Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 15,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

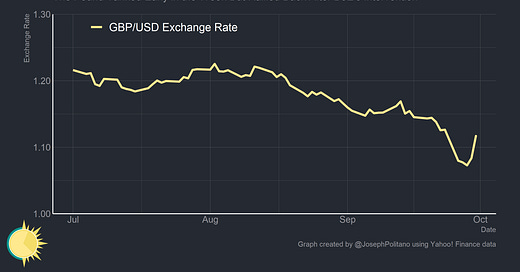

This week, new UK prime minister Liz Truss announced her proposed “mini-budget,” a package of tax cuts, investment incentives, and energy subsidies designed to increase economic growth and help the UK out of its economic malaise. The response seemed, to say the least, unenthusiastic—the British pound fell precipitously against the dollar, and yields on gilts (UK government bonds) skyrocketed. The chaos got so bad that the Bank of England was forced to step into gilt markets out of financial stability concerts.

The package is, in my opinion, a mixed bag that leans bad overall. The energy policies were a necessary and inevitable response to the massive rise in European natural gas prices and some of the investment incentives will help support growth—but implementing large regressive tax cuts to stimulate aggregate demand while inflation sits at nearly 10% isn’t a great plan to say the least. Outside of gas prices, the Truss government seems to be leaving inflation-fighting entirely up to the Bank of England—and is willing to force them into raising interest rates even more in order to counteract the government’s fiscal plans.

However, I want to put aside most of the specifics of the Conservatives’ new budget for a moment here—if only because I think there has been an overemphasis on it as the sole driver of recent market movements. After all, Truss was not exactly secretive about her plans during the Tory leadership election and markets should not have found the contents of the mini-budget entirely surprising as written. In other words, the market movers aren’t all Truss—the Bank of England and Federal Reserve both met on September 21st to raise interest rates by 0.5% and 0.75%, respectively, shifts in energy prices, the dollar’s value, and the global economic outlook have jostled markets, and in general bonds and currencies have been trading with extreme volatility in recent months. The chaos in British markets is much more interesting as representative of the variety of global phenomena than as a narrow response to a bad budget.

London (Margin) Calling

Most of the financial rules, regulations, and norms of the last 15 years have only existed during a regime of extremely low interest rates and large central bank balance sheets. Throughout the last decade, there has been a consistent pattern whereby a catastrophic or near-catastrophic event exposes a risk in the financial system that policymakers then rush to cover—and those financial mishaps tend to happen more when the modern financial-regulatory regime enters new territory. Rapidly rising rates and shrinking balance sheets are, in many ways, new territory.

When repo rates—the interest paid in the short-term collateralized cash lending market—spiked in late 2019, the Federal Reserve was forced to inject massive amounts of liquidity into the market. Eventually, Fed officials made a standing repo facility to ensure rates remained within acceptable levels and prevent another crisis. When the European Central Bank started raising rates earlier this year the yields on Italian and Greek bonds started skyrocketing—so the ECB intervened with an (imperfect, to say the least) tool designed to contain sovereign bond yield spreads.

