The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

In the aftermath of the 2008 recession, American manufacturing nearly completely collapsed. The big three automakers almost went bankrupt. Concrete output was slashed in half. Housing production dropped by 75%. Fixed investment dropped by nearly 15%.

Much of these losses were permanent. In many cases firms simply closed up shop as demand faltered, and in other cases American firms were outcompeted by their counterparts from abroad. Workers either found new service-sector jobs or left the labor force entirely.

When COVID hit, another disaster was foretold. 71% of manufacturers expected a financial impact from the pandemic, and 64% anticipated a recession. American manufacturers braced for another crisis.

Instead, roaring consumer demand caught many companies off guard. Supported by stimulus checks and expanded unemployment insurance while unable to spend money on services, consumers dramatically amped up their consumption of goods. Spending on durable goods is about 30% higher than it was pre-pandemic, and spending on nondurable goods is about 10% higher.

The unprecedented jump in goods demand has facilitated a massive reinvestment in manufacturing across the board. Companies that were caught off guard are scrambling to sort out supply chains and expand production. Investment in machinery and capital expansion is rising to meet the occasion. There are still reams of supply, labor, and capacity issues that need to be worked out, and the road ahead remains rough. But for the first time in a long time, American manufacturing is fighting back.

Recovery and Reinvestment

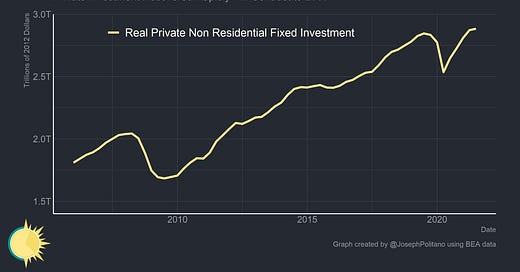

Fixed investment exemplifies the essence of this struggle. In the aftermath of the 2008 recession, real private fixed investment (the creation of productive assets like machinery, buildings, vehicles, etc) completely crashed. Fixed investment never recovered to the pre-Great Recession trend line, and it took years for investment to even reach 2007 levels. In contrast, American fixed investment has recovered rapidly in the wake of COVID-19. Though short of the pre-pandemic trend, fixed investment has already exceeded pre-pandemic levels.

On the flipside, the much-vaunted boom in investment is not as strong as it could be. Business investment remains nearly 6% below trend, making it the biggest shortfall in overall economic output.

American manufacturers, however, are likely not the ones responsible for this shortfall. Manufacturers’ new orders for capital goods have rocketed up nearly 30% since the start of the pandemic and show no signs of stopping. Service industry establishments (which were harder hit by the pandemic and benefitted less from the boom in consumer spending) are likely responsible for more of the dip in fixed investment.

It is worth noting how critical fixed investment is to the long term health of the economy. Fixed investment represents the bulk of how firms expand capacity and increase productivity. Given the slow productivity and capacity growth in the 2010s, especially for manufacturers, the increase in capital expenditures by American companies is a welcome change for the economy.

Transportation in general is also a critical ingredient in the American manufacturing boom. Transportation is both important in its own right—many American jobs come from transporting goods manufactured elsewhere—and a necessary prerequisite for successful domestic manufacturing. The resurgence in demand for rail freight is therefore a good economic outcome and a positive economic indicator. Keep in mind that America’s rail freight network is among the best in the world—in contrast to its underperforming passenger rail network.

Freight traffic rapidly rebounded after the pandemic hit as consumer demand kept the trains rolling. Intermodal traffic (connections between trains and trucks/boats/other vehicles) bounced up dramatically in the latter half of 2020 (these intermodal trips tend to represent transportation of consumer goods). Freight carloads, which disproportionately transport raw materials like coal and oil, rebounded as orders for production inputs rose. In response to the unprecedented demand surge Union Pacific is extending its trains to 10,000 feet long and CSX is beginning to roll out autonomous locomotives. Even industrial production for the rolling stock itself is up. This is in stark contrast to the post-2008 economy when railroad traffic permanently declined and railroad companies were struggling financially.

Some important industries remain constrained by supply chain issues and unable to respond to the surge in demand. Automobile production has barely budged since the start of the pandemic, even declining significantly in 2021 as the semiconductor shortage prevents production.

But it is important to remember that the current production issues are partly a result of the 2008 recession’s permanent scars. The lackluster demand-side response to the Great Recession allowed many American automobile plants to close unnecessarily and left manufacturers skittish and terrified of the next recession. Had automobile manufacturing capacity continued growing in the wake of the 2008 recession we may not face the current level of shortages. Though most of today’s automobile supply chain issues come from abroad, it is also worth remembering that most automakers cancelled their semiconductor orders at the onset of the pandemic because they expected reduced demand. Had manufacturers not gotten accustomed to a decade of insufficient demand, they many not have been caught off guard by the recent surge.

