Monetary Policy in a Surplus Economy

What the Fading of Pandemic-Era Supply Constraints Means for the Economy

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 35,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

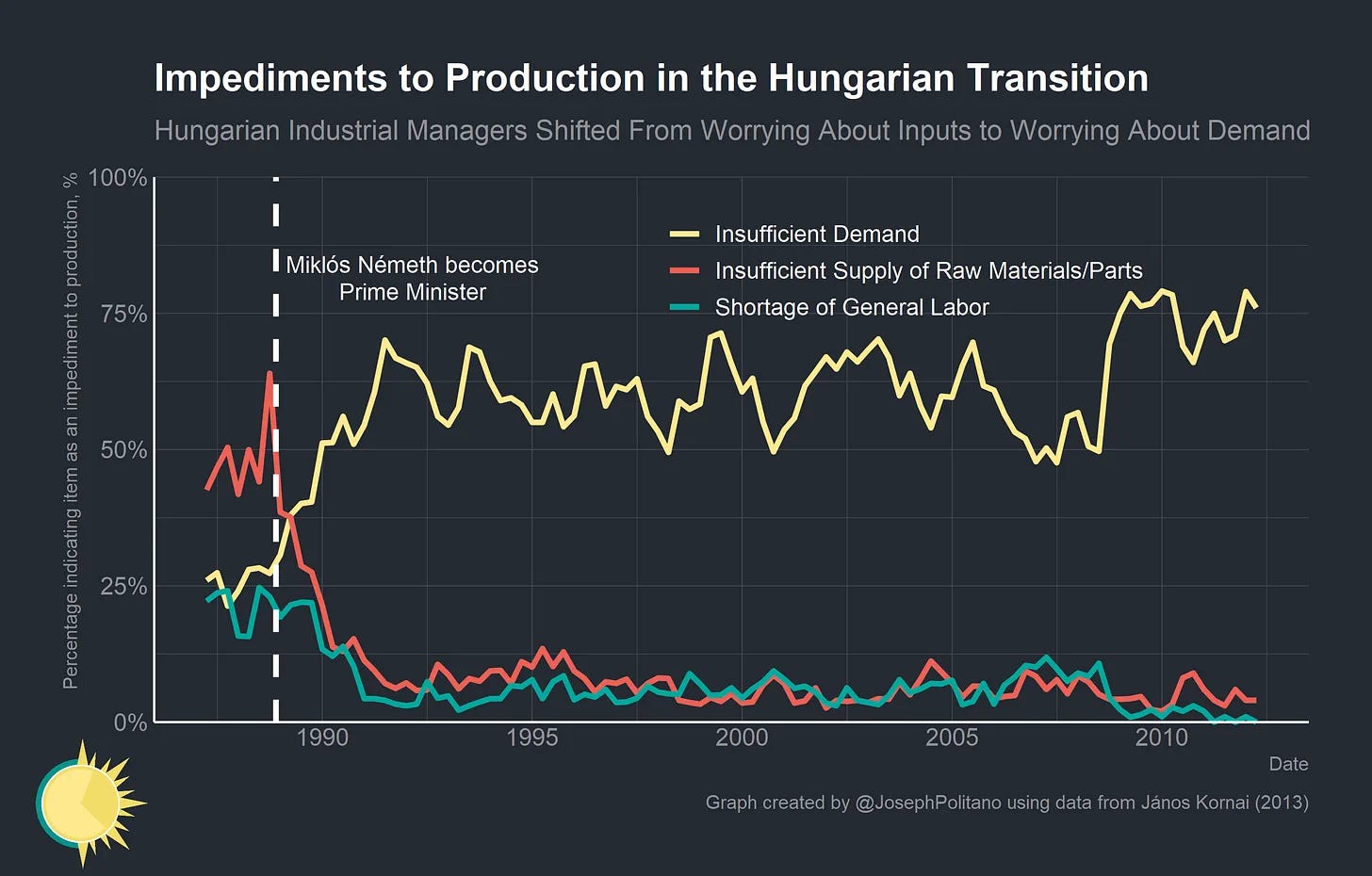

Last year, I wrote about the late Hungarian economist János Kornai, and how his work analyzing the command economies of the Eastern Bloc applied to the myriad of problems that had been plaguing today’s economy. Kornai’s work sought to explain the persistent failures of the Soviet system, in particular the omnipresent shortages that were absent from market economies.

