Evaluating Recession Risks Amidst Inflation

And Charting the Inextricable Links Between the Two

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 17,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Since the start of this year, the two big questions in the global economy were “when will inflation return to normal?” and “what are the chances of a global recession?” Of course, the two questions are inextricably linked—more persistent inflation increases the Federal Reserve’s tolerance for recession risks, and higher recession risks taper the demand-side pressure that drives up short-term inflation.

Still, the end result is that month-to-month fluctuations in US inflation data carry unusually massive importance for the global economy. This was rather evident when lower-than-expected inflation figures from the Consumer Price Index (CPI) caused a large rally across stock and bond markets earlier this week—the data was good enough that market participants’ recession concerns alleviated significantly in its wake. Rate-setting officials at the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) also recently added some dovish language to the statement accompanying their most recent meeting and signaled more willingness to slow the pace of interest rate hikes at upcoming meetings.

Make no mistake, though, recession risks remain elevated in the medium term—the base case laid out by Federal Reserve officials is still that economic pain is necessary to fight inflation. Whether the pain we’ve already experienced will be enough and how much pain will be required going forward will come down to how upcoming inflation data shakes out.

The Good(s) Data

This week’s inflation data came in under expectations thanks to several factors—not least of which was a significant downward pull from core goods prices. This is only the third month since the start of 2021 that core goods prices declined, and the drop in prices was larger than any monthly decline US core goods prices saw from 2002-2019.

