Mexico's Investment Boom

Major Public Works Projects and Supply-Chain Nearshoring are Driving an Investment Boom in Mexico

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 39,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

The United States has taken a much more aggressive approach to managing its industrial policy over the last several years—spending hundreds of billions to subsidize investments in semiconductors fabricators, car factories, and cleantech manufacturing hubs while placing heavy sanctions, tariffs, and trade restrictions on goods from China and other overseas nations. At the same time, the Mexican economy is undergoing a similar transformation—billions are being redirected toward public investment and a series of infrastructure megaprojects as the country takes a much more active role in managing its national economy. Real nonresidential construction in Mexico now sits roughly 50% above pre-pandemic levels after soaring in late 2022 and throughout 2023, easily dwarfing the relative construction growth seen in the US.

That construction boom has helped Mexico’s economy break out of a long period of relative stagnation—GDP had been stuck at or below 2018 levels for years before growing 4.5% in 2022 and another 2.4% in 2023. Since the start of the pandemic, real gross value added has increased by more than 15% in the construction sector and by nearly 6% in the manufacturing sector, especially in industries like motor vehicles, electronics, electrical products, and home appliances. Indeed, Mexico has a unique advantage in that it can benefit directly from US policy efforts to decouple key industries from China and near-shore manufacturing supply chains while shouldering less of the economic cost of American trade restrictions and Chinese retaliations.

