The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Each producer or trader may arrive individually, by weighing his or her own interests, at the precise stocks and reserve capacities that need to be kept, and yet it may still be that all the salable products in the warehouses and all the products available after a slight delay by drawing on reserve capacity together exceed (substantially exceed) the amount the entirety of buyers could possibly buy. Macroeconomists may conclude that aggregate employment matches the natural rate. Yet many people still feel that they are excluded from employment, and society’s performance would be greater if they too were drawn into work.

János Kornai, Dynamism, Rivalry, and the Surplus Economy

Hungarian economist János Kornai is most known for his work on the economics of shortage in the planned economies of the Eastern Bloc. In his view, the soft budget constraints of publicly owned production units and enterprises in planned economies drastically hampers the efficiency of the economic system. When firms are not disciplined by profit-seeking private ownership they become constrained only by the amount of labor and resource inputs they can claim. The result is constant shortages of everything from grain to labor to housing to vehicles to telephones. The macroeconomy is stabilized through forced savings and rationing mechanisms instead of through prices and inventories. Labor productivity, innovation, economic dynamism, and standard of living suffer tremendously. Tight control of the political sphere is required to prevent a suffering citizenry from demanding economic and democratic freedom.

Kornai was proven right by the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. No matter what metric you use, the Soviet system had completely failed to compete with the West. Today, outside of a few tin pot dictatorships, no country implements the kind of extreme centralized planning of the old Soviet Union. Nominally communist countries like China are just capitalist systems—stock markets, landlords, billionaires and all—that retain the human rights abuses and political repression of the Soviet system. Capitalism won and is now standing alone.

In Dynamism, Rivalry, and the Surplus Economy Kornai refocuses the analytical lens he used on communism in Economics of Shortage and The Socialist System, The Political Economy of Communism on the capitalist system. Where the soft budget constraints of planned economies cause firms to hoard factors of production, the hard budget constraints of market economies forces them idle surplus capacity and desperately hawk their wares. Where the firms of the socialist system struggled to diffuse government technical innovations or develop innovations of their own, dynamic firms in capitalist economies are in desperate struggles to invent and deploy new technology. Where the labor markets of the centrally planned economies had slow productivity growth and extremely high employment levels, market economies encourage productivity growth while pushing unemployed workers to the sidelines. In Kornai’s view the capitalist system is one of surplus; surplus inventories, surplus capacity, and surplus workers.

Demand-Constrained Production

I suggest instead that demand-formation is not composed of two still photographs but it is a movie; a continuous interaction between buying intention (which may or may not be well defined at the beginning) and adjustments to the available supply and vice-versa. Instead of two static numbers (notional and actual), we see an adjustment process. In a surplus economy this process does not run against supply constraints very often, but, even when it does, we witness a certain adjustment of demand to supply.

János Kornai, Dynamism, Rivalry, and the Surplus Economy

In Kornai’s seminal paper “Resource-Constrained Versus Demand-Constrained Systems” he argued that the Eastern bloc economic system was permanently predisposed to shortage by the constraints on firms. Firms in the socialist system had soft budget constraints, meaning that the state directly or indirectly compensated the firm anytime it incurred financial losses. Enterprises knew this, and so they were incentivized to focus heavily on ceaseless expansion and investment with little regard to productivity. When all firms focus on expansion and none have hard budget constraints, the result is permanent shortages as managers hoard inputs, workers, and other factors of production while productivity suffers and store inventories shrink. The economy and firms within are only constrained by the total amount of resources available to them.

What constrains firms in the capitalist economy? In short, profit and therefore demand. In Kornai’s view, the private owners of firms in capitalist economies have a single minded focus on profit in order to maximize their returns. Investors build new firms or purchase ownership in existing firms based on their beliefs about the enterprise’s returns, and they are willing to fire CEOs, swap out members on the board of directors, cull middle management, or sell the company as parts in pursuit of profit. Instead of being constrained by their available resources, firms are constrained by their profitability. Firms must be able to validate demand for their products in order to remain profitable, so the economic system as a whole is demand-constrained.

