Good News is Bad News

Understanding Today's Topsy-Turvy Economy and the Fed's Reaction Function

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 14,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Paid annual subscriptions are 20% off to celebrate the newsletter’s launch! Other discounts are available for students, teachers, government employees, journalists, and any groups of four or more.

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

The greatest Yogi-ism in finance is “Good News is Bad News”—and its converse “Bad News is Good News.” When most people talk of the good-news-is-bad-news paradigm, however, what they’re primarily talking about is the market’s expectations for the reaction from the Federal Reserve. A better-than-expected jobs report is good news, but equity markets can often sell off in the aftermath of such news because it means the Federal Reserve is likely to raise rates more in reaction to a stronger labor market. A weak GDP report is bad news, but equity markets can rally in the aftermath if it makes the Fed more likely to lower rates to try and prevent a recession.

Obviously, this is oversimplifying a bit—financial markets and global economies are complicated interconnected systems, so it shouldn’t be surprising when what’s good for the goose isn’t necessarily good for the gander. However, it is still true that the “meaning” of a lot of economic news is colored by the market’s meta-reaction to that news, which itself is colored by the expected reaction from the Federal Reserve. Understanding the reaction function of today’s FOMC is therefore key to understanding which bad news is good and which good news is bad.

Over the last couple of months, we have experienced a dynamic whereby a lot of good news—the drop in gas prices, rising consumer sentiment, and strong jobs reports—are treated as bad while a lot of bad news—tightening financial conditions, deteriorating business outlook, and elevated recession risk—are treated as good. Arguably, a stronger-than-expected overall economy (good news!) has mixed with worse-than-expected inflation data (bad news!) to engender significant increases in expected short-term interest rates and slightly tighter monetary policy, keeping recession risks elevated.

