Keep Enhanced Unemployment - Forever

The Pandemic Unemployment Programs Were a Key Part of the Current Recovery - We Should Keep and Build on Them

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

25 states, under orders from Republican governors and legislatures, have announced plans to prematurely end the $300 enhanced unemployment benefits offered in the American Rescue Plan. Politicians in these states have blamed unemployment benefits for slow hiring and the difficulty of companies in hiring new workers, essentially accusing workers of living off benefits and deliberately refusing to work. These policymakers have the macroeconomic arguments, and many of the microeconomic arguments, backwards: the enhanced and expanded unemployment programs were extremely critical to the recovery and have marginal effects in keeping individual workers out of the labor market. I should know - having spent the latter half of 2020 on unemployment benefits myself.

Due to America’s federalized system of unemployment insurance and specific language in the CARES Act, there is nothing the Biden administration can do to stop them now. We should instead focus on making sure this never happens again - by permanently enshrining enhanced unemployment in law and working to modernize our unemployment system for the next crisis.

UI Macro: Income Support Works

Many economists will talk about nominal gross domestic product (GDP) targeting or income growth targeting - the idea that macroeconomic policymakers should target a smooth rate of growth in nominal output or nominal income to ensure stability and prevent crisis. While detailed explanations of these policies warrant a blog post of their own, it is worth noting that nominal GDP and income are among the most important macroeconomic variables. The value of capital goods, the decisions of economic actors, and the structures of contracts are all predicated on expectations of nominal growth.

One problem with these regimes, especially NGDP targeting, is that they are coded as monetary policy regimes. In normal times this is fine, as the Federal Reserve can tweak policy to achieve consistent rates of nominal growth. However, in times of crisis and extreme economic stress, it is not enough to simply tweak interest rates and asset purchases. You have to directly provide money to individuals, something only the federal government has the authority to do. So when push comes to shove and the tools of the Federal Reserve are not enough to sustain nominal growth, the federal government must step in to borrow and spend money directly1.

In 2008, the federal government was barely able to scrounge together $1 Trillion in newly passed direct economic stimulus. In 2020, they provided nearly $4.5 Trillion.

