Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 17,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

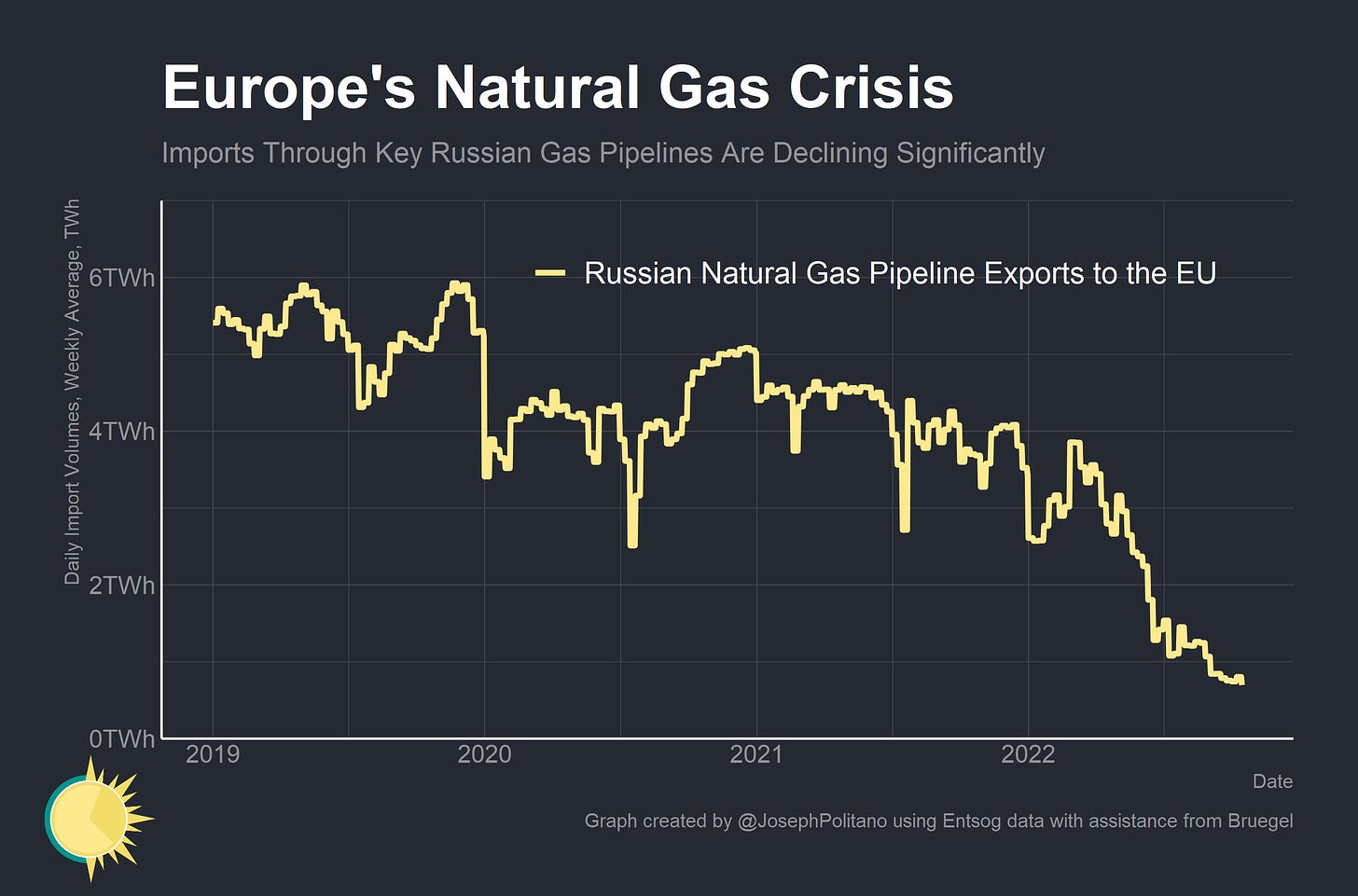

Even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine early this year, European countries were dealing with an acute energy shortage. Supplies of Russian natural gas to the EU were much lower in 2021 than they were before the pandemic—leading to surges in prices and widespread inventory drawdowns. When the Russians invaded Ukraine shortage became crisis as the continent faced the possibility that Vladimir Putin could further cut Europe off from Russian natural gas. As the war dragged, sanctions bit the Russian economy, and Ukraine’s military position improved, Putin decided to weaponize gas supplies and cut off large chunks of Europe. Flows through some key pipelines have now dwindled to zero—the most recent notable example being the shutdown and subsequent possible sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines linking Russia to Germany—leaving many nations in a precarious position.