Good News is Bad News

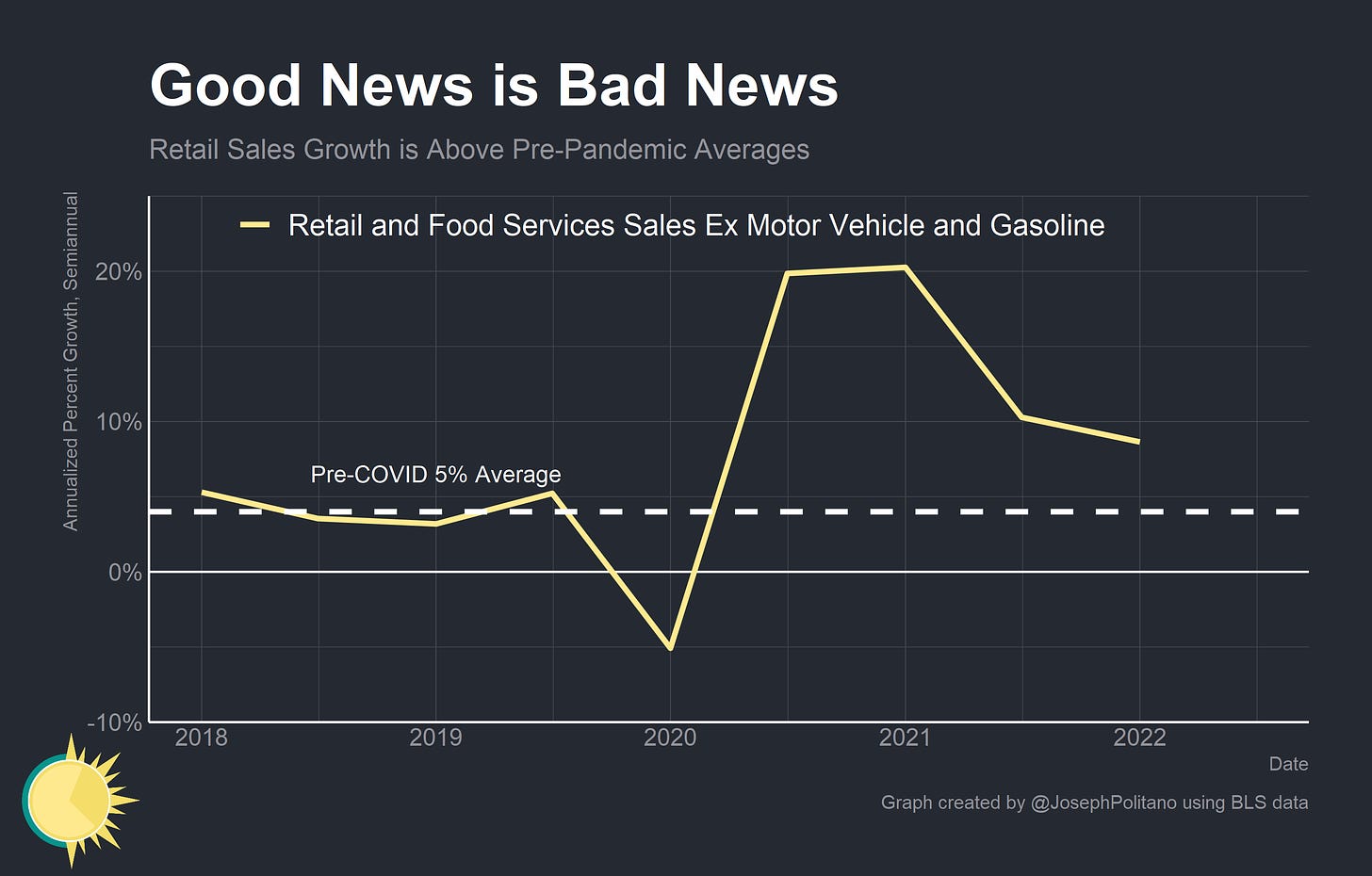

The biggest source of “good news that’s bad news” comes from the labor market. The Federal Reserve wants to get inflation down, and in doing so wants to see aggregate income growth moderate towards the 5% per-year level from before the pandemic. So the fact that aggregate wage growth still remains elevated by pre-pandemic standards is not welcome news to them—higher income growth means higher spending growth, and higher spending growth means higher inflation.

Indeed, some of that strength is apparent on the spending side—retail sales growth remains strong even when excluding currently-volatile motor vehicle and gasoline sales. That kind of ongoing demand pressure is going to have a strong upward pull on price growth even if supply-chain and production conditions improve.

In fact, even the improvement of real supply conditions can engender a negative policy response. Take gas prices—the major shock to energy supplies at the onset of the Russian invasion of Ukraine was clearly bad from a purely economic perspective because of the large shortage of such critical economic inputs, but the Federal Reserve also felt forced to respond to higher gas prices (bad news!) with higher interest rates (bad news again!) due to the possible effect on inflation expectations.

Core inflation is something we [on the Committee] think about because it is a better predictor of future inflation. But headline inflation is what people experience. They don’t know what core is. Why would they? They have no reason to. So that’s—expectations are very much at risk due to high headline inflation. So it’s become—the environment has become more difficult, clearly, in the last four or five months, and hence the need for the policy actions that we took today. Hence our resolution to get rates up and, ultimately, get them to where we think they need to be in coming months.

Jerome Powell, June 15th Press Conference

Gas prices have slid back down since then, bringing inflation expectations down with them. So mission accomplished, and the pace of rate hikes will be slowed? Maybe a little bit—markets perceived lower inflation expectations in the University of Michigan survey as a signal that a 100 basis point interest rate hike at the next FOMC meeting was less likely.

But that’s not the full story—as I discussed in my earlier piece on inflation expectations, households often interpret lower gas prices as signs of an improving economy and react by raising their sentiment. Rising consumer sentiment can instill the confidence needed to go and make major purchases, the exact behavior the Federal Reserve hopes to prevent right now. To be fair, sentiment still remains low by historical standards, but that doesn’t stop falling inflation expectations from arguably being part of the good-news-that’s-bad-news dynamic.

