Did the Energy Crisis Accelerate The Energy Transition?

Maybe—But it Also Forced Nations to Use More of Some of the Dirtiest Fossil Fuels and Harmed the Kind of International Cooperation Necessary to Fight Climate Change

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 27,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

The kind of modern, industrialized society capable of supporting decent standards of living requires large amounts of energy consumption—and the world still uses the burning of fossil fuels to meet the vast, vast majority of those energy needs. This dependency has been put into stark relief over the last few years as a series of rolling energy crises buffeted the world economy—a surge in oil and gasoline prices in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, power shortages forcing blackouts across China, natural gas shortages across Western Europe, and a massive surge in global energy prices that has only recently reversed. It’s more clear than ever that today’s global economy is still extremely dependent on fossil fuels.

This is a problem because industrial-scale burning of fossil fuels has disastrous impacts on Earth’s climate—the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change expects that in a “middle of the road” scenario, carbon and other emissions from human activity will raise global temperatures 2.7°C (4.9°F) above preindustrial levels by 2100. A destabilization of the climate of that magnitude will cause significant harm to global human welfare—displacing tens or hundreds of millions of people, worsening adverse weather events, and reducing global habitability—while also costing global economies trillions via damage to agricultural resources, individual health, physical infrastructure, biodiversity, and much more.

The gap between societies’ stated commitments to decarbonization and the amount of money mobilized towards low-carbon energy investment is yawning—a combination of trillions in new clean energy infrastructure, significant efficiency gains, and cutbacks on polluting activities would be needed to meet stated net-zero-emissions climate targets. Yet during the energy crisis of the last few years, global shortages of fossil fuels forced users to cut back on consumption, incentivized broad efficiency gains, and caused global governments to respond by marshaling large amounts of investment in new energy sources. At the same time, however, many countries turned inward and intensified their reliance on coal and some of the least-carbon-efficient primary energy sources in order to weather the crisis. So did the energy crisis accelerate the energy transition—or did it set us back?

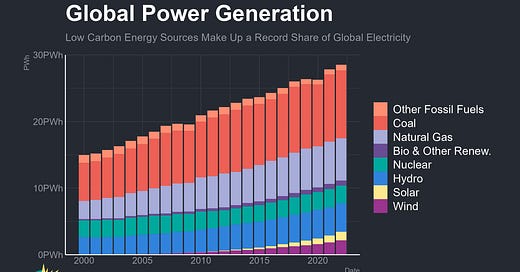

Past and Future Energy

Broadly speaking, there are three main sources for the majority of Earth’s electricity—Coal, the most-common historical and current power producer that also happens to be far and away the worst in terms of carbon emissions, Natural Gas, the growing and now second-most-common source of global electricity that emits significantly less than coal but still has a substantial carbon footprint, and the low-to-no-carbon sources spanning hydro, nuclear, solar, wind, and other renewables. Long-run growth has buoyed electricity production across nearly all sectors, but since the turn of the millennium it has been coal, then natural gas, then solar & wind that have grown the most.

The energy crisis of the last two years, however, has been notable for its rapid acceleration of wind & solar energy, power sources that have been growing for years as their generation costs plummet. In 2017 solar and wind combined to produce a meager 6.3% of global electricity, but by 2022 that number was 12%—annual electricity output from wind and solar grew more over the last 5 years than from the technologies’ inception to 2017.

In the US, the growth of wind and solar electricity generation has been enormous—with aggregate solar generation nearly doubling since 2019 alone. That means America’s dominant decarbonization paradigm looks set to change—over the last two decades, it has been cheap natural gas displacing dirtier coal power that has done the most to clean up America’s grid. Now, it looks to be gas that will start losing ground to renewables—indeed, the share of the US power supply coming from natural gas still remains slightly below the record-high set in 2020 even though wind and solar still make up a relatively small share of the US grid.

However, projections for continued growth in American renewable power are extremely rapid—the Energy Information Administration expects total US solar power consumption to increase by 30% in 2023 and then by another 29% in 2024. Wind power grows by a comparatively low 7.9% and then 3.6%, but that would still mean America could get roughly 1/5 of its electricity from wind and solar alone by 2024.

