How Weight Loss Drugs Stopped a Danish Recession

Denmark's Economy Would Be Shrinking—Were It Not For a Massive Boom in Pharmaceutical Exports Driven by Ozempic & Wegovy

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 34,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Obesity is among the most common health conditions in the world. Higher incomes, cheaper processed foods, and more sedentary lifestyles have driven rates up dramatically over the last half-century—especially in the United States, where 42% of adults were classified as obese pre-pandemic. Its consequences can be fatal, with obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and high blood sugar all being leading global risk factors for premature death. Plus, there are intense negative social pressures directed toward people, especially women, who are seen as overweight or obese.

So when a deluge of research came out suggesting that drugs commonly used to treat diabetes could be startlingly effective at inducing weight loss and mitigating the negative health effects of obesity, demand for those drugs skyrocketed. Novo Nordisk, the Danish pharmaceutical giant behind Ozempic (a diabetes drug often sought for weight loss—though not FDA-approved for that purpose) and Wegovy (the new drug explicitly approved for treating obesity), has rapidly become the most valuable publicly traded company in Europe. Sales have risen 30% in the first half of this year, profits are up 40%, and the company is having to ration supply as production struggles to keep up with growth in orders.

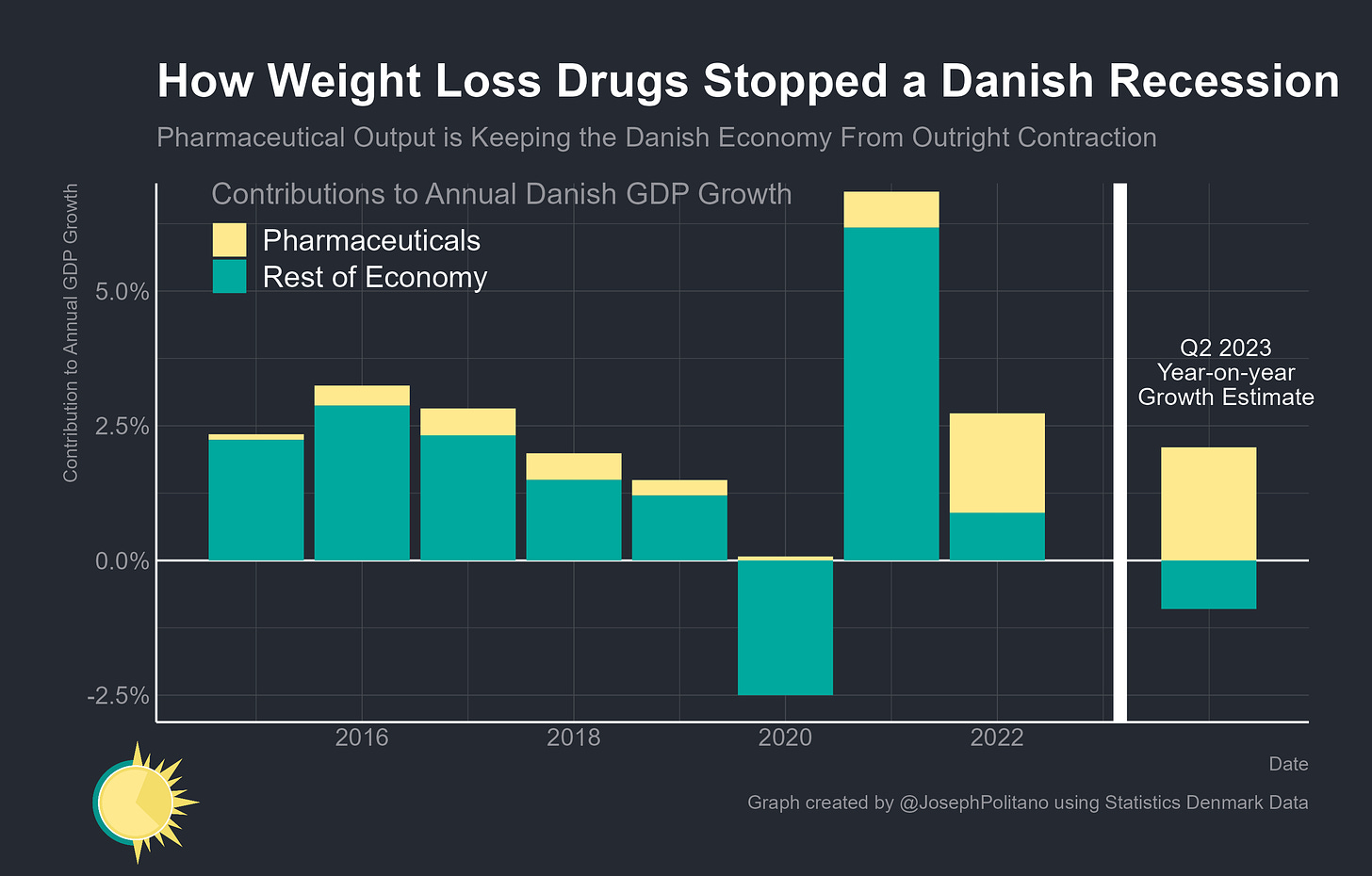

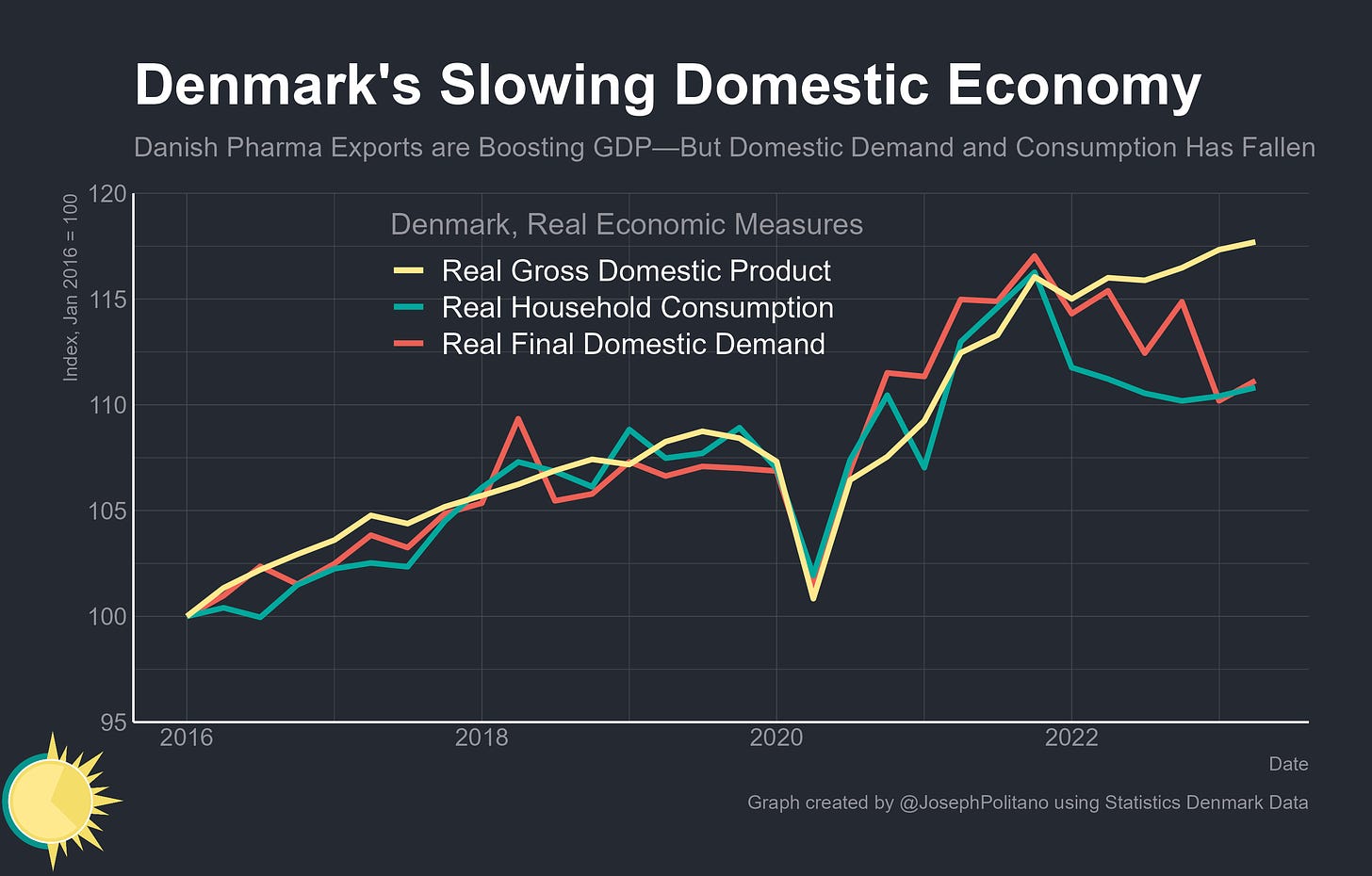

In fact, demand for the drugs is so strong that it functionally prevented a recession in Denmark—headline GDP is up roughly 1.1% over the last year, but excluding the pharmaceutical industry it’s down -0.9%, meaning drugmakers alone have added roughly 2% to Danish economic growth. Booming exports and high dollar earnings are allowing Danmarks Nationalbank—the Danish Central Bank—to keep rates lower than they otherwise would in order to maintain their currency peg to the Euro. The boom’s timing was also almost perfect, helping to cushion Denmark’s economy against both the international shipping downturn that affected their massive international trade-related industries (especially Maersk) and the energy crisis that hit Europe in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

However, the situation is perhaps not as rosy as it first appears—the pharmaceutical industry remains extremely capital-intensive, employs less than 1% of Denmark’s workforce directly, and is primarily oriented around exports via globalized value chains. The increase in drug production and exports over the last year and a half has thus softened, but not prevented, significant recent blows to Danish real household consumption and domestic demand. Yet the bigger picture is one where the rapid growth in GLP-1 medications like Ozempic/Wegovy is already starting to have noticeable effects on the global economy.