Industrial Production

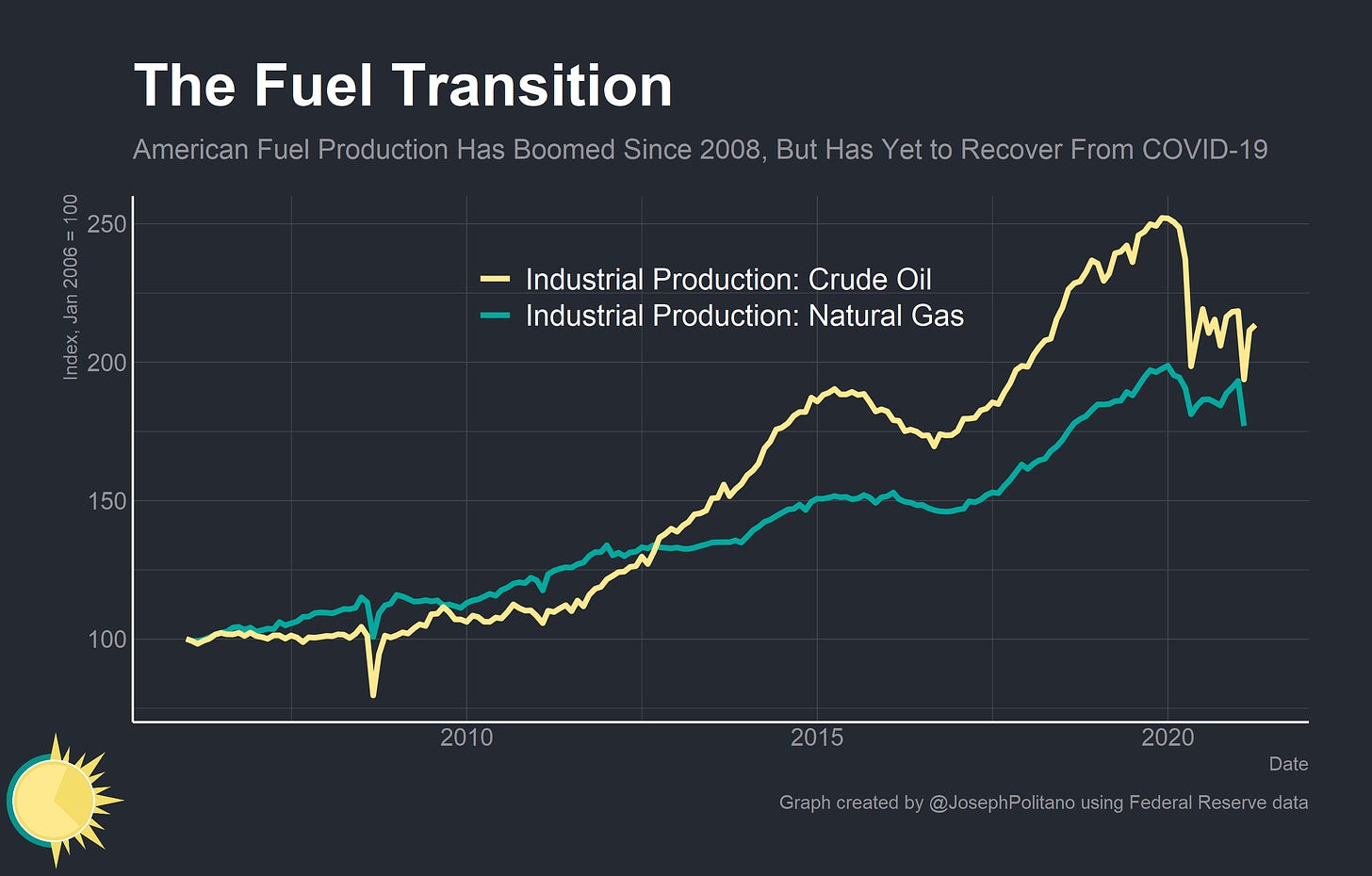

One area where industrial America hasn’t fallen behind is oil and gas production. Buoyed by the fracking and shale oil revolutions, American oil output has more than doubled from 2006-2020 and natural gas output has nearly doubled as well. Today, however, American energy producers are struggling to return to pre-pandemic output levels. Part of this is lag from the drop in oil prices at the start of the pandemic. It takes time to re-start extraction or build new oil rigs, and it will therefore take time for higher oil prices to translate into additional output. Additionally, US oil extraction operates on much thinner margins than their Russian or Saudi counterparts. They are therefore extremely sensitive to fluctuations in oil prices and are only willing to boost output when they are confident in their profitability. The recent 20% drop in oil prices will have likely scared them out of expansion plans for the time being.

High-tech manufacturing is another area where America has excelled over the last decade. Although extremely high-quality chips are mostly the domain of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC), America does have a strong base of conventional semiconductor manufacturing. Output at American semiconductor firms has only accelerated as the pandemic drives demand for electronics and computers of all stripes. Intel has recently broken ground on a $20 billion worth of semiconductor capacity expansion in Arizona, and TSMC itself is starting work on another $12 billion fabricator in the state.

Finally, American production of industrial machinery itself has jumped 30% since the start of the pandemic. The growth in consumer demand is filtering into increased manufacturer demand for machinery and other fixed investment, and this in turn is feeding into increased domestic production. This should be taken as a strong signal for the persistence of the demand shock: manufacturers are expecting the strong economy to continue and are preparing for it by expanding capacity and fixed investment.

Conclusions

Although manufacturing ‘s share of economic output will likely continue shrinking due to the nature of post-industrial economies, a strong and productive manufacturing base is important for long-term economic health. This doesn’t mean attempting to enforce American industrial primacy through counterproductive tariffs and rentierism. What it does mean is encouraging the kind of healthy macroeconomic environment that pushes firms to expand production and increase productivity constantly.

It is also worth keeping in mind the manufacturing employees who are often forgotten in discussions of industrial output. The goods boom has driven record-high wage growth in the manufacturing sector and has driven the quits rate to all time highs as firms are forced to compete for workers instead of the other way around. Just ask UAW workers at John Deere factories who recently went on strike and secured a 10% raise alongside other benefits.

Overall, there is still a long way to go for industrial America to reclaim some of its former glory. But today’s economy represents the first steps towards a renaissance in American manufacturing—one that will be increasingly focused on high-tech goods and high-paying jobs. Aircraft manufacturing will likely rebound as the pandemic ends, and the fight against climate change will require increased manufacturing of renewables. We have dodged the mistakes that cost us so dearly in the last recession, but still need to build on today’s strong economy in order fully seize this opportunity.