In the US, at least, it seems pretty clear that the mixture of incentives created by higher electricity prices and policy responses to the energy crisis has accelerated the country’s energy transition. Overall US carbon emissions are expected to fall by 3% by 2024 even as energy production, population growth, and economic growth continue. Annual new residential solar installations by US households rose 40% last year, and the passing of the Inflation Reduction Act last year could mean US emissions will be 30-40% below 2005 levels by the end of the decade.

The Shortage Countries

However, America’s experience with the energy shortage has arguably been among the easiest among major economies—the country is a major producer of oil and gas, consumes a comparatively massive amount of energy and therefore had more room for efficiency gains, and became a net energy exporter in recent years. It is not representative of how the crisis unfolded—or what the ensuing reaction was like—across the world. Blocs like the European Union and China—which had comparatively less room to make cutbacks, produce less of their own energy, and were hit much harder by the shortages themselves—experienced the last few years in vastly different ways.

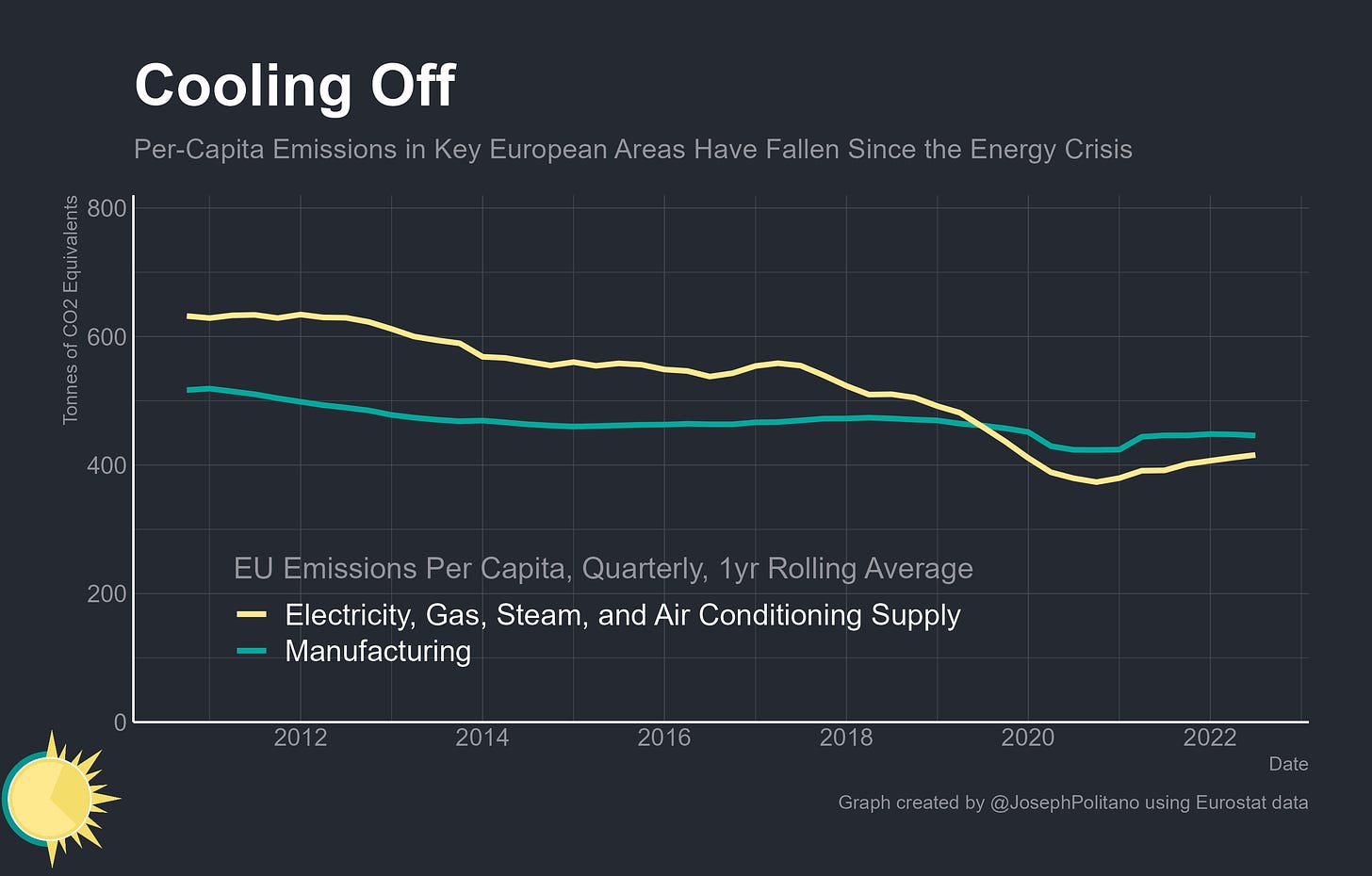

In Europe, emissions from manufacturing and the broader power industry remained well below pre-pandemic levels throughout 2021 and 2022 as the energy crisis wracked the continent. EU Per-capita emissions from electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply have fallen more than 30% over the last decade—but the recent emissions reductions come in large part from unsustainable power cuts rather than switches to low-carbon sources or efficiency gains. In 2021 and 2022, nearly 14% of Finnish households making less than 60% of median incomes reported they could not keep their own homes adequately warm, up from low to mid-single-digit shares before the pandemic.

