How High Will Interest Rates Go?

Mapping the Shifting Relationship Between Rates, Financial Conditions, and Inflation

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 17,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Earlier this week, the Federal Reserve again voted to raise interest rates by 0.75%—its fourth consecutive historically-large hike. Inflation remains at the forefront of US monetary policy decisions and it’s inflation that solidified the FOMC’s push to continue its rapid pace of rate hikes. With interest rates rising so quickly, the big question remains—how high will they go?

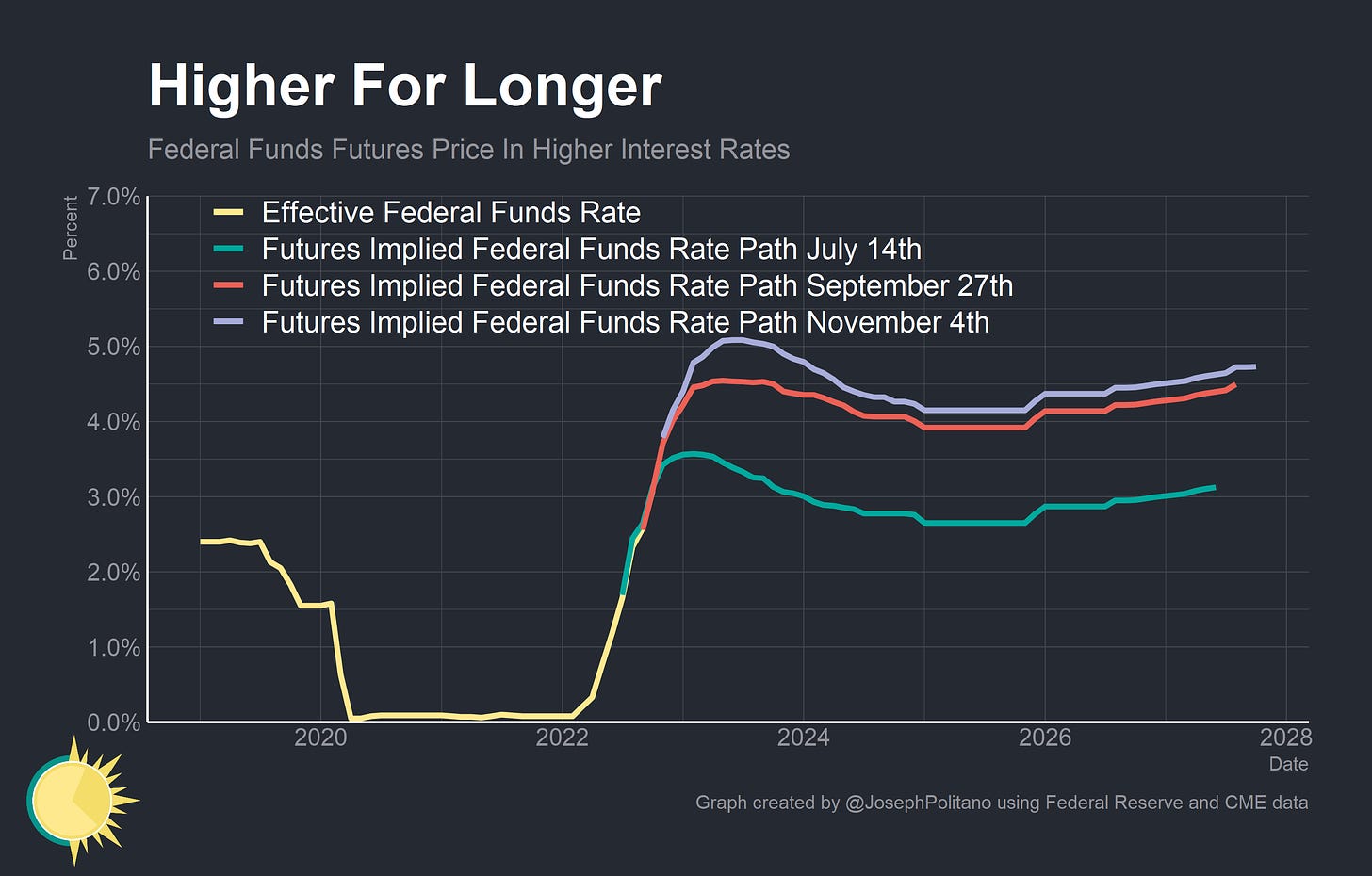

Right now, futures markets expect short-term interest rates to peak at around 5% in mid-2023 before declining to about 4% by 2025 and then hovering between 4-5% for the next few years. That’s markedly higher than estimates for peak interest rates just four short months ago—and a world away from the 1.5% forecasted for mid-2023 at the start of this year. 30-year fixed mortgage rates are at nearly 7% for the first time in 20 years, 10-year yields are above 4% for the first time since the financial crisis, and short-term interest rates are already at the highest level in more than a decade. So how have interest rates moved so fast in such a short time after being stuck near 0% for years? The answer lies partially within the shifting relationship between rates, financial conditions, and inflation.

Interest Rates Aren’t Indicative of the Stance of Monetary Policy

Interest rates are a monetary policy tool and a central bank target, but they aren’t ipso facto the stance of monetary policy. At different times and under different conditions, the same interest rate policy can produce wildly different outcomes—and it is the relationship between interest rates and these outcomes that best encapsulates the true stance of monetary policy.