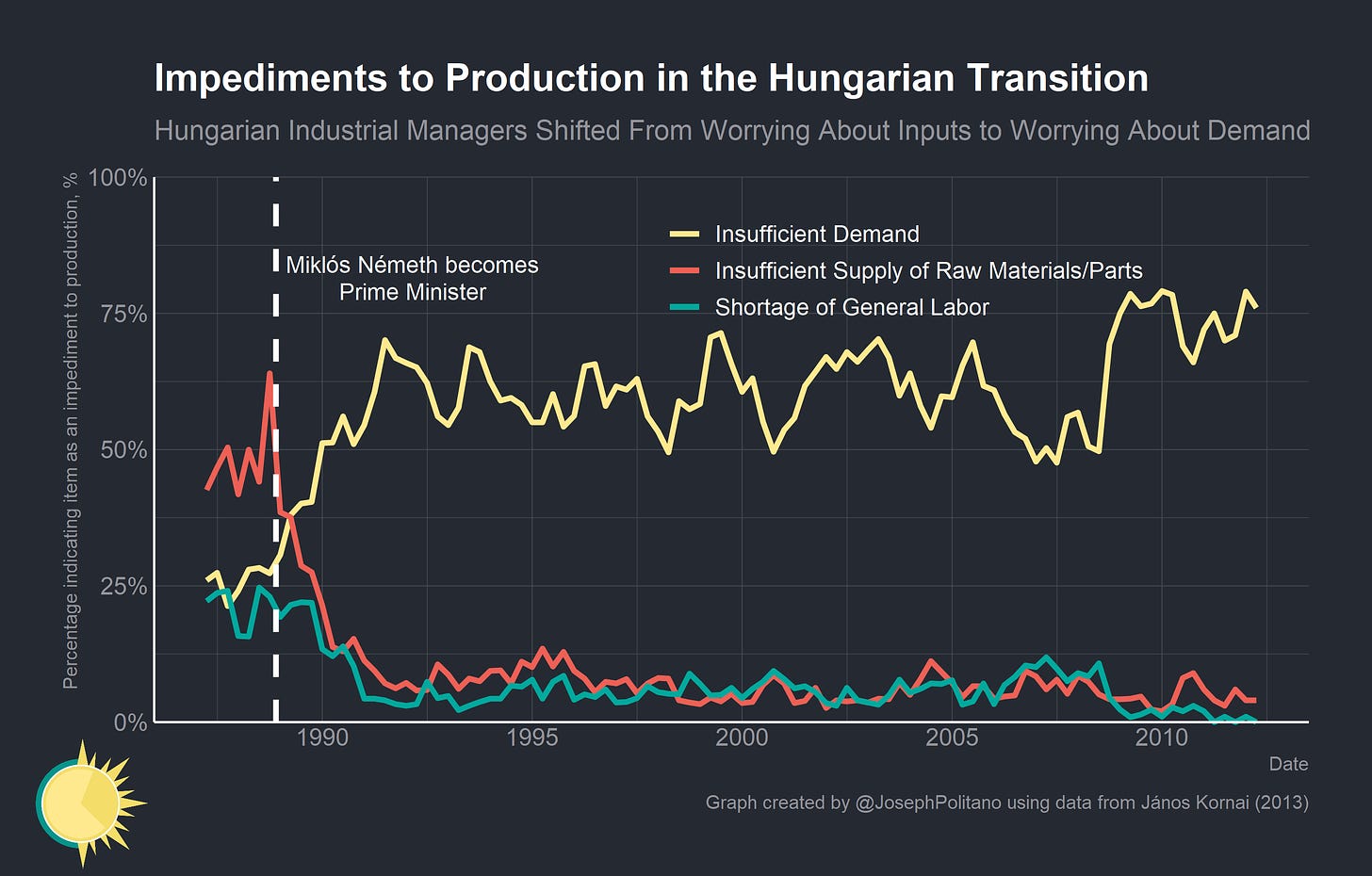

Kornai uses the Hungarian transition from planned to market economy to illustrate the different constraints on production between systems. Under the communist dictatorship, only about a quarter of industrial managers complained about demand shortfalls or labor shortages while almost half complained of insufficient raw materials or other inputs (respondents could select multiple answers, and not all answers were charted here). After Prime Minister Miklós Németh took office and began the country’s shift toward capitalism, firms became much less worried about inputs and labor and much more concerned about demand. Post transition, more than half of managers consistently cited insufficient demand as an impediment to production, compared with less than 15% citing labor or materials shortages.