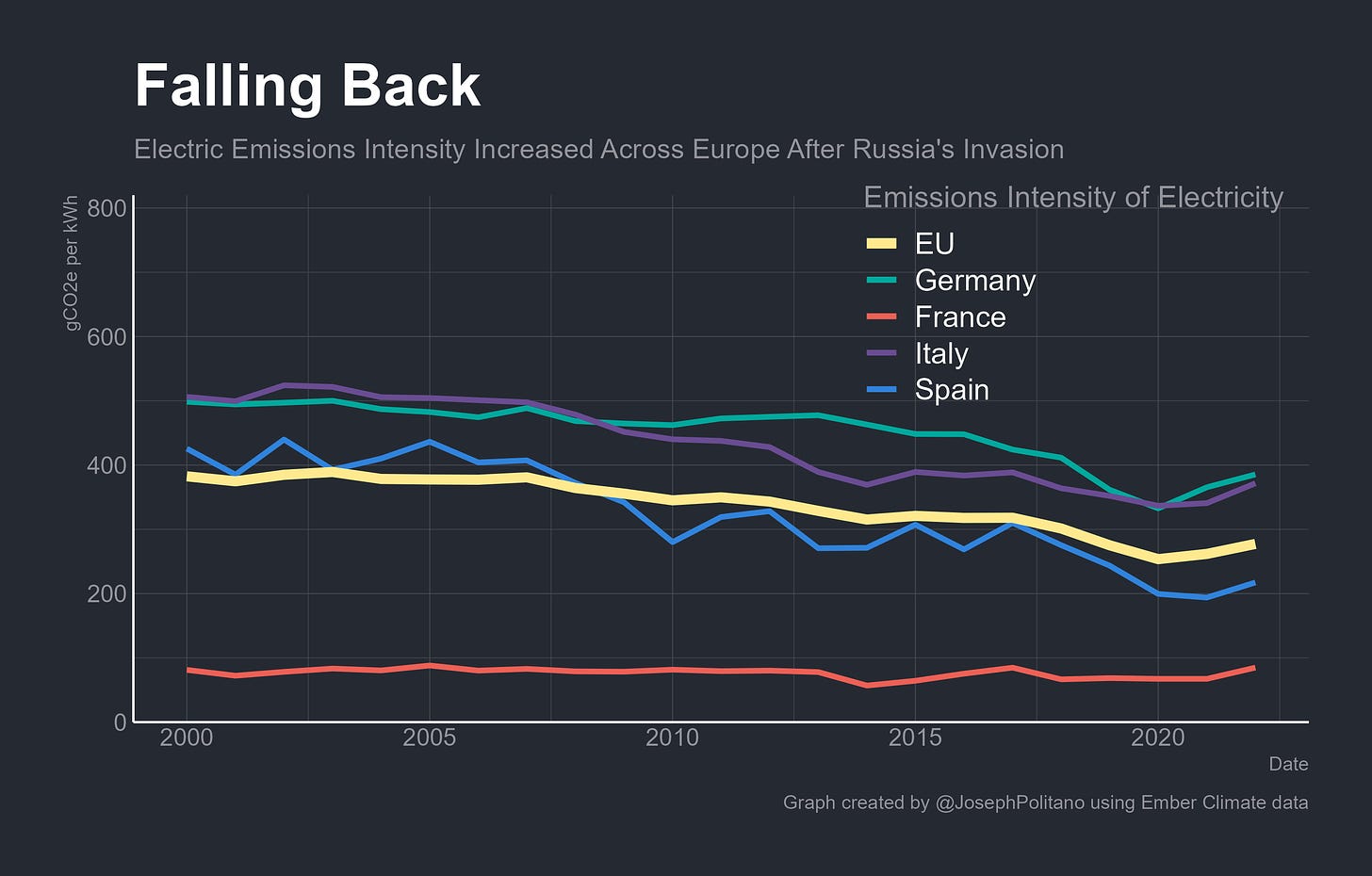

Europeans were also forced to increase their dependence on dirtier power sources—most importantly coal—in the wake of the Russian invasion. EU-wide coal power generation has rebounded from the pandemic-era lows and almost fully recovered to 2019 levels last year. Much of the coal-buying throughout the last few years has been for precautionary storage rather than direct use, and it looks like coal generation throughout the continent will decline again next year, but the increase in EU coal consumption last year was still notable for unwinding years of progress.

Critically, that increase in coal use, combined with supply issues at French nuclear reactors, the shuttering of several German nuclear reactors, and an especially weak year for the EU’s hydropower, has meant that the emissions intensity of electricity across Europe picked up over the last two years despite rapid advances in solar and wind deployment. In other words, the average unit of electricity now produces more carbon in the EU—and the bloc’s power-related carbon emissions reductions since the pandemic chiefly come from a nearly-3% decline in per-capita power consumption.

China’s power grid, plagued by blackouts and brownouts throughout 2021 and 2022, has likewise increased its coal usage substantially over the last few years. China is now the world’s foremost consumer of coal electricity by a wide margin—in fact, since 2019 it alone has consumed half the world’s coal power. Though fossil fuel generation is shrinking share of the nation’s grid, increases in overall power generation mean its outright usage is still rising—the nation’s manufacturing-led economy continues to grow and now consumes 80% more electricity per person than the global average and on aggregate more than 30% of the Earth’s electricity. It’s true that large chunks of China’s emissions represent manufacturing exports that are consumed