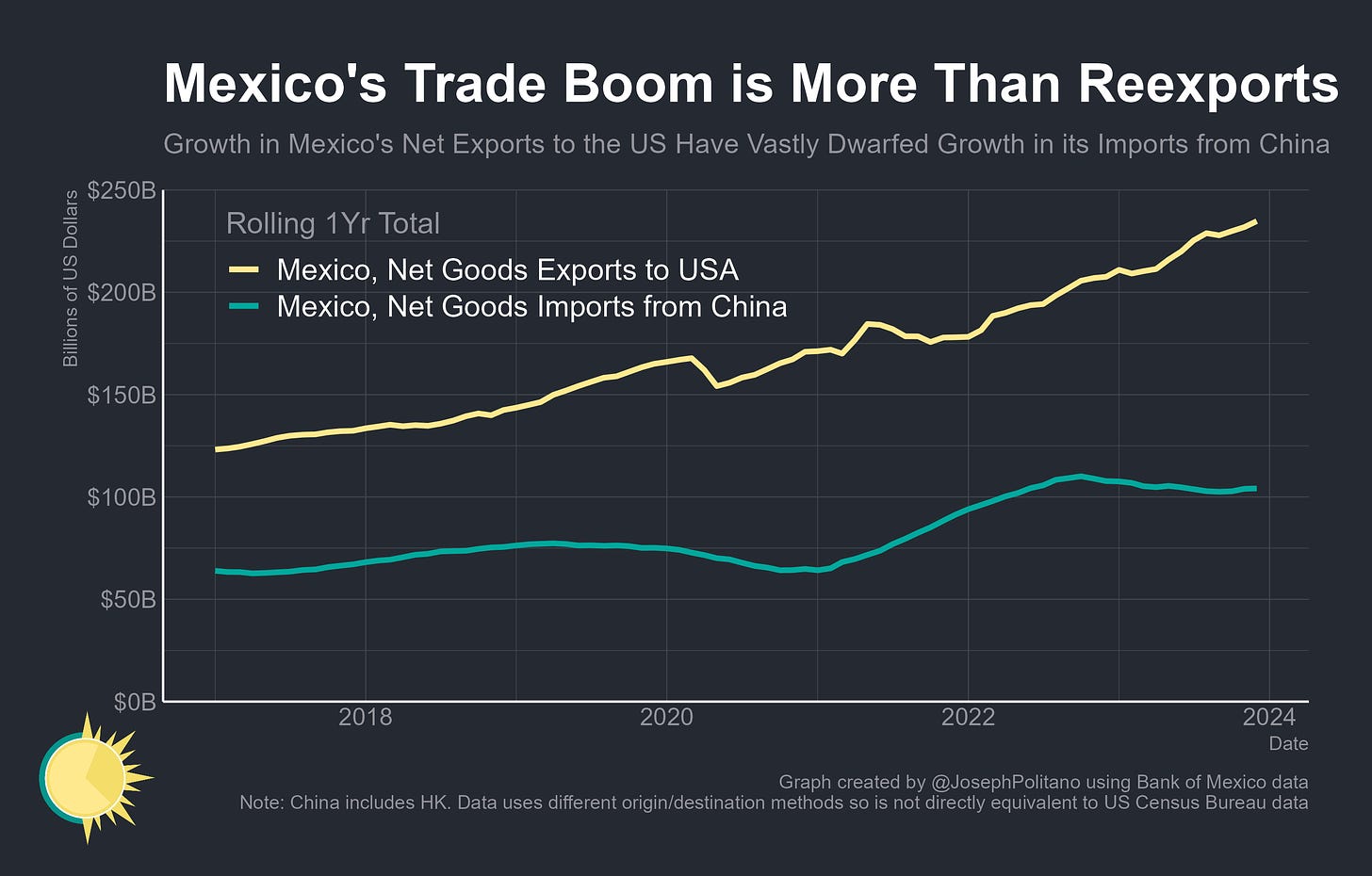

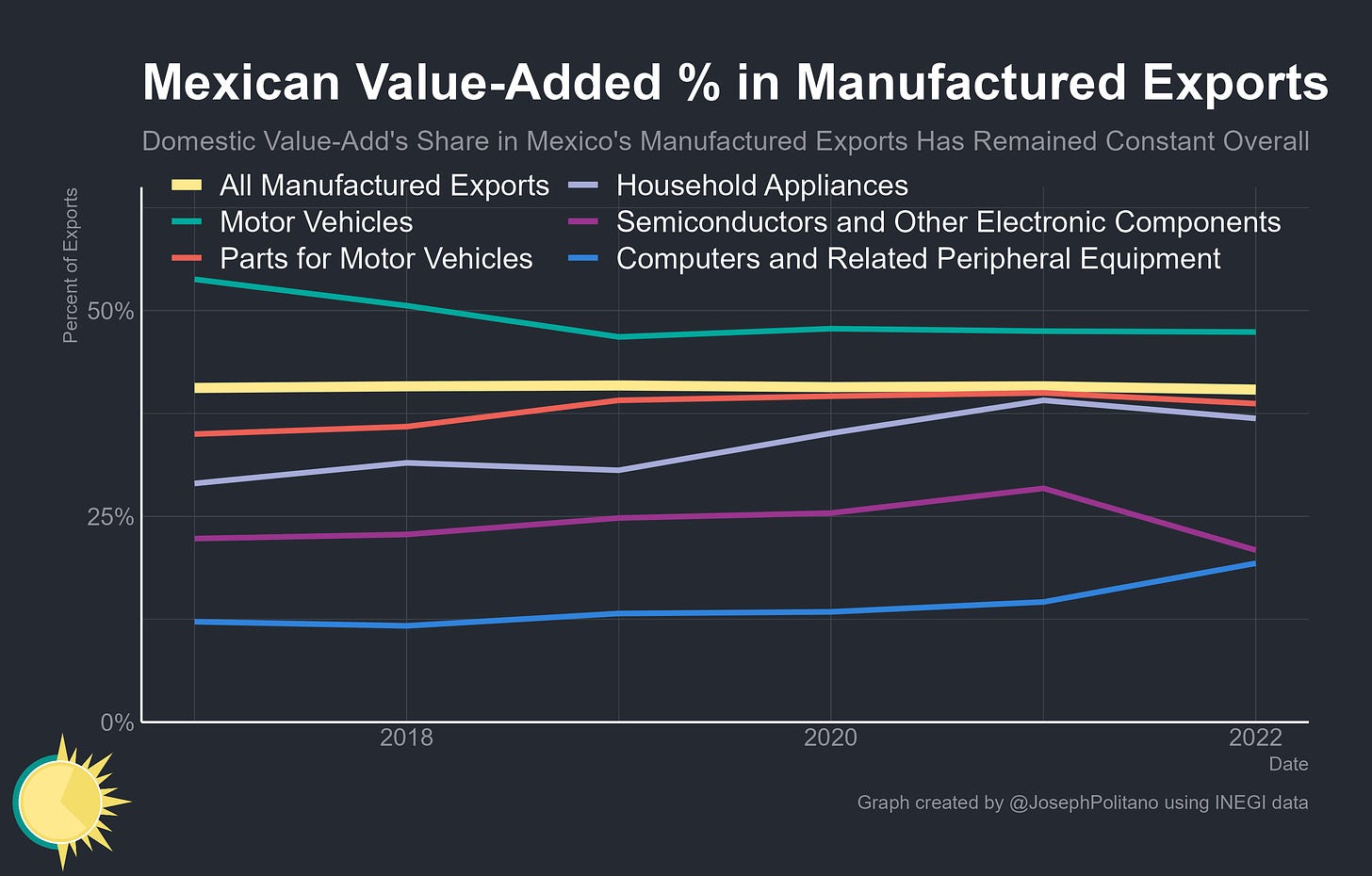

Already, this is paying dividends—Mexico’s northbound net goods exports closed out last year above $225B, a record high despite the country’s increasing imports of American natural gas and other energy products. Of course, the great fear is that Mexican factories are used only for small amounts of packaging and final assembly activity to circumvent tariffs on what are still fundamentally Chinese goods—but so far, that fear has been largely unfounded. Mexico’s net imports from China have grown by significantly less than its net exports to the US, and much of Mexico’s rising imports reflect strong domestic spending on consumer goods and equipment rather than intermediate inputs. Indeed, Mexico’s overall share of value-added in its manufacturing exports has remained relatively constant over the last 5 years even amidst the nearshoring boom. In other words, Mexico is already benefitting from more active US industrial policy and has a chance to become an even larger presence in American markets—if it can play its cards right.

