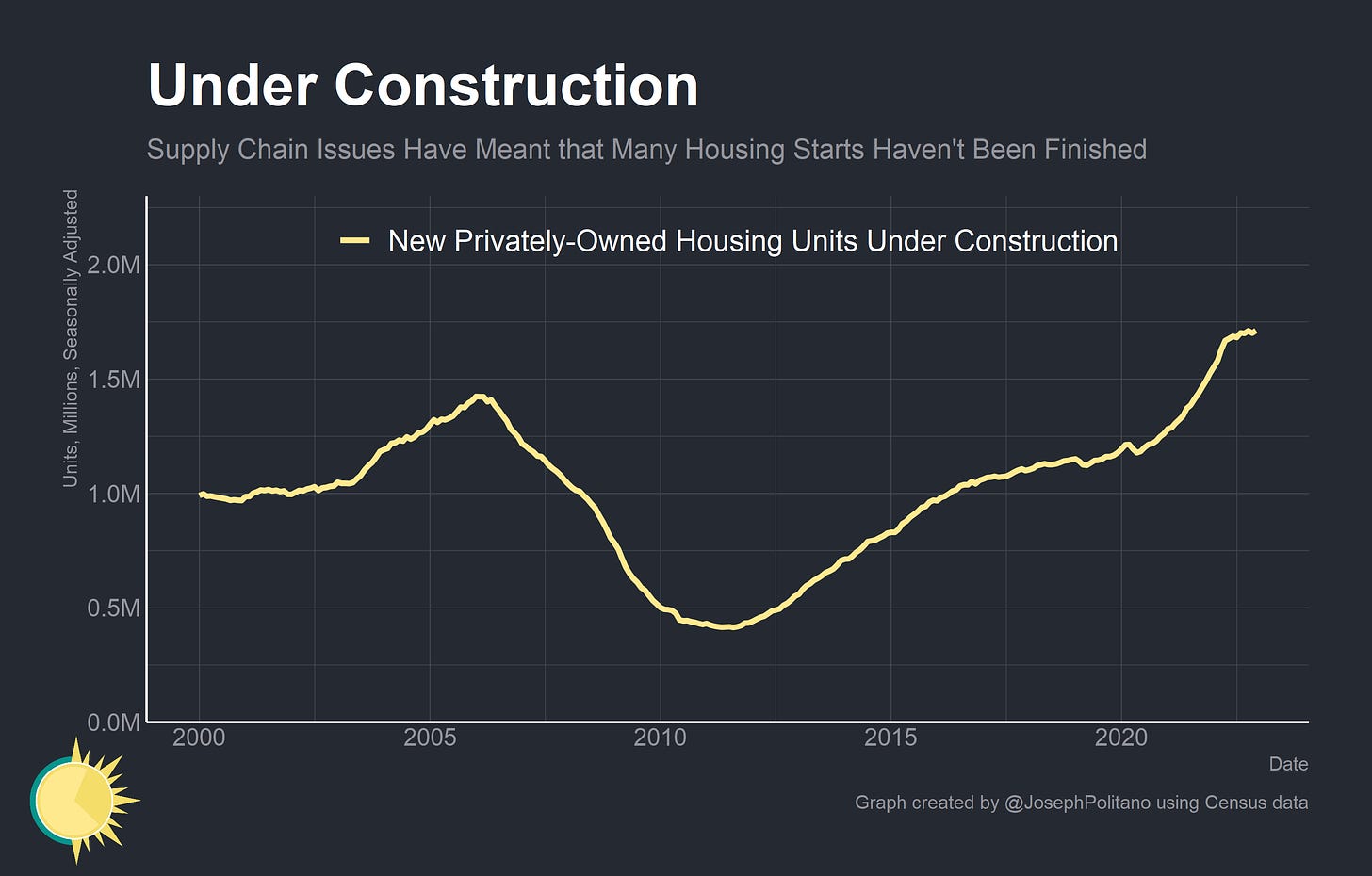

That pull-forward of demand means the number of units under construction still remains near all-time highs despite the rapid downturn in new housing starts. In other words, the US hasn’t yet made a dent in the backlog of new housing units that started growing in 2020. The downturn in starts has, however, made a bit of an impact slightly earlier in the production chain—the number of housing units permitted but not started has fallen to 285,000, down from a peak of 302,000 in October.