Rivalry, which in Kornai’s telling is analogous but not quite the same as competition, is also central to the market economy. Kornai views monopolistic competition, where firms sell differentiated products that are imperfect substitutes, and oligopolistic competition, where a small group of firms have the majority of the market share, as the default system of competition in capitalist economies. Firms utilize economies of scale to increase efficiency and strengthen their bargaining position against workers, while rivalry forces them to compete on price and non-price levels while preventing them from becoming inefficient monopolists.

However, the most important part in Kornai’s story is how rivalry pushes firms to innovate. Searching for new markets to lay claim to and devising ways to outflank their competitors, firms more often engage in innovation seeking coupled with investment and expansion rather than attempting to compete solely on prices or quality. While the gas stations of the world may be stuck competing with each other only on prices, the story is completely different for firms on the technological frontier. Apple’s products are not the cheapest, but the company remains fabulously profitable because they were first to lay claim to the consumer smartphone market and because their products are most accessible to the average Joe. Amazon did not become a corporate titan because its books were cheaper, rather because it was a first mover in the e-commerce and logistics revolution brought on by the internet. Besides the innovations on the extensive margins that are most visible, firms are also constantly working to innovate on the intensive margins to increase output productivity. Importantly, an “equilibrium” is never reached where consumers’ demand and firms’ supply are satiated by a single product at a single price and quantity.

The Surplus of Supply

Mainstream economists are ill at ease if excess capacity, inflated stocks, or excess supply appear in a capitalist economy. They see such resources as waste, but I see the surplus economy as one of capitalism’s great virtues, albeit one with several detrimental side effects.

János Kornai, Dynamism, Rivalry, and the Surplus Economy

The interaction between rivalry and demand-constrained production creates the surplus economy, most visible in the surplus capacity and inventories of firms. Firms are unable to accurately predict consumer demand and constantly keep surplus inventories to account for this fact. Firms keep some capacity in reserve in the event that they need to pounce on an opportunity for greater market share or need to respond to a shock that increases consumer demand for their products. The result is fully stocked grocery stores with rotting produce being thrown in the garbage and sprawling industrial parks where some assembly lines are unused.