Mexico’s Construction Boom

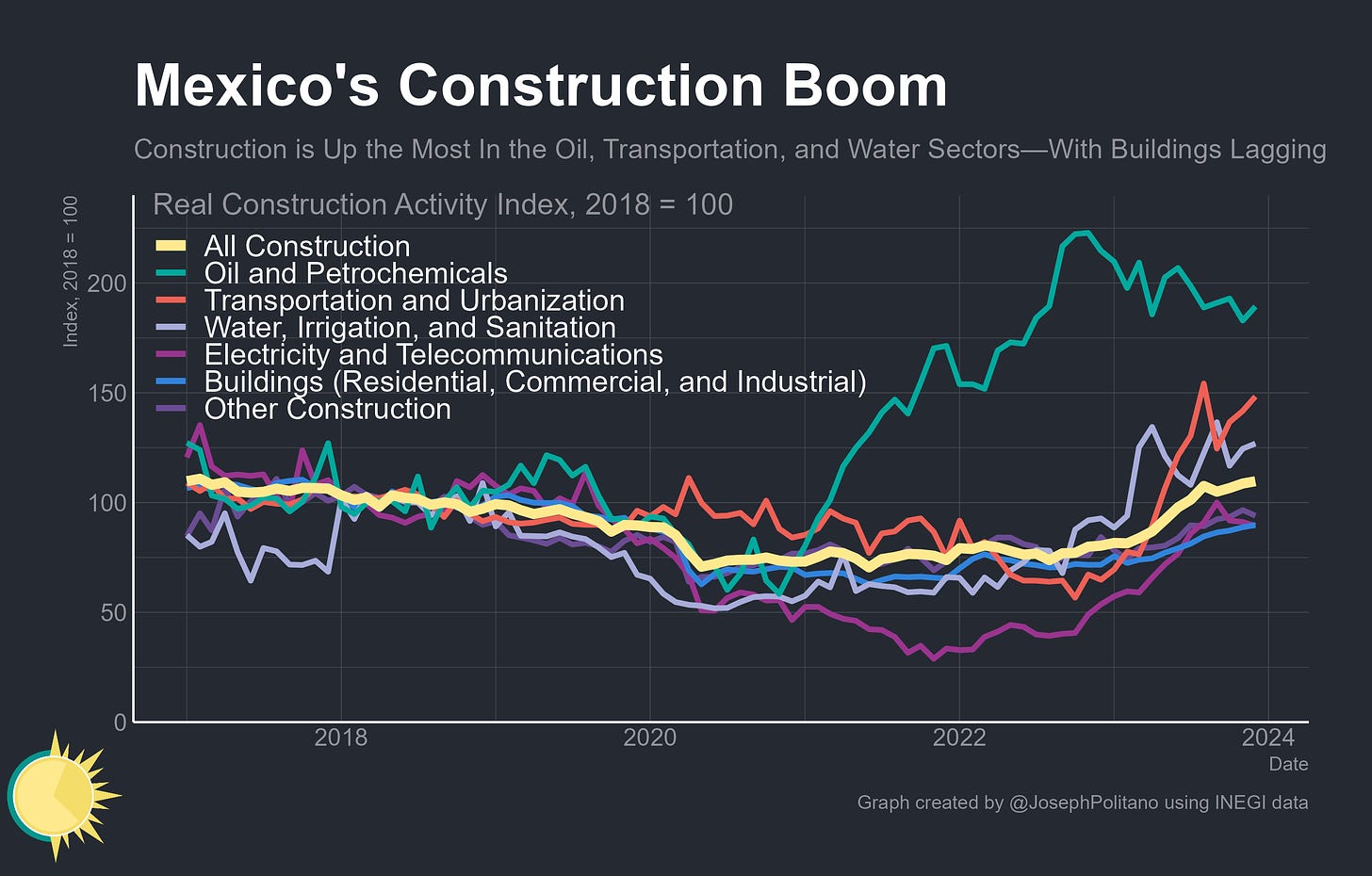

Mexican private sector construction spending has risen by more than 40% since 2019, but the national investment boom has been dominated by a massive increase in public works projects—total government construction spending, which stood at roughly $7.5B a year pre-pandemic, has functionally tripled since 2022. Mexico’s current president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (aka AMLO) sees domestic infrastructure projects as key to his national development strategy and is seeking to finish many of them before his one-and-only term is up this year.