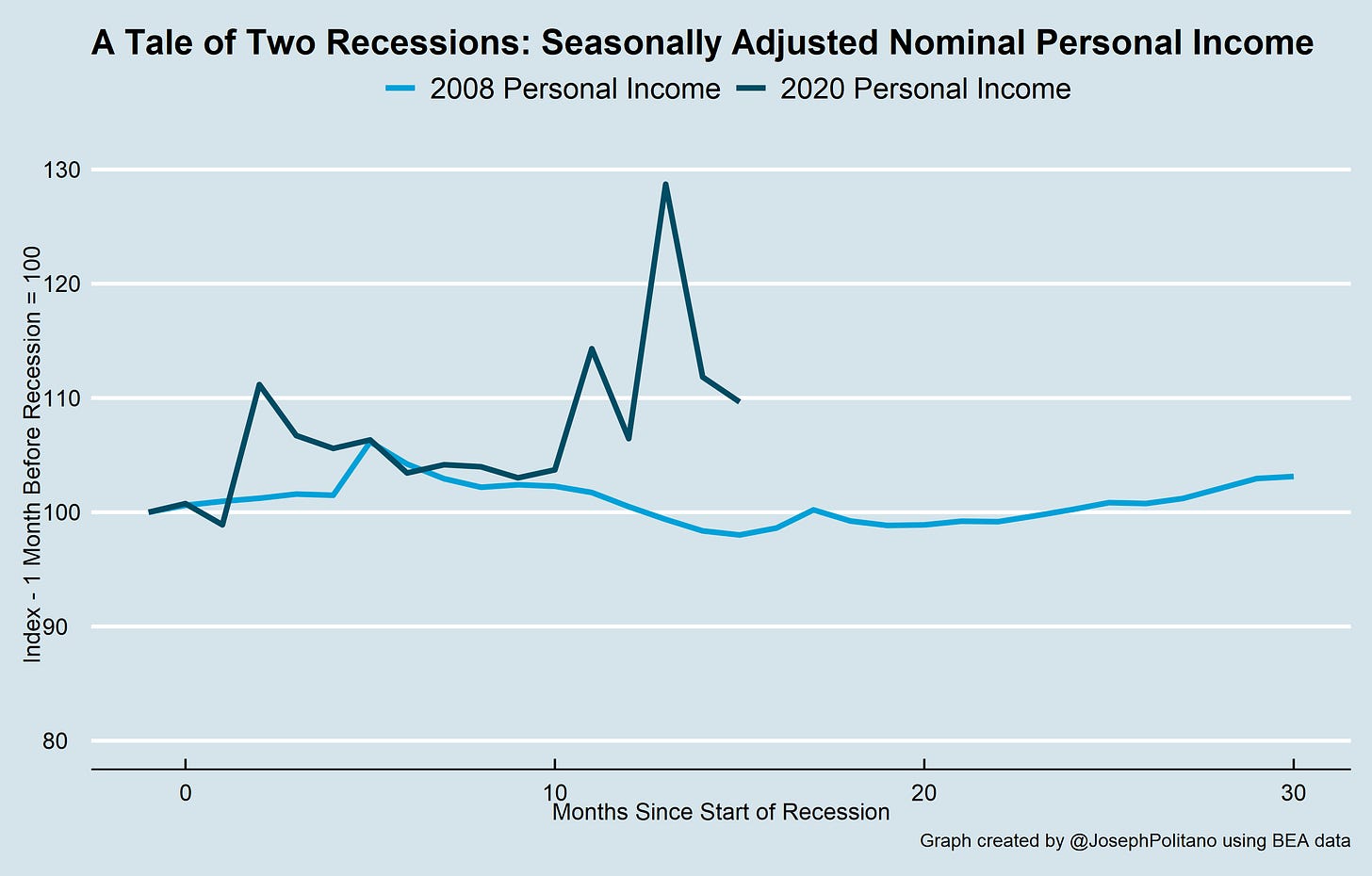

The divergence could not be starker. The graph above shows total pre-tax nominal personal income for both the 2008 and 2020 recessions, indexed to one month before the recession. 20 months after the start of the 2008 recession, nominal income was still below the pre-recession level. Right now, nominal income is 10% above the pre-pandemic level and has been consistently above the pre-pandemic level since right after lockdowns started in March 2020.

Breaking it down, you can see that annual nominal personal income increased more than 6% from 2019 to 2020. Without government transfers, however, nominal personal income would have actually decreased by 6%. The chart above shows that regular unemployment insurance and COVID programs, which primarily consisted of the enhanced unemployment benefits and the stimulus checks, were the tipping point that prevented a stagnation in aggregate personal income.

Supporting personal income did not just allow workers to save money, but actually boosted aggregate demand. In the chart above you can see aggregate nominal personal consumption expenditures, a measure of total consumption spending. While consumption dramatically decreased at the onset of the recession, today consumption has exceeded the pre-pandemic level. At this point in the post-2008 recovery, consumption was actually lower than it was before the recession. When people’s income is uncertain and decreasing, their income expectations and confidence levels fall and they cut back on consumption. When the whole country attempts to lower their consumption by purely saving, aggregate demand decreases and aggregate income decreases again. This is the Keynesian paradox of thrift, and the only way to break out of the cycle of increasing savings and decreasing aggregate demand is to have the government deliberately push to maintain nominal economic growth.

The income support from unemployment and from the stimulus checks has prevented the collapse of aggregate demand that occurred after 2008. The result has been an accelerated recovery from the COVID recession. Guy Berger’s chart above shows that the share of working-age people with a job has already reached the same level that it took until 2015 to reach after the global financial crisis.

This is why, on a macroeconomic level, unemployment insurance actually encourages job creation. If you support the incomes of the unemployed, you bring the economy closer to consistent aggregate demand growth. If you support consistent aggregate demand growth, you stop the self-reinforcing cycle of the paradox of thrift and prevent the economy from shrinking. To put it shortly: the spending of the unemployed keeps other people in their jobs, so crafting an unemployment system where people are fully supported when they lose their jobs will ensure fewer people lose their jobs.

UI Micro: Workforce Effects

Most arguments against unemployment insurance come from a microeconomic perspective: opponents of enhanced unemployment argue that giving people money while they’re not working incentivizes them to just live on the dole and stop pursuing employment altogether. I would argue, from microeconomics and from the realities of the unemployment system, that enhancing benefits has low marginal effects on workers’ employment incentives that are completely outweighed by the macroeconomic benefits of income support.

Republicans have emphasized the work disincentives with a simple argument: when people are making more on unemployment than they would be working a job, their marginal benefit of working is low or negative. The first part of this argument is already flawed, as the graph above demonstrates. The majority of people who received the enhanced unemployment benefits in 2020 found that unemployment income was about the same or less than what they were making at work. This is before accounting for any work benefits, which are extremely important in America because of the cost of private health insurance.

