How China Suddenly Became a Car Export Powerhouse

Domestic Economic Weakness, Growing Trade with Russia, and an EV Boom Have Sent Chinese Vehicle Exports Surging

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 31,000 people who read Apricitas weekly

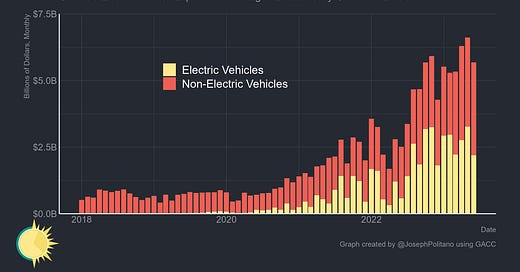

“No one noticed—but we noticed,” said Ford CEO James Farley on an earnings call last month, “something monumental happened in our industry, where China became the number one exporter of vehicles globally. It had always been the Germans or the Japanese.” Indeed, China has long been the world’s largest producer of motor vehicles, but relentless growth in domestic demand, fierce global competition, and the heavily politicized international vehicle trade meant they were a comparatively small player in foreign markets. Yet the country has now burst onto the international scene with unprecedented speed—in 2019, China exported less than 750,000 passenger vehicles in total, which is roughly one-half the number China has exported in only the first 5 months of this year. Perhaps most importantly, China has a substantial technological lead over many of its export competitors, with nearly 450,000 of the cars that it shipped abroad so far this year being electric vehicles and other “new energy vehicles”. Just as successive waves of global industrialization brought companies like Volkswagen, Mitsubishi, Toyota, and more recently Kia and Hyundai into the global consciousness, consumers across the world are becoming increasingly exposed to Chinese automakers like SAIC Motors and BYD.

Yet the situation is not as rosy for China as it first appears. For one, despite the record-setting rise in gross exports and China’s newfound motor vehicle trade surplus, net exports still remain below Japanese and German levels. The per-car value of Chinese vehicles still tends to be lower than their foreign competitors, and a lot of the rise in exports has been matched by a rise in imports. For two, a decent share of the surge is driven by Russia’s inability to construct enough of its own vehicles while under heavy sanctions and its inability to import vehicles from elsewhere in Europe and Asia. Unwillingly and rapidly, Russia has thus been forced into becoming China’s new number-one car customer. For three, as is often the case with China, the strength in export-oriented production is masking weaknesses in domestic consumption—China is not producing significantly more vehicles than it was in 2019, but rather a larger share of its vehicle production is going to foreign rather than domestic consumers. Hence the recent nationwide campaign designed to encourage car purchases and ease up loan terms for domestic buyers. Plus, it is likely competition will stiffen up going forward—carmakers outside China are now recovering from the semiconductor shortage that had hit them disproportionately harder, currently-elevated global car prices are trending downwards as supply slowly catches up with demand, and most importantly countries across the world are aiming industrial policies to directly compete with China’s EV dominance.

Shifting Gears

It is impossible to talk about China's car export boom without first talking about the deepening trade ties between China and its northern neighbor, Russia. When Putin launched the invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, most of the world's major democracies moved to immediately sanction Russia in order to dampen its war-making and economic capabilities. Exports of dual-use goods—inputs that could be used for both civilian and military production—were cut off immediately, doing particularly heavy damage to Russian complex manufacturing that relied on advanced components sourced from abroad. The Russian car industry was among the most obvious targets given how much overlap there can be between military and civilian vehicles and it was among the most vulnerable industries thanks to the complexity of its supply chain.

Sanctions then crushed the Russian car industry—output fell almost 75% in early 2022, a larger hit than the onset of COVID, and has struggled to return to half of pre-invasion levels. In this environment, China has moved, cautiously and opportunistically, to fill the gap left by Russian manufacturing’s weakness. Chinese vehicle exports to Russia initially contracted in the immediate aftermath of the sanctions, but once the shock wore off and geopolitical uncertainty from the Chinese government vanished, exports came roaring back and surged to 4.5 times pre-invasion levels. In the month of June alone, more than one billion dollars worth of Chinese vehicles were exported to Russia, a nearly 54 times increase from June 2018 levels

Yet while Russia is far and away the largest single-nation source for China’s new vehicle exports, it represents just a fraction of the trade expansion seen during the pandemic. The largest aggregate importer of Chinese vehicles is the European Union (including the UK), which is responsible for roughly one-third of the total export volume. Here, China’s electric vehicle presence is especially important. Outside of the EU and UK, a fairly wide array of states across the Middle East, Oceania, North America, and elsewhere in Asia make up the bulk of destinations for remaining Chinese vehicle exports.

However, a key element of this export boom is that China is not actually producing substantially more vehicles than it was before the pandemic. In fact, output remains slightly down compared to peak levels in 2018/2019—the rise in exports over the last few years has occurred simultaneously with a decline and subsequent stagnation in aggregate output. China is thus using strength in export-oriented sectors to partly cover for the ongoing weakness in domestic consumption post-lockdowns, and at the same time looking to finally bring its strong domestic electric vehicle industry to bear in international markets.

China’s Domestic Demand Crunch & The EV Revolution

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.