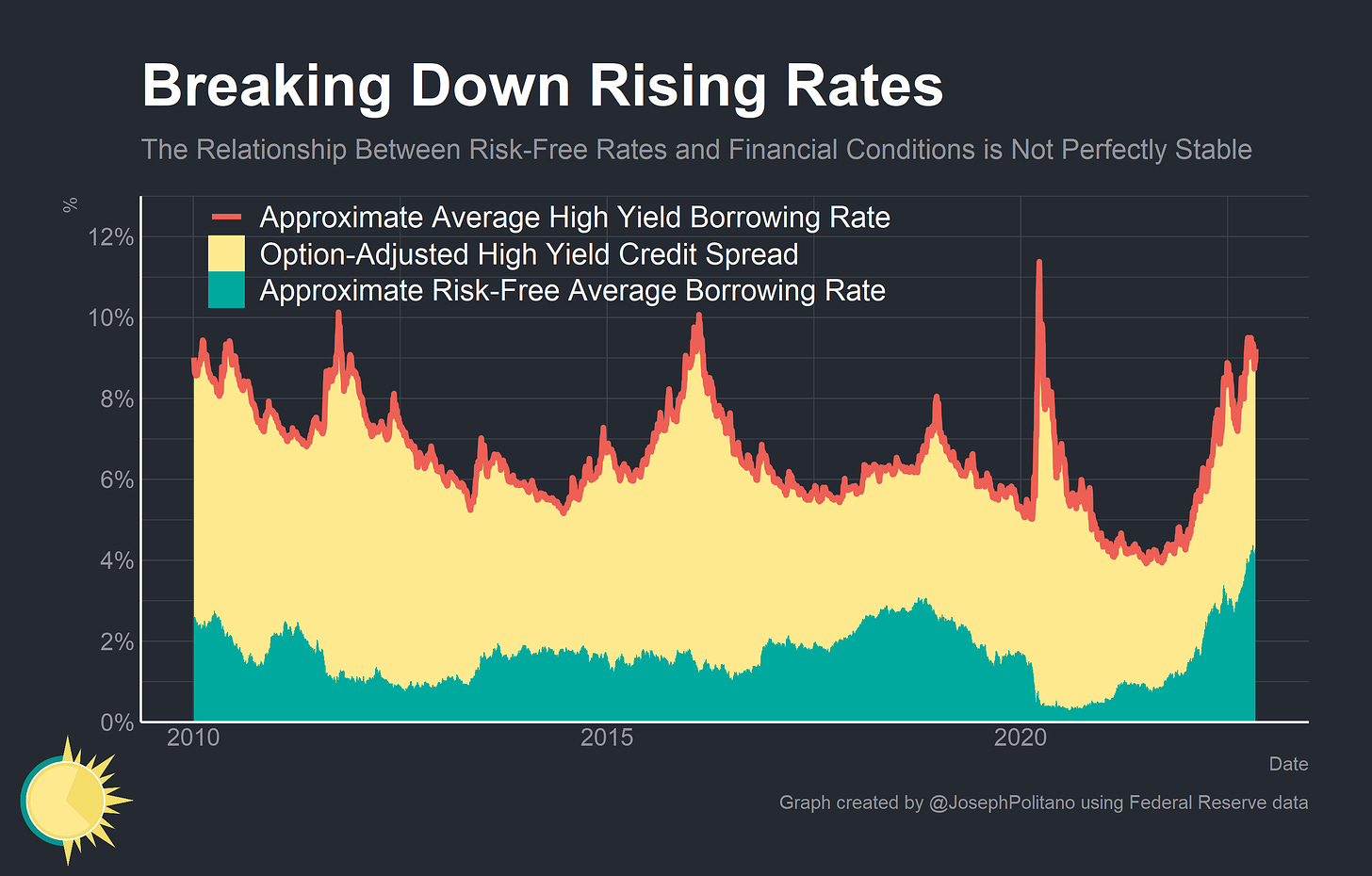

Decomposing corporate borrowing costs into an average risk-free rate and a credit spread component helps to illustrate this. Over the last year, rising interest rates have dramatically increased the average risk-free borrowing rate far above anything we’ve seen over the last decade. That, in turn, has increased high-yield credit spreads—the premium riskier corporate borrowers must offer to borrow money, which proxies as a critical measure of financial conditions. In other words, rising rates have worsened financial conditions—but the relationship between risk-free rates and financial conditions has been anything but stable over time. Today’s higher rates are producing relatively worse conditions than during the 2018-2019 tightening cycle, but relatively better ones than the 2012/2016 cycles. Lower rates in 2012/2016 were comparably tight, and higher rates today are comparably loose once you account for the relative state of the economy across time.

