China's Imbalanced Economy

The Domestic Economy is Faltering as Exports Hit Record Highs, Leaving China's Economy More Imbalanced than Ever

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 19,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

In broad, oversimplified terms, China’s growth model has relied primarily on net exports of manufactured goods combined with large investments in infrastructure and fixed assets. Export-oriented growth allowed China to profit from access to larger markets in high-income countries and helped provide a steady source of funds for the country’s growing industrial base. Capital controls and direct spending from the government kept investment in housing, infrastructure, and other fixed assets extremely high. The end result has been extremely successful economically—China has steadily moved up manufacturing value chains while building tremendous amounts of domestic infrastructure, reducing poverty, and sustaining extremely high levels of GDP growth.

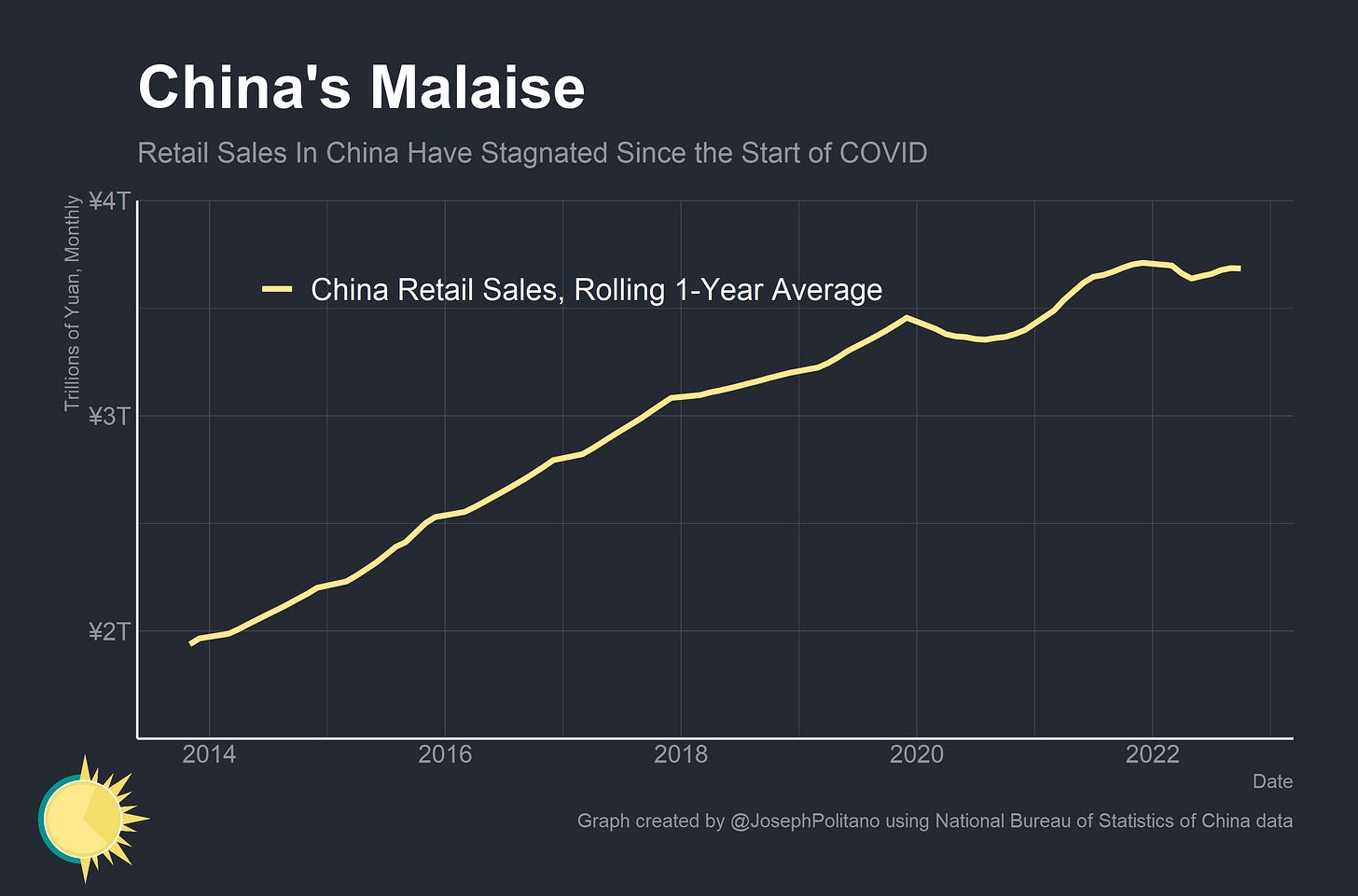

The downside, however, is that the model required household consumption in China to be squeezed. Spending was constrained in order to scrape together the savings necessary for large investments, the value of the Renminbi was kept low to ensure export competitiveness, and wages were suppressed to keep labor costs competitive. Final consumption expenditures therefore make up slightly more than half of Chinese GDP, compared to a whopping 80% in countries like the United States or the United Kingdom.

The main problem with the export-oriented growth strategy is that eventually, you run out of other people’s domestic markets—growth has to eventually shift from an export-driven model with lots of dirigisme to a consumption-driven model with stronger wage growth as countries approach the economic frontier. China’s leaders anticipated this and began talking up “dual circulation” before the pandemic—the country was signaling that domestic consumption would take equal priority to exports as China looked to transition into a wealthier country.

Old habits die hard, however. Since the pandemic, lockdowns and limited support for households have crimped growth in domestic demand. An attempted deleveraging has damaged the country’s property sector as real estate investment falls off dramatically. Net exports—supercharged by global goods inflation, a rising imbalance between domestic and foreign demand, and efforts to preserve export-oriented industrial output amidst COVID restrictions—are once again taking up the mantle and holding up the Chinese economy.