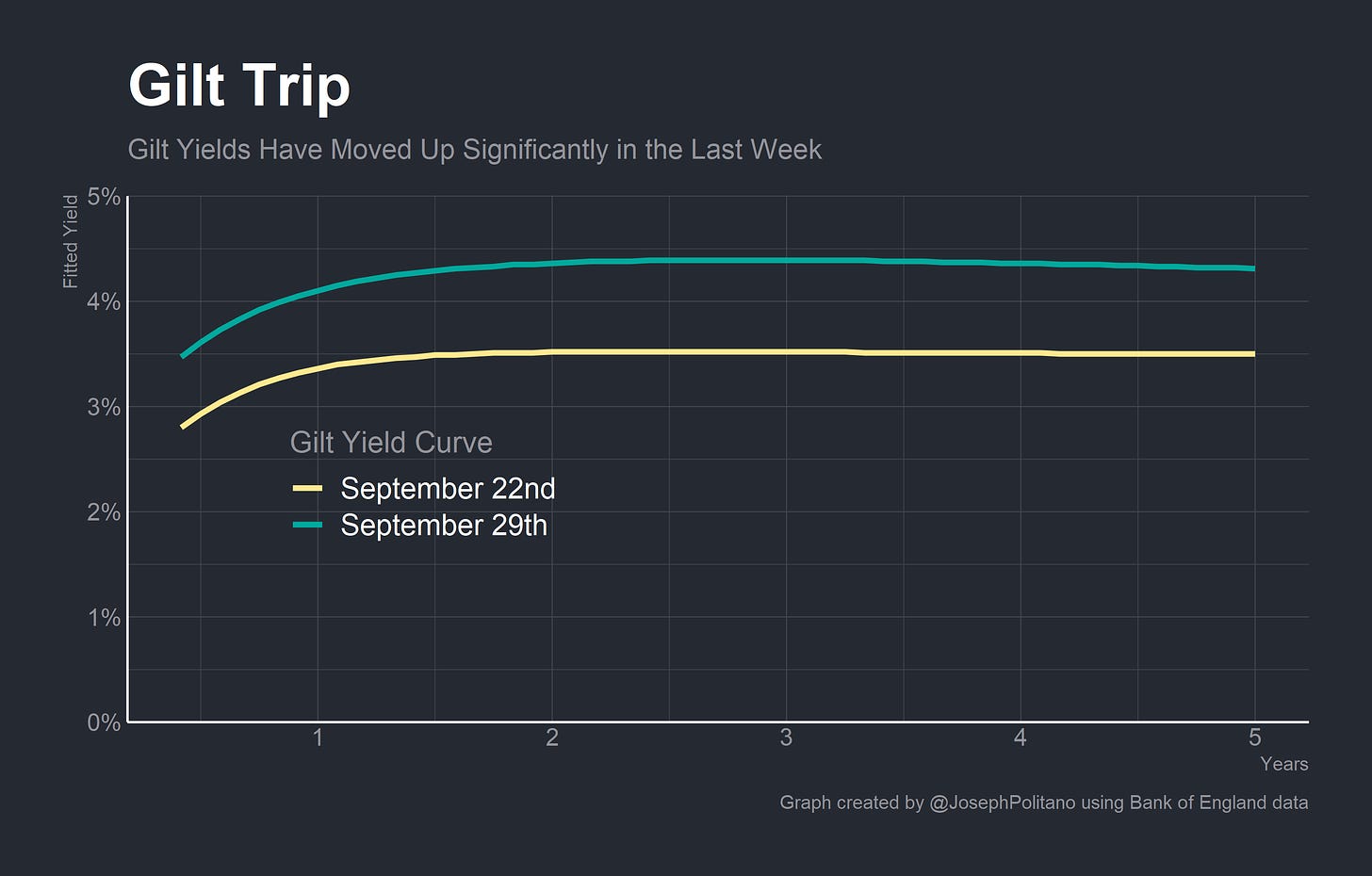

The massive movements in gilt yields seem to have been driven by the margin calls of a significant number of Liability Driven Investment strategies at pension funds across the UK. The details are interesting and worth discussing, but the simple version is that these funds owned long-dated gilt assets and usually levered their gilt investments. When gilt prices declined they got margin called and creditors forced them to post more collateral, which forced them to sell gilts, which pulled prices down, which caused more LDI strategies to get margin called, and so on and so forth until 30-year gilt yields were up from 3.7% on the 23rd to 5% on the 27th. At that point, the Bank of England was forced to intervene in markets and gilt prices rose again, with the 30-year yield dipping to 3.8% as of writing.

It reveals one of the trade-offs central banks face in setting policy—they want to be perceived as credible and fast-acting by markets, but if their reaction function is too forceful and rapid they run the risk of bumping into an unforeseen financial risk. Move slower and you lower the risk of financial problems, move faster and you lower the risk of inflation problems.

Can’t Buy Me Love

During the Great Recession and Coronavirus Pandemic, a large number of central banks engaged in Quantitative Easing (QE) programs whereby they would exchange short-term central bank liabilities (bank reserves) for long-term central government liabilities (government debt, e.g. treasuries or guilts) and/or Mortgage Backed Securities. Their goal was to stimulate demand while interest rates were stuck at or below 0% through the direct and indirect effects of these asset purchases—lowering long-term interest rates, improving financial liquidity, facilitating more private-sector risk-taking, and lowering the duration of private-sector assets. Now that inflation-fighting is the primary goal of central banks, many have begun to actively reverse the QE programs they had previously undertaken—a process dubbed Quantitative Tightening (QT).

When the Bank of England announced that it would be buying gilts to stop the crisis there was a lot of ink spilled about how they were wrongheadedly “restarting QE” with inflation at 10%. But this fundamentally misses the point of QE, QT, and BoE’s recent actions. The move in gilts was partially caused by financial stability issues, and time-delineated asset purchases intended to address financial stability issues are not the same as large asset purchases intended to address macroeconomic issues. Besides, the clearest causal channel of QE is through long-term interest rates—which are still elevated from their levels earlier this week. The idea that tighter monetary policy should be allowed to manifest as unnecessary financial instability rather than higher interest rates is not one with many friends.