The second takeaway is that the fears of a recession starting in the first half of this year have faded away and the robust U.S. labor market is giving us the flexibility to be aggressive in our fight against inflation. For that reason, I support continued increases in the FOMC's policy rate and, based on what I know today, I support a significant increase at our next meeting on September 20 and 21 to get the policy rate to a setting that is clearly restricting demand.

Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller, September 9th Speech

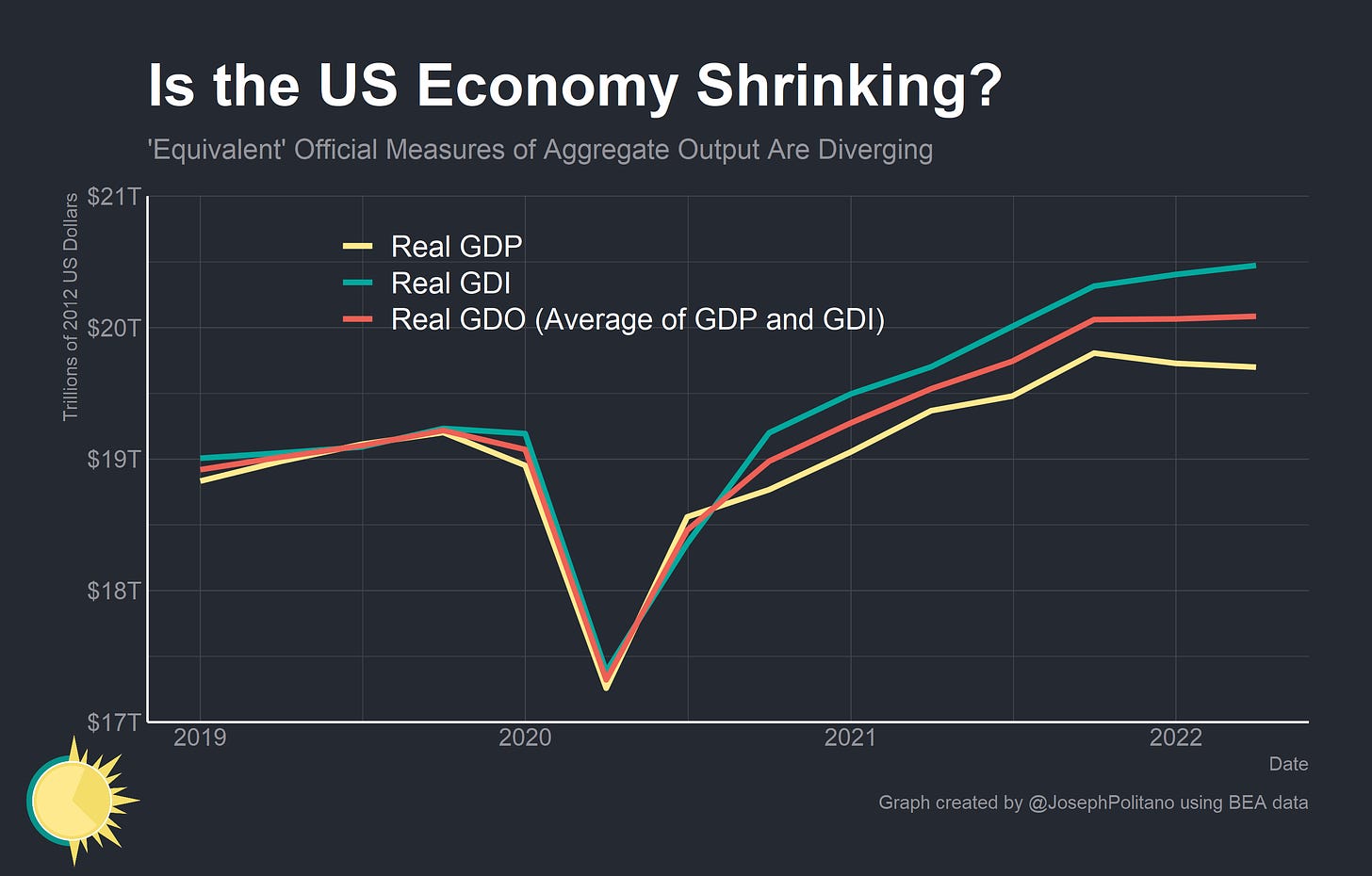

The story of aggregate output growth over the last few quarters can also arguably be told with the good-news-that’s-bad-news dynamic. Real GDP growth was negative during the previous two quarters, prompting rising recession fears and arguably leading to some hesitation among members of the Federal Reserve about pursuing aggressive rate hikes. When more good data on income, employment, spending, and production came in throughout the year the consensus shifted towards higher interest rates and tighter policy.

Bad News is Good News

Okay, what about the inverse? What kind of bad news could become good news based on the Fed’s reaction to it? In theory, one example came hidden in last month’s jobs report. Even though job growth was relatively strong, the unemployment rate rose from 3.5% to 3.7%. That wasn’t from a reduction in workers with jobs but rather from an increase in the number of people without jobs who were actively looking for work.

To be clear, one report is not enough to draw a trend from (especially when unemployment data can be so volatile). But a situation in which wage growth mediates through labor supply improvements rather than labor demand destruction is the Federal Reserve’s best-case scenario for the job market. So rising unemployment can also be bad news that’s actually good news.

Similarly, if the Fed wants inflation to come down without a recession it’s going to have to force lower relative demand, which would likely manifest as worsening business conditions and output. That’s mostly what we see in recent data, and it may be part of the reason why business unit-cost inflation expectations have started to fall in recent months.

I was actually happy to see how Chair Powell's Jackson Hole speech was received. People now understand the seriousness of our commitment to getting inflation back down to 2%.