The Big Squeeze

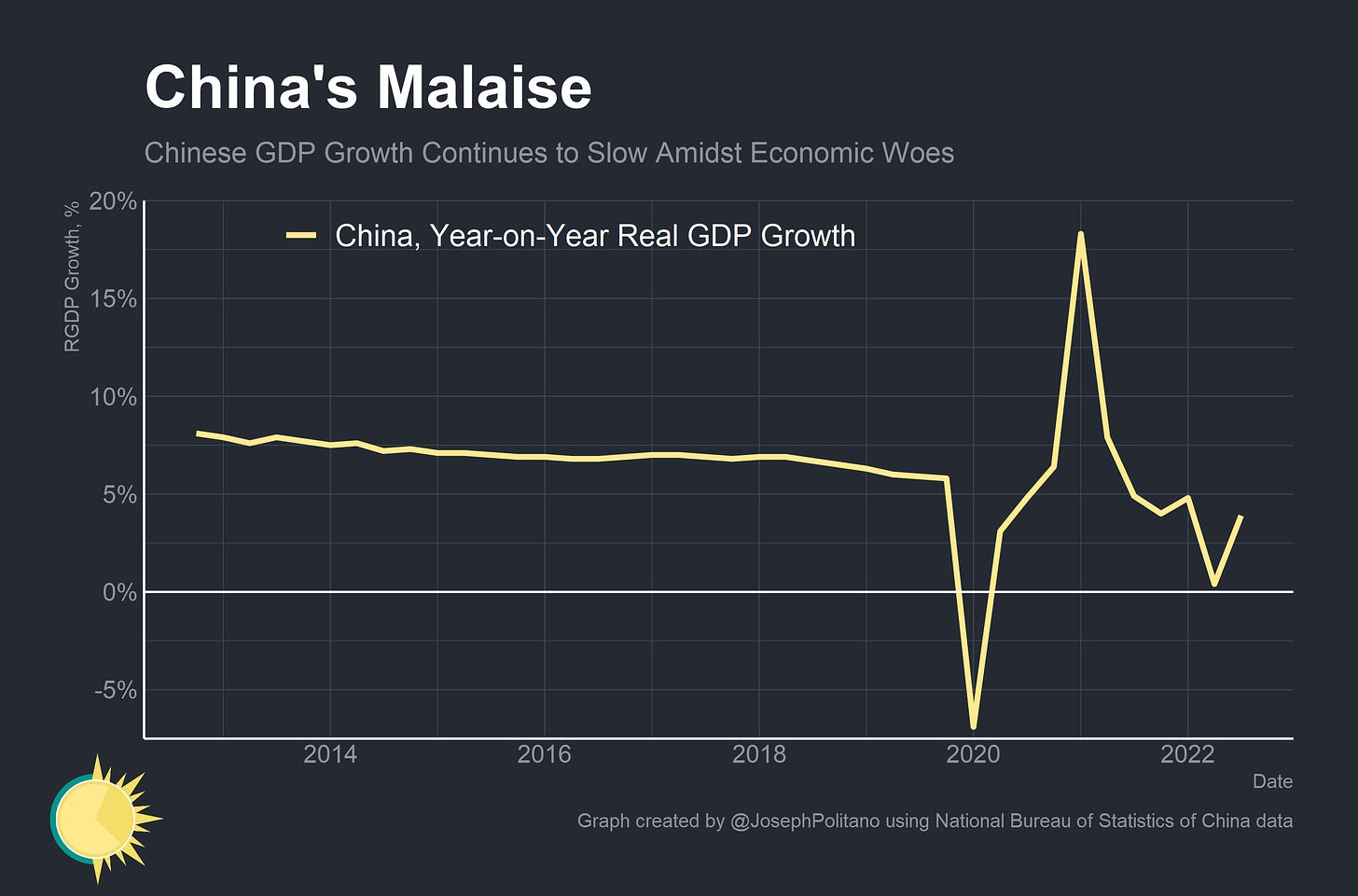

China’s real GDP growth has been slowly declining for years amidst demographic weakness and diminishing returns as the economy matures—but the pandemic put a significant dent in output. Although harsh lockdowns put China in a comparatively better spot than most nations in 2020 and 2021 by limiting case counts, the failures to adopt successful mRNA COVID vaccines or to sufficiently distribute the vaccines China did adopt have left the country in a comparatively much more fragile economic position today.

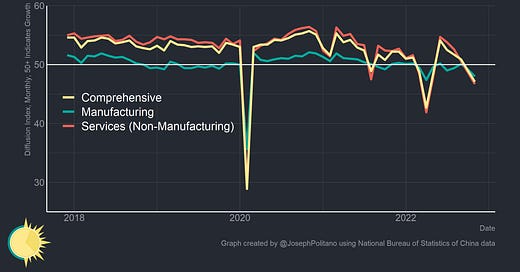

In addition, higher frequency data from surveys of purchasing managers show both the service and manufacturing sectors re-entering contraction in recent months as COVID lockdowns intensified. The significant increase in business volatility during the pandemic is notable—as is the persistent weakness in the service industry as the sector is wrought by rolling bouts of government restrictions and pandemic fears.

Indeed, the Chinese government’s index of real service-sector production also shows contraction this year and intense volatility throughout the pandemic. Although output in October was above pre-pandemic levels, it remains about 10% below the pre-COVID trend and functionally unchanged from last year.