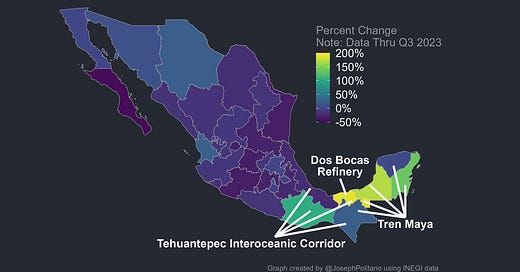

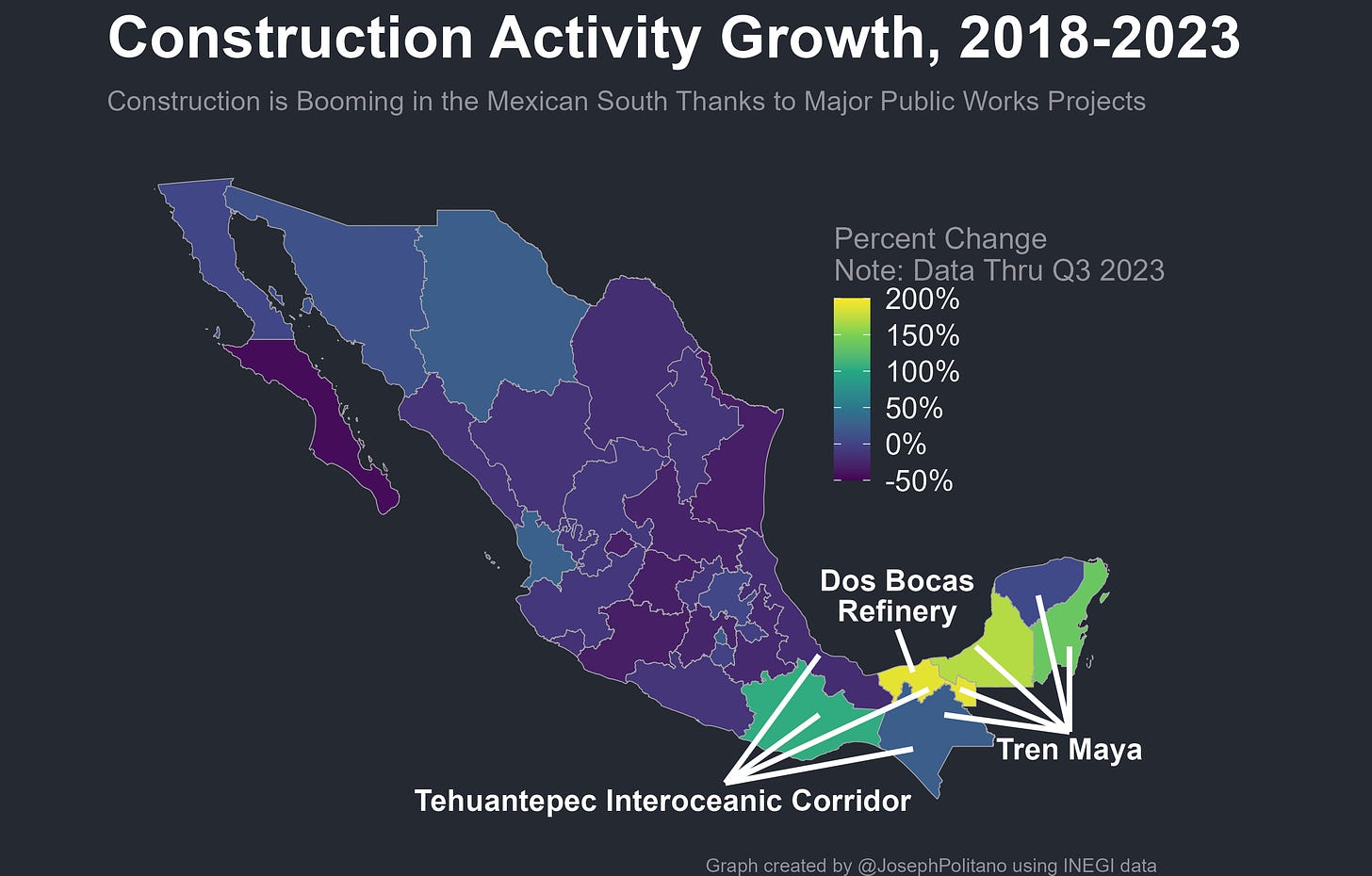

Mexico’s construction boom has been strongest in the nation’s southern states, historically among its poorest, where many of those public works megaprojects are currently underway. First is the Tren Maya, a new rail network throughout the Yucatan peninsula primarily designed to connect Cancun and other coastal tourist destinations with historic Mayan sites and various cities further inland. Then there is the Dos Bocas refinery complex in Tabasco, owned by national oil company PEMEX and designed to increase domestic crude processing capacity while reducing Mexico’s dependence on imported fuels. Finally, there is the Tehuantepec Isthmus Interoceanic Corridor (CIIT), a network of ports, railways, highways, and industrial parks designed to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, compete with the Panama Canal, and kickstart a regional manufacturing hub.