abroad, but even adjusting for that gives the nation a per-capita CO2 footprint now as large as Europe’s. And the energy crisis led to Chinese industry and policymakers placing much more faith in coal—abundant domestically and easier to store up in the event of a crisis—even as the nation continues investing large sums into renewables.

In both China's and the EU’s case, the result of the energy crisis is likely marginally higher emissions than would otherwise have been expected—short-term solutions to the crisis likely sucked up large chunks of political and investment capital that could have gone towards decarbonization, and the memory of recent events is likely to weigh heavily on policymakers when deciding whether to accelerate the energy transition. The only large positive result could come from the fact that in both cases the blocs are dependent on outside imports to meet a large share of their power needs—being reminded of the downsides to dependence on foreign energy producers could push both countries to accelerate clean energy investments that are less subject to the whims and aims of foreign producers.

Falling Short

Still, it’s important to remember that humanity does not just need to decarbonize the energy grid in order to reduce emissions below catastrophic levels—we also need to increase global power production substantially in order to meet the large amount of electricity needed to decarbonize transportation, manufacturing processes, agricultural production, and many, many more facets of a high standard of living that all take fossil fuels as direct energy inputs. Right now, global consumption of oil and other liquid fuels is still rising despite the energy crisis and the growing popularity of electric vehicles—and even if countries maintain their announced emissions reduction pledges consumption is expected to continue growing through the middle of this decade while remaining high for years.