Natural gas, unlike other energy commodities like oil or coal, does not have an entirely globalized market. To be transported across the ocean natural gas needs to be liquefied, cooled, and condensed at specialized export facilities and then be re-gasified at the destination. The facilities to export liquefied natural gas (LNG) have limited capacity, and the infrastructure to regasify LNG shipments are not omnipresent. Germany had no regasification capacity before this year, and it alongside other European nations has worked to acquire floating storage regasification units (FSRUs) as soon as possible.

So when the Russian invasion caused oil prices to spike it was felt by all nations somewhat equally—but the extreme relative difficulty in transporting natural gas across oceans means that Europe is suffering the brunt of the natural gas shortage. Given that natural gas is a critical component of home heating, cooking, electricity, and critical industrial processes the big question remains—as Winter approaches how bad will European natural gas shortages be?

Stocking Up for the Winter

The good news is that the worst-case scenario now seems less likely. Thanks to fortuitously warm weather, a big fall in Chinese LNG demand, and non-price rationing imposed by many national governments, European natural gas futures prices for this winter have plummeted from their peak. Make no mistake, the shortage is still acute—prices have risen nearly tenfold from their pre-pandemic level, and again some of the pain is borne through nonprice rationing—but there has still been a noteworthy improvement in this winter’s outlook over the last couple of months.

Diligent refilling of natural gas storage facilities throughout the continent has also contributed to the improved outlook—as of today, every major EU country has hit the bloc’s 80% target and overall storage levels sit at a highly respectable 93%. Germany has surpassed its more ambitious target of 95%, and storage facilities in France are more than 99% full. Critically, the warmer weather has partially enabled storage levels to continue growing so far this October. Cuts to natural gas consumption during the summer, switches to coal and oil, and increased LNG imports have enabled the EU to better weather the withdrawal of Russian natural gas supplies.