Additionally, though most central banks do not currently treat it that way, the yield curve is a policy choice—interest rates are functionally downstream of their policy decisions. Even if the BoE was performing QE there’s nothing inherently wrong with using asset purchases to signal that 5% 30-year yields are unacceptably high—if you think British monetary policy is too loose your disagreement is with the structure of the yield curve more than the tools used to get there. In other words, the BoE’s actions were about fixing financial flaws not bailing out a bad budget.

The nuanced argument for “QE has to continue forever” rests not on the idea that central banks are subsumed by fiscal dominance and must “fund” yawning budget deficits, inflation be damned. Instead it rests on the idea that, for a variety of bank regulatory and financial stability reasons, the lowest comfortable level of reserves (or, what BoE policymakers define as the Preferred Minimum Range of Reserves) in the banking system might be much higher than anticipated. If commercial banks need more reserves than expected, central banks would have to revise down their estimates for Quantitative Tightening. Bank of England’s estimates would probably have to be way off—pre-pandemic it believed the Preferred Minimum Range of Reserves to be in the £150-250B range compared to the £942B in reserves today. Still, it’s another way that monetary tightening could risk significant hiccups in the financial system.

Bear-Wolves of London

In the mid-to-late 2010s, a line of argument among many macroeconomists emerged that went something like this:

The government's purpose is to maximize the welfare of its citizens, which in practice means maximizing economic growth while managing inequality.

During normal times, governments do this best by managing critical public investments (healthcare, education, defense, etc) and only borrowing money to the extent that their public investments and redistribution are more beneficial than the private investments and consumption they “crowd out” by borrowing.

These (the mid-2010s) are not normal times—a large amount of labor and capital remains idle, as evidenced by high unemployment rates, low rates of investment, and below-target inflation. Interest rates are stuck at-or-below 0%, government bond yields are at historic lows, and central banks are struggling to boost aggregate demand.

Therefore, increasing central government deficit spending, almost regardless of what it is spent on, will boost economic growth much more than it crowds out investment. We should pass large borrowing and spending packages to boost aggregate demand, which will boost growth by so much that the government will be more than able to service the new debt it has incurred.

Even when the economy returns to something resembling pre-Great Recession growth and employment levels, a large amount of consistent deficit-financed fiscal spending will be necessary just to keep nominal interest rates above 0%.

Since real interest rates are so low, government investments that provide relatively meager net benefits or only reap dividends far into the future can pass a long-term cost-benefit analysis.

In truth, there is not much novel about this line of argument. The idea that fiscal policy should be used to manage the business cycle goes back centuries, and the idea of a “fiscal multiplier” where government spending induces more economic activity than solely its direct effects goes back almost just as long. The new parts of the argument were twofold. The first part, which I tried to articulate and advocate for in a previous piece, was that because short-term rates were zero and long-term rates were so low, government deficit spending was an essential part of interest rate stabilization. Without it, countries would permanently struggle to achieve their growth and inflation targets, and interest rates would always be stuck near zero. The second part essentially just said that governments should use lower discount rates when evaluating investments.

Today, nearly every country has been forced out of the zero lower bound by rising global inflation and the US-led global rate-hiking cycle. Real interest rates are rising to levels not seen since the start of the Great Recession, and the problems of today rest primarily on shortages, not underutilization, of capacity. In such an environment, the kind of scattershot stimulative fiscal shocks the mini-budget represents are counterproductive—and unfunded fiscal policies in general deserve more scrutiny. I don’t want to completely oversell this last point—real interest rates remain low by historical standards even alongside expectations for large long-run deficit spending across high-income nations. But it’s true that the net effect of the new stimulative measures in Truss’ plan is likely to just further box the Bank of England into a situation where they have to risk a recession in order to combat inflation. The flexibility for massive deficit packages that central governments “enjoyed” as a result of weak economic growth in the 2010s has largely dissipated today.

Nice summary. I think your key initial point is on target - the disarray in gilt-edged markets was probably less about the new government's policy announcements than the lurking "financial instability" (I hate that term) issues in an environment where rates are increasing rapidly after a long, near-zero period. We hear similar concerns from bond-market pros in the US.

Fabby job squire.