Plus, global investment in renewable energy isn’t yet nearly enough to decarbonize the grids we have now, let alone build out sufficient capacity to decarbonize the grids we will need for the future. Though at a record high, global fixed investment in renewable energy and related decarbonization projects is only barely half the amount currently invested in fossil fuels projects.

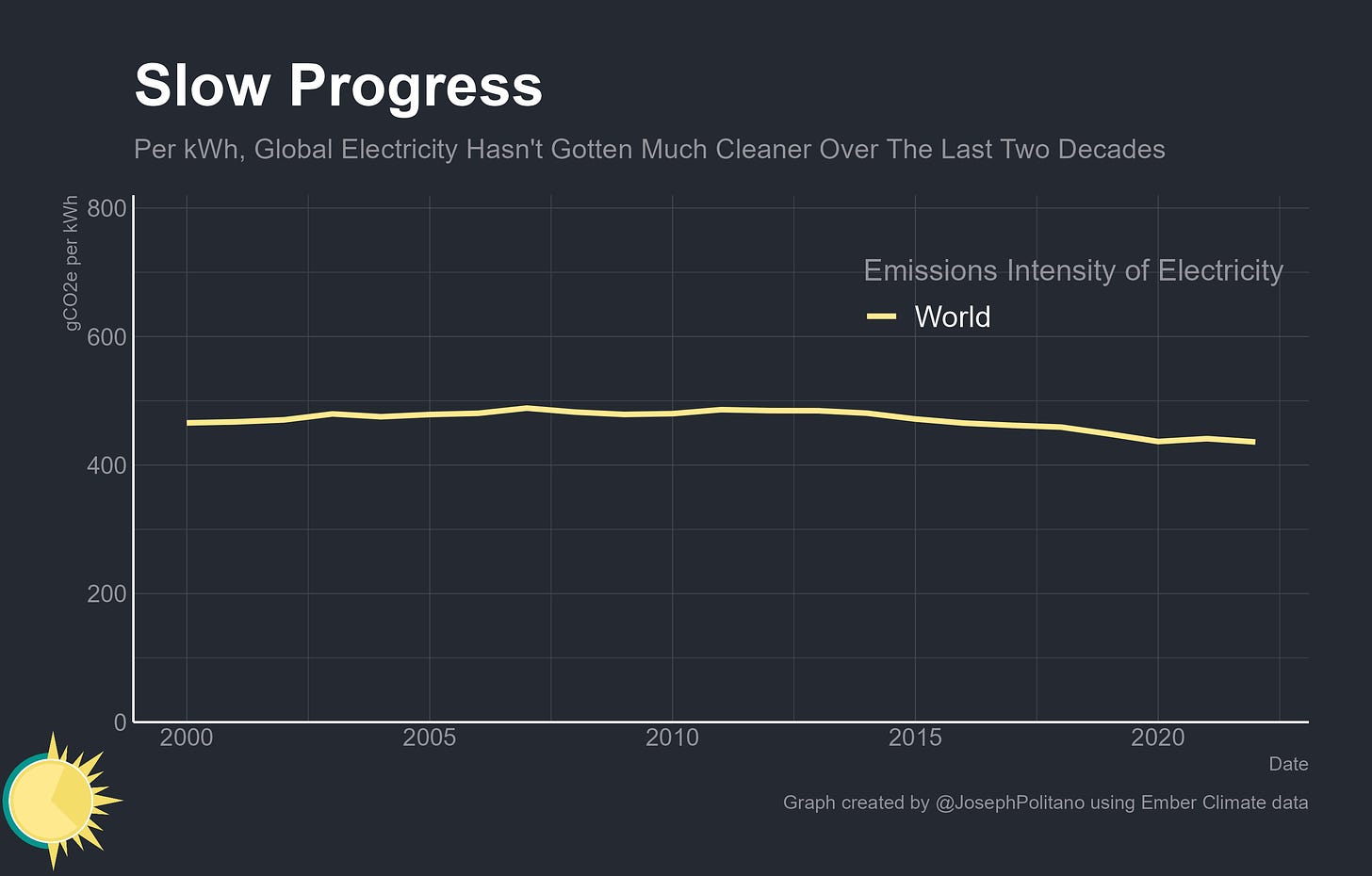

And all the world’s efforts at electrical decarbonization thus far have yielded comparatively little results—globally, the amount emitted per unit of electricity is only down about 6% since the turn of the millennium. Looking at all primary energy—so including transportation energy, household natural gas consumption, industrial processes, etc—average global emissions intensity has only fallen by a mere 16% over the last 56 years. Today’s global economy is still extremely dependent on fossil fuels and their harmful emissions—and it will likely remain so unless significantly more clean energy investments are made.