Denmark’s Weight Loss Pharma Export Boom

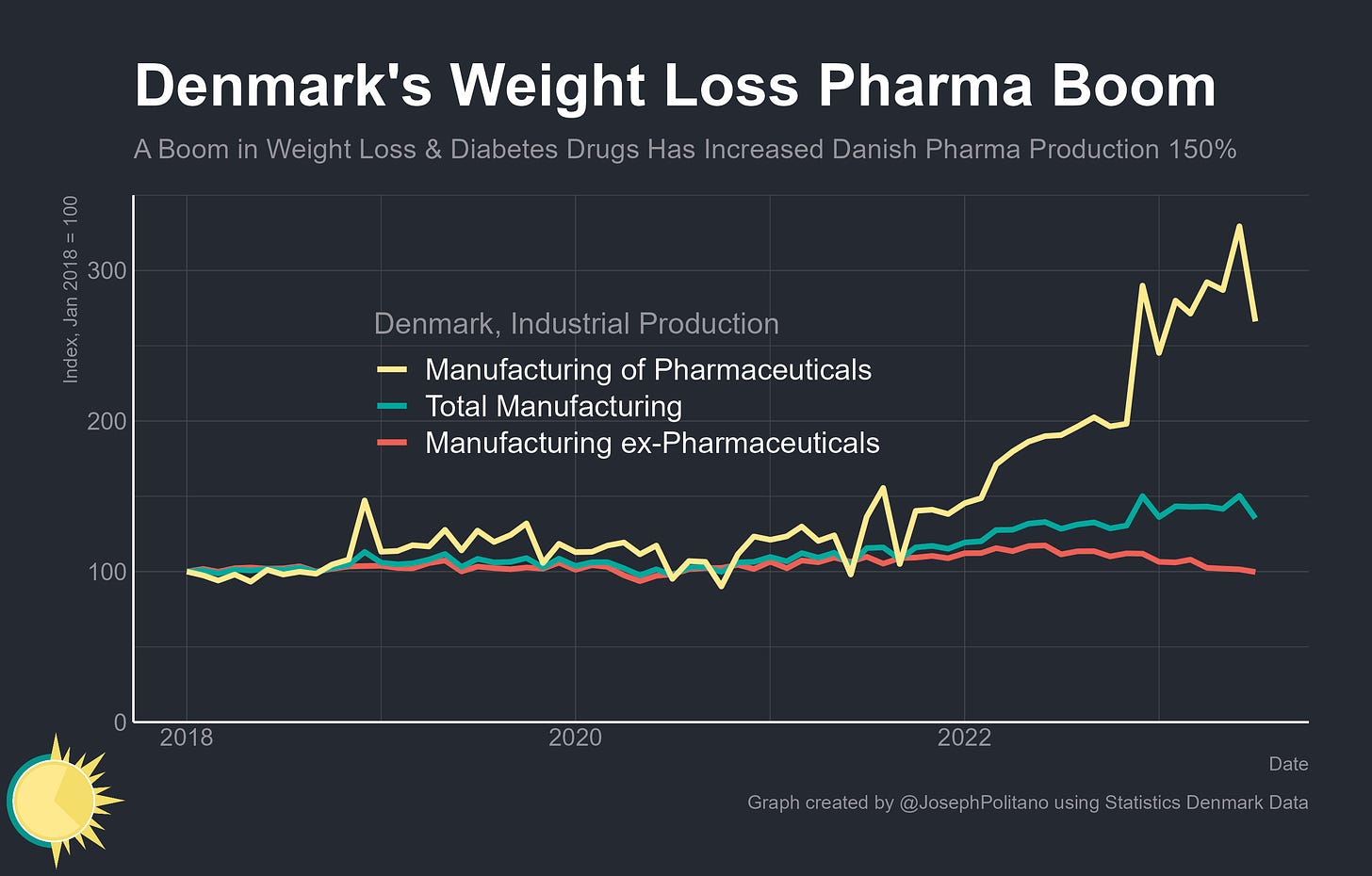

Since 2018, Danish industrial production of pharmaceuticals has increased by 166%, overall manufacturing production has increased by 35%, and manufacturing ex-pharmaceuticals has fallen by 0.3%—in other words, medicine production is responsible for essentially all of the growth in Danish manufacturing output over the last 5 years. Pharma output has been growing at an exponential rate, with production up roughly 40% for three consecutive years leading up to today, and that growth has not been interrupted by the downturn that hit most other sectors of Danish manufacturing in mid-2022.