In Kornai’s mind, the answer was more systemic: state ownership of property and the factors of production fundamentally meant that companies were not bounded by profitability or other financial budget constraints. If a firm was unprofitable it was propped up by the state budget, and when no firm is constrained by profitability (and thereby demand) they become instead constrained by the amount of labor and materials they can grab. When everyone tries to grab as much labor and materials as possible, you end up with systemic shortages. By contrast, private ownership of property forces restricts the state’s ability to paper over losses and causes companies to be severely bounded by long-run profitability, so firms in market economies compete on finding demand for their outputs rather than on sourcing their inputs. The soft budget constraint of firms in planned economies leads to a resource-constrained shortage economy, and the hard budget constraint of firms in market economies leads to a demand-constrained surplus economy.

Kornai outlived the Eastern Bloc and got to study its transition into market economies—watching in real-time as firms became and remained almost entirely constrained by demand instead of supply. The global structural economic shift since the start of the pandemic has been the reemergence of those acute shortages that so rarely affect market economies outside wartime—the economy was becoming resource-constrained. It wasn't just that goods and services were rising in price, but that whole swathes of them were simply unobtainable—medical supplies, raw materials, electronic components, energy, labor, logistics, and more. There were unquestionably major hits to supply, but the key shift was structural and partly related to demand. Used car prices shot up because a surge in demand collided with a fall in vehicle manufacturing amidst a shortage of semiconductors, but that shortage of semiconductors was due in part to consumer electronics manufacturers taking up much more of the chip supply to meet their own surge in orders—demand had so overwhelmed the system that companies were fighting to obtain inputs just as much as they were fighting to sell their outputs. The subsequent price increases, and perhaps more importantly price volatility, were a downstream consequence of corporations struggling to manage the global surge in aggregate demand amidst major hits to their supply capacity and the emergent structural shortages of inputs.

The role of monetary policy in this situation was complicated—on the one hand, central banks obviously could not conjure up the food, energy, and other manufactured goods that were in short supply, but on the other hand, endemic global shortages were partially a result of overwhelming demand caused by too-loose monetary policy. To fix it they would need to be skilled and lucky, tightening policy to harden up firms’ budget constraints while hoping that supply-side capacity could return to ease shortages.

That combination of immaculate disinflation from the easing of supply and intentional disinflation from the weakening of demand has played out steadily over the last year and a half—the share of American manufacturers supply-constrained by materials and labor shortages has shrunk as the share demand-constrained by their lack of new orders has grown significantly. If more up-to-date data from the EU is to be believed, the effect has become even more pronounced in recent quarters, with the intensity of supply shortages declining to only slightly above pre-COVID levels.