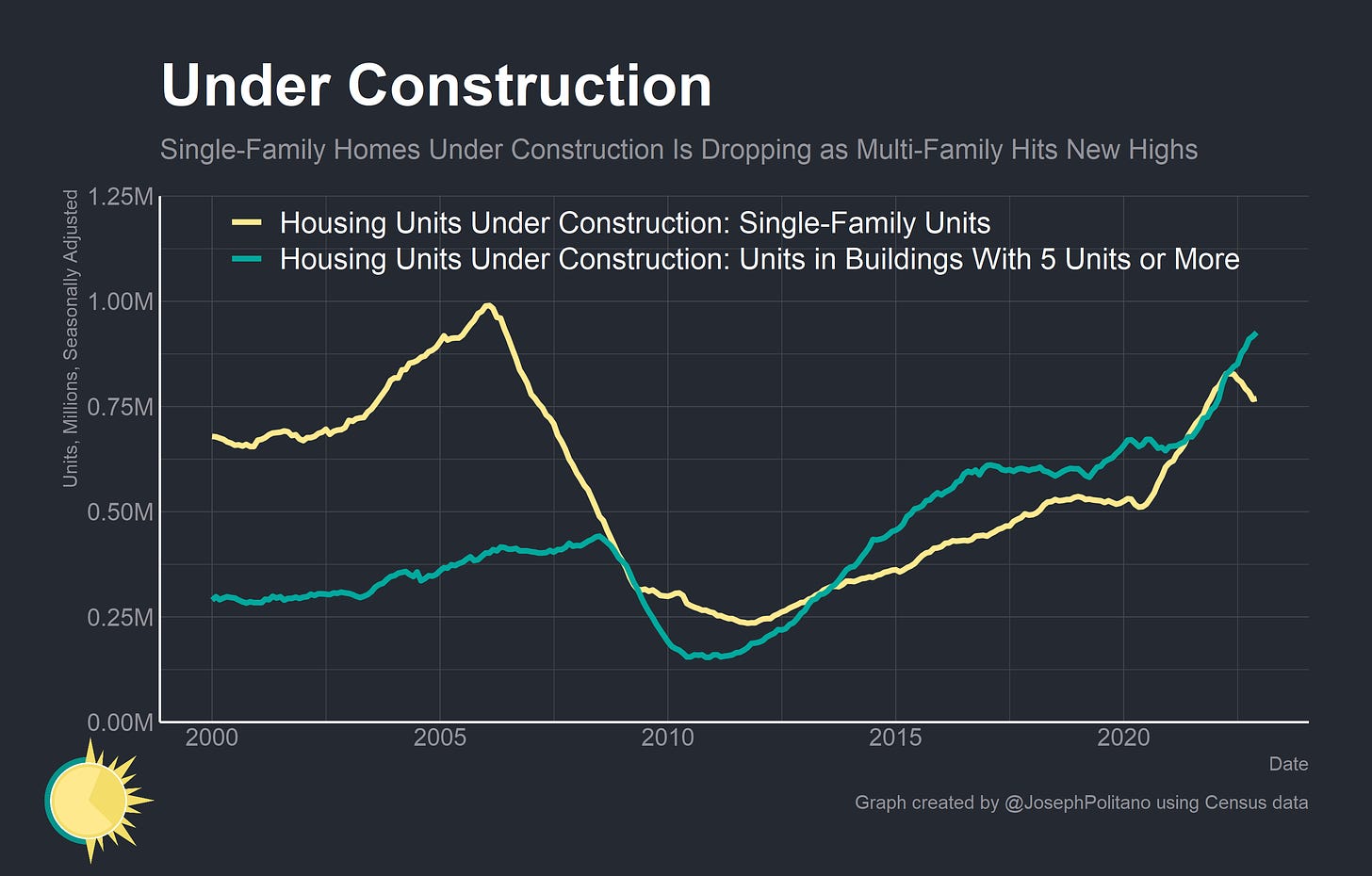

Most of the backlog consists of multifamily housing projects, with the number of units under construction in buildings with 5+ apartments rising 35% since the start of the pandemic to a new record high. The divergence in recent months is notable here—the number of single-family units under construction has been falling since May of last year.