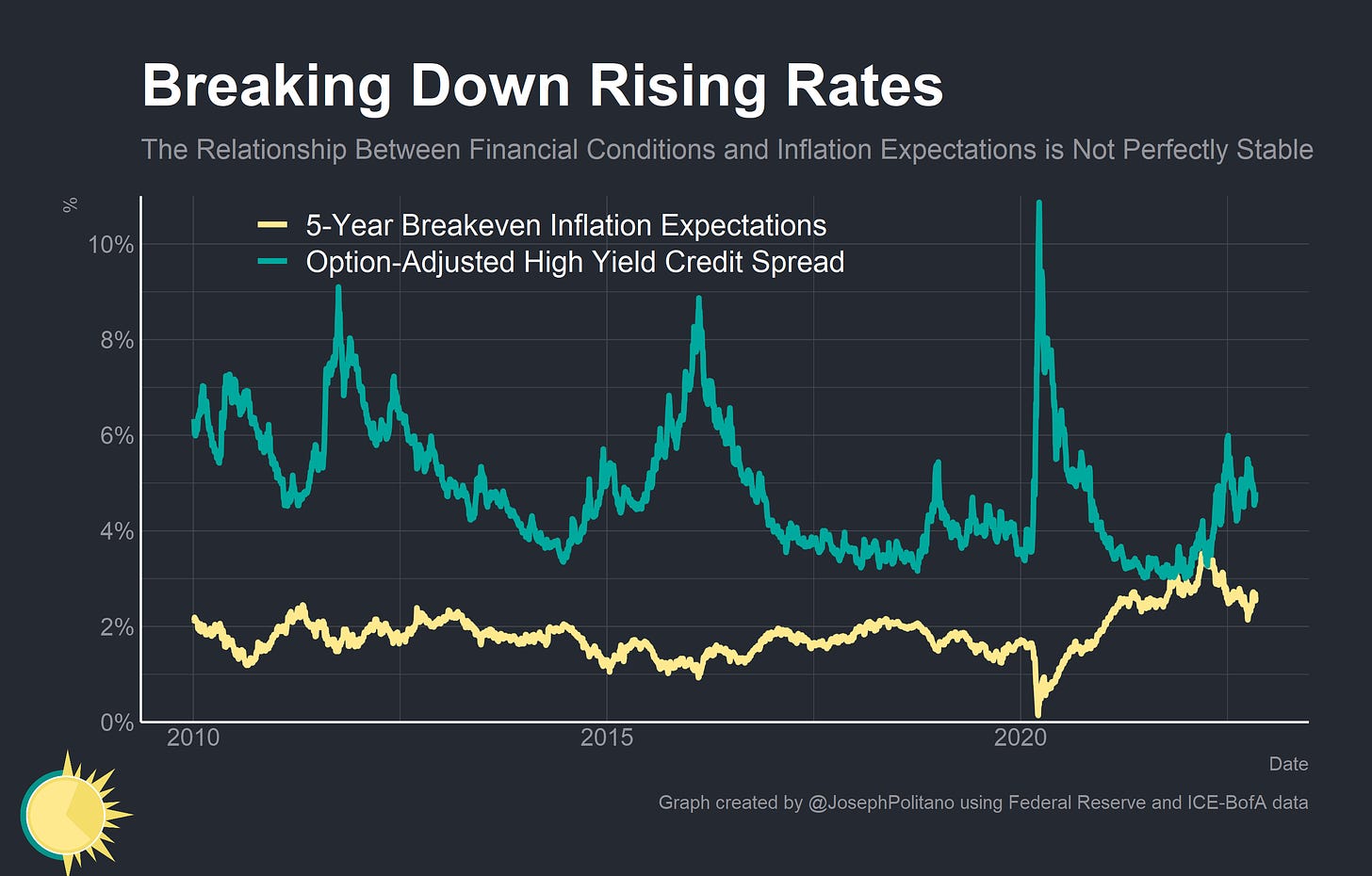

The relationship between financial conditions and monetary policy target variables—importantly, inflation—is also not stable over time. The rapid worsening of financial conditions has produced lower inflation expectations—but inflation expectations remain higher today than at any point in the 2010s. The worsening of financial conditions in the 2018/2019 hiking cycle managed to pull inflation expectations well below any number consistent with the Federal Reserve’s 2% target, but the comparatively larger worsening of financial conditions today has only just managed to bring inflation expectations to target-consistent levels.

Over the last year, we have seen financial conditions worsen significantly as the Fed raised rates to 3.75%—but conditions worsened more than when the Fed raised rates to 2.25% in 2019 and less than when the Fed merely started signaling tighter policy in 2015/2016. By the same token, today’s tighter financial conditions have not yet had the same effect on inflation or real economic variables as they had during the 2019 or 2015 tightening cycles. Interest rates must be evaluated against their impacts on real economic variables to determine the stance of monetary policy, and policy is arguably looser today than during the 2010s despite nominally higher interest rates.

