Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 33,000 people who read Apricitas weekly

If you bought or refinanced a home in 2021, count your lucky stars—just two and a half years ago, interest rates on a 30-year mortgage were barely 2.7%. Fast forward to today and they’re consistently around 7%, an almost-unprecedented shift that has brought the gap between mortgage rates for new and existing homeowners to record highs. New buyers are obviously having a much harder time financing home purchases than they did pre-pandemic, with the monthly costs to buy an equivalently-priced home on a 30-year mortgage rising significantly, which in turn has helped drive new single-family housing starts down 25% from pandemic-era peaks. Yet this may cause another structural shift in the housing market—what if higher mortgage rates have turned the low-rate mortgages of 2021 into golden handcuffs, locking owners into their existing homes? After all, who would want to sell their home when doing so means giving up a 3% 30-year fixed mortgage rate and being forced to buy another home at rates exceeding 7%?

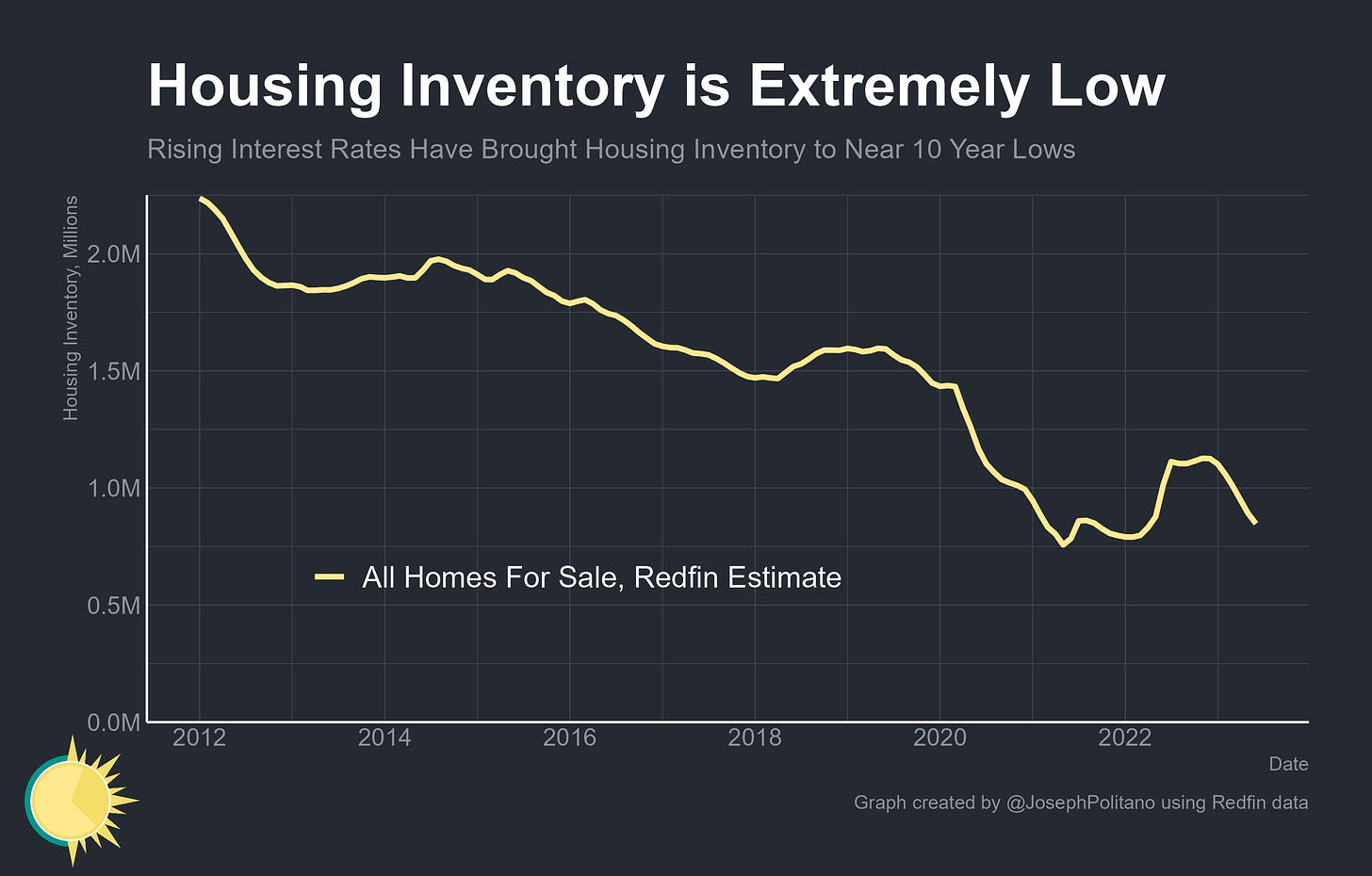

Indeed, listings of homes for sale in the US are down significantly over the last year and are approaching lows not seen since the peak of the wild early-pandemic housing market. If the shift in interest rates has actually locked in existing homeowners, that problem could persist for years—markets simply don’t expect mortgage rates to return to pre-2022 levels anytime soon, implying a long period of depressed housing inventories as owners prolong selling in order to hold onto their cheap debt. Yet this narrative is perhaps lacking a bit of nuance—the effects of lock-in are real, but aren’t the sole driver of the current inventory downturn and likely won’t be as large as they first seem.