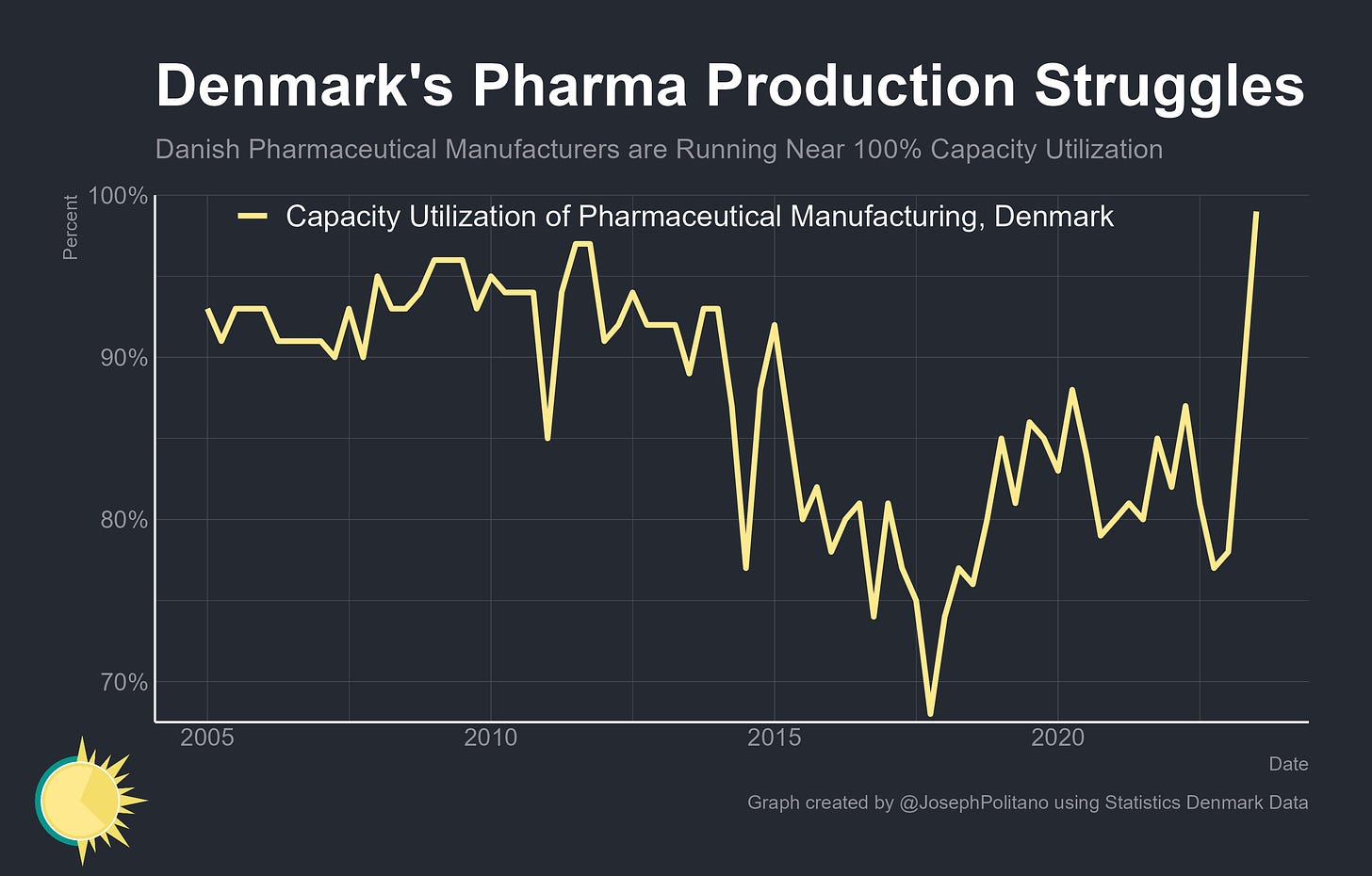

Yet even with this massive increase in production, Novo Nordisk is still struggling to physically meet the booming demand for its weight-loss drugs. As of the most recent quarter, Danish pharmaceutical manufacturers were actively utilizing 99% of their factories’ total capacity, the highest level on record.