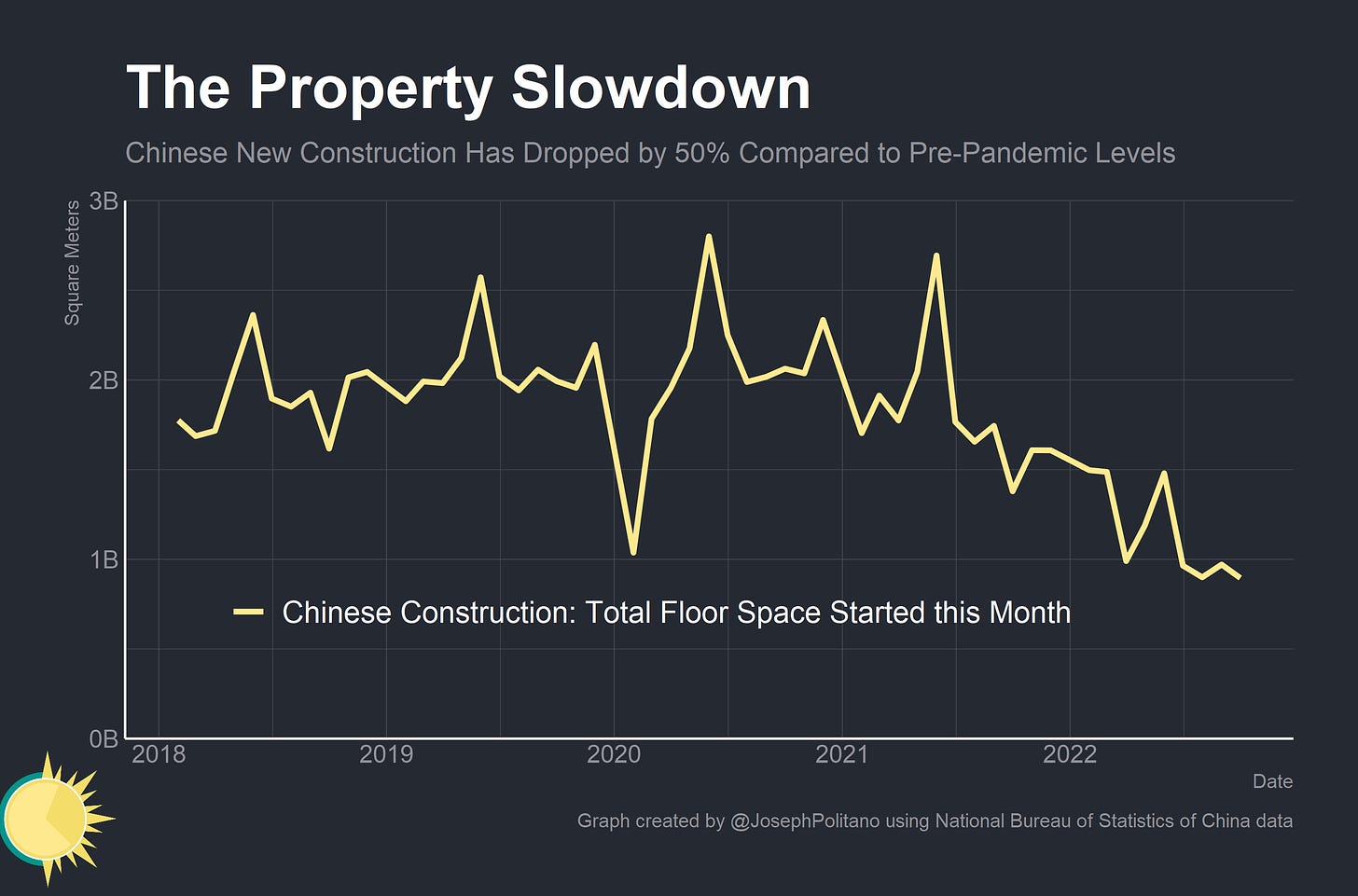

Of course, the other major story of China’s slowdown is the property sector, which has taken major hits during the pandemic. Housing is a double-edged sword for Chinese policymakers—it is one of few areas where households are encouraged to direct their savings and a massive part of domestic infrastructure investment, but its structural importance also confers ongoing worries about systemic financial and economic risks in the sector. A campaign against excessive leverage in the housing industry alongside a general slowdown in the economy threw massive property developer Evergrande and several smaller companies into default late last year, and the sector has been hurting ever since. Chinese property prices fell month-on-month for the first time since 2015 in October, overall construction starts are down 50% from pre-COVID levels, and land sales so far this year are 60% below 2019 levels. Combined with the strictness of lockdowns, the construction slowdown has helped significantly increase Chinese youth unemployment.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.