How Europe is Decoupling From Russian Energy

Russian Natural Gas Exports to the EU are Down Nearly 90%—but the EU has Been Able to Replace Russian Supplies with Record Liquefied Natural Gas Imports

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 21,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

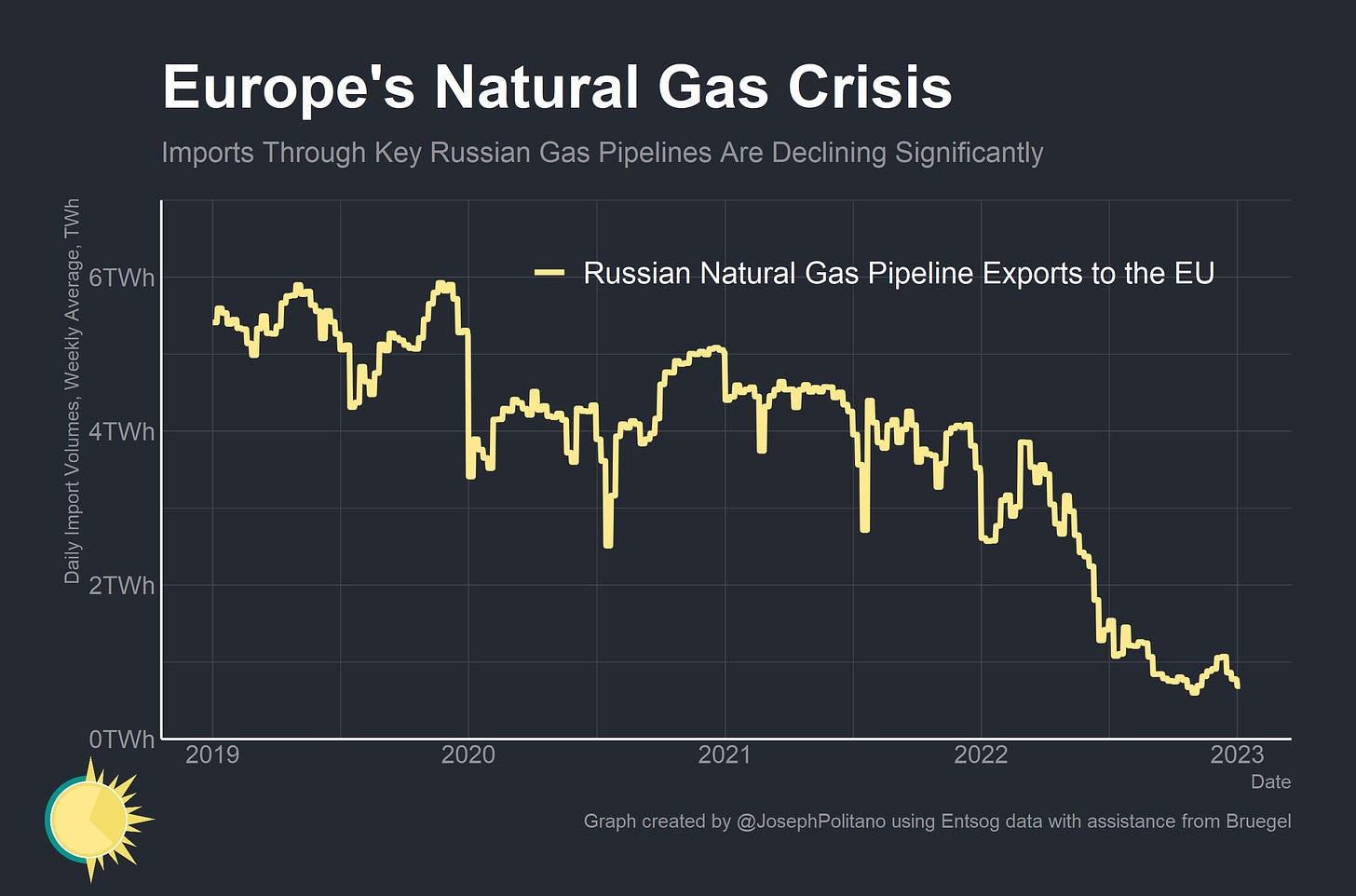

The European energy shortage was already acute before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine nearly one year ago—and the invasion itself turned a bad situation into a crisis. European countries depended on Russian energy products, especially natural gas, for their basic economic health and welfare, hence why energy was largely excluded from the original sanctions against Russia. Then, as the country’s military offensive in Ukraine began deteriorating, Russia began drastically reducing the amount of natural gas it sent to Europe in a bid to inflict economic pain on its foes and to gain the leverage necessary to reduce EU support for Ukraine. Today, the EU is being forced to decouple from Russian energy as gas exports to the EU have fallen by nearly 90% compared to pre-pandemic levels.

However, thanks to a rapid buildout of liquefied natural gas capacity, new sources of energy imports, reduced consumption, and fortuitously warm weather, the EU has significantly improved its energy outlook since this summer—and the worst possibilities for this winter look to have been avoided. The energy crisis is still a significant drag on European growth and a massive contributor to inflation, and markets still anticipate elevated natural gas prices until 2026, but the situation now poses less of an existential risk. Critically, European economies have been able to buy themselves more time—the most valuable resource in their efforts to become independent of Russian energy.

Replacing Russia

Before 2022, Germany received more than 150 million cubic meters per day of Russian natural gas from the Nord Stream pipeline and had no capacity to import any seaborne liquefied natural gas (LNG). Today, the opposite is true: nothing flows through the Nord Stream pipeline after its apparent sabotage earlier this year, but Germany has just started importing LNG through the newly built terminal at Wilhelmshaven and has more LNG import capacity on the way.

