Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 11,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Every month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes an update on the employment situation in the United States—colloquially called “the jobs report.” The name is a bit of a misnomer; there are actually two reports embedded in the employment situation release. The first is the establishment survey (which asks businesses “how many employees do you have?) and the second is the household survey (which asks people “do you have a job?”). When you see headlines like “U.S. employers added 528,000 jobs; unemployment falls to 3.5%” the 528,000 number comes from the establishment survey while the 3.5% number comes from the household survey.

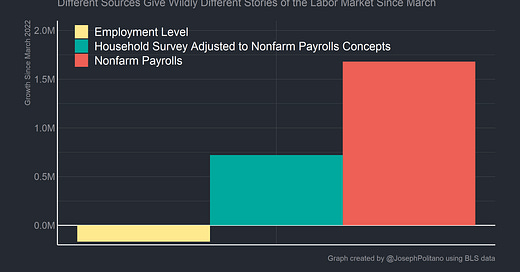

Those two reports, however, are in near total disagreement over the state of the US labor market over the last four months. If you believe the household survey, then 168,000 fewer people have a job than in March. If you believe the establishment survey, then businesses added more than 1.6 million jobs since March. It’s the difference between a strong boom and total stagnation.

Note the precise language though—the household survey measures whether people have a job (the employment level), and the establishment survey measures the number of jobs (the nonfarm payroll level). If a worker takes a second job, for example, this would show up as an increase in the nonfarm payroll level but not the employment level. The number of people with jobs remains unchanged, but the number of jobs increased. The household survey also counts agricultural and related employment while the establishment survey doesn’t (hence “nonfarm” payrolls), and the household survey incorporates the self-employed while the establishment survey doesn’t. So if workers move from self-employment to payroll employment or if they move from the agricultural sector to another sector this would show up as an increase in the nonfarm payroll level but not the employment level.

But even once you account for workers taking on second jobs, leaving self-employment, exiting the agricultural sector, and some other conceptual differences between the two surveys, the household survey would estimate only a 722,000 increase in nonfarm payrolls since March—leaving a 958,000 gap still unexplained. In fact, adjusting the household survey to establishment survey concepts estimates a nonfarm payroll level 1.1 million below official establishment survey data. Plus, placing full focus on the establishment survey’s conceptual framework requires essentially saying that the fortunes of the self-employed and agricultural workers should be discounted and that a rise in people working multiple jobs is a net positive.

So the gap between surveys remains historically large even when adjusted to consistent methodologies—and the divergence comes at a critical moment for the US labor market. If employment is truly shrinking as rate hikes impact the economy then recession risks are more prominent; if wage and employment growth is robust despite rate hikes then the economy could still be in a strong and stable place. There’s of course the possibility that this is a fluke, a data quirk that will resolve itself as more information comes in—but it remains a critical item to watch nonetheless.

Mind the Gap

To review, the main conceptual differences between employment levels and nonfarm payrolls are:

Multiple jobholders count once in employment levels but count twice in nonfarm payrolls

The unincorporated self-employed count in employment levels but do not count in nonfarm payrolls

Agricultural and related workers count in employment levels but do not count in nonfarm payrolls

Let’s go through each of these differences one-by-one to see how they’re contributing to the widening gap between the two data series.

Multiple jobholding fell dramatically at the start of COVID—dropping more than 30% in the first few months of 2020 alone. Since then, it has slowly rebounded and now sits at 7.6 million—more than 90% of pre-pandemic levels. Since March alone, the estimated number of multiple jobholders increased more than 260,000—although this data is relatively volatile.

A rise in multiple jobholding is a bit of an economic double-edged sword. Someone who works one part-time job being able to snag another could be a sign of a strengthening economy, someone who works one full-time job being forced to take a second job part-time could be a sign of a weakening economy. However, multiple jobholding is, surprisingly, more common among highly-educated workers than less-educated workers, likely in part due to age effects (younger people tend to be more educated and also could be more likely to hold multiple jobs) and the fact that more educated workers have more job opportunities in aggregate.

But pre-pandemic multiple jobholding rates were mostly acyclical—the number of workers with more than one job decreased or increased almost exactly proportional to the total number of workers in the economy. The multiple jobholding rate sat at 5.2% at the start of 2007 and 5% at the start of 2010 even as the unemployment rate shot up from 4.6% to 9.8%. Only at the start of COVID did multiple jobholding rates decline rapidly—from 5.2% in January 2020 to 4% in April of that same year.

The rise, therefore, seems to be mostly about a renormalization of demand in the key service-sector industries in which workers tend to get second jobs: leisure, hospitality, food service, healthcare, etc. The number of people who are working part-time for economic reasons is at a 20-year low, consistent with strong, not weak, labor demand. We have also seen a marked rise in the number of workers working two full-time jobs—a highly volatile datapoint that could be climbing up thanks to the remote work revolution. The number of workers with two part-time jobs, however, remains 15% below pre-pandemic levels—consistent with strong overall labor demand and weakness in the specific sectors most likely to hire part-time workers.