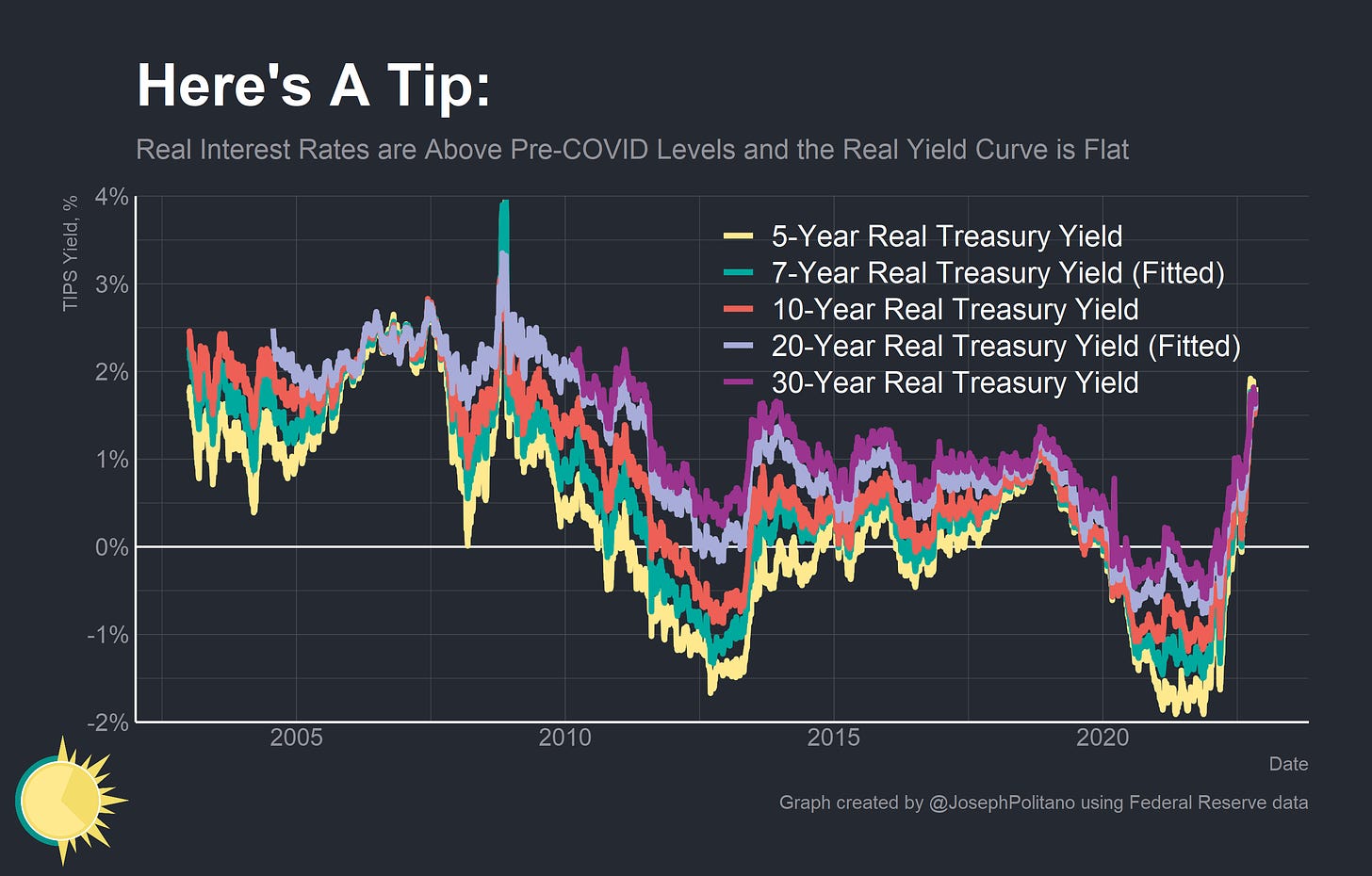

This is where another important counterintuitive insight comes into play—high interest rates are usually a sign that monetary policy was too loose in the recent past and low interest rates are usually a sign that monetary policy was too tight in the recent past. Most people characterize the zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) era of the 2010s as “easy money”, but relative to the extreme credit crunch of the Global Financial Crisis and the weak employment, nominal growth, and inflation of the time monetary policy was actually too tight. Conversely, the rapid real economic recovery and the large bout of inflation we’ve recently experienced made 0% interest rates far too loose and has since pushed both real and nominal interest rates much higher. Compared to before the pandemic, both five-year real interest rates and 5-year inflation expectations are significantly higher, leading to an almost 2% rise in nominal 5-year treasury yields. Higher nominal interest rates represent, in effect, monetary policy chasing after rising inflation.

