How the Banking System Changed Post-SVB

How the American Banking Industry is Being Forced to Adapt After This Year's Crisis

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 29,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

It has now been nearly three months since the death of Silicon Valley Bank, then the second-largest bank failure in American history. Two other US banks—Signature and First Republic—collapsed in its wake, and the remains of all three have now been sold off by the FDIC. Several more regional banks have come under pressure in the wake of this year’s banking crisis, with those reliant on uninsured deposits and overexposed to long-term assets disproportionately at risk as depositors rapidly became more sensitive to their banks’ finances.

However, we now seem to be settling into a post-SVB normal, with some of the near-term risks subsiding and the finance industry steadily adapting—and critically, we now have enough comprehensive banking data to examine how institutions responded to this year’s banking crisis. Broadly, mid-size and smaller regional banking institutions have been forced to rely less on uninsured deposits and cheap savings deposits for their funding. Instead, they must choose between expensive options like time deposits or (as in most cases) increased borrowing in order to fund their assets. Deposit levels at the country’s megabanks have stabilized, as large inflows from regional banks counterbalanced previous outflow trends caused by rising rates, although the evidence suggests they are more sanguine about allowing their deposit levels to shrink rather than pay higher overall rates to depositors. Banks have moved away from both uninsured deposits and long-term assets, and the perceived risks of uninsured deposits may have also decreased marginally as the immediate crisis is further and further behind us. Perhaps most importantly, the crisis has made banks even more pessimistic about the US economy, with the vast majority further tightening credit availability and remaining wary about the possibility of an upcoming recession.

Flight to Safety

The aggregate level of deposits fell by more than $470B between January 1st and the end of March, with total uninsured deposits falling at an extremely rapid pace. Uninsured deposits outside of the nation’s “too-big-to-fail” Global Systemically Important Banks fell by more than $530B, and that is before accounting for the failure of First Republic and its subsequent sale to JPMorgan Chase in May. The end result is a marginally safer aggregate deposit base—only 17.5% of all deposits are now uninsured outside GSIBs—but one that is significantly smaller—the aggregate decline in deposits has been nearly 1.2T over the last year.

That aggregate deposit decline has been almost entirely the result of outflows from saving, money market, and other non-demand deposit accounts. This is transparently a byproduct of the rising interest rates over the last year—given the rapid increase in rates, short-term risk-free government bonds now pay more than 5% while savings accounts pay a national average of only 0.39%. Banks adjust rates to balance using their relationship with customers to take advantage of low-cost funding or raising rates to keep deposits secure—and institutions have consistently leaned towards taking advantage of low-cost funding, meaning deposit rates are rising slowly relative to headline interest rates and yield-hunting depositors usually need to withdraw deposits if they want a better deal.

Banks experiencing acute, unexpected deposit outflows have relied more on expensive borrowings for their funding needs—especially in the immediate wake of SVB’s failure. Borrowings at large domestic banks (those in the top-25, so including what many would consider “mid-sized” banks alongside GSIBs) are up $265B from March 1st, and borrowings and small domestic banks are up $145B over the same time period. Advances from the Federal Home Loan Banks, institutions that act as lenders of next-to-last resort to the banking system, rose by more than $220B in Q1, with the FHLBs’ total assets creeping above $1.5T.

Borrowings have eased up as the immediate crisis has passed, especially in small banks where they retreated significantly from their record highs, but remain highly elevated compared to COVID-era norms. That rising dependence on borrowing is a major cost to banks, especially when the short-term rates they are borrowing at are so much higher than the deposit rates they replaced (and higher than current safe longer-term yields).

