Canada's Balancing Act

Despite Being Hit Harder By the Pandemic, Canada's Economy Enters 2023 on Comparatively Strong Footing

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 22,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Canada’s economic fortunes are necessarily tied to America’s, with the two nations sharing one of the largest bilateral trade and investment relationships in the world and maintaining near-synchronous business cycles. But that doesn’t mean Canada always follows in America’s footsteps—at the onset of the pandemic, Canada’s increased economic exposure to commodity exports, international migration, and tourism left it acutely vulnerable. As a fiscal surge and credit expansion fueled a rapid recovery down south, Canada’s more conservative approach made it look like their economy was falling behind—Canadian real GDP growth lagged significantly behind American growth throughout 2020 and 2021.

But now, it’s the Canadian economy that looks to be on better footing than its American counterpart. Better public health policies meant that COVID-19 did much less damage to Canadians. Employment rates—already higher up north—recovered faster and have surged to new record highs. Output growth rose, fueled by a commodity boom and rebounding in-person spending. Immigration and tourism finally returned—with Canada letting in a record number of permanent residents for the second straight year in 2022.

All of that arguably comes with less pain on the inflation outlook—although the commodity boom has pushed nominal growth up, Canadian firms report less-binding capacity constraints across a variety of metrics and expect cost pressures to decelerate significantly over the next year. At their most recent meeting, the Bank of Canada raised rates by 0.25% and said that “if economic developments evolve broadly in line with the [Bank’s] outlook, Governing Council expects to hold the policy rate at its current level while it assesses the impact of the cumulative interest rate increases.” In other words, a pause if not a pivot—in direct contrast to the “ongoing increases” in interest rates that American central bankers feel are necessary to contain inflation.

Still, yesterday’s extremely strong jobs data from the Canadian Labor Force Survey—which showed employment rising a full 0.8% in one month—will most likely convince the Bank of Canada that the economy can handle higher rates. But extremely strong job growth coupled with decelerating wage pressures (which are already more subdued in Canada) should make a soft landing more, not less, likely. In other words, Canada’s balancing act might just pay off.

