New Zealand's Building Boom—And What the World Must Learn From It

New Zealand's Broad Upzonings Have Led to a Housing Construction Boom That is Increasing Affordability. The World Should Copy Their Model.

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 40,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

New Zealand has a horrendous, long-standing housing shortage—roughly a quarter of Kiwis are cost-burdened (defined as spending more than 40% of their income on rent or mortgage payments), the highest rate among all OECD countries. The vast majority of the archipelago’s housing stock is low-density—more than 80% of residents live in detached single-family homes, 20 percentage points higher than even in the highly suburbanized United States. Auckland, New Zealand’s largest city, has been consistently rated as one of the most expensive places on earth, with home prices significantly outpacing household incomes.

This story should sound familiar to most Americans, and indeed to people across the world who face increasingly dire housing affordability crises in their countries and cities. Many will blame those housing shortages on zoning restrictions and exclusionary planning rules that prevent sufficient housing construction—in the US, most residential areas are designated exclusively for large, sprawling single-family homes, even within major cities, and local governments often make discretionary case-by-case permitting decisions in an institutional arrangement that gives existing residents significant veto power over new housing. Theoretically, if rules were changed to allow taller and denser developments on desirable land—a process known as upzoning—housing production would increase and affordability would improve.

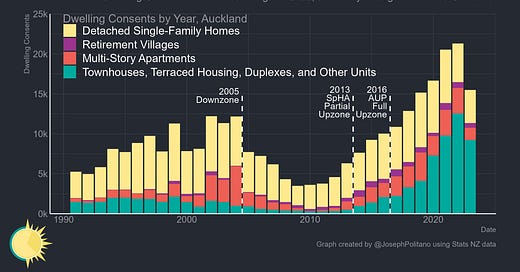

The difference is that Auckland has actually put that theory to practice—the 2016 Auckland Unitary Plan (AUP) upzoned 3/4 of the city’s residential land to legalize townhouses, terraced homes, or multi-story apartments in areas that previously only allowed detached single-family homes, helping to reverse decades of successive downzonings that had occurred as recently as 2005. This makes Auckland perhaps the largest real-life experiment of what broad-based upzoning can achieve in an expensive, supply-constrained city—and in the 7 years since the implementation of the AUP, residential construction has skyrocketed. The total number of housing permits issued smashed previous records, while permits for the multi-unit attached housing projects legalized in the AUP went from only a small percentage of overall construction activity to the city’s dominant source of new housing.