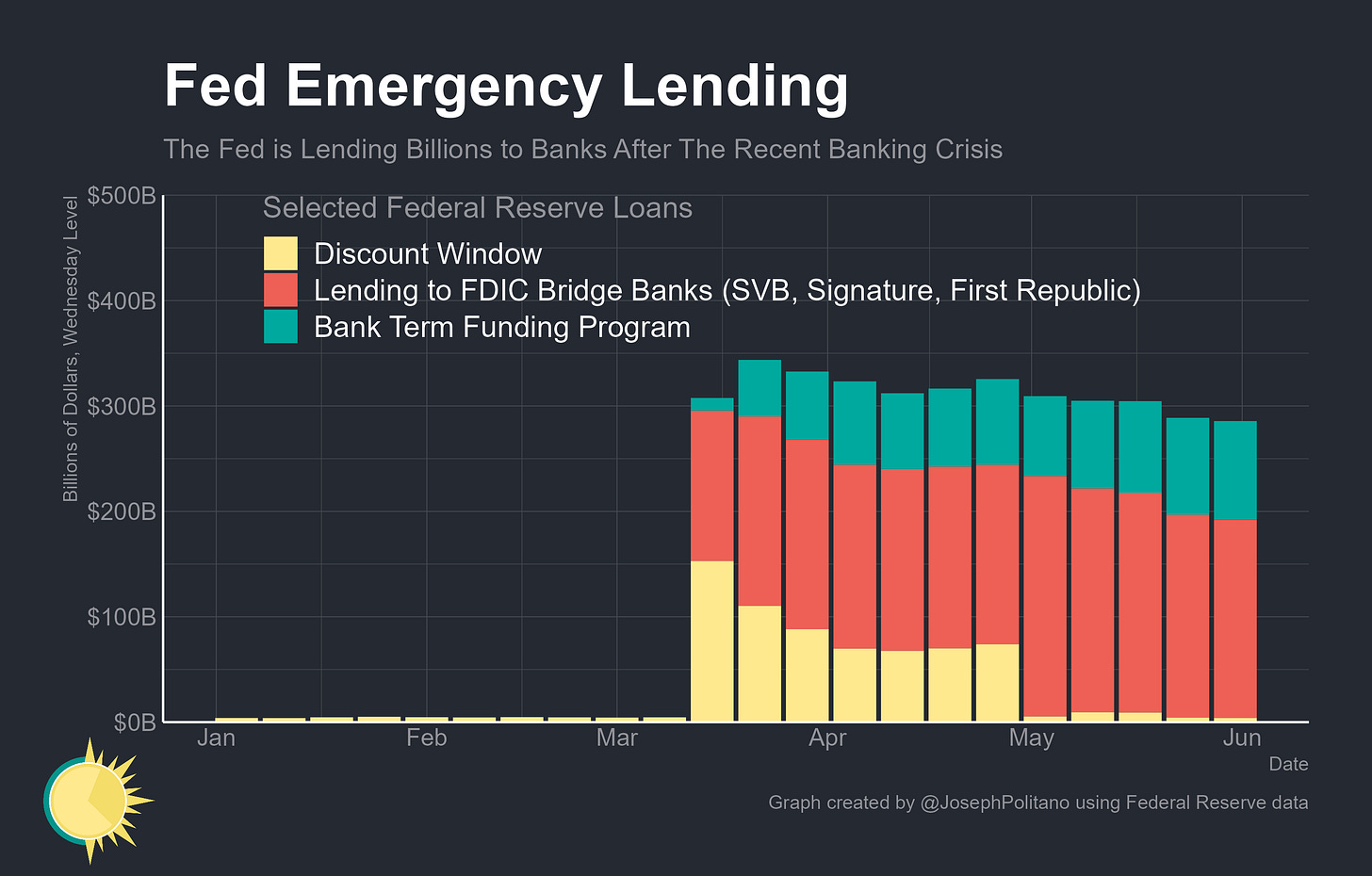

Importantly, the Federal Reserve’s lending to the banking system has also declined significantly in the months since the failure of SVB. Discount window lending, which is the most direct short-term credit provided to banks, has essentially returned to pre-crisis lows after the failure of First Republic (which was the biggest single user). The Bank Term Funding Program, which was designed to alleviate concerns about long-term assets with unrealized losses by lending generously against safe collateral at par for extended terms, has $93B in total outstanding—but that level has only increased by $10B in the last month. The biggest line-item increase has been lending to the FDIC as they manage SVB, Signature, and First Republic’s remaining assets.

Still, in the months since the collapse of SVB aggregate deposits in the banking system have restabilized—resuming their steady decline as intended by the Federal Reserve’s efforts to tighten monetary policy and shrink their balance sheet. Notably, most of the deposit losses since 2022 have been concentrated in larger firms, with the one exception being the massive level shift that occurred precisely when SVB and Signature banks failed. Since then, deposits at small banks have been relatively constant.

Fighting Risks

This stabilization has helped US bank stocks rally comparatively from their May lows—although the vast majority of financial institutions still have cumulative returns well below the broader stock market this year, the relative center of the distribution return has risen from roughly -35% to roughly -25% over the past month. That recovery has also been propelled by the alleviation of risks that continue to hold back the banking sector.

