Monetary Policy in a Shortage Economy

What Can Central Banks Do In an Era of Supply Constraints?

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 19,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

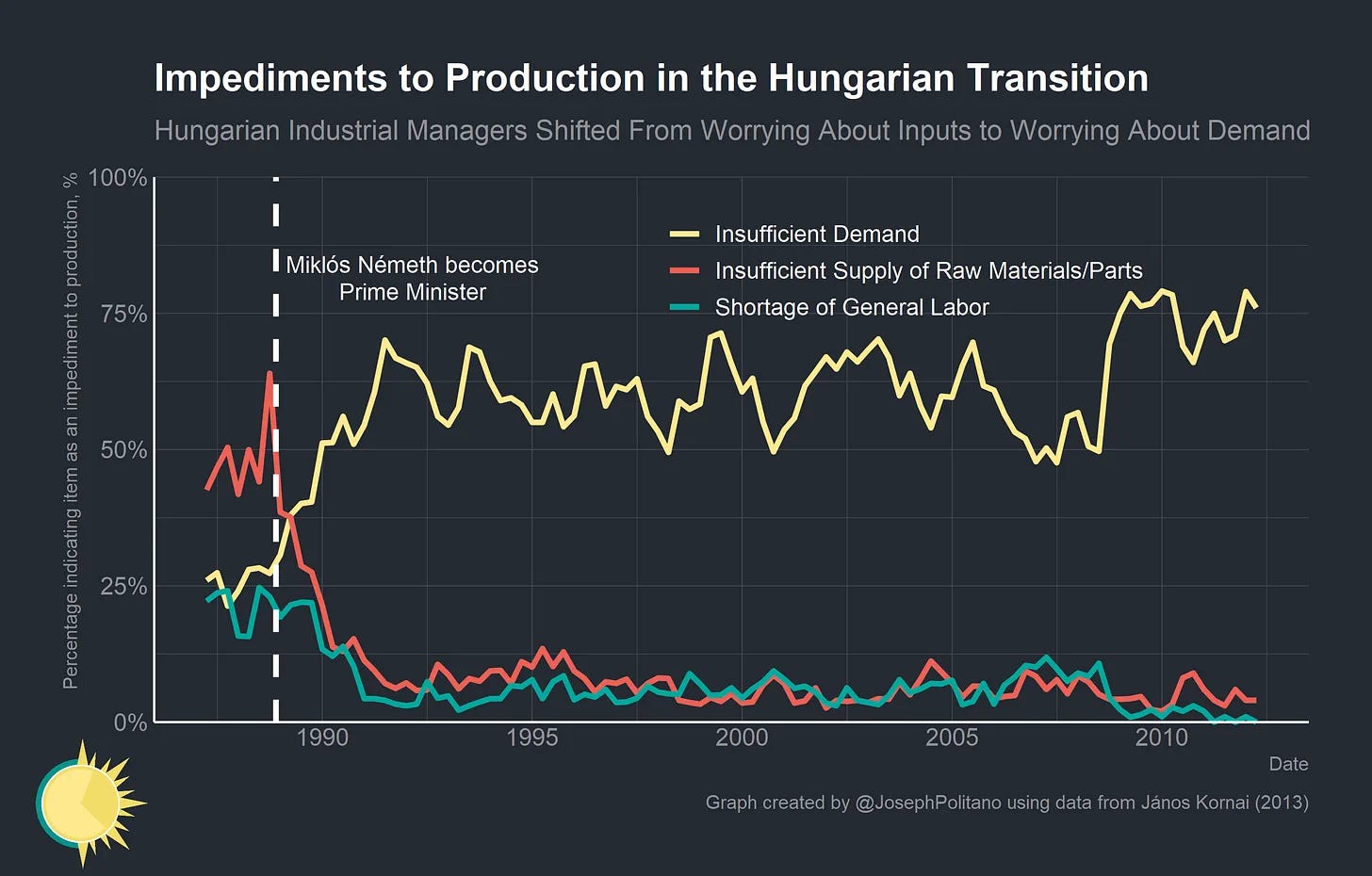

I have been thinking a lot about this chart, and about János Kornai.

Kornai was a Jewish-Hungarian economist who passed away last year at the age of 93. He was a teenager when fascists swept Europe and murdered his father and brother in the Holocaust. As a young adult, he joined the Communist party as a devoted believer and began studying the economies of the Easter Bloc. But he became disillusioned, and his most popular contribution to economics was an unorthodox rebuke of the economic system of the Soviet Union.

In Kornai’s mind, planned economies were fundamentally inferior to market economies—but not in the ways most Western economists thought. Conventional economic wisdom was that government-administered prices led to misallocation of resources, that a lack of inter-firm competition created monopolies that hampered competition, and that heavy redistribution ruined incentives to work, invest and produce. Kornai would retort that Eastern Bloc nations had differing degrees of inter-firm competition with the same stagnant growth, that from a purely technical perspective some Soviet firms were efficiently run, and that if prices were government-set, why were there always shortages and never surpluses? If planners were earnestly guessing wrong, you would expect them to guess a too-high price just as often as a too-low price, yet every manner of good or material seemed in short supply in the Soviet system. Why?

In Kornai’s mind, the answer was more systemic: state ownership of property and the factors of production fundamentally meant that companies were not bounded by profitability or other financial budget constraints. If a firm was unprofitable it was propped up by the state budget, and when no firm is constrained by profitability (and thereby demand) they become instead constrained by the amount of labor and materials they can grab. When everyone tries to grab as much labor and materials as possible, you end up with systemic shortages. By contrast, private ownership of property forces restricts the state’s ability to paper over losses and causes companies to be severely bounded by long-run profitability, so firms in market economies compete on finding demand for their outputs rather than on sourcing their inputs. The soft budget constraint of firms in planned economies leads to a resource-constrained shortage economy, and the hard budget constraint of firms in market economies leads to a demand-constrained surplus economy.