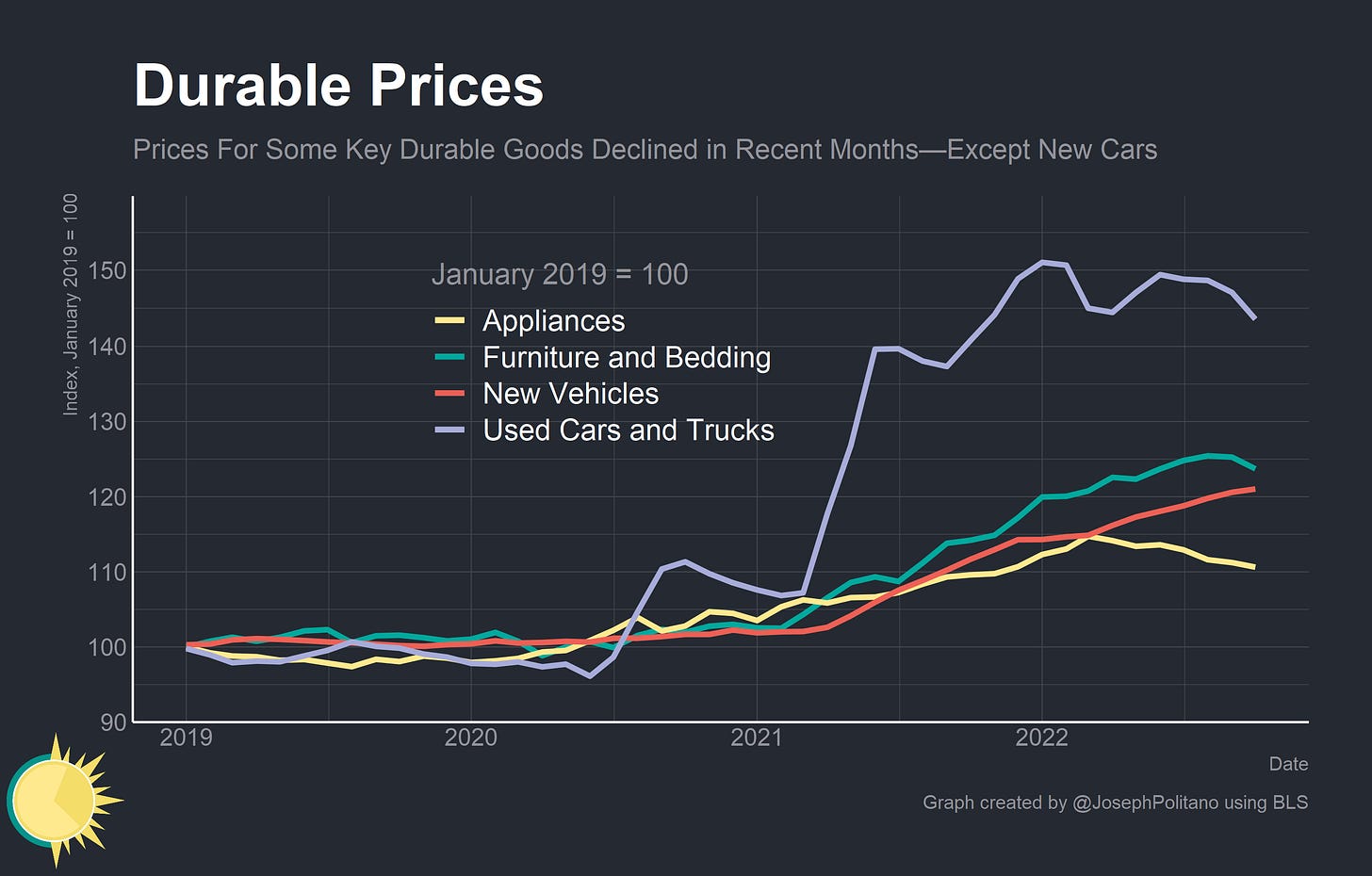

Prices for several key durable goods categories have been falling for a couple of months now—the big contributors to October’s price drops were appliances, furniture, and used cars and trucks. Drops in the former two categories are both indirect consequences of the renormalization of consumer spending (most people only need so many tables, and purchases of furniture and appliances jumped up during the pandemic) and direct consequences of tighter monetary policy (higher interest rates hit homebuilding especially hard, which pulls down demand for durable home goods, which also are often directly financed by consumers).