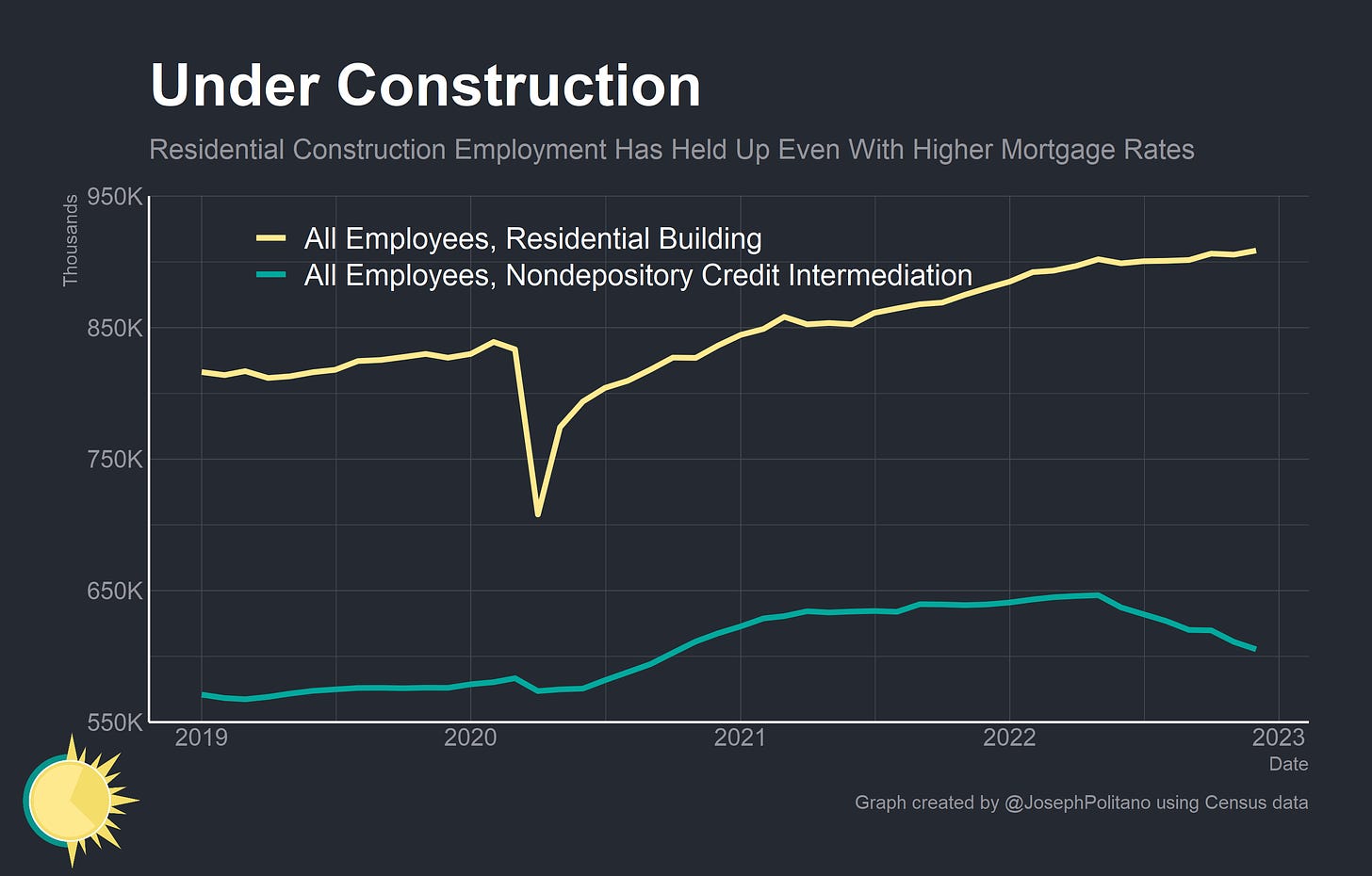

Critically, the massive amount of units under construction is also protecting employment in the housing sector. When housing starts began to plunge in 2006, units under construction and employment in residential construction rapidly followed suit. Today, the massive drop in new housing starts hasn’t yet led to a fall in residential construction employment, only a stagnation in employment growth. In fact, overall US construction sector employment is at a record high right now and wage growth in the industry has been robust—although the rise in mortgage rates is hurting other sectors of the labor market (like nondepository credit intermediation, which includes mortgage lending).

This is what makes today’s housing market—and its relationship to inflation and cyclical economic conditions—so unique. Housing and housing employment are supposed to be one of the most interest-rate sensitive sectors, but so far they’ve shown remarkable resilience to a historically rapid rise in interest rates thanks to latent demand and construction backlogs. Raising interest rates usually initially presents a supply shock to housing by rapidly cutting off new completions—something that exacerbates short-term housing inflation—but so far the number of completed new units coming onto the market has remained largely unaffected. That’s the ideal scenario for a “soft landing” in the housing market—higher rates leading to a slowdown without badly damaging employment or housing supply—but the big question is for how long this can hold with mortgage rates still elevated.

The path for housing prices will play a key part in whether the sector can stick the soft landing—the Case-Shiller National Home Price Index just took a dip for the first time in years, and it’s likely broader measures of housing prices will follow suit. However, realtor.com shows median listing prices per square foot up nearly 9% from last year’s levels—a symbol of how much work historically large rent increases and overall inflation have done to offset the rise in mortgage rates. Given how much of aggregate US wealth is held in real estate, how much borrowing is done against housing, and how the effect of wealth changes/capital appreciation on consumption is stronger for real estate than other asset classes, home prices play an outsized role in American consumer demand—and therefore carry outsized importance for the broader macroeconomic outlook.