Thanks to Dos Bocas, Tren Maya, and CIIT, real construction activity in the oil and petrochemical sector has doubled compared to 2018 while real construction in the transportation and urbanization sector has increased by nearly 50%. These megaprojects by no means represent the entirety of the public works push either—real investments in electricity, telecommunication, and water infrastructure have also risen significantly over the last year. In contrast, overall construction of buildings has been relatively low, held back by an extremely weak residential sector that has still not recovered from COVID.

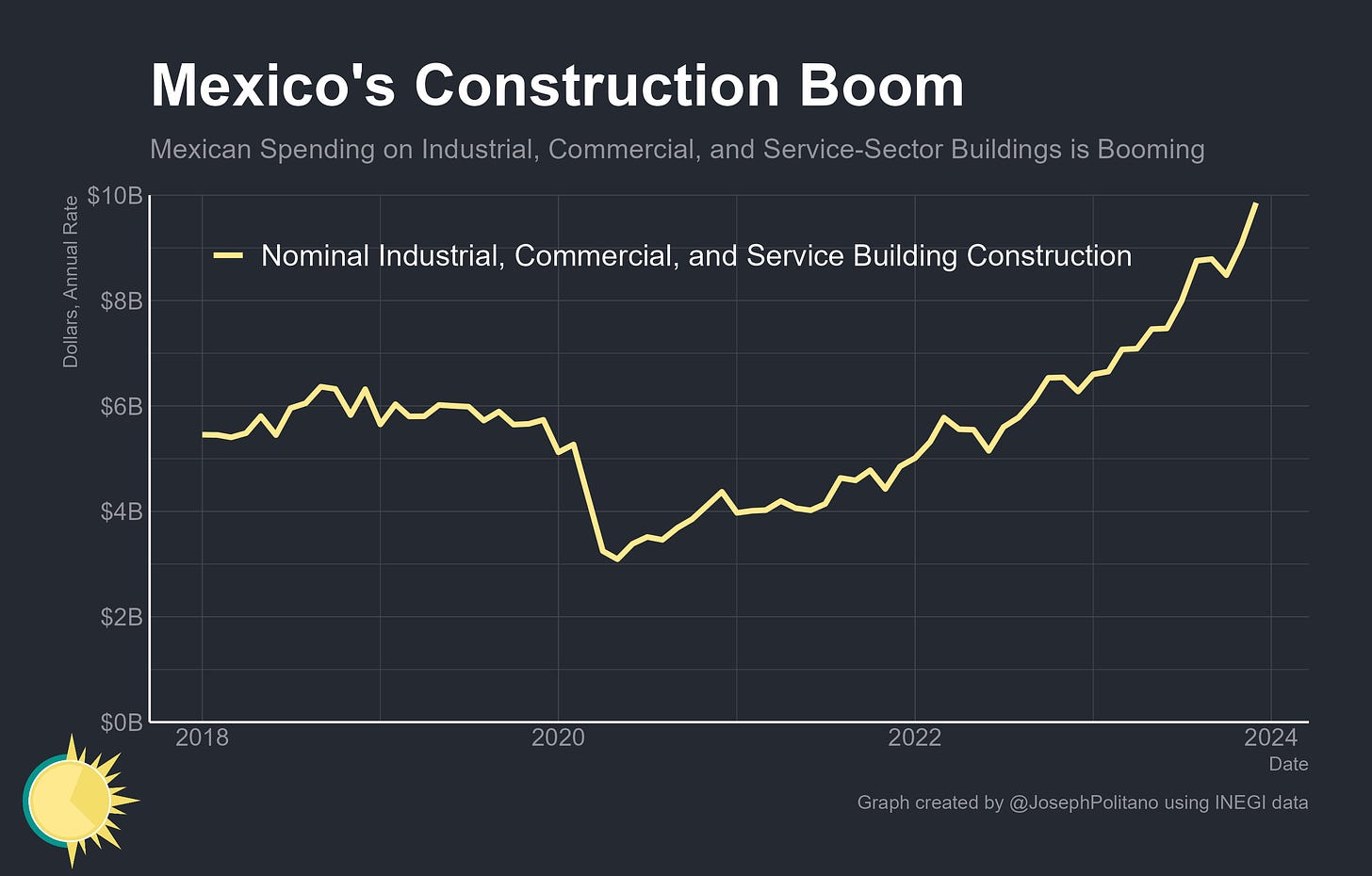

However, the decline in overall investments in new buildings belies significant growth in business spending on factories, warehouses, storefronts, and other facilities. Nominal spending on industrial, commercial, and service building construction is booming, already rising more than 50% from pre-COVID levels and approaching a rate of nearly $10B a year—meaning it now exceeds total spending on domestic residential construction.