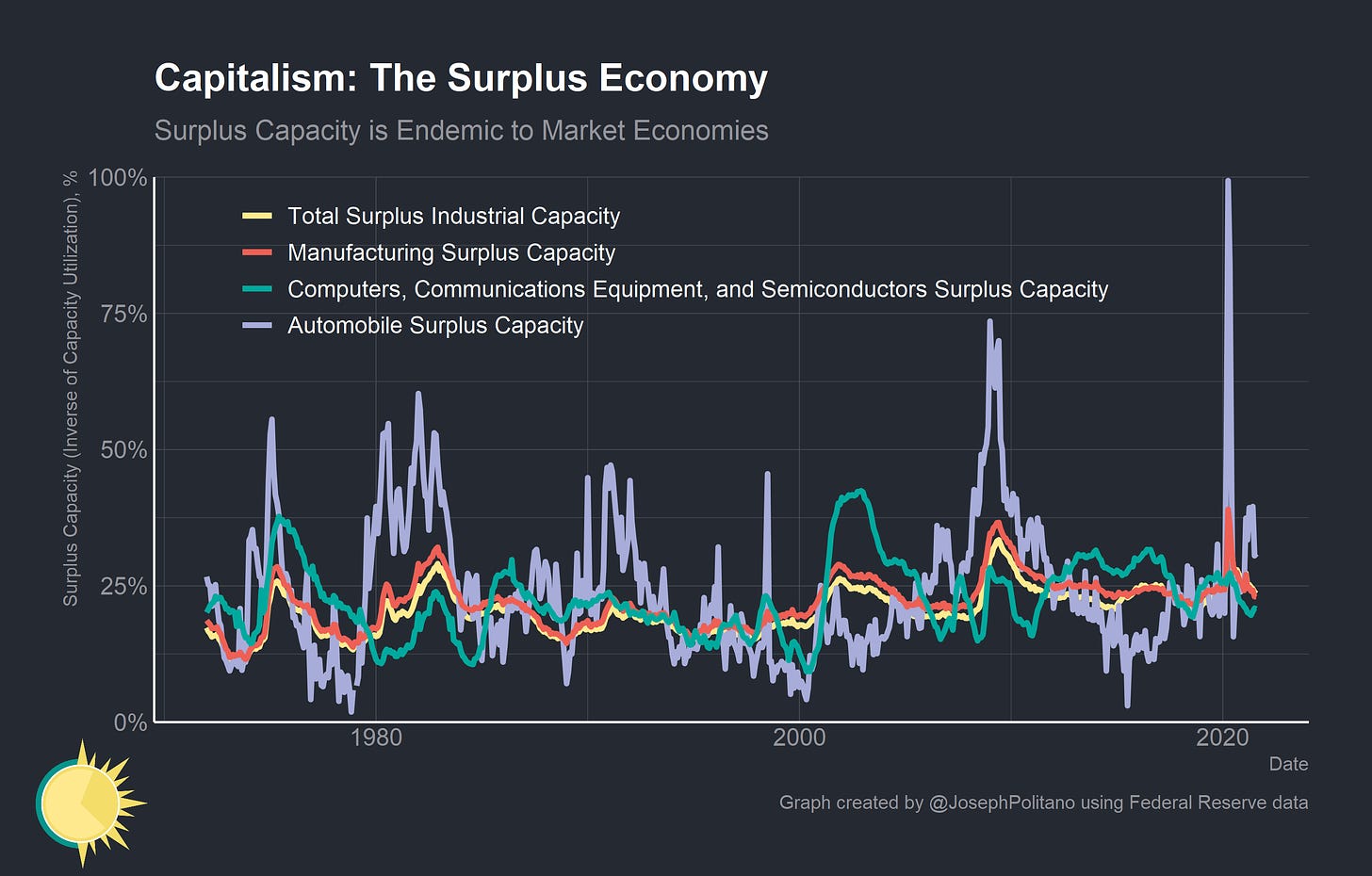

In the chart above, you can see the “surplus capacity” (in this case just the inverse of capacity utilization) for various industries in the United States. At any given point in time, between 10%-30% of all industrial capacity is unused surplus. Only rarely and in specific sectors does surplus capacity approach 0%, and these tend to be periods of high relative demand butting up against rigid supply constraints that require significant long-term investment in order to be alleviated. Surplus capacity does regularly float into the 25-50% range, and in occasional periods of crisis (the kind the automobile industry experienced in 2008 and 2020) the vast majority of capacity can be surplus.