Aggregate losses on banks’ portfolios of Mortgage Backed Securities, Treasuries, and other securities—the kind of losses that helped bring down Silicon Valley Bank—declined for the second straight quarter as banks’ portfolios slowly matured and longer-term interest rates sank. At roughly $515B, aggregate securities losses now represent roughly 2.2% of banks’ total assets.

Expanding from the narrow focus on securities to looking at long-term securities more broadly, we can see little overall movement, although system-wide long-term assets sunk by roughly $36B in total.

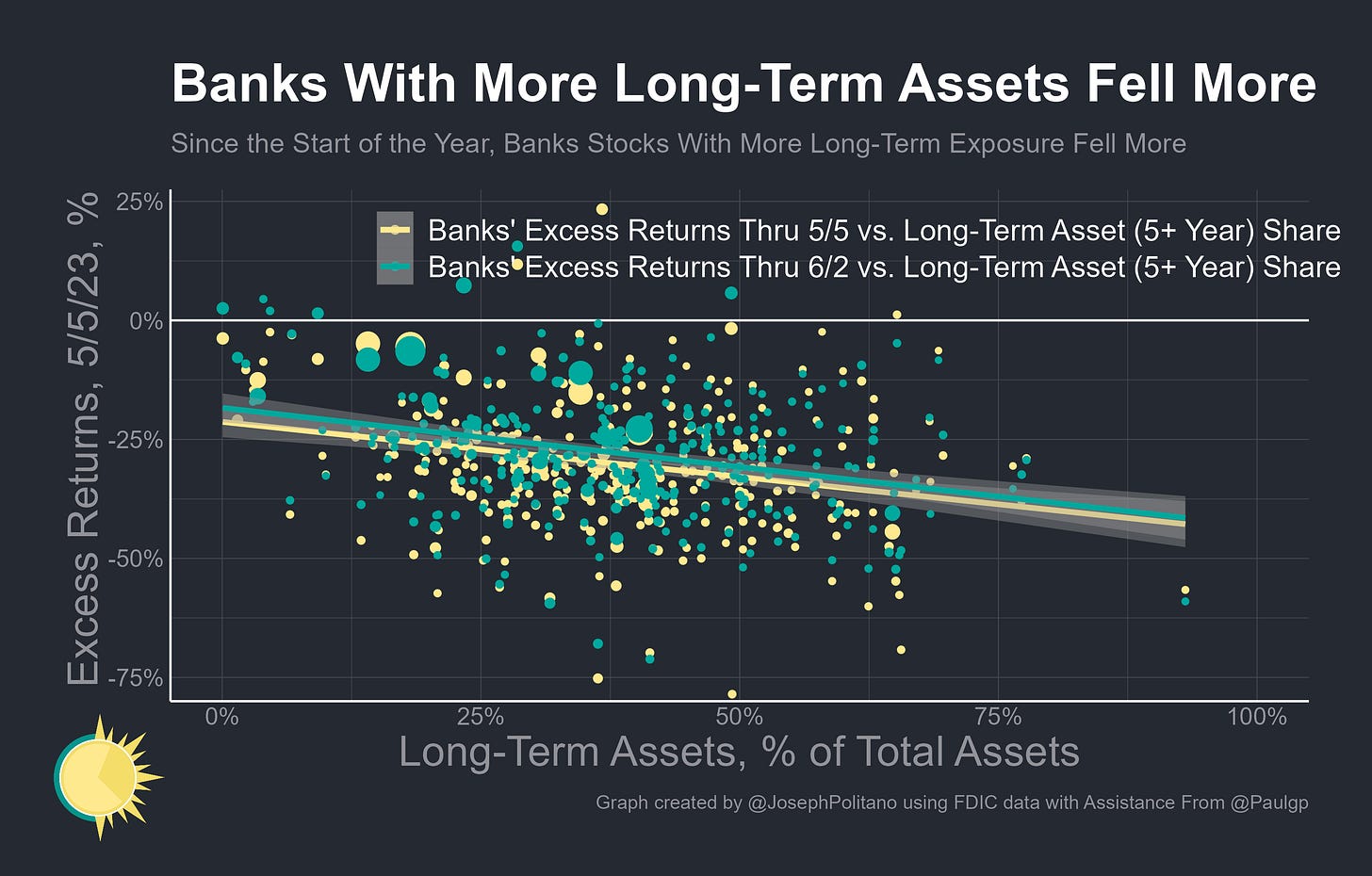

However, it’s important to note, there has been extremely little shift in the relationship between banks’ concentration in long-term assets (particularly real estate assets) and their excess returns that I observed in my prior piece on risks in the banking system. By and large, institutions with more exposure to long-term assets have seen disproportionately worse returns, and that pattern has not changed since May.