Inflation

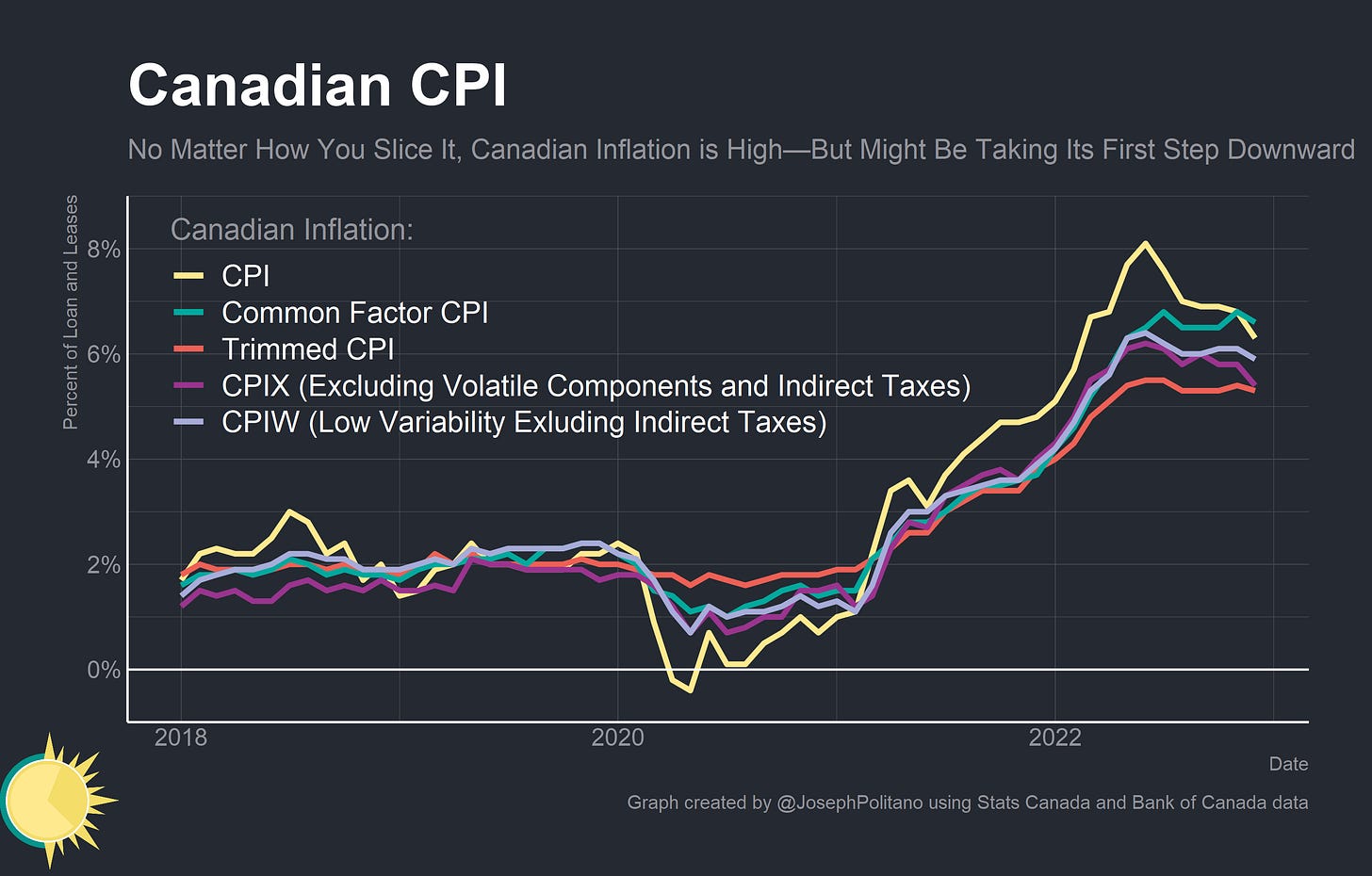

Inflation in Canada—as in most of the world—has surged over the last two years as loose monetary policy mixed with ongoing supply shocks and a surge in spending across the board. No matter which way you slice it, Canadian inflation is far above target—even trimmed CPI and CPI excluding volatile components and indirect taxes have grown more than 5% over the last year. Still, the most recent data has shown a marked deceleration in core inflation—which is part of the reason the Bank of Canada wanted to take a wait-and-see approach.

Canadian firms are also convinced that inflationary pressures are abating—large majorities, on balance, expect input and output prices to decelerate even as wage growth speeds up. That’s the exact opposite of what would be expected under a theoretical worst-case scenario wage-price spiral—and would be a boon to Canadian workers, who could see substantial real wage increases.

Canadian businesses likewise see capacity constraints as abating, albeit slowly and unevenly—more than three quarters said they would have “some” or “significant” difficulty in meeting an unexpected surge in demand at the start of 2022, an all-time high. Those pressures are, perhaps unsurprisingly, strongest in the manufacturing sector—plagued by supply chain issues—and in the commercial, professional, and business services sector, which likely reflects wage pressures on restaurants and other low-paying service industries.

Still, those bottlenecks seem to be rapidly easing. When taking a much broader view, the frequency of supply-chain and labor bottlenecks both hit record levels in mid-2022 but moved down quickly in the fourth quarter of this year. That’s partly thanks to a rapid slowdown in industry and manufacturing—especially the kind of export-oriented commodity-related sectors that Canada specializes in—but also reflects tighter monetary policy cooling the economy.

But looking at the more narrow data that actually goes back before the Great Recession, it becomes clear that today’s Canadian labor shortages aren’t uniquely bad. In fact, the number of companies curtailing production due to a lack of workers is in-line with Canada’s much stronger economic growth periods in the early 2000s—it’s really only against the backdrop of the weak post-Great Recession period that today’s labor market looks tight.