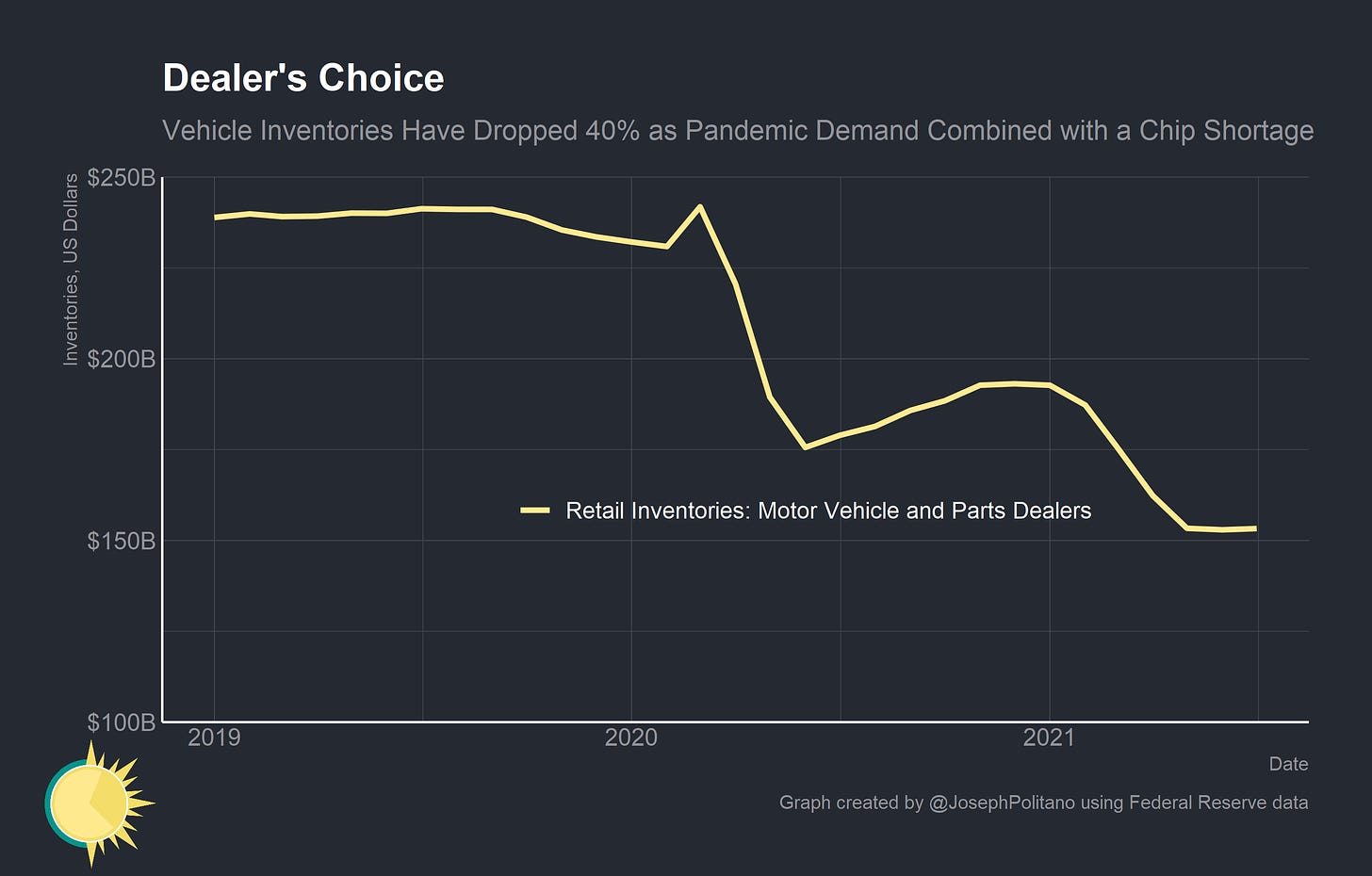

If surplus capacity is necessitated by firms’ drive to capture a larger section of the market, surplus inventories are necessitated by firms being constrained by uncertain and difficult to anticipate consumer demand. According to Kornai, fully stocked warehouses and store shelves are an unavoidable consequence of a system that is reliant on limited and finnicky consumer demand. Firms generally work diligently to prevent a situation where consumers are unable to find the items they want as easily as possible, so Home Depot carries surplus stocks of hundreds of different paint colors. As shown in the graph above, vehicle dealerships had nearly a quarter trillion dollars in inventories at the start of the pandemic partially so that even in the event of a massive shock they would still have products to deliver to consumers. Even though they were forced to lower inventories by demand increases and production stoppages, dealerships have chosen to raise prices rather than fully deplete their inventories.

In many ways firms in a market economy are extremely desperate to move product. They barrage consumers with constant advertisements—in some cases rivaling military budgets in total spending—to ensure consumers are aware of their products and services. They employ small armies of salespeople and store clerks to guide buyers to their products, offer generous credit to prospective buyers, and ruthlessly work to root out any inconvenience that could stop a purchase. In the Soviet economy, firms barely needed to advertise their products. Shortages were so bad that buyers would queue for hours for food and other staples and sit on waitlists for years to have the opportunity to purchase cars or rent city apartments.