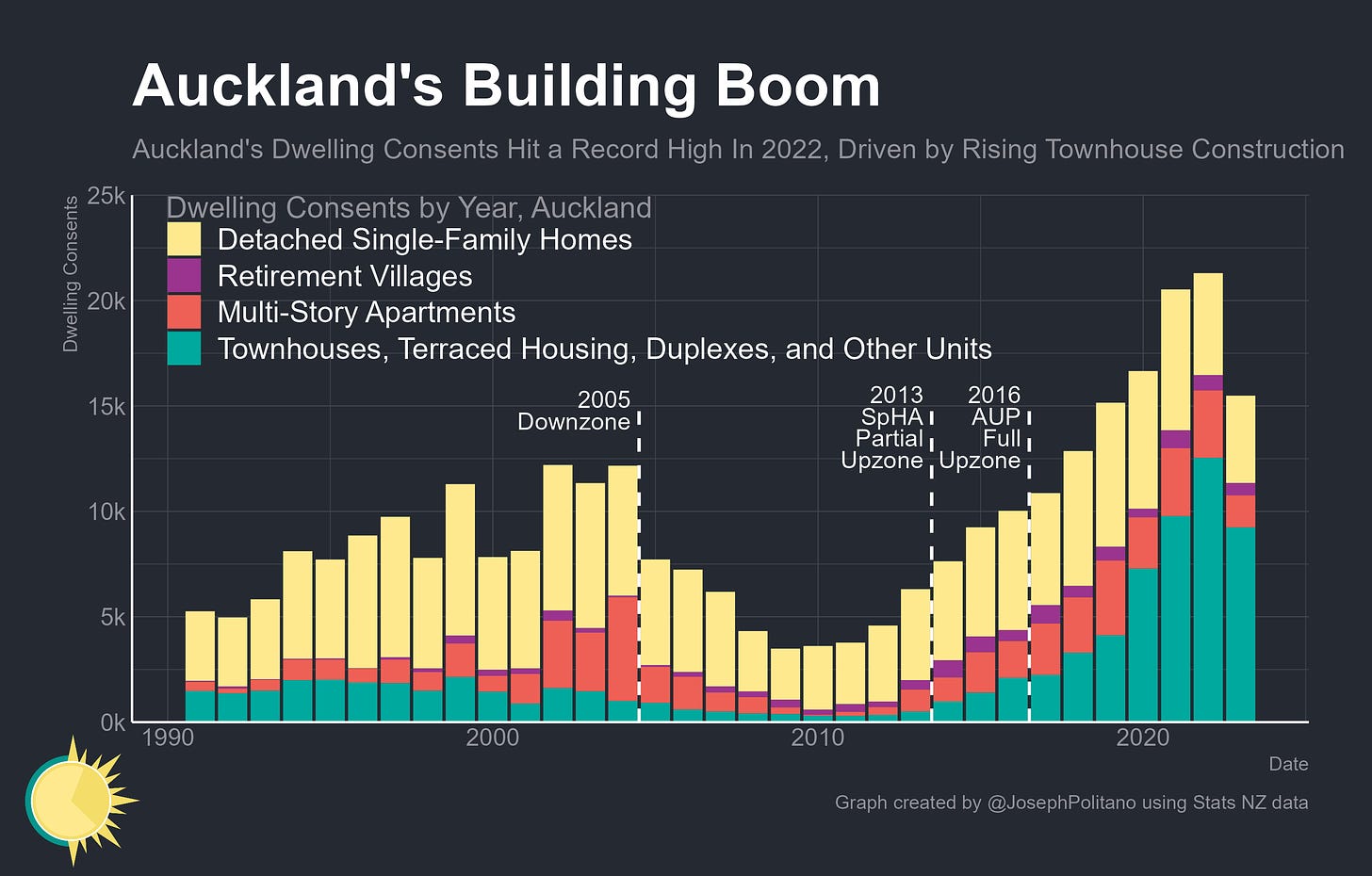

In fact, upzonings in Auckland and elsewhere in New Zealand have set off a massive construction boom throughout the entire archipelago. In 2023, New Zealand (population: 5.2M) permitted 37k housing units, more than the San Francisco and Los Angeles metro areas combined (population: 17.3M). Auckland, a city of only 1.7M, permitted 15k units last year—while preliminary data shows the 5 boroughs of New York City (population: 8.3M) permitted a meager 9.2k units by comparison. In total, New Zealand permitted 9.7 new housing units per 1000 residents in 2022, a 45-year-high that was nearly double the rates seen in the US.

The rise in housing construction has significantly constrained rent growth, improved housing affordability, and boosted the nation’s economy—which is why New Zealand has doubled down on the strategy. The central government has pushed for even broader nationwide upzonings since the start of the pandemic, and cities throughout the country are increasingly copying Auckland’s land-use liberalization policies. The US—and countries across the world—must learn from New Zealand’s success if they hope to address their own housing shortages.

Yes in My New Zealand

New Zealand, like many countries, experienced a sustained housing construction boom that stretched from the end of the Second World War to the inflationary period of the mid-1970s. Yet after the end of the postwar housing boom, the passing of the 1977 Town and Country Planning Act, and the scaleback of public-sector construction, total homebuilding was constrained for nearly four decades before falling off a cliff in the 2008 recession. So the nation’s housing market was already chronically undersupplied when a magnitude 6.2 earthquake struck the city of Christchurch in 2011.

More than 180 people passed, and thousands more were displaced or made homeless as a result of ensuing property destruction and land deformation. Entire neighborhoods became red zones deemed unsafe for human habitation, forcing the government to buy out homeowners and demolish thousands of residential buildings. Rents shot up as families suddenly had to find new places to live, and the housing crisis had rapidly transformed into a housing emergency.

As part of reconstruction efforts in 2012 and 2013, the central government made Christchurch and surrounding areas open up more greenfield sites for residential development, permit denser infill of existing suburbs, and reorganize large sections of downtown to alleviate the housing crisis. The region was essentially rezoned for decades of housing capacity growth all at once, which resulted in a significant construction boom over the next decade. In an attempt to ease the wider housing shortage, the central government also created Special Housing Areas throughout the country where new developments were fast-tracked if they set aside some units for income-restricted affordable housing.