The graph above shows another wrinkle in the anti-UI arguments. Unemployment applications were fairly evenly disbursed across household income distribution, with low-income people actually disproportionately denied unemployment. While I wouldn’t look too deep into the specifics of this chart, as it cannot be matched with data on how long recipients stayed on unemployment and how much money they received, I believe it is extremely important in demonstrating that anyone can become unemployed. Households tend to be extremely illiquid, meaning they have low cash savings relative to their expenses, so they need unemployment insurance to ensure they can pay their bills. In times of crisis, speedy delivery of unemployment insurance is critical.

Additionally, UI opponents are attempting to model economic decision making as one choice between two discrete options at a single point in time. Economic actors do not operate like that, instead seeking to maximize the net present value of their income. This means that when presented with a range of choices they will pursue the one that provides the greatest long term benefit, adjusted for time. Workers in the real world know that getting a job is a gateway to higher paid positions in the future and is a necessity to receive benefits like health insurance, which is why people willingly take jobs that pay about the same as unemployment insurance. Indeed, this is what preliminary research into the effects of the CARES Act’s $600 supplemental unemployment payments suggests. The effects of enhanced unemployment on individual job seeking is marginal.

When I was unemployed last year, I took the first job offered to me. It was something I did not want, in a location where I did not want to live, and only paid me slightly more than enhanced unemployment. I knew that it was the only way to be able to sign a lease on an apartment and that it would be the only way to move forward in life. In short, I recognized that the net present value of taking a job was greater than the net present value of not taking one. It was not a difficult decision, and I have not regretted it for a moment. I eventually landed a job I preferred in a city I wanted to live in, but even if I had not I would still have preferred having the job to being on unemployment.

It is also worth noting that the design and structure of the current unemployment system is almost deliberately crafted to ensure that people are pushed off of unemployment benefits. UI systems deploy unsophisticated hostile design, deliberate choices made to harm users in order to minimize use, in conjunction with general underfunding and decentralization to discourage UI takeup. To receive my benefits I had to check every week for a new designated login window, precisely answer a series of questions during the login window to certify my eligibility, and submit personally identifying information for identity verification. One wrong move, one wrongly answered question, and you are unenrolled from unemployment benefits. Every paperwork requirement makes it that much easier for deserving people to be denied their benefits. The system itself is also ill-equipped for any non-standard requests, which meant it took me nearly seven months to receive unemployment backpay. When you consider that low-income people are disproportionately denied benefits, it becomes clear that our unemployment system is not nearly generous or efficient enough.

Conclusion

The chart above shows, in just one of many ways, how the pre-pandemic unemployment insurance system was too restricted. Under the stringent requirements of traditional unemployment, less than one third of the people currently receiving benefits would be eligible. The pandemic unemployment programs extended benefits to gig workers, graduated students, and the self employed, all groups that are traditionally excluded from benefits.

Unemployment insurance, however, is worth saving. The flexibility and simplicity makes it far superior to the furlough schemes and payments to businesses that many other nations used to force companies to retain workers. As long as the worker is taken care of after losing their job, the unemployment insurance system gives them the flexibility to decide a new career path and find a job where they can be most productive. This is far, far superior to a system that forces employees who would have lost their jobs to do makework for an employer who would have let them go if not for government intervention. It also represents our most important macroeconomic automatic stabilizer, as a good unemployment system will prevent a recession from accelerating by deploying government borrowing to supplant unemployed workers’ incomes.

Reforming unemployment is going to require crafting a system that is deliberately inclusive and generous, instead of the deliberately exclusive and stingy system we currently have. We should extend the eligibility to gig workers, the self employed, employees who involuntarily transition from full-time to part-time, and others who are excluded in the current system. We should build an unemployment system with the technical capability to offer beneficiaries a guaranteed baseline income or 100% of their prior work income, whichever is higher. Unemployment benefits should be bundled with immediate medicaid eligibility and signup. We should build a single centralized system to rapidly process applications and deliver benefits so that we don’t end up attempting to modernize outdated systems in the middle of the next recession.

Finally, we should end state administration of the unemployment insurance system to make sure that state politicians never again have the authority to deprive their citizens of benefits.

The Fed also deliberately constrains itself in important ways. They have consistently signaled an unwillingness to pursue negative short-term rates and hesitancy in pursuing direct intervention in credit markets. While those policies would help boost aggregate demand, they are generally more complicated and inferior to simply increasing fiscal stimulus.