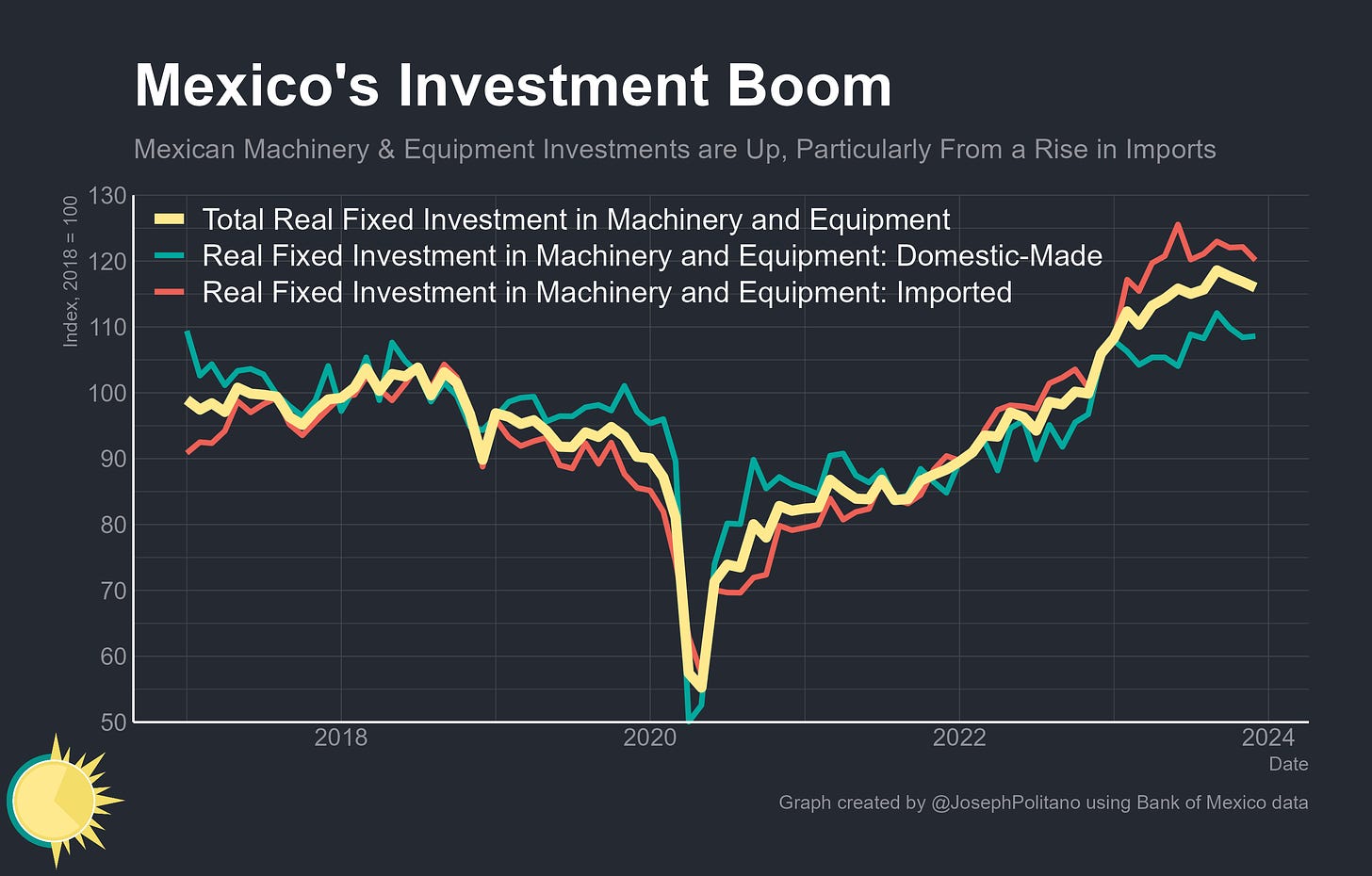

Nor is construction activity the only source of growing investment—it has been complemented by rising real spending on machinery, equipment, and other industrial assets, especially those imported from abroad. All together, the rise in hardware spending, private construction, and government megaprojects drove overall fixed investment to record highs last year. That investment boom is expected to continue into this year—the 2024 federal budget includes significant funds to support PEMEX and continue public works projects while Mexican manufacturers are highly optimistic and rate today as one of the best times in decades to make domestic investments.

Mexico’s Export Manufacturing Boom

Complementing the growth in fixed investment has been a rise in Mexico’s manufacturing exports—by the US government’s count, Mexico surpassed China as America’s number one source of gross imports last year. But to what extent is Mexico genuinely benefitting from that export boom—and to what extent is it just serving to reexport foreign goods while adding little to the production process? Mexico’s export-oriented firms—participants in the IMMEX program (aka Maquiladoras) who receive reduced taxes and preferential treatment to manufacture goods in Mexico for final consumption abroad—have seen a significant increase in revenue from foreign sales of goods made with imported inputs. Chinese foreign direct investment into Mexico has increased significantly since 2016, reaching a record high of nearly 700 million dollars in 2022, although it still pales in comparison to the size of US-Mexico FDI and declined considerably in 2023.