Getting Real

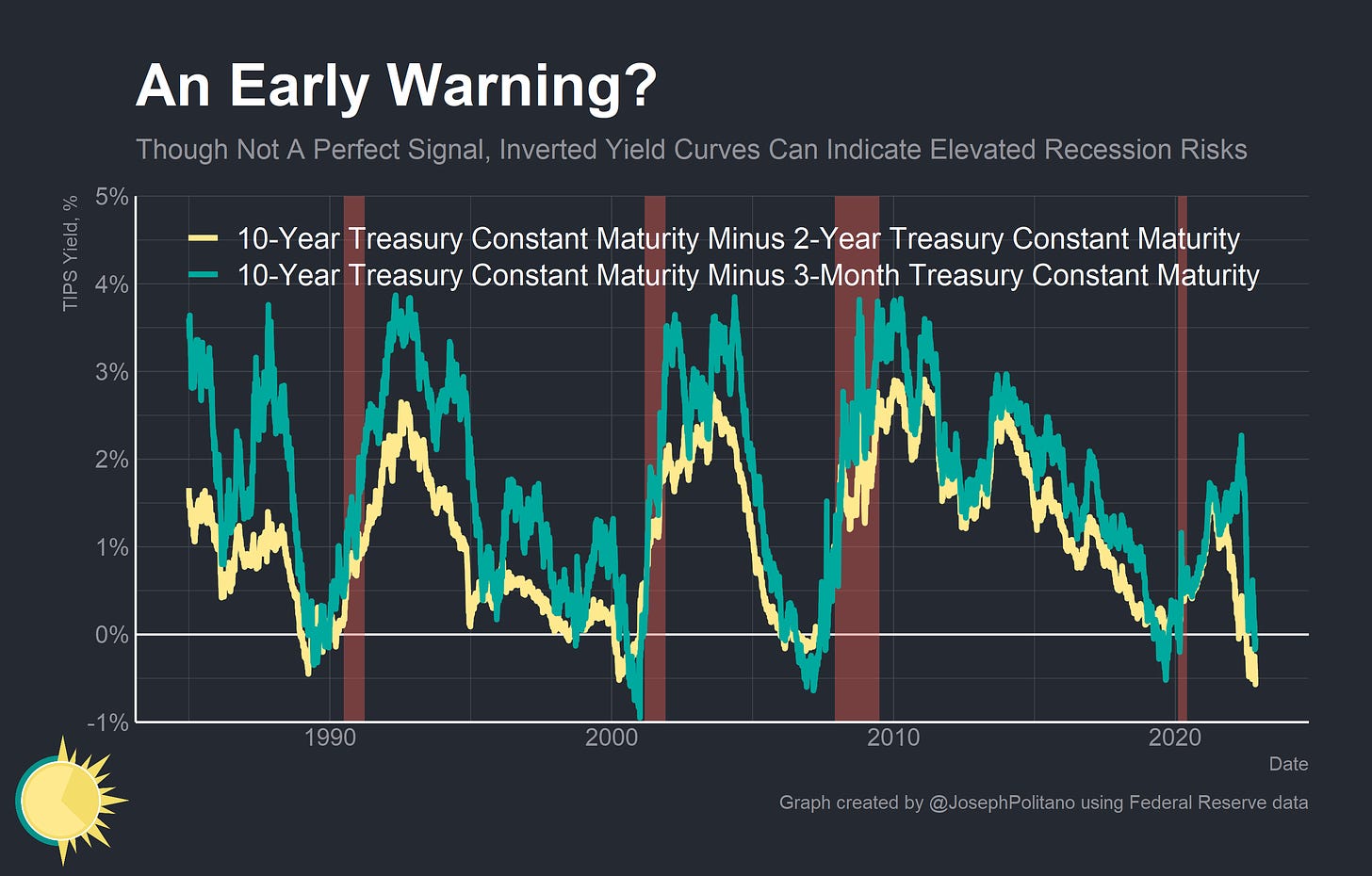

I don’t want to completely overstate this case, however. Today’s higher interest rates are clearly having real macroeconomic effects and are a large portion of why recession risks are elevated. The yield curve is significantly inverted which, although it by no means guarantees a recession, does still suggest that market participants expect rate cuts in the near future and are increasingly fearful about the short-term economic outlook.

By historical standards, it is absolutely incredible that such low interest rates could produce such large recession fears amidst such high inflation. Various specifications of the Taylor rule, a simple but popular monetary policy model that sets interest rates based on inflation and estimates of potential output, would suggest interest rates of between 6.5-8% are necessary to stop inflation. Instead, peak rates of just about 5% and real 5-year interest rates of less than 2% are threatening to topple the US economy.

It’s a good reminder that despite today’s inflationary troubles many of the structural forces causing the long-run decline in real interest rates still persist. Wealth inequality is still high, working-age population growth is still low, productivity growth is still weak, and global populations continue to age, all of which have likely put downward pressure on interest rates over the last few decades. The main change pushing up real interest rates is the move from the structurally weak demand environment of the 2010s to the structurally strong demand environment we find ourselves in today—and it is the relative importance of this shift on appropriate monetary policy that the Federal Reserve has had an extremely difficult time estimating.