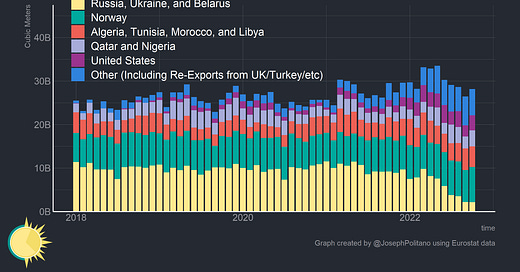

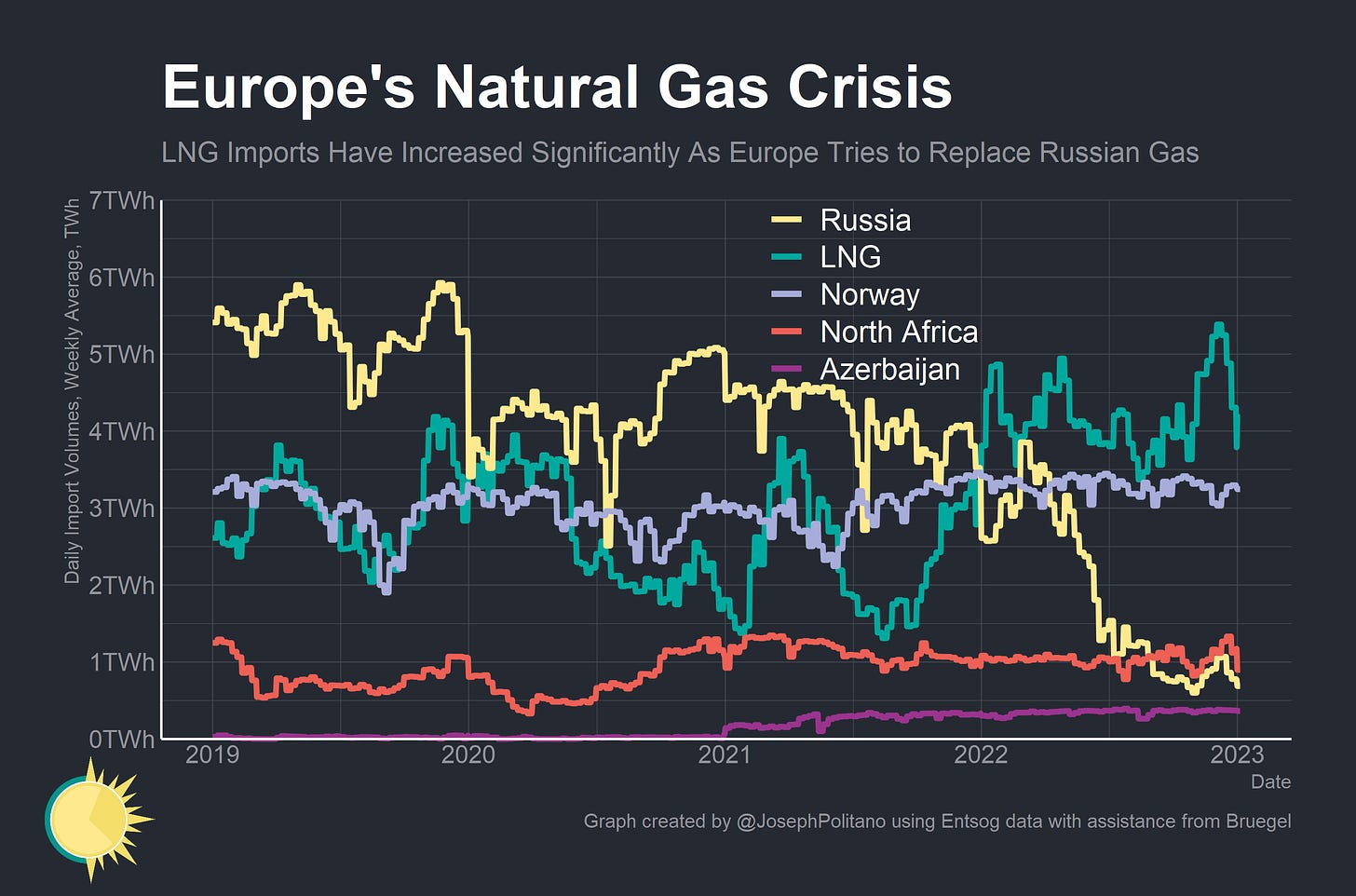

The trend is the same across the continent—Europe (in the above chart, including the UK) has been able to replace practically all of the lost Russian energy imports by drawing record amounts from global LNG markets and getting some assistance through rising pipeline imports from Norway, North Africa, and other areas.

The rise in LNG imports means that the EU still imports essentially as much natural gas as it did before the invasion of Ukraine—it’s just that much, much less of it comes from Russia. Norway has now become the bloc’s new largest source of natural gas—and North Africa now supplies more than Russia in aggregate.