Trying to Replace Russia in the Aggregate

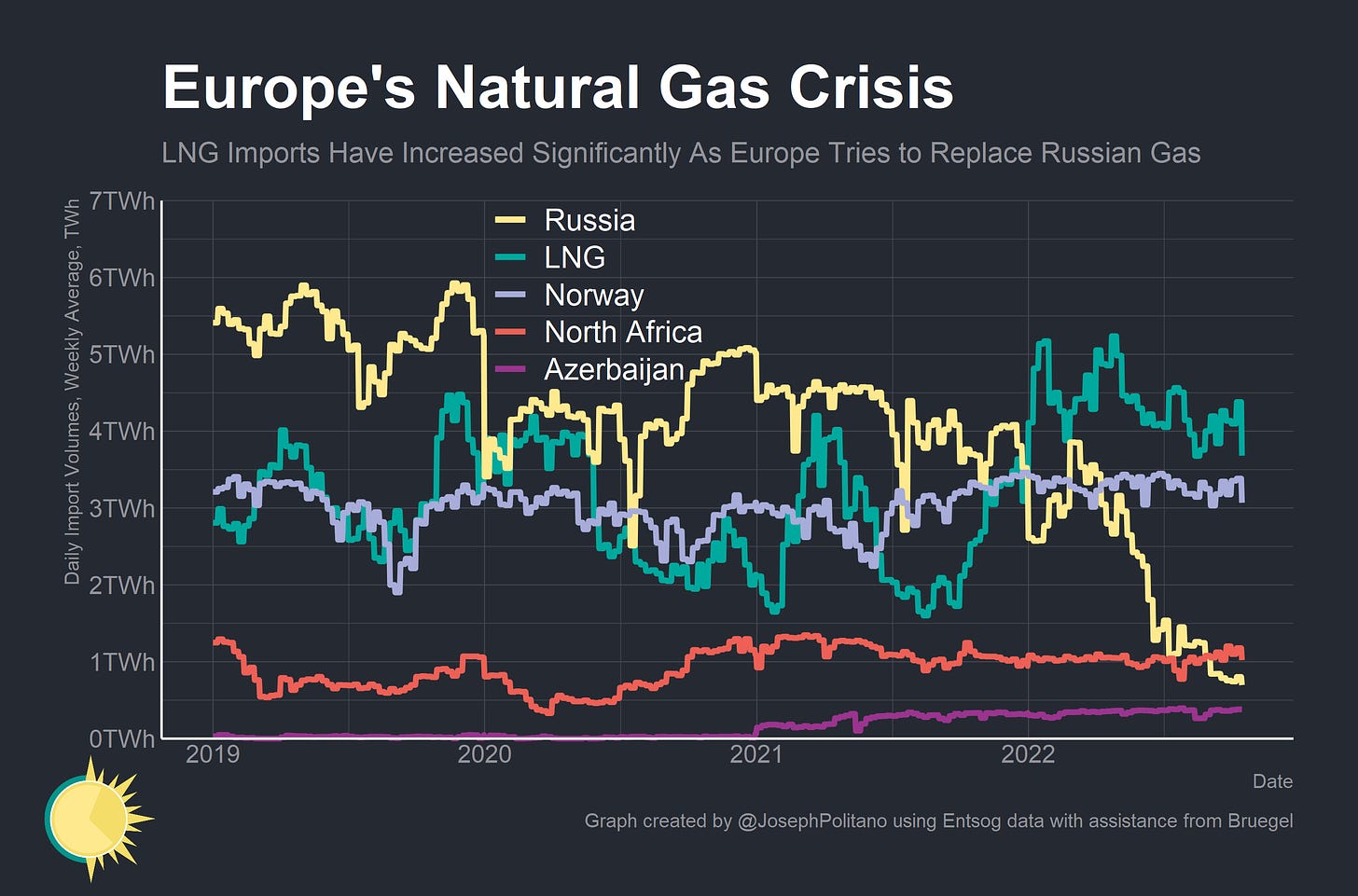

Indeed, total LNG imports to Europe1 have been highly elevated since the start of this year as the continent works to replace Russian supplies. The demand to refill storage facilities broke the normal seasonal patterns of LNG imports—meaning facilities have been operating closer to full capacity throughout the vast majority of this year. Europe also got lucky that a slowdown in the Chinese economy and reimposition of lockdowns occurred also just as the Russian invasion began—as dropping Chinese LNG demand has afforded more space to European buyers.