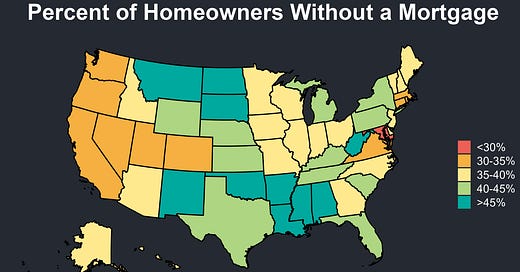

For one, a large share of American homeowners—42%—own their homes free and clear with no mortgage at all, and they are therefore obviously not locked in by prior mortgage rates. Likewise, most existing homeowners with mortgages have large equity cushions by virtue of purchasing before the massive pandemic-era home price appreciation. Excluding people who owned their homes free and clear, the median level of housing debt is only 52% of the value of the home, and those homeowners with large equity cushions should also be less affected by lock-in. Plus, countries like Denmark (where most owners can easily keep their old mortgage when buying a new home) have also seen large dropoffs in available-for-sale housing inventory, as have countries like the UK and Canada where most mortgages reset rates frequently compared to America’s 30-year fixed mortgages.

More importantly, when looking at the county level the fall in for-sale inventory listings shows little relationship to the share of homeowners without mortgage debt. Since June 2021, counties where more homeowners are mortgage-free have seen inventory changes functionally no different than counties where more homeowners would be locked in by rising mortgage rates. Since June 2022 areas with more mortgage-free homeowners have seen larger inventory recoveries, but the overall effect size is still small. If the main driving force behind falling for-sale inventories was mortgage lock-in, we would expect counties where mortgage burdens are higher to show much more substantial inventory declines, yet we don’t.