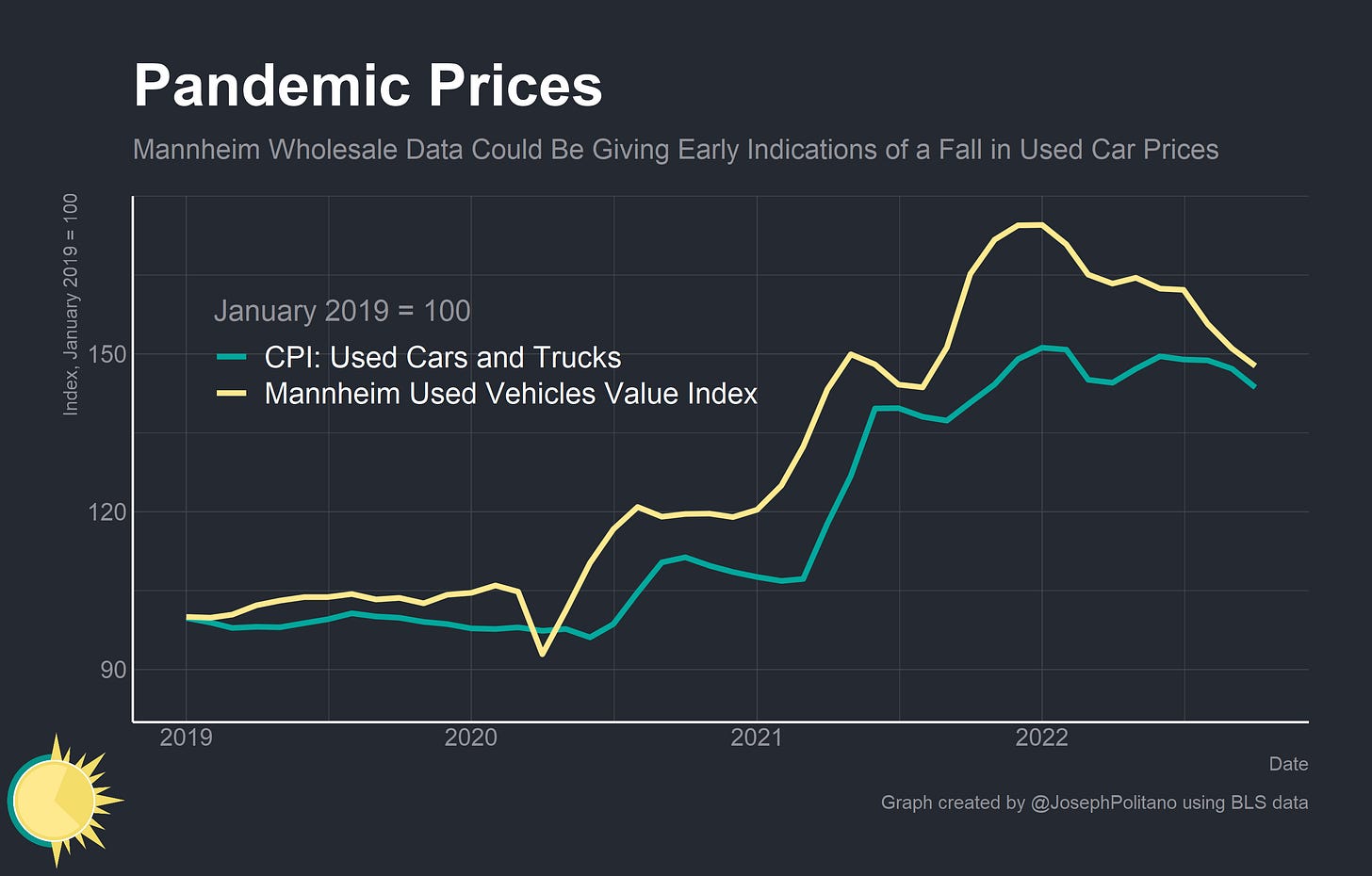

The drop in used vehicle prices is arguably most consequential though—used vehicles make up a comparatively larger chunk of the CPI weighting and rose more in price during the early pandemic. The drop last month was the third-largest monthly decline since 1970, with the second-largest coming earlier this year. Wholesale used car prices have been declining since January and new car production has been improving throughout this year, so it’s possible more declines could pass through to retail prices soon.

Durable goods—although they are extremely important as an economic indicator and are responsible for a disproportionate chunk of the excess inflation since 2020—are far from the largest contributor to today’s inflation. With gas prices down from their summer highs and supply improving for many critical goods, year-on-year inflation is now mostly driven by increasing core services prices.

Housing prices make up about 1/2 of core services, and price growth here remains high (though it decelerated a bit from last year). The nature of rent inflation methodology means that official data lags directional movements in new leases by about a year—and the good news is that the most recent data from ApartmentList showed significant declines in rent prices over the last two months. In fact, the drop in October was the sharpest month-on-month decline in ApartmentList data’s 5-year history. It will take a significant amount of time for that to pass through to official data, and the exact relationship between private data movements and inflation is hard to measure, but it is at least some more encouraging news on core inflation.

Still, even stripping out many of the volatile or lagging components, inflation is uncomfortably high. Excluding food, shelter, energy, and used vehicles, year-on-year inflation remains at 6.3%. This metric has slowed significantly over the last few months but remains relatively high—on an annualized basis, it has increased 5.3% over the last three months. Since it exemplifies many of the cyclical inflation components that the Federal Reserve theoretically has more control over, its high growth rate is likely disheartening to FOMC officials—and is part of the reason they aren’t letting up on rate hikes yet.

Rating Recession Risk

So price growth has slowed but remains well above the Fed’s targets despite lower-than-expected CPI prints. That’s bad because we’ve already suffered significant real economic pain in fighting inflation—a number of leading economic indicators like employment growth, household consumption, fixed investment, and more have weakened significantly over the last few months. If bending the economy only got inflation down so far, is breaking it the only way to stop today’s inflationary surge?

The good news is that recession risks have actually likely abated significantly since the summer. At first, this was due to real economic improvements and alleviation of supply-side constraints—gas prices fell back down, payrolls continued growing, Europe’s energy situation improved, and domestic production of critical goods like motor vehicles picked up. Relative to the shift in interest rates and financial conditions, the real economy has also held up pretty well. More recently, it has been due to encouraging inflation and inflation-related data—interest rate volatility tanked in the wake of this week’s inflation print, for example. The combination of easing financial conditions accompanied by lower market-based inflation expectations is exactly the kind of thing the Federal Reserve wants to see in a soft-landing scenario.