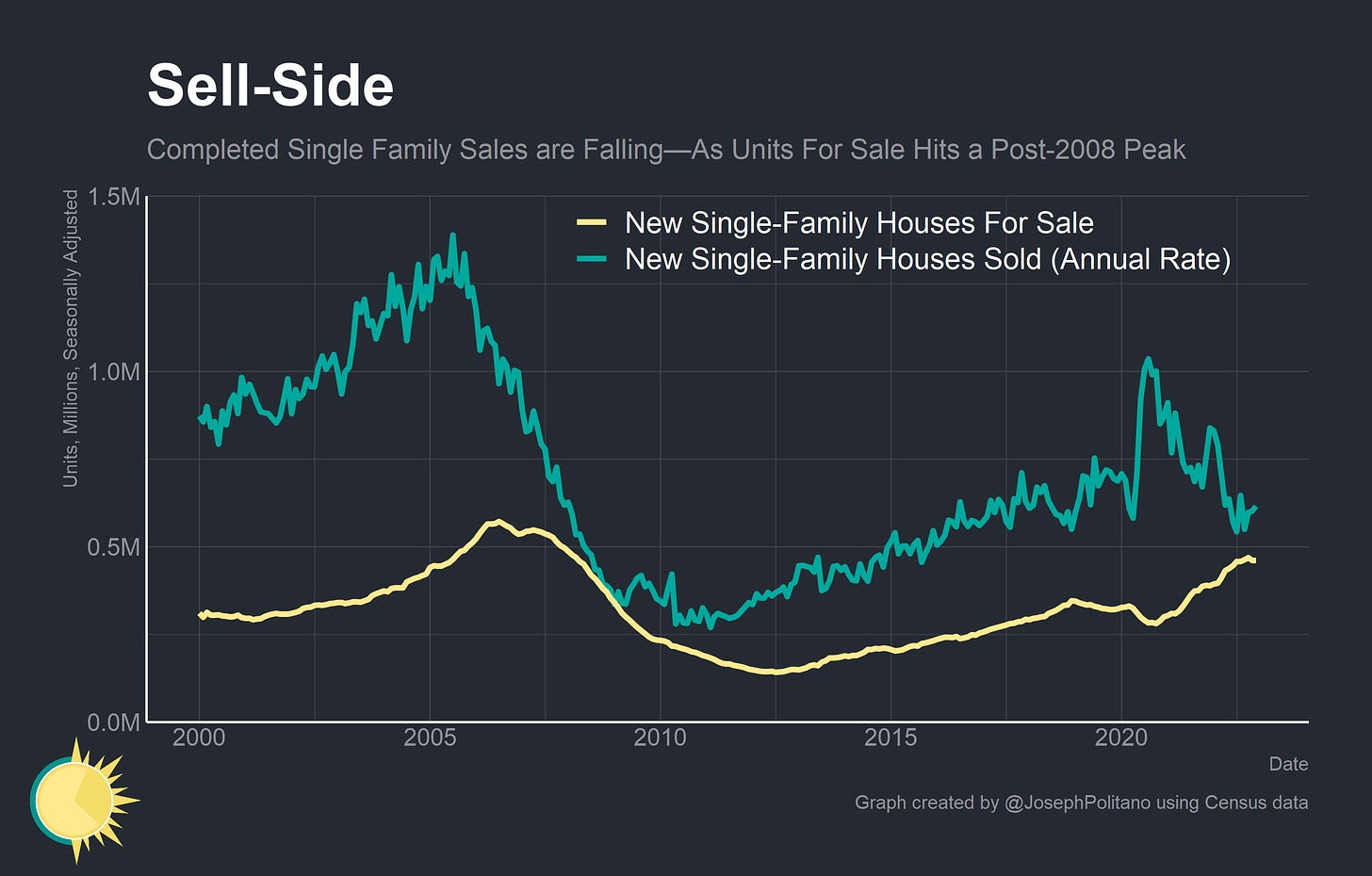

And prices could shift more quickly than normal because the homebuying market remains anything but stable. New home sales have dipped below the pre-pandemic average even as the number of houses for sale has surged—pushing the relative amount of new inventory on the market to post-2008 record highs. But overall and active listing counts remain well below pre-pandemic norms even though they are quickly rising. It’s a recipe for uncertainty at the very least—a thinner market is one that’s much harder to make sense of in the moment.

Conclusions

Still, the defining characteristic of the post-2008 US housing market has been a persistent nationwide shortage. For both renters and homeowners, the share of vacant units is at or near a historic low, indicating just how tight the housing market still is. Overall rent levels are at historic highs—even though rental inflation is slowing alongside declines in household formation, wage, and job growth.

In that way, the housing market feels more like a passenger than a driver—instead of movements in the housing market pushing the labor market, it’s movements in the labor market that look to dominate the housing market. Whether housing stabilizes may, like so many other things, come down to whether the labor market can stabilize.

Love the level of detail, research and scrutiny that Joseph applies to a very complicated subject with so many influences. Really fascinating and Thanks Mr. Politano!

Wondering how much tech layoffs (particularly of H1B visa holders) will have an impact, including from H1B immigrants coming to the US and buying the higher end of the market.