Those worse demand conditions are partially created through—and partially signaled by—tighter financial conditions. Fed officials have been explicitly aiming for worse financing environments across the board as evidence that their interest rate changes are having the intended effect of cooling demand. But fundamentally tighter borrowing conditions for major companies move hand-in-hand with a worsening macroeconomic outlook and elevated recession risks. So rising high-yield credit spreads—a proxy for credit conditions for the riskiest major corporations—are both good news in that they signal a weaker demand outlook and bad news in that they signal a higher chance of an economic crash.

What Makes The News Good?

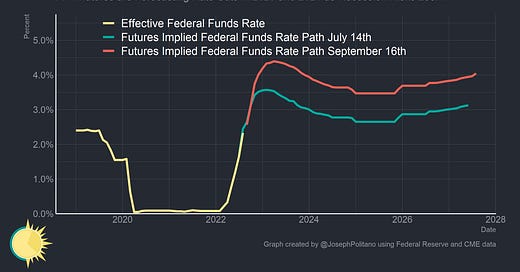

Fed officials have been recently talking up higher rates for longer and have all but explicitly tried to force market participants to stop expecting interest rate cuts in 2023. To some degree they have been successful—markets now only project tiny overall rate cuts in calendar 2023 (though mostly this comes from some expected hikes early in the year). Whether that reflects a stronger overall economy that can withstand higher rates or an overly-aggressive Fed remains to be seen. Bad news is good news is bad news, and so on and so on.

The Fed will repeat that it is a data-driven institution, and that is definitely true—but it’s always worth remembering that data is interpreted through the lens and goals of the institutions and people who create and consume it. What’s good news or bad news depends entirely on how you look at things, and right now the Fed is looking at things almost entirely based on how they will affect inflation; data points that suggest higher-than-expected inflation are bad news, and data points that suggest lower-than-expected inflation are good news. Or, more precisely, data points that the Fed believes suggest higher-than-expected inflation are bad news, and data points that the Fed believes suggest lower-than-expected inflation are good news.

We could be reaching a point where the good news = bad news overwhelms, so that we could come to experience a lot of pain!

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/the-eagle-has-landed

Terrific installment and thoughts