On the flip side, there may be inklings of a repricing of the risk of uninsured deposits. Institutions with more reliance on uninsured deposits have recovered marginally more than those with less over the last month, as seen in the chart above, although the effect is small enough that it’s far too early to determine if it’s anything more than random noise. In other words, funding from uninsured deposits is definitely perceived as riskier than at the start of this year, but it might be perceived as slightly less-risky than at this time last month.

Indeed, shares in the at-risk major regional banks I previously focused on have all at least partially recovered since the failure of First Republic, with Western Alliance Bank in particular essentially returning to late-April prices. Those share price declines have still had profound effects on banks’ behavior though, with institutions like Pacific Western forced to sell off real estate loans in order to recover, and that is resulting in a profound reduction in willingness to lend among banks.

Tighter for Longer

The deteriorating macro environment, relative lack of liquidity, and elevated financial risks have caused American banks to further tighten lending standards and credit availability in the wake of SVB’s collapse. That’s true for both business and household loans, where banks are tightening at levels not seen since the 2008 Recession or the initial COVID pandemic.

The major reason banks are tightening lending standards? Renewed pessimism about the current economic outlook. When asked in the Fed’s recent senior loan officer survey, nearly all banks said that the deteriorating economic outlook was a somewhat or very important reason for their decision to curb credit availability.

Yet the same survey showed smaller banks facing a different, acute problem: liquidity concerns. Of the surveyed banks with less than $50B in assets, more than half said that deteriorations in liquidity positions were a somewhat or very important reason for their decision to tighten lending standards. That is a record high—even beating out the financial crisis period in late 2007/2008, when the question was introduced.

In fact, the Dallas Fed’s May Banking Conditions Survey showed risks regarding liquidity/deposit volume as the most-commonly-cited worry by the survey’s regional-bank-heavy respondents, with 61% placing it in their top-3 concerns compared to 46% that cited financial/economic uncertainty. In a comment, one banker put it bluntly, “Lack of liquidity is reducing the availability of credit.”

Higher-frequency market-based data also confirms this trend: high-yield credit spreads, which serve as a proxy for default risk and borrowing conditions for major risky firms, rose significantly in the immediate wake of SVB’s collapse. In the intervening months, they have steadily declined while remaining above late-2022 levels but below mid-2022 highs. Recent declines could be the first indication that credit conditions are normalizing in the wake of the banking crisis, though it is too early to say for certain.

Welcome to the New Normal

The bank-failure channel of tighter monetary policy is not one the Fed tried to exploit—hence the great efforts undertaken to make uninsured depositors whole and protect the banking system in the immediate wake of SVB’s collapse. Yet the bank-failure channel was activated nonetheless—it’s hard to argue against the bankers themselves when they say liquidity issues, jumpy depositors, and a worsening macroeconomic environment are cause for a more cautious approach to lending.

Luckily, the financial system has gotten some time to adapt—taking on temporary borrowings, reducing reliance on uninsured deposits, building new programs to cushion unrealized losses, and just taking the time to let panic subside. Critically, the banking crisis has thus far remained simply a question of unrealized losses and interest rate movements instead of a question of loan repayments and creditworthiness—actual defaults and loan charge-offs still remain well below pre-pandemic averages even as they rise from 2021 lows—and if rumors are to be believed, we could be at or near the peak of the Fed’s hiking cycle already.

However, it’s worth remembering that there are still risks remaining in the banking system—it was 52 days between the initial failure of Silicon Valley Bank and the failure of First Republic, and markets are currently pricing many smaller institutions as if they are in only slightly better spots than First Republic was immediately post-SVB. For now, things remain quiet—but if 2023 has taught banks anything it’s that crises can move quickly.

Great post.

Hi, Joey. Please write to me at peter.coy@nytimes.com. I have a question.