Even in America, shortages show up in cases where the market system is impeded by government planning. Since approximately 2015, the production of new housing units has been even more constrained by intensified zoning regulations and other planning restrictions designed to protect homeowners’ property values. Rental vacancy rates, which can be thought of as analogous to “surplus inventory” in the housing market, have been steadily decreasing while housing prices have been steadily increasing. A microcosm of the shortage economy is emerging in the US housing market, to the detriment of US economic growth.

The housing example is also representative of the importance of system wide demand validation and the risks of hysteresis in a demand-constrained system. Essentially, without government monetary and fiscal policy ensuring that consumer incomes grow at their sustainable maximum, firms may experience a sustained demand shortfall that cuts output in the economy. If output shrinks so too will employment, and unemployed workers will cut their demand even further. Hysteresis results when the sustained low aggregate demand leaves permanent self-reinforcing damage on the economy. Firms tend to expand, innovate, and invest most when they are swamped by current and expected future demand. If firms underinvest in expanding capacity and do not hire unemployed workers in anticipation of low growth, they will contribute to permanently depressed aggregate demand and aggregate supply.

The Surplus of Labor

They pretend to pay us, and we pretend to work!

Popular joke among Soviet workers, circa 1970s

If Kornai believed that the surpluses of market economies were clearly net positives in terms of inventory and capacity, it is in the labor market where he is more ambivalent. Firms in the resource-constrained Soviet system had insatiable demand for labor, meaning employment levels were much higher, especially for women. Soviet workers had guaranteed full employment, although it is worth noting that there was nonzero unemployment, workers were legally barred from quitting without authorization until 1956, and aggressive worker discipline measures were employed by the state at all times. In capitalist systems, the economy must instead maintain “surplus capacity” in the form of unemployed workers.

When Estonia broke off from the Soviet Union, declared independence, and began the transition to a market economy, it experienced a permanent surge in unemployment levels. Figures from before the fall of the USSR put unemployment in the Estonian SSR at approximately 0.3%. Though Soviet statistics should be taken with a grain of salt, it is undoubtable that unemployment increased dramatically after the collapse of the USSR and remained permanently elevated above its pretransition level regardless of economic growth.

In Kornai’s view, the labor market under capitalism exhibits similar characteristics as traditional goods markets; that is a generalized surplus of unused capacity. Unemployed workers are the unavoidable consequence of a system where demand constrains firms’ growth. In addition, Kornai is somewhat amenable to Marx’s interpretation of the “reserve army of labor”; he believes that the credible threat of unemployment is used by firms to strengthen their bargaining position and discipline workers. Firms use their position of relative power and monopsony to pay workers less than their marginal product and extract a degree of surplus value from them.

In Kornai’s view, the trade off for this increased unemployment and worker suppression is increased productivity and economic growth. The relentless drive to innovate and the hard budget constraint push firms to employ workers as productively as profitable, leading to markedly higher rates of income, growth, and productivity. There may have been far more unemployed Estonians after the fall of the Soviet Union, but the tradeoff was a faster rate of economic growth and higher incomes for the bulk of people who remained in the labor market. For Kornai, there is no question which system remains superior.

Conclusions

Kornai’s general deconstruction of capitalism and socialism remains correct, but there are important areas where his reductions need some additional nuance and elaboration. First, as much as he centers the demand-constrained nature of capitalism this book seems to gloss over the critical role of government in managing effective demand. If the capitalist system is to function the government must ensure that aggregate demand grows at a stable maximum and that hysteresis never falls upon the economy. Kornai knows this and expresses it in other work, but I feel it falls to the wayside in this account of the market system.

Second, it is worth elaborating on the role of planning within the market system. Kornai acknowledges that in certain sectors—healthcare and education being most prominent—government planning is almost a necessity given their importance and anomalous structure compared to traditional goods markets. Kornai explains well that government innovation diffuses through market economies faster than in command economies, but it is also true that in many ways the introduction of degrees of planning and rationing are necessary compliments to market structures. State owned enterprises may be less efficient that private ones, but there are limited sectors, industries, times, and places where government intervention or production is beneficial.