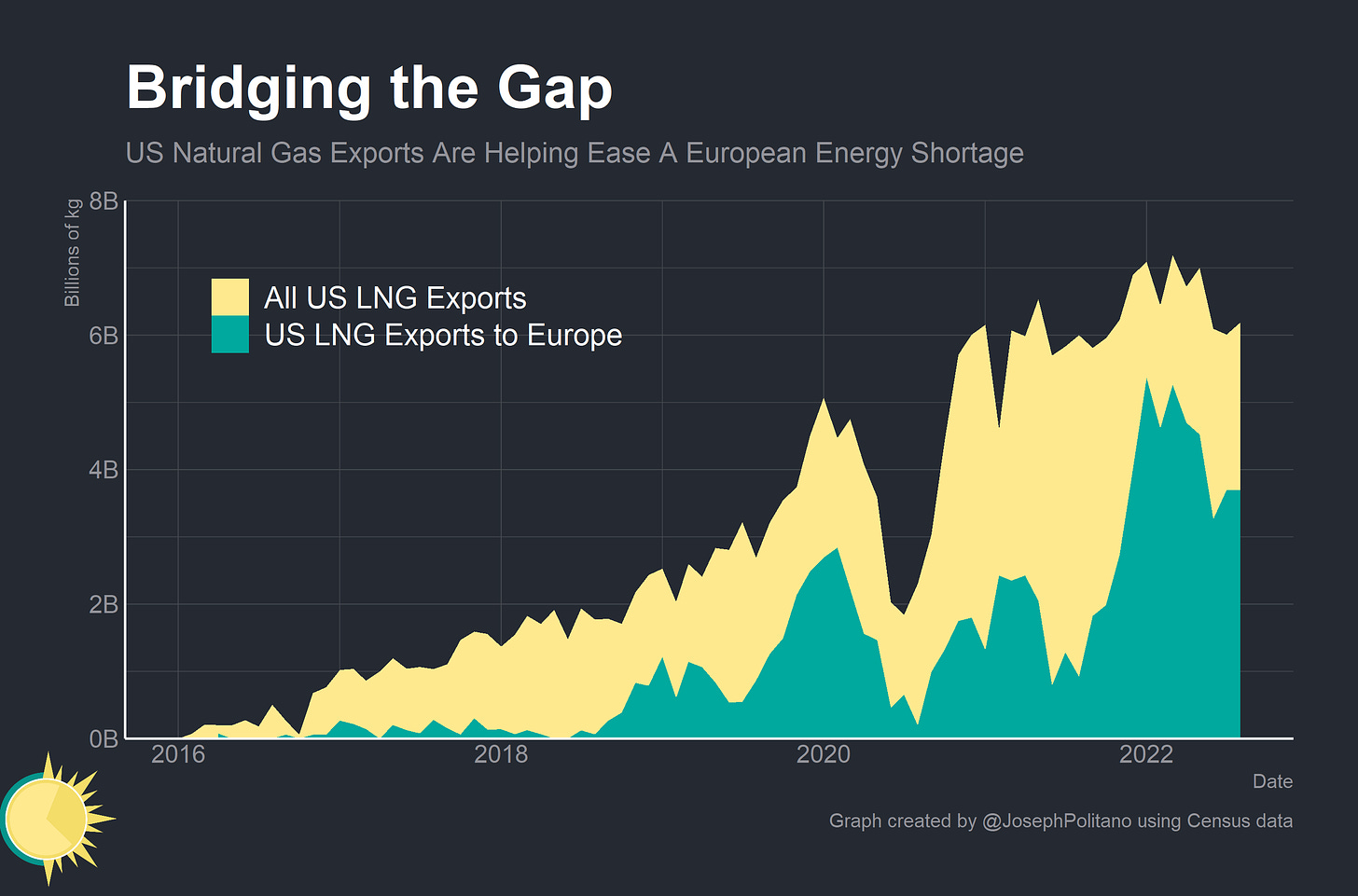

A large chunk of the LNG supplies delivered to Europe2 come from the United States, which just this year surpassed Qatar and Australia to become the world's biggest LNG exporter. In some months early this year, nearly 75% of US LNG exports were destined for European shores—and American gas made up more than 50% of European LNG imports in the first half of 2022. The fire and ensuing shutdown of the Freeport LNG facility (which makes up nearly 15% of us LNG export capacity) in Texas has hampered shipments since June, but at least partial service is expected to resume there next month.

It’s not just LNG though—European countries are also importing more through non-Russian pipeline networks. Increased pipeline natural gas flows from North Africa (mostly Algeria), Norway, and Azerbaijan (through the relatively new Trans-Adriatic pipeline) are also helping alleviate the natural gas shortage. Combined with rising LNG imports, they have mostly offset the drop in Russian supplies—though at great cost.

The Slow Burn

Combined, that may make the situation seem relatively optimistic this winter—but it is worth remembering how dangerous today’s shortage would be perceived against the pre-pandemic counterfactual instead of the worst-case-scenario counterfactual the EU was facing earlier this year. There are still risks that gas supplies could sink below critical levels and trigger rationing policies in many countries.

The natural gas shortage is likely to extend beyond this year too—current natural gas futures data suggests highly elevated prices through 2024, elevated prices through 2026, and a new normal of 2-3x pre-pandemic prices through 2032. Getting more LNG capacity online will take time and significant investment—the US Energy Information Agency expects a 33% increase in export capacity over the next 3-4 years but significant new liquefication capabilities are only expected to be online by 2024.

The continent’s problems aren’t limited to natural gas either. French nuclear energy output—which provides 75% of the nation’s electricity—is expected to remain below normal levels through 2024 due to corrosion and maintenance issues. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s decided to extend the lifespan of several reactors in his country—but only through this winter. A mixture of luck and dedicated policy has helped the EU improve its energy position recently—but it is still facing a problem that will last longer than this winter.

More precisely, this data looks at the EU plus the UK

This data looks at the broader European continent—that is, including Turkey, Russia, and other non-EU members

Brilliant round up of the gas situation in Europe.

It is really interesting to see how the market reacts and how new suppliers start to ramp up, consumers adapt and alternatives are found. Economics in actions.

Thanks for the great post.

Great post! Been super fascinated by this whole European energy crisis since it started earlier this year, but I didn't know they were heading for it anyways. That was super interesting. Looking forward to more post from you in the future!