So Why Are We Living in A Shortage Economy?

So what’s so special about the chart? It’s a rare peek into the transition from planned to market economies in Hungary. Before Miklós Németh became prime minister and began Hungary’s transition to capitalist democracy, industrial managers cited material and labor shortages as their biggest impediment to full production—that’s the shortage economy, constrained by resources. After the transition, and for the rest of the duration of the survey, demand was far and away the biggest constraint on production while shortages barely registered as an issue.

That is, until today. If you look at similar surveys from the European Union then a decades-long stable trend of demand-constrained production has been completely interrupted this year, with factory managers citing material or equipment shortages at more than 10 times the pre-pandemic rate.

It’s not just about the European energy crisis, either—American manufacturing firms are also citing materials and labor shortages as major constraints to production at the highest levels in decades. Everywhere you look, supply chains seem to be in disarray—and demand seems to be off the charts.

A large part of the problem is undoubtedly driven by too much global demand, especially for the kind of tradeable manufactured goods that can be moved across the world. But another large part of the problem is undoubtedly supply—from food to energy to semiconductors and manufactured goods, we have seen supply constraints pop up and limit production throughout the pandemic. While writing this newsletter throughout this year I have often found it incredibly difficult to communicate in an accurate way that there is both far too much demand (especially in the United States) and that there are some genuine reductions in capacity stemming from the pandemic and associated supply-chain issues, both of which have contributed to inflation.

But another way to conceptualize this is that the budget constraint exists on a spectrum and can be hardened and softened through monetary and fiscal policy. After all, even in most market economies the military, healthcare providers, regulatory agencies, infrastructure builders, and other institutions are not expected to directly turn a profit—and governments often bail out or heavily subsidize select firms, industries, or other entities. And there are benefits to softening budget constraints—like maintaining full employment, investing in public goods, funding research, or building up high tech industries with positive spillover effects. The key is to strike a balance—too hard a constraint and you end up with elevated unemployment and weak growth, too soft a constraint and you end up with elevated inflation and ongoing shortages.

The Federal Reserve and other central banks help set the relative hardness of the budget constraint through monetary policy and financial conditions, and today’s rapid inflation is evidence budget constraints were left too soft for too long. But conversely, the only tools central banks have is to restrict nominal demand and to restrict financial conditions. Budget constraints are getting harder, but in the short run that impacts supply as well as demand: the share of European firms saying their output is demand constrained has risen, but so has the share saying their output is constrained by financial conditions (though admittedly this is still a much lower total share).

Or maybe the best way to think of this is in terms of budget flexibility, price flexibility, and time flexibility. A softer budget constraint in the very short term when prices are inflexible produces shortage, over the longer term when prices are allowed to adjust it produces inflation.

Why is Inflation Global?

A reasonable question to then ask is: why did every country make their budget constraint too soft? In other words, why is inflation global?

Of course, the situation varies tremendously across countries: compared to the US, inflation in the Euro area has more to do with energy than aggregate demand, and countries like Japan have only barely graced their inflation target.

Part of the issue is that markets for items like oil, food, and manufactured goods are global, but partly it is just that monetary policy errors tend to be correlated across countries. Central bankers mostly communicate policy through interest rate setting, and if one major central bank significantly underestimates appropriate real interest rates then it's likely consensus estimates across the world were wrong. The 1970s were partially a similar story: some countries like West Germany avoided extremely high inflation, but in general global central banks persistently underestimated necessary interest rates. Today, NGDP growth, spending growth, and aggregate demand growth across many major countries is simply too high.

But part of the issue is that monetary policy, or maybe more accurately credit conditions, is increasingly global. If a company can't easily borrow dollars in the US, they can go abroad to borrow in other currencies or vice versa, hence why financial conditions like corporate credit spreads tend to move together across currencies. So credit availability is determined in large part by the aggregate state of global monetary policy, over which the Fed has a disproportionately high amount of influence thanks to the dollar’s role as a global reserve currency. The global business cycle is partly driven by global credit conditions, hence why US monetary policy can have significant influence over global inflation, especially in the short term.

Conclusions

I suggest instead that demand-formation is not composed of two still photographs but it is a movie; a continuous interaction between buying intention (which may or may not be well defined at the beginning) and adjustments to the available supply and vice-versa. Instead of two static numbers (notional and actual), we see an adjustment process. In a surplus economy this process does not run against supply constraints very often, but, even when it does, we witness a certain adjustment of demand to supply.

János Kornai, Dynamism, Rivalry, and the Surplus Economy

Kornai's theories were mostly about the structural long run tendencies of economic systems, with acknowledgments that market economies can and did occasionally encounter short-term periods of acute shortage, especially surrounding shocks like pandemics or wars. The long run tendency is still towards surplus not shortage, so barring fundamental shifts in the nature of the global economy supply constraints should eventually abate.

But the period we're entering will require a hardening of global budget constraints in order to end the shortage economy. Few expect the transition back to normal surplus economies to simply occur naturally any more, and central banks are focused on ensuring that shortages don't morph into runaway price increases. How hard budget constraints must get and how quickly economies can structurally renormalize remains the biggest open question in today's global economy.

I’ve always found the Shleifer Vishny story compelling https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shleifer/files/pervasive_shortages.pdf

Ebb and Flow - so many events in life, nature and economics not only reflect this to and fro but are a requisite adjunct to how everything homes into its targets by varying trajectories, directions and velocities of change. Thanks Joseph and Happy Holidays.