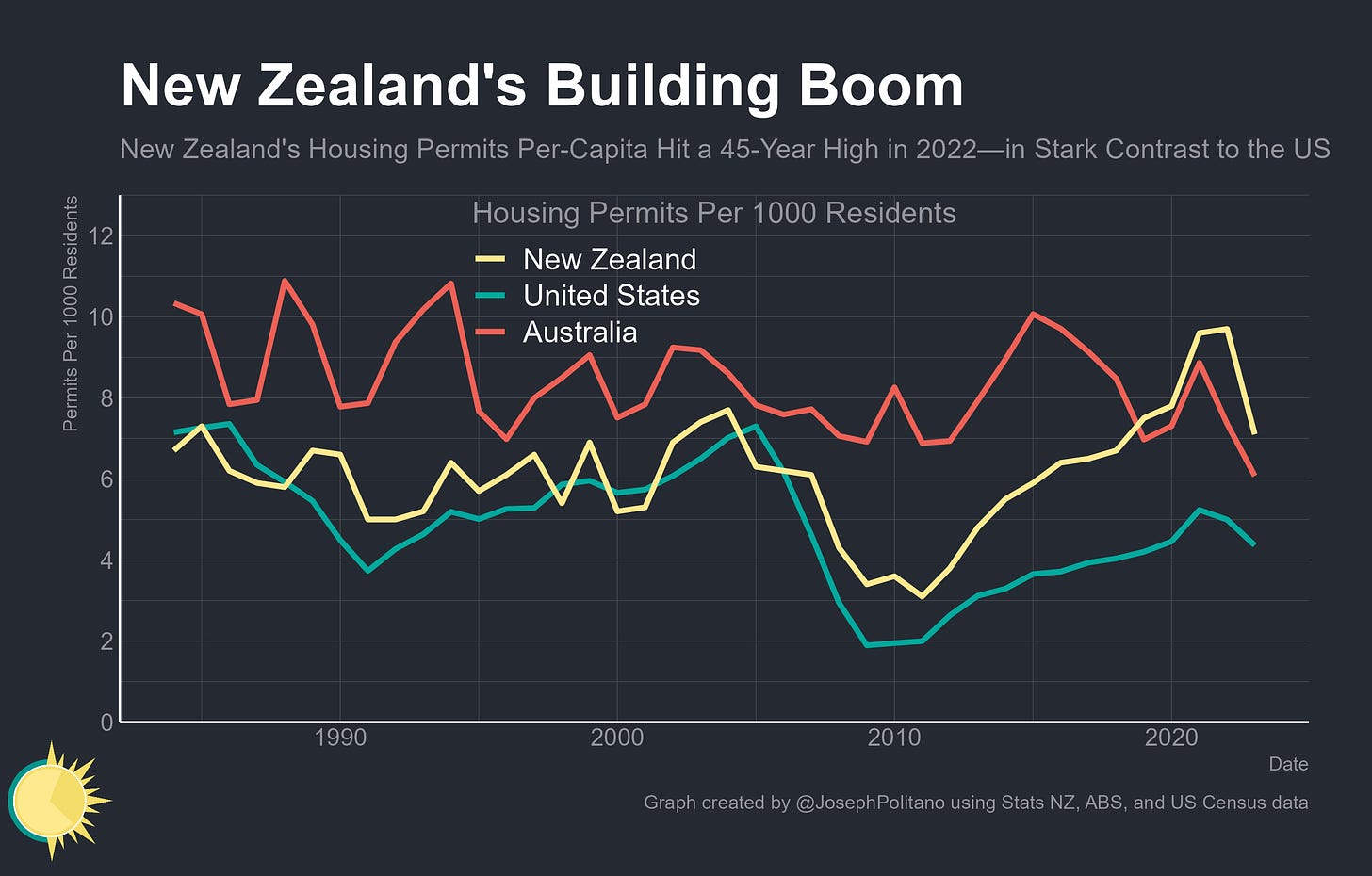

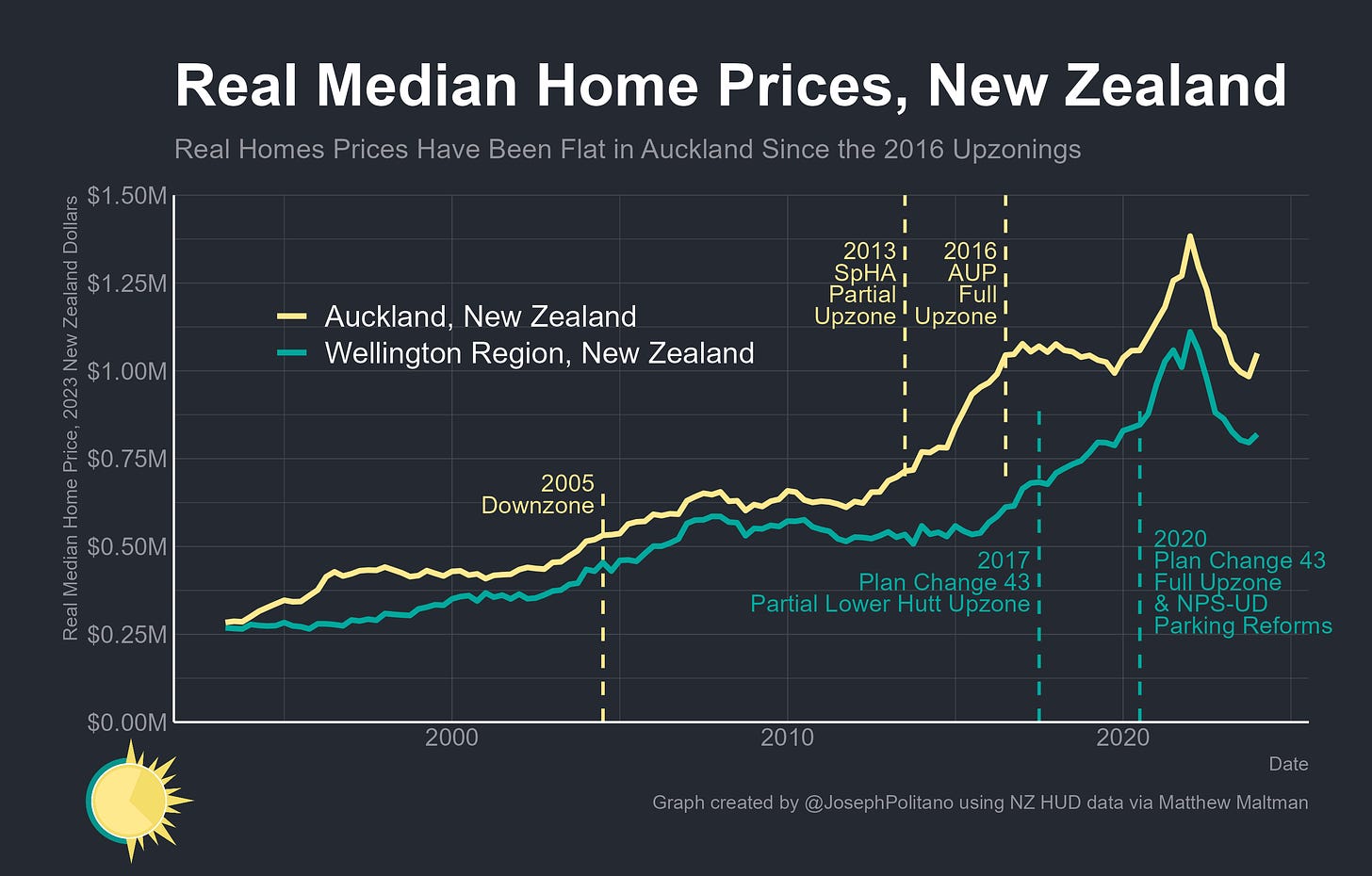

At the same time as the Special Housing Area rollout, Auckland began drawing up the plans for its own mass upzoning. An ambitious proposal was rolled out in 2013 and preliminary implementation began soon after, but rapid housing price increases and pressure from the central government to address the crisis resulted in a final plan that was even bolder. By the time of the full implementation of the AUP in 2016, the city would be rezoned to have a theoretical capacity 2.5 times the size of its current population. Construction activity rapidly rose after upzoning, with per-capita permitting reaching the highest levels in modern history in 2020, breaking the 2020 record in 2021, and then breaking the 2021 record again in 2022. Contrast that with Wellington, New Zealand’s capital city, where a lack of upzoning led per-capita permitting activity to peak below 7 units per thousand residents in 2019.

The 2016 upzoning not only increased the quantity of housing supplied throughout Auckland, but it also heavily shifted the geographic structure of the city’s development patterns. Although much of the land closest to the Central Business District avoided upzoning, many of the city’s inner-ring suburbs saw plenty of infill construction activity that drew demand away from the outer suburbs and closer to the CBD on net. Construction also got closer to job centers and rapid-transit stations, indicating that the upzoning helped unlock dense development in high-demand areas in ways that improved the city’s overall efficiency and accessibility.

