Layoffs are at Historic Lows

And Employment Levels are Rapidly Rising

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Back in early January, I wrote that layoffs (or rather the lack thereof) would determine the strength of this winter's job market. Three months later, we now have enough data to assess how seasonal layoffs have impacted employment—and the good news is that despite the Omicron variant few workers have lost their jobs. In fact, layoffs are at historic lows, and there is good evidence that firms have held on to a much larger portion of the holiday seasonal workers who are usually laid off in January.

Thanks to weak layoffs (and extremely strong hiring), employment growth is running at a nearly unprecedented pace. In March alone, the prime age employment-population ratio (which measures the percent of working age adults with a job) increased by 0.5% to 80%. That puts it within another 0.5% of pre-pandemic levels and higher than at any point between summer 2001 and summer 2019. There's still work to be done to reach the highs of the late 1990s (or the 85%+ that many of America's peer nations have achieved), but the pace of progress should not be discounted. At this rate, it is possible that employment rates will exceed pre-pandemic levels in the next couple months and approach all time highs shortly thereafter.

Throw Out the Pink Slips

The Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) measures movement into, out of, and across America’s labor force. It is a critical companion to the normal employment releases, allowing for analysis of the flows of employment instead of just the stocks of employment. This is something always worth remembering—although a declining unemployment rate conjures thoughts of long-idle workers finally returning to jobs, the reality is that millions of people are constantly shifting into and out of employment and the labor force. Job losers only represent between 50-60% of the total unemployed population, and job losers who aren’t on temporary layoffs are only 30-40% of total unemployment. Reentrants (~30%), new entrants (~10%), and job leavers (~15%) compose the rest of the unemployed population.

Layoffs normally run at a fairly consistent 2 million per month, outside of periods of extreme crisis like the 2008 recession and the early months of the pandemic (13 million workers were laid off in March 2020, a number so large that it would make the graph unreadable if included). Hires (and quits) tend to rise and fall much more with changing economic conditions. Normally periods of labor market contraction are marked by a sharp rise in layoffs and a decline in quits and hires. By contrasts, periods of expansion tend to have normal layoffs but rising quits and hires. That’s what makes the recent turn so remarkable: since mid 2021, layoffs have hovered around 30% below pre-pandemic levels.

So why are layoffs usually consistent, and why has the trend changed? First: many sectors have extremely high turnover rates. Layoff rates in construction, professional & business services (which includes temporary help), retail trade, and leisure & hospitality are relatively high. In many of these sectors, hiring rates are elevated too—meaning workers are constantly churning through different roles and establishments. Think of the local mall recruiting workers for the holidays, hiring them December and laying them off January. The same worker can be hired and laid off multiple times in one year.

So what makes now different? For one, labor demand is extremely strong in many of the sectors that already had high turnover. Take the Christmas example again: since Americans spend a large chunk of money on gifts around the holidays, employment in goods-related sectors like retail trade and transportation & warehousing tends to jump in December. Then, when consumer demand falls, these seasonal workers are laid off. But this year, layoffs were extremely low in both the retail trade and transportation & warehousing sector, an indication that firms are working to retain more of their seasonal staff.

The recent uptick in workers who are employed part-time for economic reasons may have something to do with this trend: instead of laying off holiday workers, employers simply reduced their hours. This sort of informal contract renegotiation is one way that employers in certain sectors are comping with high labor demand: by converting part-time workers to full time and converting seasonal workers to part-time workers. On the flipside, workers are quitting lower-paying, more inconsistent, and less-productive jobs for better options, leading to a general uptick in job quality alongside job quantity.

Leisure and hospitality exhibits similar trends to the holiday-affected sectors, but for the opposite seasons; workers are hired for the summer and laid off in the fall. But amid high labor demand, layoffs were extremely weak this fall and have fallen to historic lows this winter. Meanwhile, hires and quits have surged as employers compete with higher paying (and more COVID-safe) sectors for employees.

Some more good news is that layoffs look to remain low going forward. Initial weekly unemployment claims, which are a more high-frequency and up-to-date measure of layoffs, are below pre-pandemic levels. As a percent of the civilian labor force, the number of initial claims has never been lower.

Keep in mind that all of this is despite the negative effects of the Omicron variant. The percent of workers in leisure & hospitality who were unable to work because their business closed due to the pandemic rose from 2.6% in December to 5.6% in January. That compares with a jump from 1.1% to 2.5% in transportation & warehousing alongside a jump from 1% to 2.8% for retail trade. Thankfully the pandemic has had less impact on the economy and labor market in the Omicron variant’s wake.

Omicron’s Wake

In January 2022, a record number of Americans were out of work or working part-time due to Omicron-induced sickness. In the months since, however, the pandemic has had much less of an effect on the labor market and the number of sick workers dropped to numbers more consistent with the seasonal flu.

We can also see the effects of Omicron on the number of workers affected by business closures, which rose in January but continued its steady march downwards after. In March less than three million workers were unable to work due to COVID—the lowest number since the start of the pandemic.

Teleworking also rose in January as people returned to Zoom in order to avoid the Omicron variant. Pandemic-induced telework started declining again in February and hit a new low in March. Only 10% of employees are still working from home, and less than 40% of workers in computer and mathematical occupations (the job with the highest share of telecommuters) aren’t in the office.