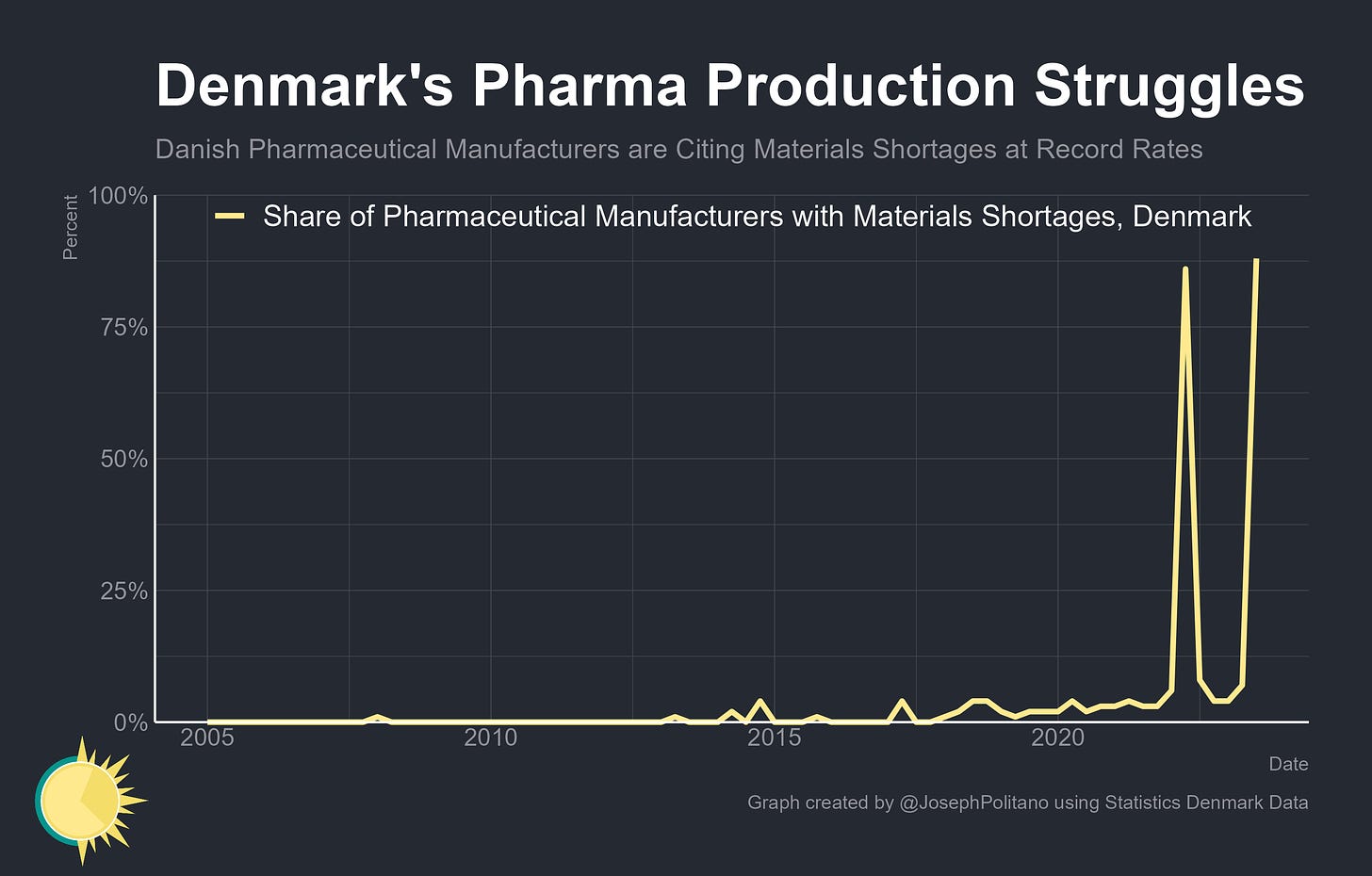

Indeed, Danish drugmakers remain incredibly supply-constrained—acute materials shortages have popped up twice over the last two years in a way they simply never have in the two decades beforehand, reaching levels much worse than during the height of the early pandemic. Unsurprisingly, pharmaceutical manufacturers also overwhelmingly rate their backlog of orders as “more than sufficient” and expect to boost their production, capacity, and employment over the next three months in an attempt to catch up with demand.