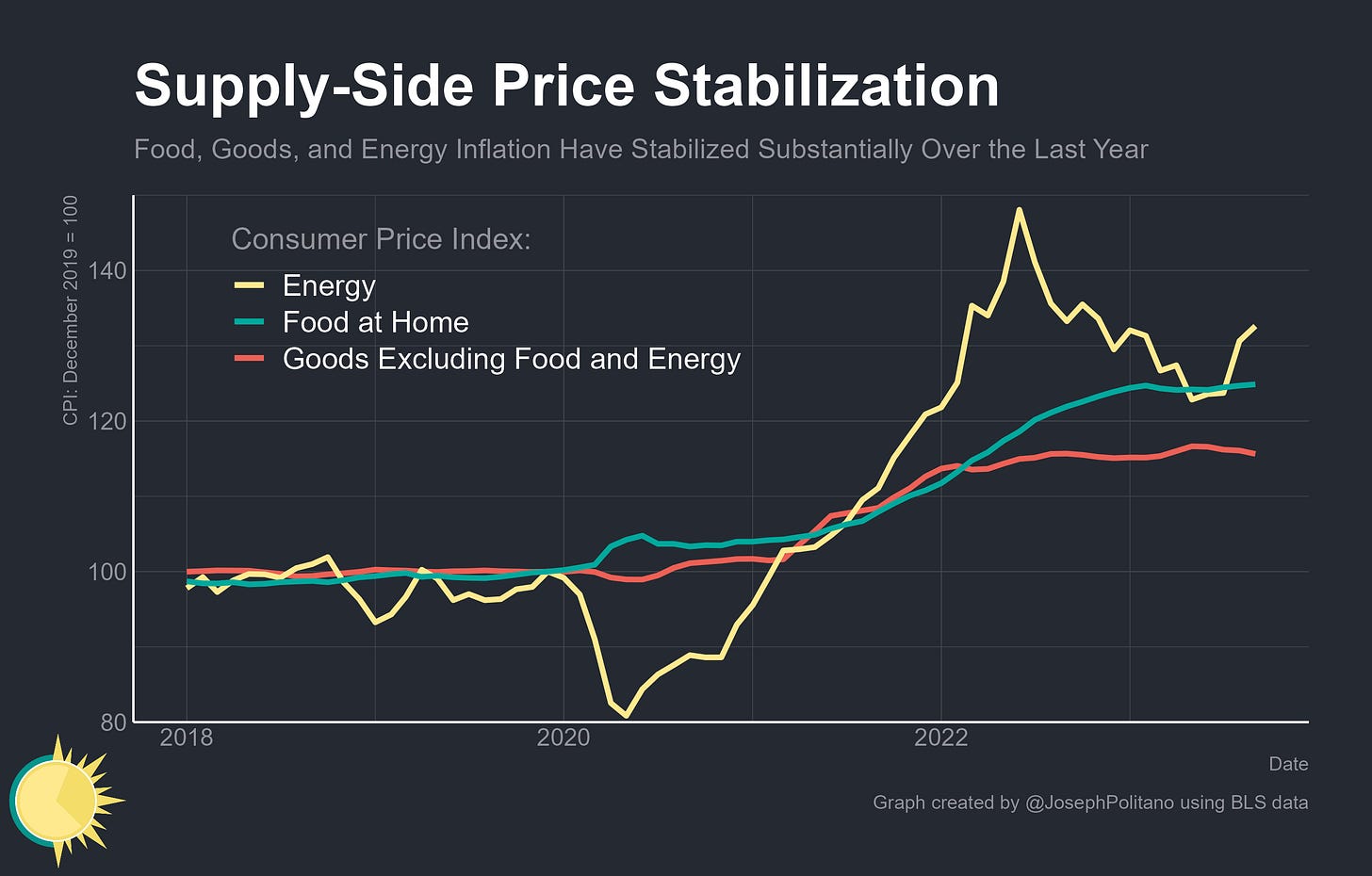

That effect has also led to the significant deceleration—and shifting composition—of American inflation. Year-on-year price growth in core goods has functionally disappeared, dropping to the lowest levels since June 2020, grocery inflation has slowed to the lowest level since June 2021, and energy prices have been essentially flat over the last year. The driving forces behind headline inflation are now overwhelming from housing and labor-intensive services, both of which are cooling alongside aggregate demand. The net effect of the easing supply constraints and tightening of demand constraints has reversed the situation from this time last year—real growth has accelerated even as nominal growth has slowed considerably. The economy is approaching the normal state of surplus that had characterized much of pre-pandemic life.

Fixing the Supply Side

Indeed, over the last year, we have seen relative price stabilization across the food, energy, and manufactured goods sectors whose prices have been dominated by supply-side dynamics. These sectors are resistant to the direct influence of monetary policy—food and energy prices are volatile and supply-driven in normal times with the rise of a shortage economy forcing many core goods into that dynamic—and their stabilization reflects primarily the easing of the supply constraints characteristic of the shortage economy.

That easing of supply constraints has been most pronounced in the advanced manufacturing sectors most affected by pandemic-era shortages. American manufacturers of chemicals, electronics, transportation equipment (cars, planes, etc), and to a lesser extent electrical equipment have seen significant renormalization of their supply chains over the last year and a substantial fall in the share experiencing acute shortages. That’s coincided with the easing of logistics and transportation constraints across a wide variety of modes, with trucking costs falling and transoceanic freight times shortening.

Yet it’s important to highlight just how broad-based the shortages were—while complex advanced manufacturing sectors were hardest-hit, virtually every slice of the economy was impacted to some degree. Likewise, the easing of capacity constraints since late 2022 hasn’t just been in high-tech sectors but spread across industries. Part of the stabilization in grocery prices over the last year came as a result of stabilization in agricultural supply chains—the share of American food manufacturers are now citing material shortages at the lowest level since early 2021.