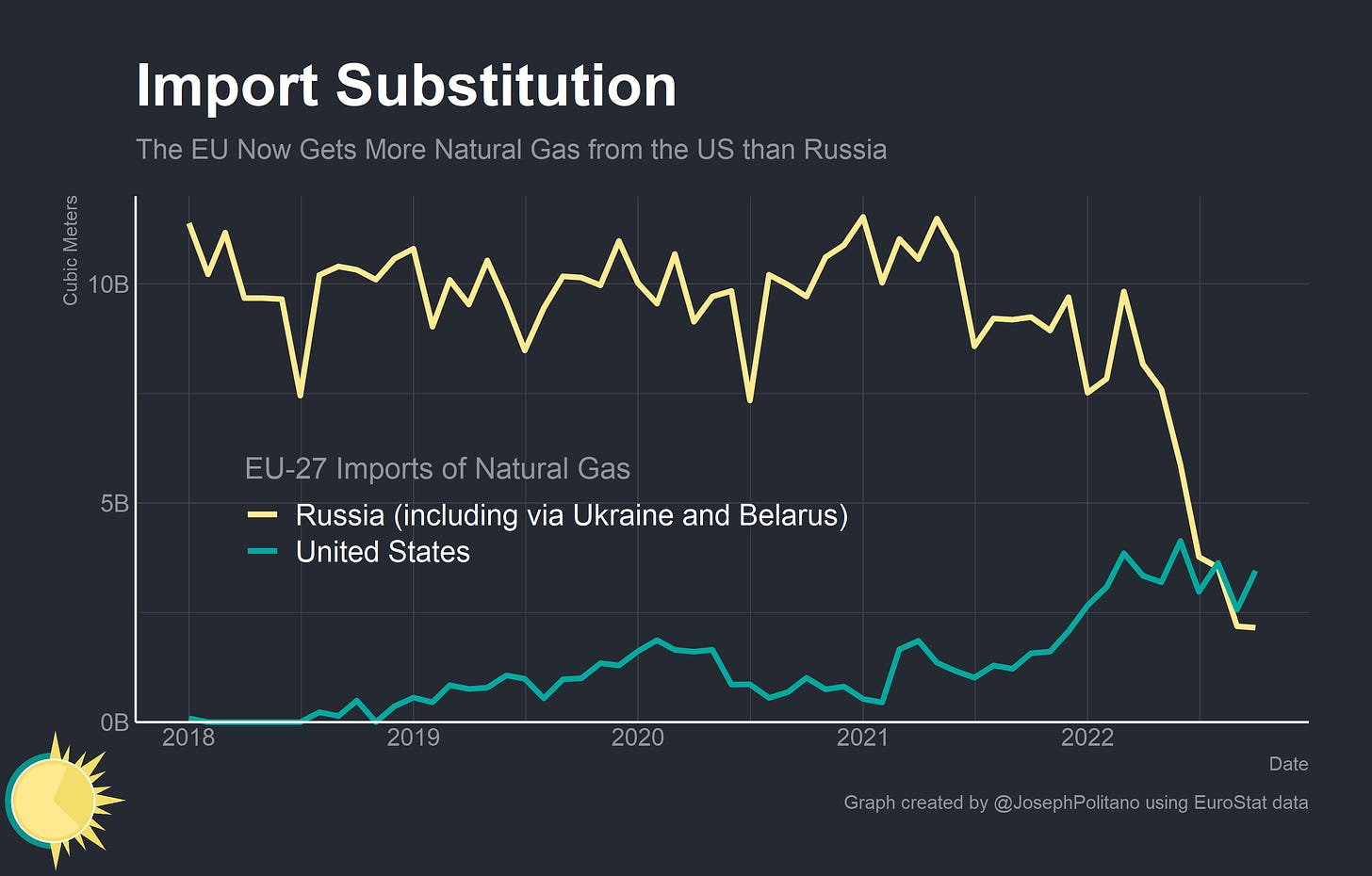

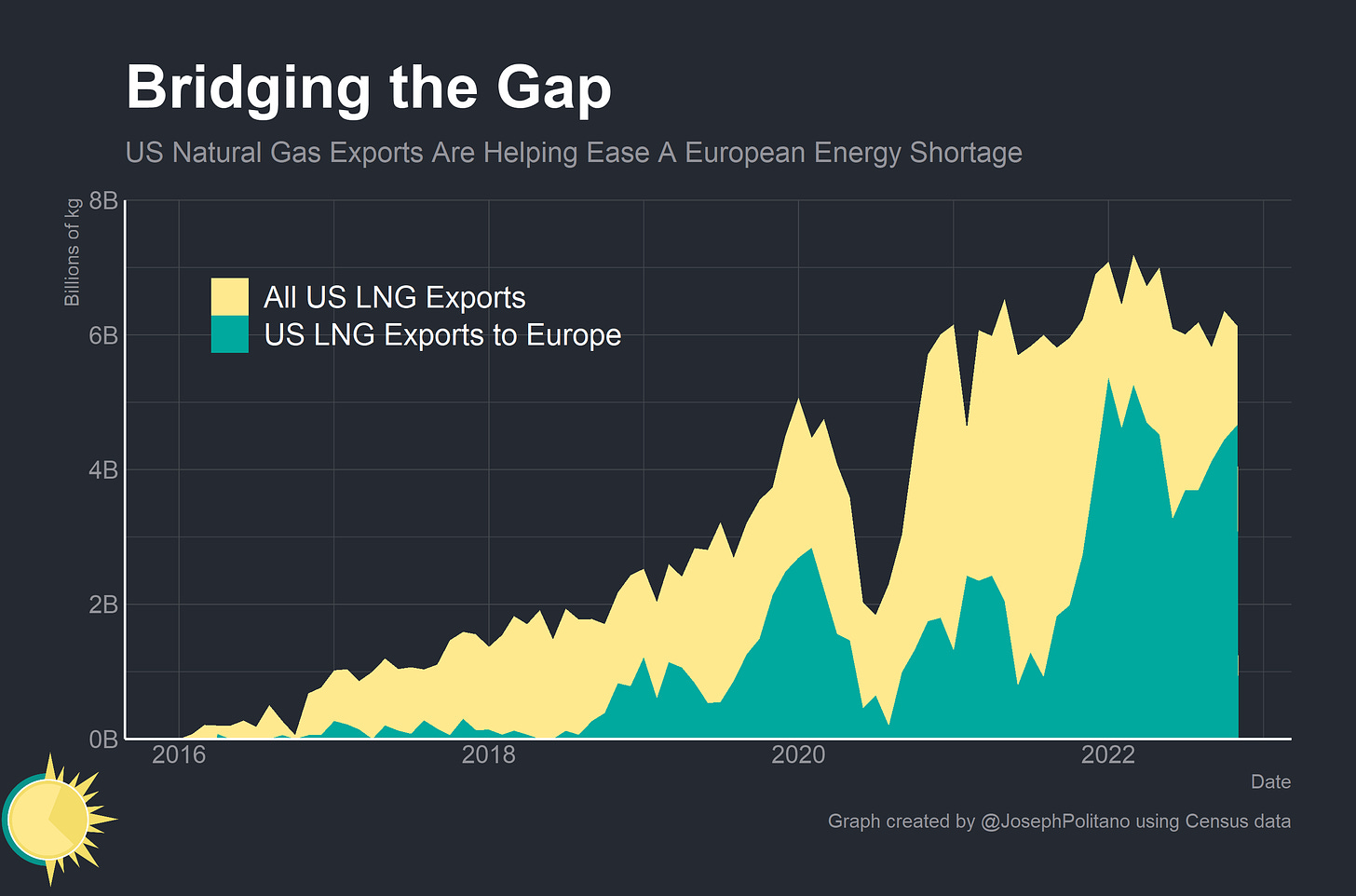

In fact, the massive buildout of US LNG export capacity (America become the world’s number one LNG exporter earlier this year) combined with the total collapse in Russian natural gas supplies to Europe has meant that the EU now gets more gas from the US than the Russian Federation. In Euro terms, the EU now actually imports slightly more total energy (including oil, petroleum products, coal, etc) from the US than Russia.

Barring a rapid about-face in Russian energy politics, this gap will likely only continue to grow—American LNG export capacity is expected to increase in 2023, especially as the Freeport LNG facility in Texas recovers from its accident last year, and the EU already banned further imports of Russian crude just over a month ago.

More recent data shows the amount of American LNG exports destined for European shores has been increasing recently—and that shipments to Europe continue to make up the vast majority of US LNG exports. At the onset of the Russian invasion, European economies got lucky that China was entering a period of strict lockdowns and thereby depressing global energy demand at a time when Russian energy supplies were rapidly going offline. Today, however, China’s economy is reopening—intensifying the competition for the world’s limited-but-growing LNG capacity. Instead, after a period of intense planning in order to refill gas storage tanks for this winter, European economies are getting lucky in a different way—with historically warm weather.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.