Of course, most of the pharmaceuticals produced in Denmark are intended for use and consumption abroad, so the weight loss drug boom has coincided with a significant increase in exports. That export growth has been heavily concentrated in the United States, where the treatments are extremely popular, and has caused the country to definitively pass Germany to become the number one destination for Danish goods exports.

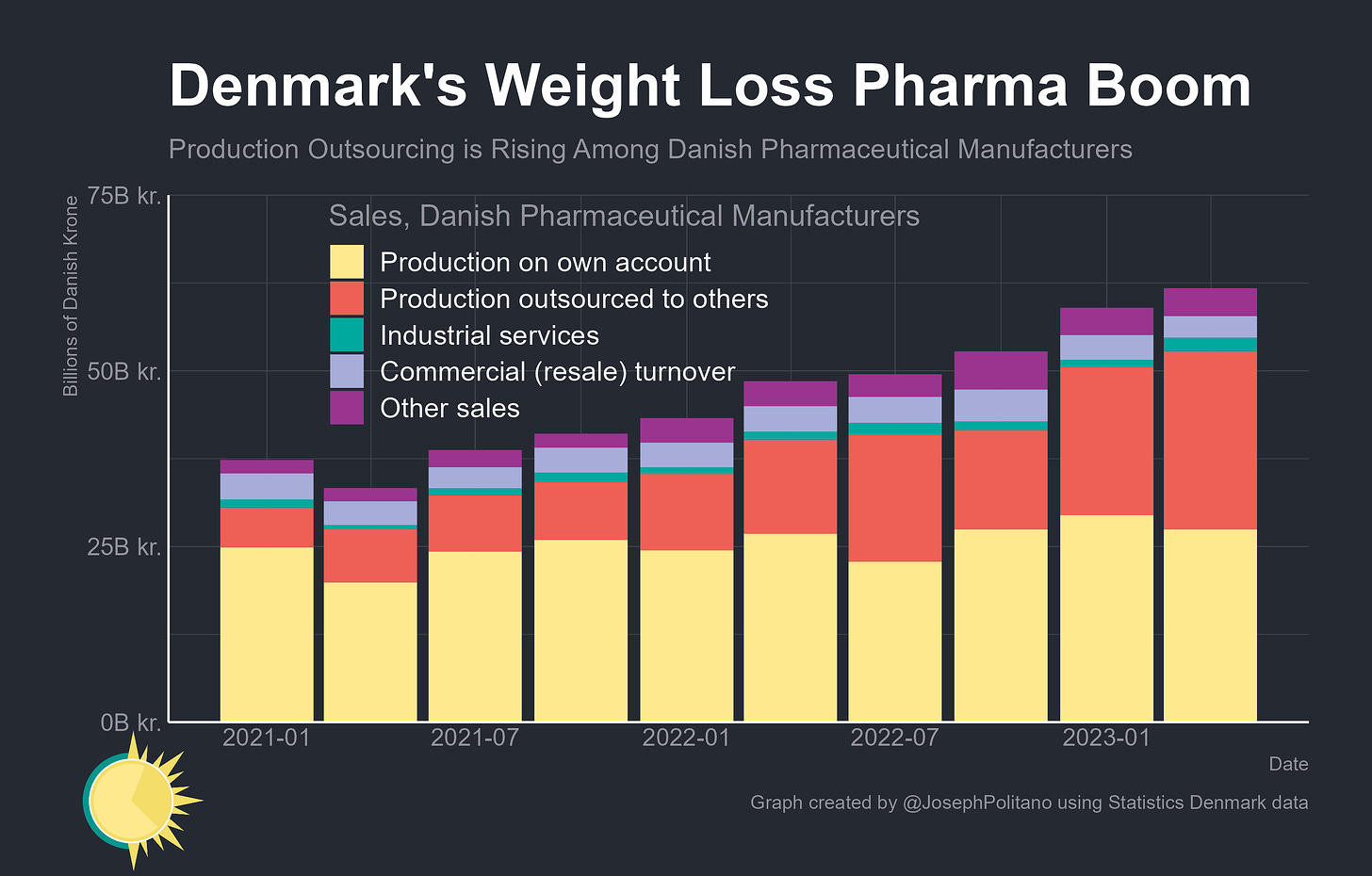

A growing share of those exports, and of the Danish pharmaceutical sectors’ revenues more broadly, are coming from exports of outsourced production as companies work to build out global capacity as soon as possible—in other words, production in Denmark is increasing alongside production outside the country at the behest of Danish manufacturers. Hence a recent boom in goods exports that never cross Danish borders, which reflects the receipts for final sales of Danish-owned goods that were processed abroad by foreign enterprises.

Likewise, a growing chunk of Danish exports now come from charges for the use of pharmaceutical intellectual property and the outcomes of research and development as Danish firms leverage their IP in international licensing and manufacturing deals.

Yet while this export boom has kept Danish real GDP growth positive, it has not been enough to maintain growth in the domestic sectors of the economy. Real household consumption remains well below its late 2021 peaks, as does the real domestic demand series that incorporates government consumption and domestic investment.

The disconnect between pharma’s strength and consumers’ weakness is partially because the pharmaceutical industry is so capital-intensive, with most of the output returned to Denmark coming in the form of returns to intellectual property, profits, and other components of gross operating surplus. As a share of GDP, wages for Danish manufacturing workers—which includes pharmaceutical workers—have been sliding for decades and only recently began picking back up. This disconnect is somewhat normal for global pharmaceutical industries, as firms often invest years of upfront R&D to design the drugs that they produce at large operating profits later. However, it is another part of the explanation for why the extremely large export boom isn’t having a directly proportional effect on domestic Danish household consumption.

Conclusions