That broad easing of supply constraints has allowed output to increase across many categories. The archetypical example is in vehicle manufacturing, where output has finally recovered to 2019 levels despite the semiconductor shortage, but this is also true in energy production (the US Energy Information Administration expects households with gas heating to pay $160 less this winter thanks in large part to increased domestic natural gas production) and food production (price stabilization has come in part from a rebound in agricultural output). These are also self-reinforcing effects—improvements in energy production pass through to improvements in vehicle manufacturing which pass through to improvements in logistics systems and so on and so on. The key dynamic is structural and systemic as shortages turn back into surpluses.

Importantly, the share of household spending going towards durable and nondurable goods has been able to remain elevated well above pre-pandemic levels even as supply chains normalize. The reasons for this elevated spending are multifaceted—lower-income consumers who spend a higher share of their money on goods have seen a larger boost in their spending power, work-from-home has allowed households to redirect some services spending into goods, and relative goods prices remain extremely high by pre-pandemic standards—but they underscore how much of the stabilization in prices has come from improvements to supply rather than contractions in demand.

Fixing the Demand Side

Those supply-side improvements represent much of what has allowed real consumption growth to rebound from its 2022 lows amidst declining inflation. In his analysis breaking down the drivers of recent disinflation, Mike Konczal saw that among consumer spending components with decelerating prices, 87% of core goods and 66% of core services saw supply-side expansion over the last year. Yet the key dynamic is that nominal growth, the fundamental long-run driver of price growth, has slowed down even as real growth increased—in other words, demand has cooled as supply has recovered, and both are contributing to the normalization of inflation.

Nominal gross labor income, the aggregate sum of wages and salaries in the economy and a central driver of consumer demand, also continues to slow down toward the rates seen in pre-pandemic years. This slowdown has helped drive the ongoing deceleration in prices for cyclical, demand-driven services including housing and labor-intensive services even as overall employment levels remain high.

Companies are also feeling the ongoing slowdown in spending and demand pressures—a rising share of firms are reporting abnormally low sales levels (although cognitive biases make it rare for owners to ever report average or abnormally high sales levels on net). On a size-weighted basis, they now report sales levels 5.1% below normal, the lowest reading since the beginning of 2021.

These shifts have also brought the expected impact of labor and nonlabor costs on future price increases back down to the lowest levels since the start of the inflation surge in late 2021. Importantly, the expected impact of sales growth has returned to positive levels after the worrying drop in 2022—even as businesses feel the effects of slowing demand, they are becoming more confident they can avoid the kind of sales collapse characteristic of a recession.

The easing of supply constraints combined with the slowdown in demand and spending growth has steadily lowered firms’ experienced and expected inflation. Companies reported that their unit costs had risen 3.2% over the last year, down from the 4.4% reported last summer, but more importantly, their year-ahead expected inflation declined from a ten-year high of 3.8% to 2.4%. Businesses’ long-run inflation expectations have nearly completely re-anchored, with companies expecting just as much inflation over the next 5-10 years as they did in late 2018.

Conclusions

When I wrote about Kornai last year, I concluded by saying this:

Kornai's theories were mostly about the structural long run tendencies of economic systems, with acknowledgments that market economies can and did occasionally encounter short-term periods of acute shortage, especially surrounding shocks like pandemics or wars. The long run tendency is still towards surplus not shortage, so barring fundamental shifts in the nature of the global economy supply constraints should eventually abate.

But the period we're entering will require a hardening of global budget constraints in order to end the shortage economy. Few expect the transition back to normal surplus economies to simply occur naturally any more, and central banks are focused on ensuring that shortages don't morph into runaway price increases. How hard budget constraints must get and how quickly economies can structurally renormalize remains the biggest open question in today's global economy.

Since then, a large amount of structural renormalization has occurred across the globe as market economies move towards their long-run tendency of surplus. Meanwhile, budget constraints haven’t had to harden significantly—financial conditions aren’t meaningfully much tighter than they were this last time last year, if anything they’re a tad looser. That powerful combination is what has allowed optimism and economic expectations to improve so much over the last year—and is a large part of why the Fed feels more confident in keeping rates “higher for longer.”