The Canadian Labo(u)r Market

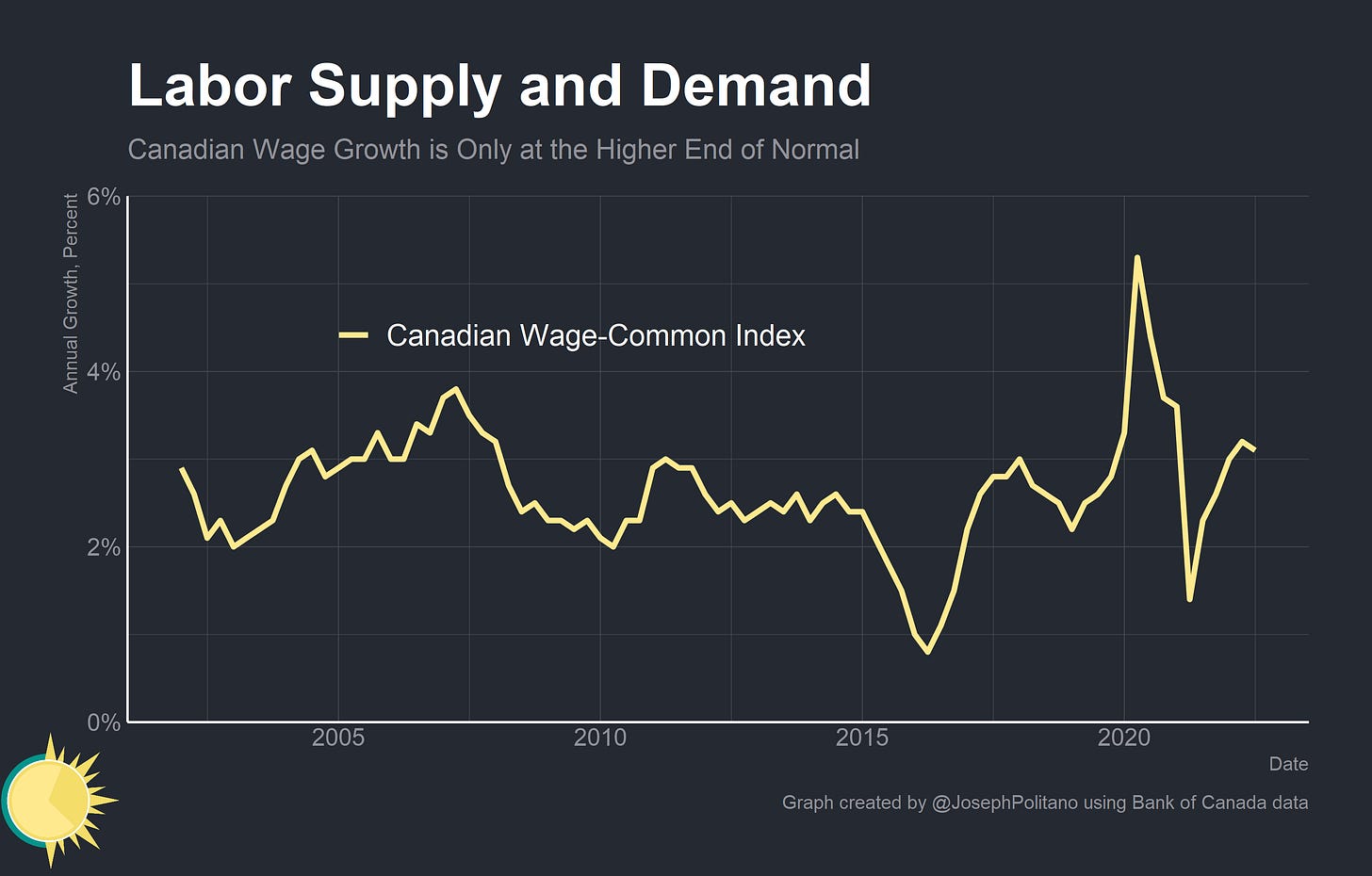

Plus, aggregate Canadian wage growth remains comparatively muted. The Bank of Canada's wage common index, which attempts to wrangle the disparate measures of Canadian wage growth into one underlying measure, shows wage growth remaining only just above 2010 highs and broadly in line with normal growth patterns.