In an extremely globalized world, large exporting industries often form within small countries and expand to take up an outsized share of that nation’s economy—a pattern we’ve seen across nations like Taiwan, Ireland, South Korea, and more. The pharmaceutical industry, at 4% of Danish GDP and growing, is now about as relatively important to their output as the state of Florida or Illinois is to American economic output, underscoring the growing need for real-time breakdowns of the sector’s influence. As an example of what that might look like, Norway produces an index of “mainland GDP” separate from indexes on the volatile export-oriented oil, gas, and ocean transport sectors that play an extremely outsized role in the nation’s economy. On that front, there’s some good news: when I reached out to officials at the Danish statistics agency, they wrote back that they’re already considering making the GDP-ex-pharma numbers a regular part of their data releases—for as long as the sector remains critical to understanding their country’s economy.

Yet in many ways, this is just part of the story of the rapid rise of GLP-1 drugs across the world and their growing economic effects. Obviously, it’s hard to speculate about the chances or possible effects of widespread adoption of these drugs when we remain so early in their rollout—but continued growth could have significant effects on food demand, insurance businesses, and the structure of healthcare services. More importantly, if these treatments do provide a durable way of combating the negative health effects of obesity and related risk factors, that could enable millions of people across the world to live happier, healthier, and more productive lives. Compared to that, stopping a recession might look like small potatoes.

Joey, what do you think the long run consequences of Semaglutide will be?

It’s mode of action is to literally lower individual demand for calories. I don’t see how this doesn’t change the world food system in the long run. Also, obesity is so massively correlated with all-cause morbidity and mortality and it’s been getting worse every year for decades and until now nobody ever figured that was going to change, and now oops maybe we cured obesity?

Curious about a more rigorous take on that basic thread.

Ok, I have a few questions: how big of an issue is weight loss in Denmark? And what does Denmark have in pharmaceuticals over other countries like the U.S? Also do you know how much Denmark's government spends on R&D and have pharmaceuticals always made the largest share of GDP or has it grown over time?