One more piece of good news: the rise in long-term unemployment caused by the pandemic has been entirely eradicated. As of March, only 1.2% of the labor force was unemployed for 15 weeks or more—the same share as in February 2020. In retrospect it would be easy to rationalize the rapid rise in employment as simply a byproduct of people on temporary layoffs returning to work, but that is not the case. The share of workers in long-term unemployment was higher than in any other American recession besides the 2008 crisis. The policy response to the pandemic prevented COVID from leaving generation-defining scars on the labor market and put us in a situation where employment can grow rapidly.

Conclusions

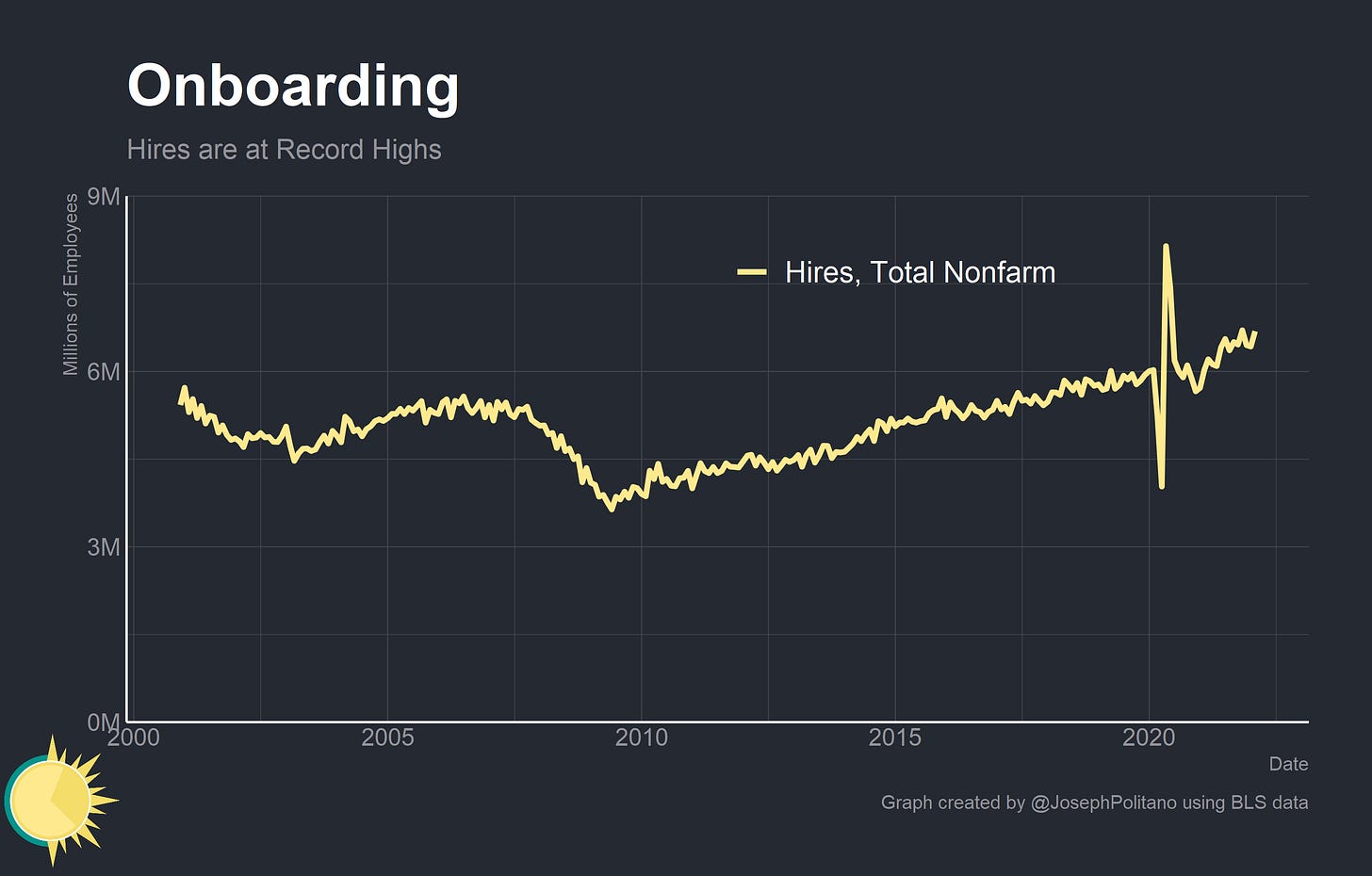

While layoffs are at historic lows, hires are near record highs and continue rising. Going forward, that’s going to be the more critical chunk of the labor market story. The vast majority of workers who lost their jobs during the pandemic have reentered the job market, so continued employment growth will have to come from people who were not previously in the labor force. Indeed, as flows from unemployment to employment have been decreasing, flows from outside the labor force to employment are increasing and near record highs. A lot of that is recent graduates entering the workforce (combined with the consequences of the unclear distinction between “unemployed” and “not in labor force”), but it also represents real progress towards pulling marginalized workers into the job market. In short time, it’s possible that America will have its best labor market since the turn of the millennium.

If you’re subscribed, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work!

"The policy response to the pandemic prevented COVID from leaving generation-defining scars on the labor market and put us in a situation where employment can grow rapidly." So true!

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/the-contrast-between-slow-and-fast?s=w