Korea's Trade Troubles

And What it Means for the World Economy

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 23,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

South Korea was poised for a strong economic recovery in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic. A swift public health response, relative isolation, and a robust test-and-trace system made the direct effects of COVID-19 much less lethal. South Korea’s manufacturing industries—responsible for 16% of the nation’s employment and 25% of its GDP—were supercharged by the rise in global goods demand and came out less damaged by global supply-chain crises. As a result, the nation’s economic rebound was comparatively strong and swift, quickly exceeding pre-COVID GDP and employment levels.

Now, however, the winds are shifting against South Korea. The kind of large, high-tech manufacturing goods that the nation excels at exporting—cars, computers, semiconductors, cargo ships, consumer electronics, and the like—have seen demand wane from their COVID-era highs amidst a global economic slowdown and the rebalancing of consumer demand toward service consumption. Meanwhile, prices for the food and energy that the nation must import have surged to new highs—all the while China, its largest trading partner, deals with the aftershocks of COVID, and Korean property prices continue falling amidst higher interest rates. Finance Minister Choo Kyung-ho warned the country will face “a complex crisis for a considerable period” as he pledged support for the nation’s struggling industries. Meanwhile, GDP contracted by 0.4% in the last quarter of 2022.

South Korea could serve as an exaggerated early warning for many parts of the global economy—the Bank of Korea was among the first major central banks to begin raising interest rates in the Summer of 2021, and the nation is overexposed to the manufacturing and fixed investment slowdowns that are now hitting most high-income nations. But even if it doesn’t, Korea’s importance to the global economy and central role in key supply chains make the nation’s troubles important in their own right.

The Shifting Winds of Trade

South Korea reported a significant, sustained goods trade deficit over the last five months of 2022, something they have not experienced since the Asian Financial Crisis of the late 1990s. Although seasonal adjustments and marginally lower energy prices helped bring the country back into a slight surplus in December, the net result is still clear—South Korea is losing significant ground in international markets, and those losses are now holding back overall economic output.

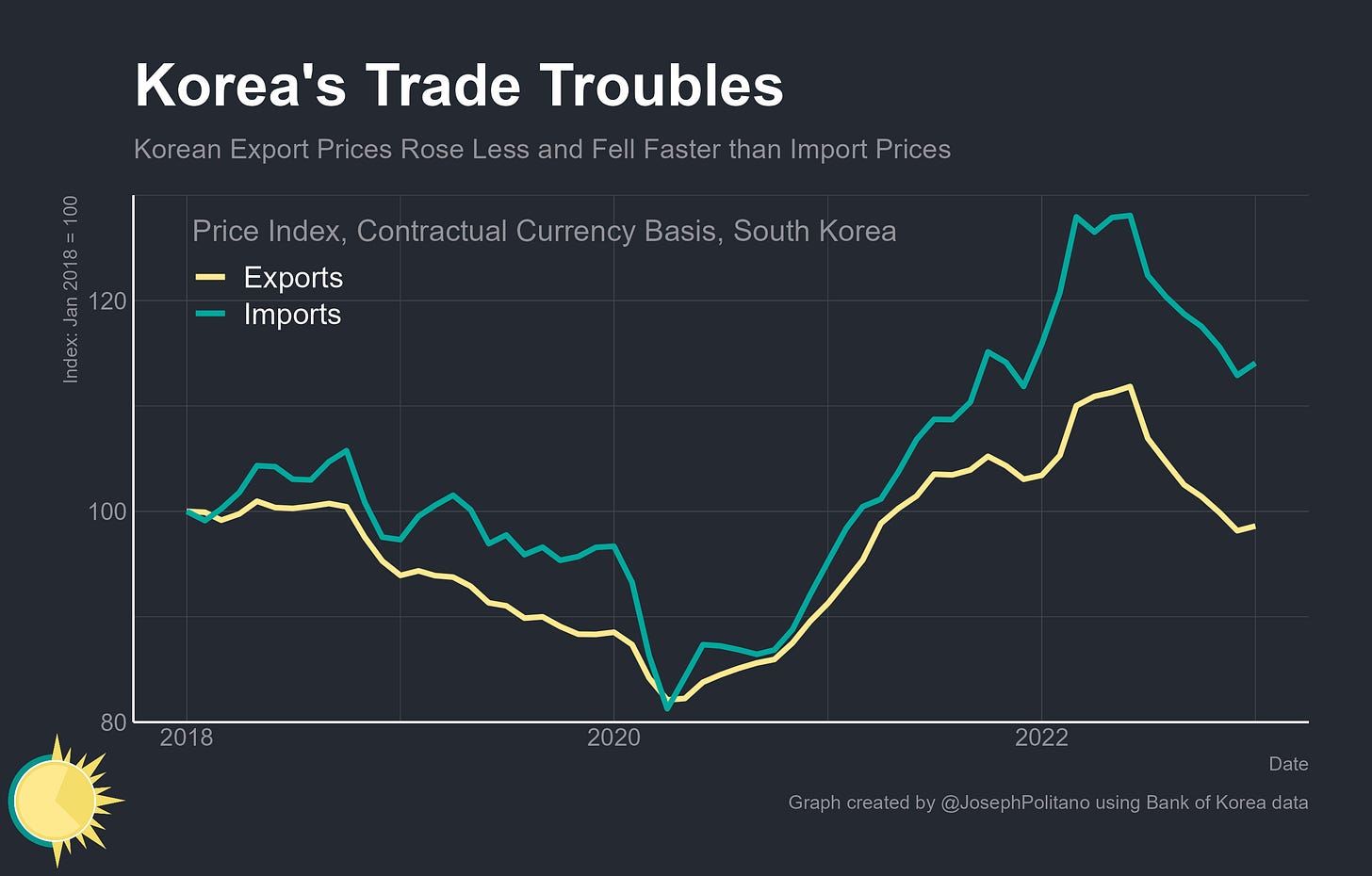

That’s partly because prices for key industrial and household imports rose significantly throughout early 2022 before giving up most of their gains—but prices for South Korean exports have been falling significantly throughout most of the year and have rapidly converged with early-2021 levels. The end result is that the nation is paying much more for critical imports—especially energy, for which Korea was spending nearly $15B a month to import across several months in 2022—while getting less on international markets for its exports.

Indeed, the main culprits for South Korea’s newfound trade deficit have been the rise in prices for Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) imports (which cost a record-high $6.7B in January) and crude oil (which cost nearly $11.5B to import in July but has receded to normal costs levels as global oil prices declined). Imports of coal also added more than $2B a month to energy costs at their peak, pinching the South Korean economy further.

South Korea is reliant on imports for nearly all of its energy needs and is uniquely vulnerable to global market shifts because all those imports must enter the country via seaborne travel. When European nations rushed to international LNG markets to replace lost Russian natural gas supplies, South Korea found itself amongst much fiercer competition for the limited pool of fungible international energy supplies. While they have been able to pay the exorbitant price of energy imports throughout the year—unlike poorer countries such as Pakistan—the comparative cost to the Korean economy was even larger than in most Western European countries.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.