All this data raises alarm bells for those concerned about tariff avoidance and leads to doubt about the actual underlying strength of Mexico’s export industry. It’s likely not true, for example, that Mexico has truly passed China in gross exports to the US, as the trade data does not track the increasingly common extremely small ‘de minimis’ shipments from companies like Temu and Shein and is likely significantly undercounting Chinese exports due to tariff avoidance. Plus, America’s net imports from China still dwarfed its net imports from Mexico last year, and Mexico does not have the dominating global market share in key industries that China has.

Yet it is still true that the majority of Mexico’s export boom is genuine—most tariff avoidance would go through countries elsewhere in Asia and many of the sources of rising Mexican exports are in industries where China has little presence in the North American market, like motor vehicles. It’s also obvious when you look at Mexican manufacturing output—overall production has risen by 5% since 2018 but has been even stronger in export-oriented industries—Computer output is up nearly 25%, appliance and electrical equipment output is up 15%, and motor vehicle production has more than recovered from the effects of the semiconductor shortage.

Breaking down that industrial activity growth further shows it has been fastest in Mexico’s northern states, where most export-oriented manufacturing occurs—Chihuahua, Baja California, and Nuevo León, which alone compose roughly one-third of total Mexican exports, have all seen rapid manufacturing growth over the last five years. Coahuila is the one major laggard, but it has been more than made up for by growth in smaller northern export hubs like Sonora and Tamaulipas plus north-central states like Guanajuato (+12%), Jalisco (+5%), and more.

Plus, Mexican manufacturing employment, while relatively weak overall, has been strongest in the export-oriented businesses that now make up roughly 60% of manufacturing jobs. Since 2018, employment in manufacturers who participate in the IMMEX program has risen by more than 10% while total manufacturing employment has risen by less than 3%.

Yet even amidst the growth of nearshoring, Mexico’s overall share of value-added embedded in its manufacturing exports has remained practically constant throughout the last 5 years. Among major industries, there has been a slight decline in Mexico’s share of value-added in motor vehicle exports and a slight increase in its value-added in the vehicle parts and appliances sectors. Perhaps most notable are the shifts in the electronics sectors where Mexican value-add tends to be low, particularly an increase in computer value-added and a decrease in semiconductor value-added. Given how volatile the semiconductor market has been over the last few years this may be just a blip, but it will still be key to watch amidst US semiconductor sanctions and the CHIPS buildout. Overall though, it’s clear that the rise in Mexican exports largely represents genuine growth in manufacturing activity rather than simply a middleman arrangement.