Third, Kornai is off by degrees on the structure of labor markets under capitalism. While it is true that capitalism does not exhibit the labor shortages of socialism and will always have frictional unemployment, it is worth acknowledging that most of structural unemployment is a policy choice resulting from poor demand management and instability of the business cycle. Humans are not analogous to store inventories, they are independent agents who actively seek out production opportunities.

Fourth, it would be worthwhile to compliment Kornai’s writing with a discussion of distribution’s affect on production. In his view, the outsized returns of successful billionaire entrepreneurs are necessary to induce people to take the extreme risks necessary of founding innovative companies. He admits that governments must balance wealth inequality with economic growth, but it would help his analysis to examine to how production and consumption are directed to hyper luxury consumption by extreme wealth inequality.

Finally, Kornai’s critical point about the incentive structures of capitalism feels lost among his description of its effects. The ability of capitalists to deploy and redeploy resources and order firms in search of profits is central to Kornai’s explanation of the surplus economy, and is arguably even more central in his story than markets’ ability to aggregate dispersed knowledge. Those attempting to reconstruct the surplus economy without private ownership miss that the hard budget constraint by definition cannot be synthesized and is a system level effect as much as a firm level effect. Having, say, state-run sovereign wealth funds trading in capital markets is merely passing the soft budget constraint from firms to funds without retaining the critical discipline measure of private ownership. Regardless of firm level productivity, the economy becomes resource-constrained at the system level and transitions to a shortage economy without a real hard budget constraint.

There is some good news in Kornai’s work for those fighting for a more equitable world. As long as the hard budget constraint is maintained, the benefits of the surplus economy will remain. Universal basic income, generous unemployment benefits, sectoral labor unions, robust welfare programs, economic regulations, and wealth redistribution are mere differences of degree but not of kind. Running the economy hot does not impinge the fundamental structure and benefits of capitalism but it helps improve broad economic growth and strengthen workers’ bargaining position. In many ways, acknowledging the structure of the surplus economy improves our understanding of the realities of capitalism and allows policymakers to better maximize its upsides and ameliorate its downsides.

If you like what you read, consider subscribing to get free economics news and analysis delivered to your inbox every Saturday!

Something is worth emphasizing here, I think:

"In Kornai’s view, the trade off for this increased unemployment and worker suppression is increased productivity and economic growth."

I don't think this is a tradeoff at all. Rather, worker suppression and especially increased unemployment is a hindrance to productivity and growth. You mentioned the need to keep demand high, but beyond that, the pressure for firms to innovate is higher with full employment.

PS: typo here, looks like you added a word on accident: "consumption by extreme wealth inequality. Inequality"

I'm confused why you cite "The Red and the Black" as an example of not understanding the hard budget constraint. I read this Kornai piece just to make sure I was understanding the concept:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/40728773

Some choice quotes follow.

On almost-hard budget constraints: "The creditor (bank, etc.) grants credit to a firm only if it is creditworthy... If the firm has taken a loan, it must always fulfill every obligation in the credit agreement"

This would seem to still apply if socially-owned banks are providing the loans, or a SWF is owning the stock. Interest and dividends must still be paid, or else the firm will get less financing, and therefore grow slower and risk failure. The "critical discipline measure" is therefore maintained.

On soft budget constraints: "uncertainty is also caused by the continuous redistribution of the financial receipts of firms. The firm cannot foresee exactly how much the state will take away from it, or how much it will give. "

It seems this applies more to bailouts than anything. If a firm knows how much of their stock is owned by a SWF, or how much they are borrowing from a bank, this uncertainty doesn't apply.

"Nor is it crucial by what formula profit shares are distributed among workers... In the case of a hard budget constraint, the managing director would not be indifferent to profit even if his personal share were zero in the short run - since he has identified himself with the survival and expansion of the firm"

Surely, factors that soften the budget constraint will persist under socialism. But as Kornai points out, plenty of these factors are already present under capitalism. So through what mechanism does a SWF, or the system outlined in "The Red and the Black", soften the budget constraint?