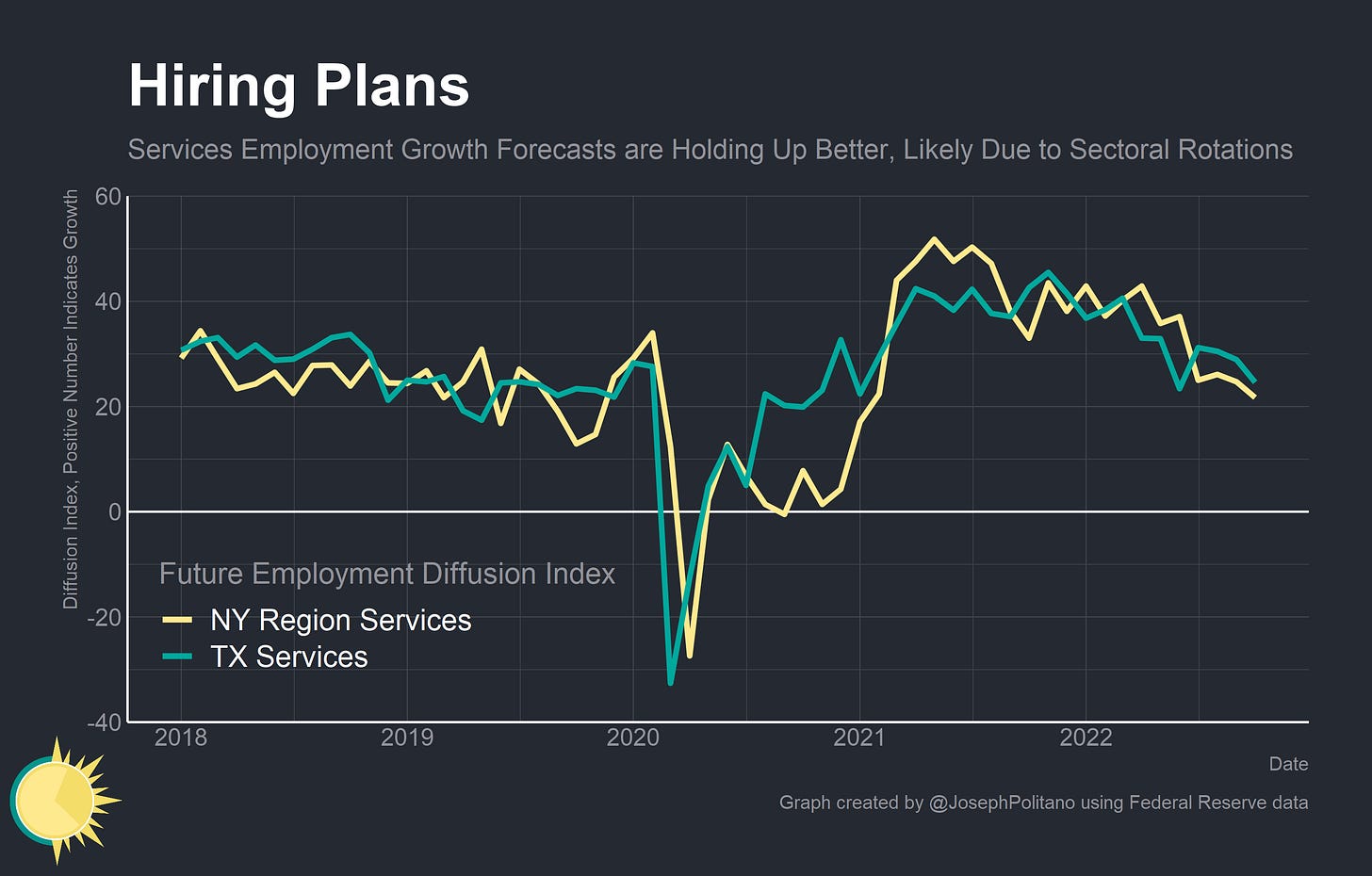

Business employment forecasts have also held up fairly well—though they have declined notably. Manufacturing firms across three different regions still expect employment growth for the foreseeable future, though the pace of hiring is definitely slowing.

The same can be said of service-sector employment forecasts, which are declining even less and holding up even better likely in part due to the slow, ongoing demand rebalancing away from goods and towards services.

Even residential construction—a sector that should be hit doubly hard by interest rate hikes and real economic slowdowns—has held up fairly well so far. Employment growth has stalled, but hasn’t fallen since mortgage rates started surging earlier this year. That’s despite a 25% drop in new housing starts! So far, the backlog of under-construction homes has been able to support the industry’s employment.

A number of other indicators are also flashing yellow, not red (yet). Employment growth has slowed down significantly but hasn’t meaningfully declined. Sales for heavy trucks, a key indicator for the transportation sector and thereby consumer demand, have held up fairly well. Initial unemployment claims still remain low. High-yield credit spreads, which proxy for the default chance for risky major companies, remain elevated but are no worse than in late May. Overall, recession risks are lower than they were earlier this year.

Conclusions

That’s not to say everything is looking rosy—forecast aggregators have seen recession chances decline significantly over the last four months but the estimated odds are still about 50% for each of the next two years. The Federal Reserve still likely believes a recessionary increase in the unemployment rate is necessary to tame today’s inflation, and they have continually emphasized the centrality of inflation in their rate-setting decisions to the exclusion of many real economic variables.

It’s also worth remembering that recessions aren’t just a binary decisions by the National Bureau of Economic Research. There’s a world of difference between and within recessionary and non-recessionary outcomes—and the scale of slowdown the US economy sees will vary dramatically depending on how much declining economic output compounds on itself.

The core dynamic, though, remains mostly unchanged—inflation data will determine the stance of monetary policy and the stance of monetary policy will determine recession risks. The best-case scenario is that inflation continues to come in lower than expected like it did this week.

I think on Thursday markets were pricing in the increased chance of a soft landing, though I think the Fed will put us into a recession anyway. Demand destruction will be the next headwind for companies, and that’s really what the CPI is starting to show. I’m not a bear but I think the markets might be a little to optimistic on a soft landing. In the long run stocks are still cheap and that will provide tailwinds.

Terrific and organized data on where we stand right now. Thanks Joseph.