Conclusions

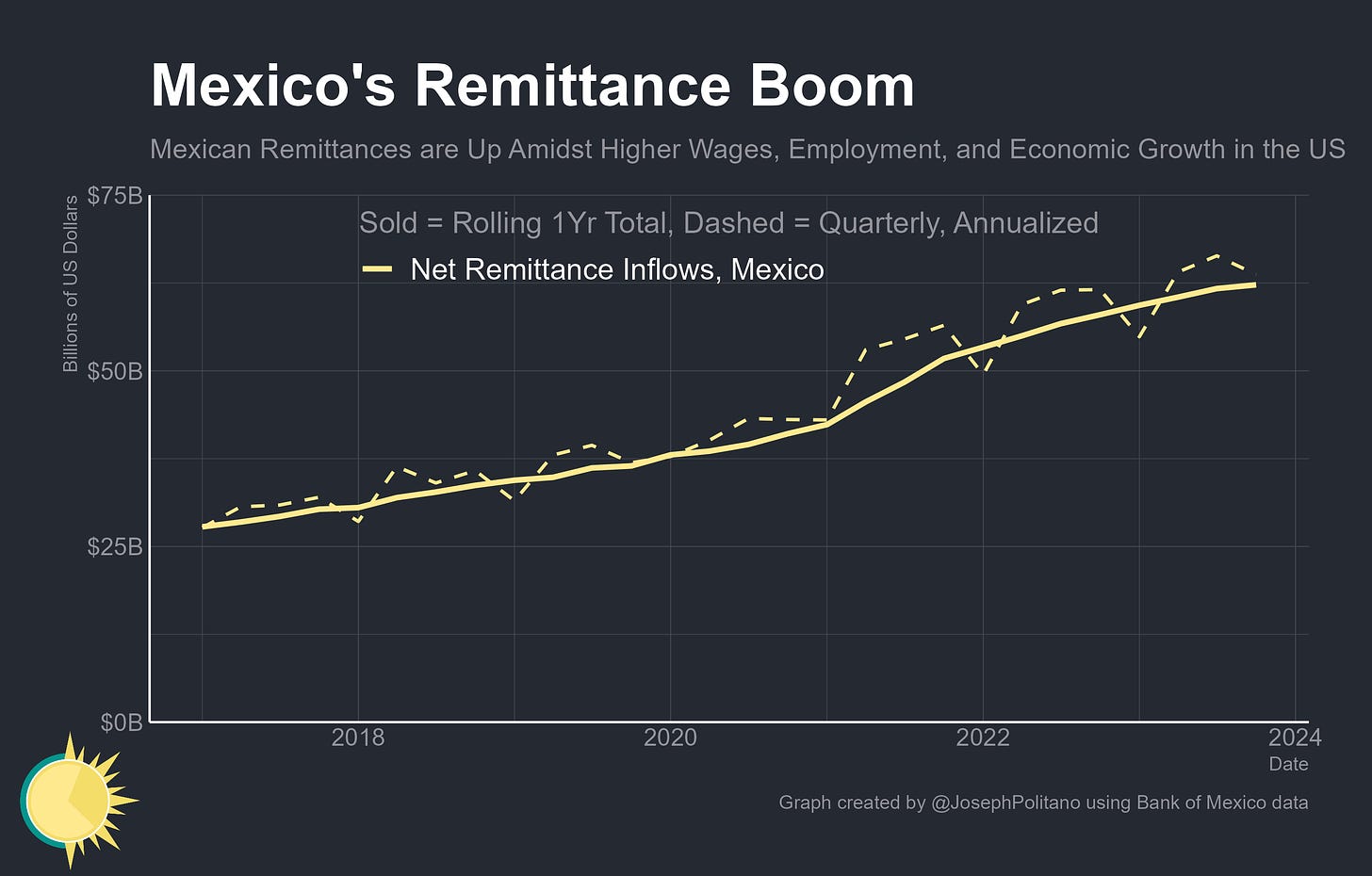

It’s also not just trade and manufacturing supply chains where strengthening cross-border ties are helping the Mexican economy. Net remittance flows have also hit a record high, exceeding $60B over the last year, and now making up more than 4% of Mexico’s overall GDP. Strong US labor markets, with significant pay gains at the lower end of the wage distribution alongside rapid economic growth in states like Texas, California, and Arizona, have enabled many workers to send more back to their families. Plus, tourist flows to Mexico have now more than recovered from the effects of COVID and exceeded a record $20B on net in 2023 as the country becomes an even more popular destination amidst the rise of remote work.

All of this has put Mexican households in arguably their most optimistic mood in two decades—a record share say that their personal finances are improving while the national economy is rated at the highest levels outside the exuberance post-AMLO’s election. Mexicans also rate their likelihood of saving money, buying more household necessities, going on vacation, investing in a house, or getting a car at or near some of the highest levels ever. That is all great news for Claudia Sheinbaum, the former Head of Government of Mexico City who is running to succeed her close ally AMLO as President after his term ends this year. Right now, she holds a commanding lead in the polls and looks extremely likely to win the election when it is held in just three months.

Yet if she wins, Claudia Sheinbaum will inherit an economy that still has significant structural problems—Mexican per-capita GDP growth has been weak for decades, not helped by a manufacturing sector that has generally gotten less productive even as it has grown. Getting a proper return on investment for all this infrastructure spending will be extremely difficult and require prudent economic management, especially considering how far over budget many projects have gone and the large public debts incurred by PEMEX and the national government. Concerns about the economic impacts of deteriorating domestic security and possible corruption are rising, and forecasters already expect the country’s GDP growth to slow this year.

Plus, of course, there is the upcoming US presidential election, where Mexico has more at stake than perhaps any other country. While the current administration sees the growth of made-in-Mexico goods as a success of friend-shoring, not everyone in Washington shares the same definition of friend. Trump—who had previously threatened Mexico with tariffs in immigration negotiations as President, imposed stricter automotive manufacturing requirements as part of the USMCA deal, and is now advocating for universal baseline tariffs—will certainly look more unfavorably on Mexican industry if elected president.

Still, Mexico has the opportunity to make the best of this friend-shoring moment, especially given America’s ravenous goods demand and its economic outperformance over other major global economies. The nation’s car industry has a massive advantage in its efforts to retool for EVs, as its vehicles and batteries can qualify for Inflation Reduction Act subsidies exclusive to goods of North American origin. Mexico manufactured only 106k EVs last year, but was still America’s third-largest source of imported EVs, and right now Tesla is looking to build a major factory in Nuevo León and Chinese EV giant BYD is considering opening production facilities in country. CHIPS Act spending on semiconductor facilities, especially in the American southwest, could also benefit Mexico’s rapidly growing electronics industry. Manufacturing of computers has already risen 60% over the last 5 years, and production of semiconductors and other electronic components is up 30%. So far, America’s renewed focus on industrial policy has genuinely benefitted its southern neighbor, although it is yet to be seen whether it can help kick-start a greater transformation of Mexican industry.

Enjoyed the article. Well researched. Very important as a US based investor to understand the trend of near shoring and the development of the Mexican and Canadian economies post covid.

Good analysis. Thank you for showing this is not just repackaging of Chinese goods. The infrastructure piece is important too.