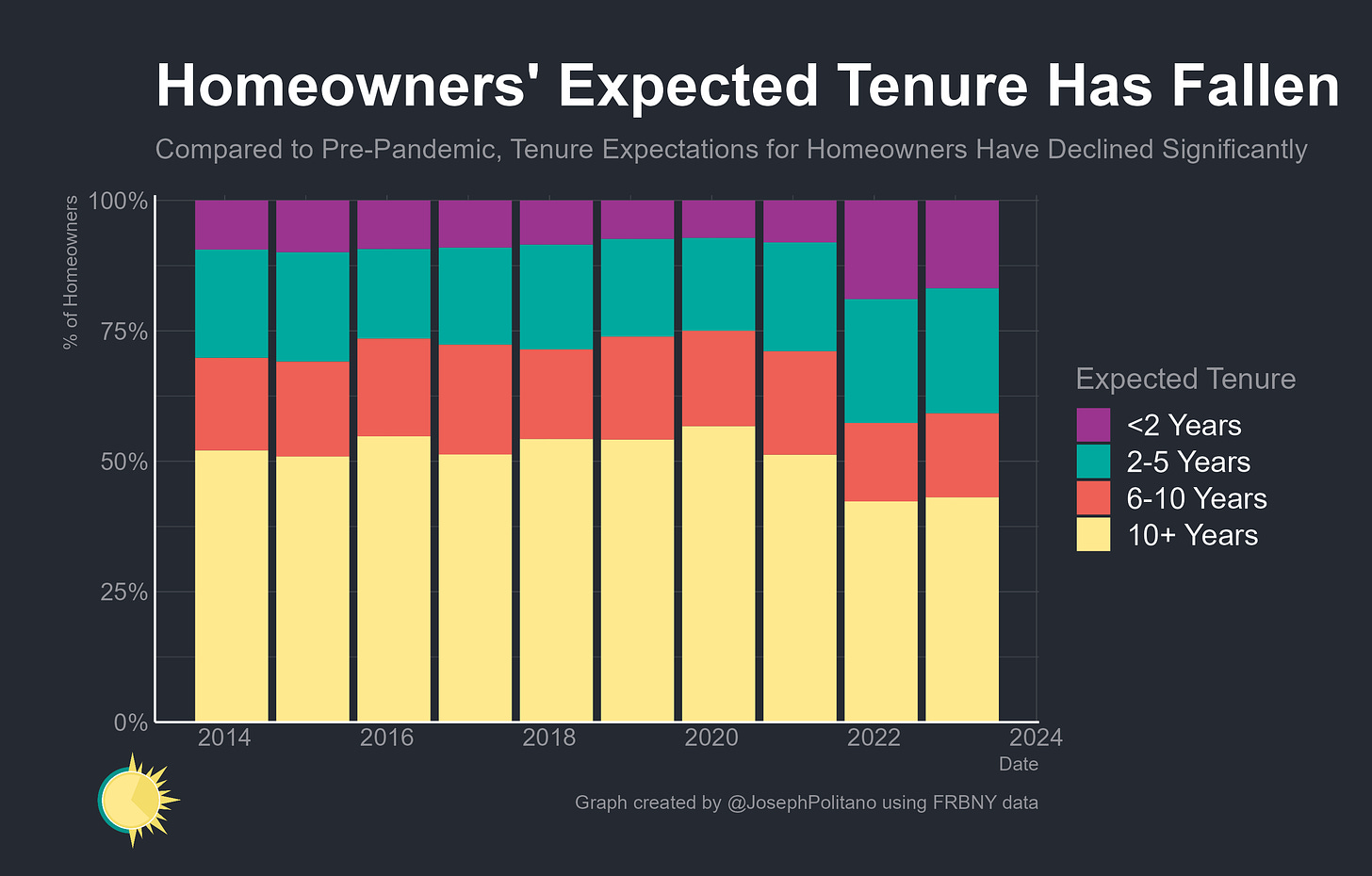

Also, if you wanted to see if American homeowners felt locked in by their low-rate mortgages you could just ask them—and that’s functionally what the Federal Reserve Bank of New York does in an annual housing survey within the broader Survey of Consumer Expectations. In 2022 and 2023, despite much-higher mortgage rates, homeowner tenure expectations were at the lowest levels in the survey’s history. The share of owners expecting to stay in place for more than 6 years fell dramatically, while the share expecting to move in the next 5 years rose—not exactly the behaviors of a population that feels permanently chained to their homes by golden handcuffs. The effects of mortgage rate lock-in are important, as we’ll discuss shortly, but they likely won’t cause the housing market to permanently freeze up—and they are not the sole drivers of today’s low inventory levels. Instead, economic uncertainty and the buyer-side effects of rising mortgage rates are primarily driving short-term inventory shifts, with important implications for future home price dynamics.

Rates, Inventory, Prices, and Housing Uncertainty

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.