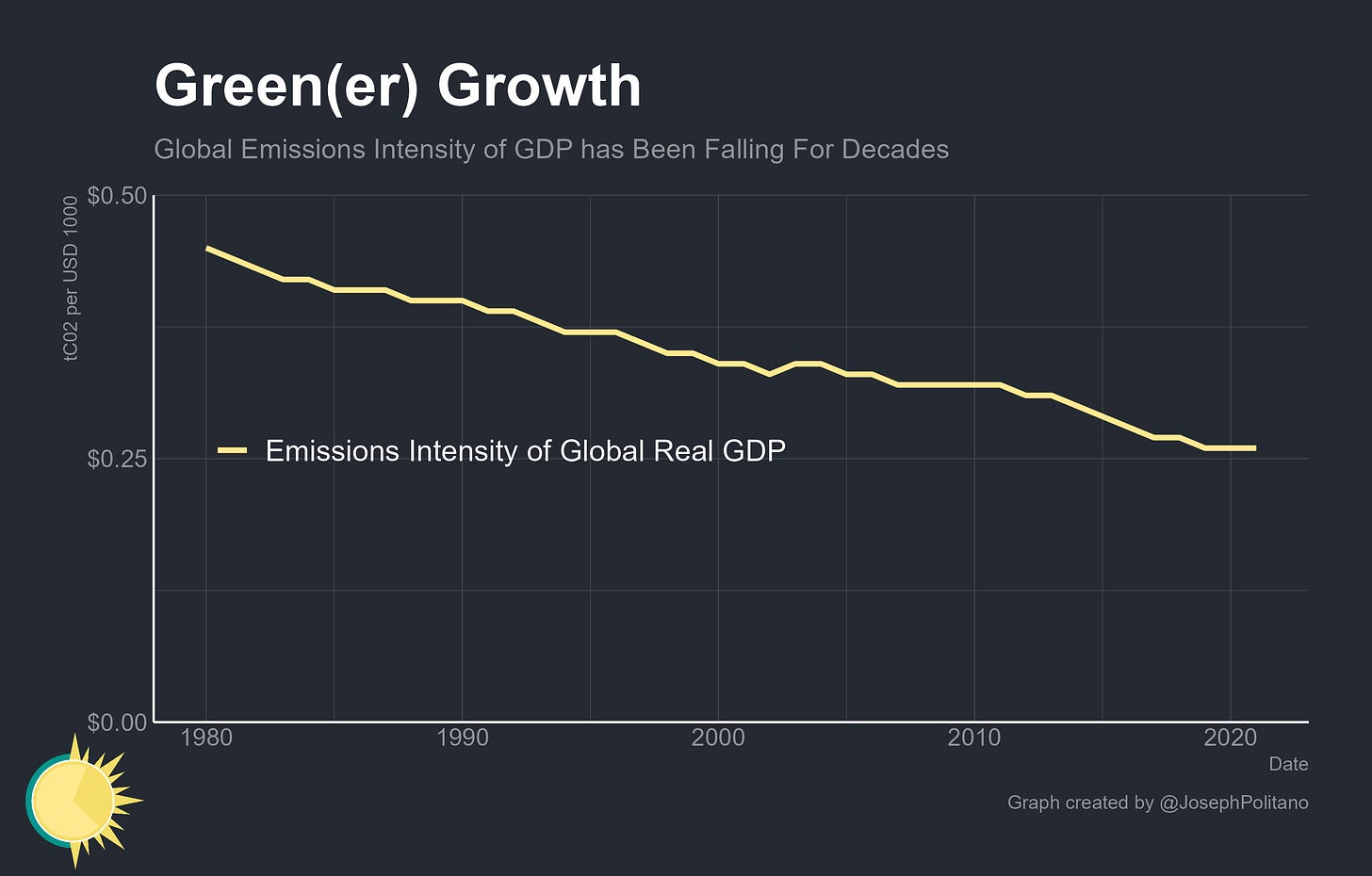

There has, however, been one bright spot over the last two decades—the emissions intensity of global GDP has been declining steadily. In other words, economies produce less carbon per unit of economic output than in prior years, and the decline has been so rapid that for each dollar earned the world economy emits less than half as much carbon as it did in 1950. Our energy itself may not have gotten much more carbon-free, but economies have gotten much, much more efficient at using energy. The end result is that it has never been easier to provide people with good, high-quality standards of living while managing our impacts on the world’s climate as it is today.

That fact may seem like a copout—it’s easy to imagine that output getting more energy efficient as economies get larger would be a fairly consistent reality of growth and technological progress. But that’s simply not the case—from 1820 to the mid-20th century economies got less, not more carbon-efficient as they grew. At the start of the Civil War, Americans emitted about 1/3 of a kg of carbon for every dollar they produced. By 1917 they emitted 1.6kg, five times as much as in 1960, per dollar of output. By 2021 they emitted less than one-seventh as much per dollar of output—only 0.21kg. The British Economy, today, is more than four times as carbon efficient as it was in 1820, meaning despite more than a century of growth it now emits less than it did in 1890. Raising global standards of living while protecting the climate will require economies to get even more carbon efficient going forward.

Not The Last Fossil Fuel Crisis

The energy shortages of the last couple of years will likely not represent the last crisis of the fossil fuel era—the reality is that the twilight of the age of oil, coal, and gas is still years away and that global economies likely won’t do enough to bring its end about quicker. That’s bad because energy crises, despite consistently mobilizing large responses and giving rise to strong efforts to reduce fossil-fuel dependency, undercut the cooperative efforts necessary to manage the energy transition.