Conclusions

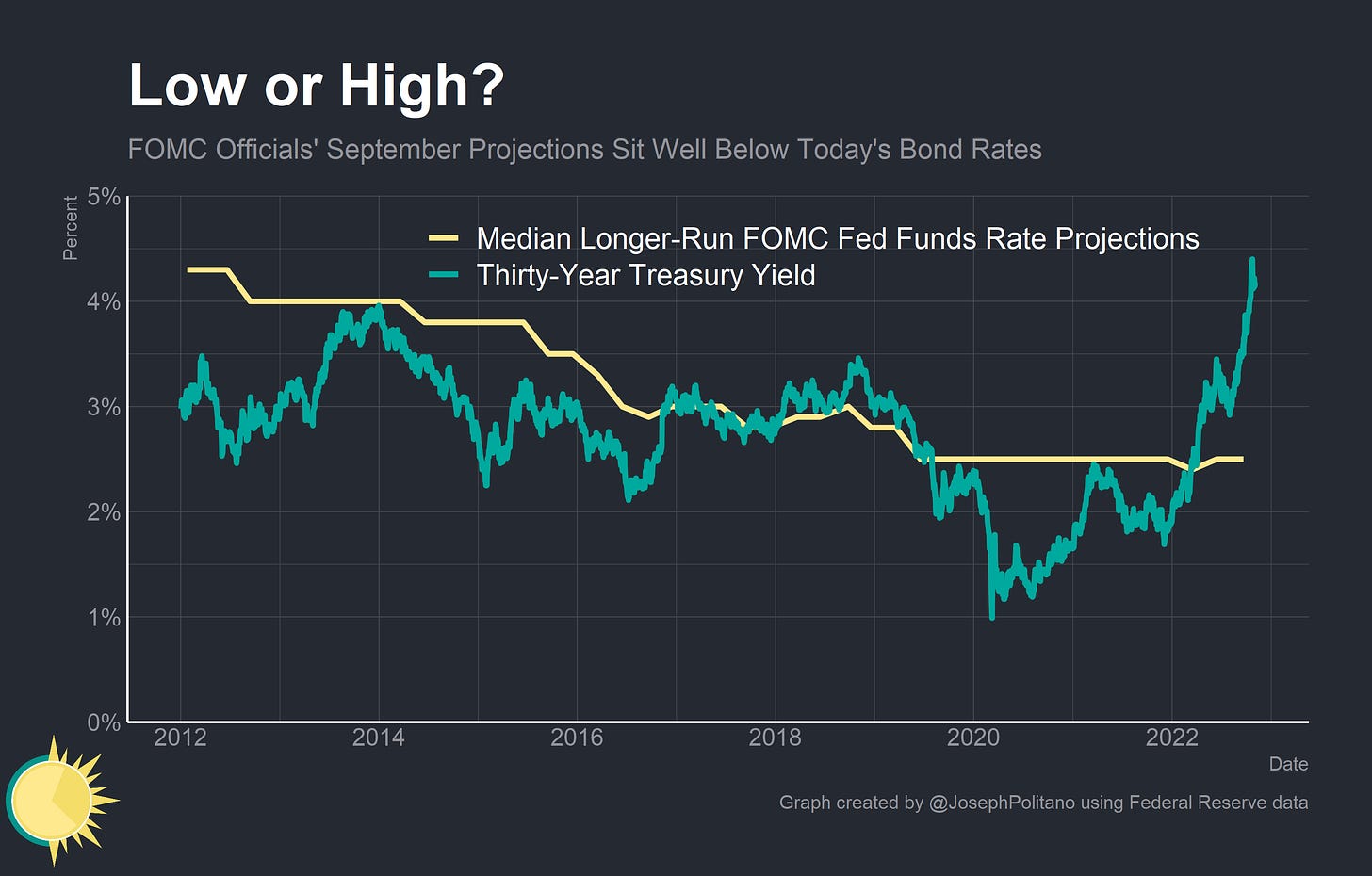

How high interest rates get will depend in large part on how long the comparatively strong economic environment persists. In September, Jerome Powell and the rest of the Federal Open Market Committee believed long-run interest rates would stabilize around the 2.5% mark—which is now significantly below long-run treasury yields. In other words, markets are less worried about an immediate return to the ZIRP era of the 2010s and are pricing in increasingly high long-term interest rates. However, they still don’t yet see anything that would fully break us out of our historically low global rate environment—yields on the Austrian 100-year bond may have increased 1.5% over the last year but still remain just below 2.4%. Interest rate uncertainty, though, remains extremely high—unfortunately, nobody seems to know just how high interest rates can go.

Another technical but accessible article.

A suggestion for the decline in productivity, in the UK, is early retirement.

Beautiful article! I love these charts so much I'm curious to know what your tech stack looks like to make them as customizable as I assume they are?