Self-employment, on the other hand, recovered rather rapidly after the initial COVID shock and actually reached a post-Great-Recession high in late 2021. Since then the number of unincorporated self-employed workers has begun to slide back down to pre-pandemic levels, with their number dropping 300k since March alone.

This number also deserves some scrutiny—although healthy self-employment rates are associated with stronger labor markets and greater economic dynamism, there’s good reason to believe that the jump in self-employment in 2020-2021 was juiced by some less-than-perfect jobs. For example, if someone’s primary job was working for Uber, Doordash, or other “gig economy” platforms they are technically self-employed, even though many workers were using these platforms out of economic necessity instead of entrepreneurial spirit. If someone was laid off from their 9-5 job, started working for Uber for 9 months, and then picked up a new 9-5 job, the employment level would be unaffected even as nonfarm payrolls declined and then rebounded.

Agricultural employment is the last big conceptual difference between employment levels and nonfarm payrolls, but it is by far the least notable. Agricultural employment levels have barely moved for decades, and although they remain a couple hundred thousand below pre-pandemic levels they are largely not responsible for the data discrepancy.

Besides multiple jobholding, agricultural employment, and self-employment, there are a few less notable conceptual differences between the employment level and nonfarm payrolls:

Workers on unpaid leave count in employment levels but do not count in payrolls

Unpaid family workers in family-owned businesses count in employment levels but do not count in payrolls

Workers in private households (nannies, housekeepers, etc) count in employment levels but do not count in payrolls

Of these, unpaid leave is by far the most important (especially during the pandemic, when unpaid absences have been higher and more volatile)—but even all the conceptual differences combined do not close even half the gap between the change in employment levels and nonfarm payrolls over the last 4 months.

So what else could be driving this remaining discrepancy? Well, heightened immigration is the big possibility; unexpected increases in new arrivals of immigrant workers will push up nonfarm payrolls but won’t push up employment levels (official population levels are only benchmarked intermittently). Visa statistics showed new arrivals increasing significantly in early 2022 (quadrupling their 2021 levels in Q1, and tripling their 2021 levels in Q2) after falling precipitously during the pandemic. But new arrivals were only about 200,000 in the first half of the year, still not enough to close the gap.

Also, the multiple-jobholding and self-employment data used to explain part of the gap is notoriously unreliable. Multiple-jobholding data from the household survey does not seem to match with the extremely comprehensive employer administrative data; in other words people do not seem to consistently report their second jobs on the household survey. Self-employment data is also unreliable; a lot of workers who are technically self-employed sometimes think they are officially payroll employees and the questionnaires struggle to capture the realities of self-employment.

So we’re still left with a situation where the two surveys fundamentally disagree about the path of the labor market over the last four months.

It’s Probably Nothing—But it Could Be Something

Gaps like this are not unprecedented—especially during the pandemic, when data collection is more difficult and fluctuations are much larger. In fact, the first couple months of this year and last quarter of 2021 saw employment levels rising significantly faster than payrolls only for the gap to close later. Payrolls data also get revised as more establishments file their reports and then gets benchmarked to the more comprehensive Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, while household data is final upon publication. It’s possible that further revisions and changes in seasonal adjustments will bring the payrolls numbers closer to the employment numbers—though revisions would have to be historically large and negative to close a lot of the gap. Different official data sources can and have varied significantly for periods during the pandemic, and it is likely this variation will simply fade with time.

Though both sources point to a fairly strong labor market in 2022, the discrepancy remains important if you are looking for a turning point in the US economy. If the country truly is adding hundreds of thousands of jobs per month, a recession is less likely to be currently upon us and the economy could be in stronger shape to withstand further interest rate hikes. If employment growth has truly stalled out, then the economy is much weaker and the chances of a recession are higher. I tend to place more faith in the household survey for live analysis of the economy, but it is impossible to fully discount the establishment survey given the widening gap between them. The true state of the economy likely lies somewhere in between, but only time will tell.

What a difficult paper to write but excellent. I suppose establishment survey is the same as the non farm data but swapping back and fore between them in the post is natural. Yes on a second read it is clearly stated to be so.

Somewhere recently it was said economists have no true theory of inflation. The inherent differences between establushment and household survey suggests the employment data reporting is a problem also. Add to this the fact that the measuring of a recession is up in the air too. It would all suggest a dismal science falling apart with no precise knowledge of its foundational data and so at any given time and even the important times when the various monthly data is released nothing is really known. Is it an assault on economics. I suppose not but it sure makes things confused.

But our host has performed an excellent task highlighting how the consequences are confusing and contradictory with different policy solutions required.

I decided not to edit the typo establushment because it seemed appropriate for the confused state on employment as potentially very embarrassing.

Excellent analysis as always!