Pakistan has faced persistent threats of acute energy shortages over the last two years—the liquefied natural gas it imports for a large chunk of its energy needs has been bid up dramatically thanks to the crisis in Europe, and companies keep canceling deliveries the nation contracted out years ago. Australia, the world’s largest producer of lithium, and China, the world’s largest producer of electric vehicles, have been locked in a yearslong trade war in part fought via the partners’ coal trade. European policymakers have consistently voiced their displeasure with an America they view as profiting from their continent’s energy crisis. In a world where nations feel that energy is a key strategic weakness that could be exploited by geopolitical enemies, they will be much less likely to maintain the kind of global partnerships necessary to protect the climate. For the sake of the energy transition, we ought to be vigilant and better prepared for the next energy crisis.

You are misrepresenting climate science. Climate change does not have "Catastrophic" consequences. It has negative economic onsequences but they are small compared to other factors. For a temperature change of 2.7 degree C the negative impact will be about 2 % of global GDP at a time when global GPD is 5 to 10 times higher than now:

You are also misrepresenting the complexity and costs of using intermittent socalled renewables as wind and solar. Which can not supply a modern society with energy without backup, which makes them prohibitively expensive.

All said and with Nordhaus a forced planeconomic net-zero policy wil make the global society much worse of than global warming, which a rich and smart world easily and cheaply can adapt to:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340900993_Welfare_in_the_21st_century_Increasing_development_reducing_inequality_the_impact_of_climate_change_and_the_cost_of_climate_policies

From where are you pulling the statement that a 2.7 degree Celsius increase will be "displacing tens or hundreds of millions of people"? This seems like a far-fetched and low quality post compared to the excellent stuff you usually post. Please do better than this, Joey!