Canadian job growth has also been strong and broad-based, with professional, educational, and health services leading the way. Only lower wage sectors most exposed to the pandemic, especially retail trade and food services, have bled jobs on net.

Canadian growth has also gotten a major boost from the return of international immigration—in fact, Canada posts the fastest population growth in the G7 thanks to its immigration policies. After stalling from 2019-2022, the number of recently arrived prime-age immigrants, employed or otherwise, hit new record highs in 2022.

Canada's broadly better handling of the pandemic has also helped smooth out its labor market. The wave of retirements America saw thanks to COVID was much more muted in Canada, as were interruptions from illness, childcare, or family care. Basically one year into the pandemic all of the major labor supply shocks from COVID had been contained, and the large rise in labor force exits recently has mostly been about a return to school and higher education.

In total, it’s remarkable how balanced the Canadian labor market looks. Among G7 members, it has had the strongest employment recovery, with employment levels now surpassing the UK and closing in on Germany despite having massive job losses at the start of COVID. That employment recovery has been solid across the board, with significant gains for visible minorities, women, and non-college-educated workers. Plus the surge in employment has not come alongside unprecedented reports of production impediments from labor shortages in the way it has throughout much of the US and Europe.

Canada’s Commodity Cycle

Still, there are some cyclical headwinds still facing the Canadian economy. For one, the price of Canadian oil, gas, and other commodities has slipped significantly from their 2022 highs. The Bank of Canada's commodity price index, which looks at a weighted average of prices for major Canadian commodity exports, has fallen more than 25%. For Canada, the supply shock to food and energy prices from Russia's invasion of Ukraine was partially offset by the surge in value for Canadian commodity exports. As those prices unwind, the positive effects of global supply improvements will be partially offset by falls in revenues for Canadian miners, drillers, and farmers.

That can most clearly be seen in Canada's goods trade balance—especially with the United States. As the value of Canadian commodity exports to the US soared, the trade surplus with America hit record highs and was more than enough to offset a significant rise in Canadian imports from the rest of the world. As prices fell, so too did Canada's surplus, and the country is once again notching the trade deficits typical of many high-income nations.

In addition, Canadian homebuilding and residential investment are at risk as rising interest rates impact mortgages and other forms of lending. Like the US, Canada experienced a surge of new housing starts relatively early in the pandemic as people looked to upgrade their accommodations for more homebound lifestyles. Unlike the US, much more of that boom was in multifamily housing—which represents 3/4 of all new Canadian units—and thus far homebuilding has been less affected by rate hikes. But Canada remains more vulnerable to a housing downturn because of the shorter-term nature and higher amount of leverage in their mortgage market.

Conclusions

Canadian banks also don't seem to be tightening as aggressively as their American counterparts—although Canadian businesses do report feeling more credit constrained as rates rise. It fits into a pattern of signs of weakness in the Canadian economy that seems, nevertheless, stronger than their respective indicators in the US.

Still, it’s almost impossible to imagine a total disconnect between the two economies. If the US economy sours, it’s practically inevitable that Canada will too—the Bank of Canada’s main downside risk to its inflation forecast was a severe global downturn that would cause “weaker foreign demand, lower terms of trade, and spillovers into Canada’s financial system”. But over the last three recessions, the median Canadian has fared significantly better than the median American—a small concession, to be sure, but a reason to be optimistic that Canada’s balancing act can work again.

Canada is made up of:

Energy,

Banks,

Real Estate,

Maple Syrup

And

Dividends.

Anytime I want to get a gauge on the country I quickly look there first.