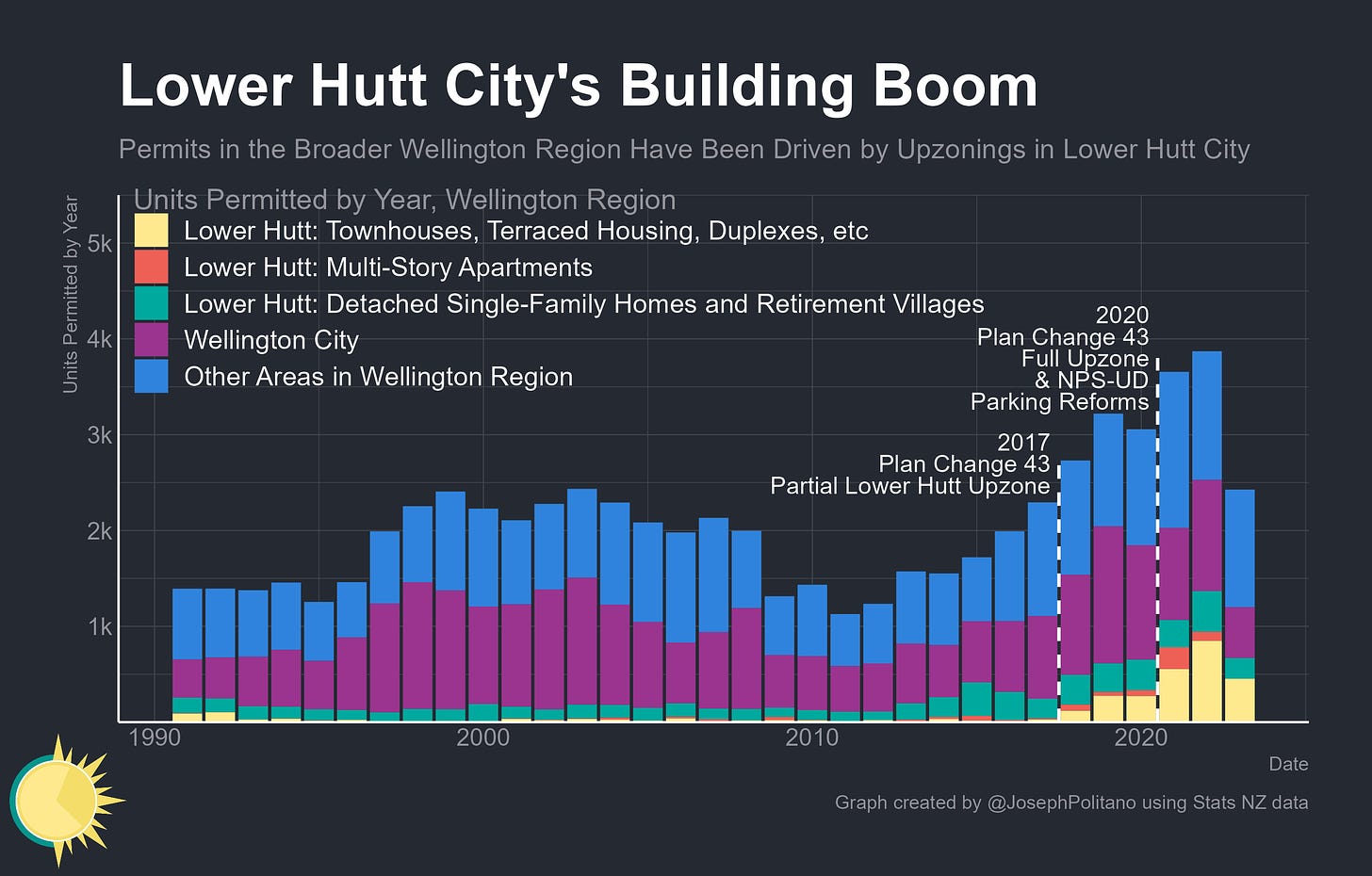

The success of Auckland’s upzoning then spurred policy reform elsewhere in New Zealand—for example, Lower Hutt, a city of 114k in the Wellington region, passed significant upzonings to address their affordability crisis from 2017 onward. Plan Change 43 created new mixed-use and medium-density residential areas while allowing greater density in many existing residential zones and Plan Change 39 relaxed the city’s parking requirements before they were completely removed in 2020. The upzonings caused a historically massive construction boom—in 2022 Lower Hutt was responsible for 1/3 of all construction in the region, more than Wellington city itself, with 2/3 of new units being townhouses or apartments.

The cumulative effect of these upzonings was enough to bring New Zealand’s per-capita permitting to a 45-year high—and Auckland went from regularly trailing nationwide construction levels to leading it. Nationally, the strategy expanded even further when the National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD), which abolished parking requirements in major cities and required 6-story buildings be allowed near downtowns and rapid transit stops, passed in 2020 and came into force for many cities this summer. It was swiftly followed by Medium Density Residential Standards (MDRS), which would have allowed 3-story triplexes by right in essentially all New Zealand suburbs but remains in limbo and may be made optional by the current government. Still, that leaves Auckland (and NZ more broadly) as one of the most successful cases of broad upzoning in recent world history.

What did Upzoning Achieve?

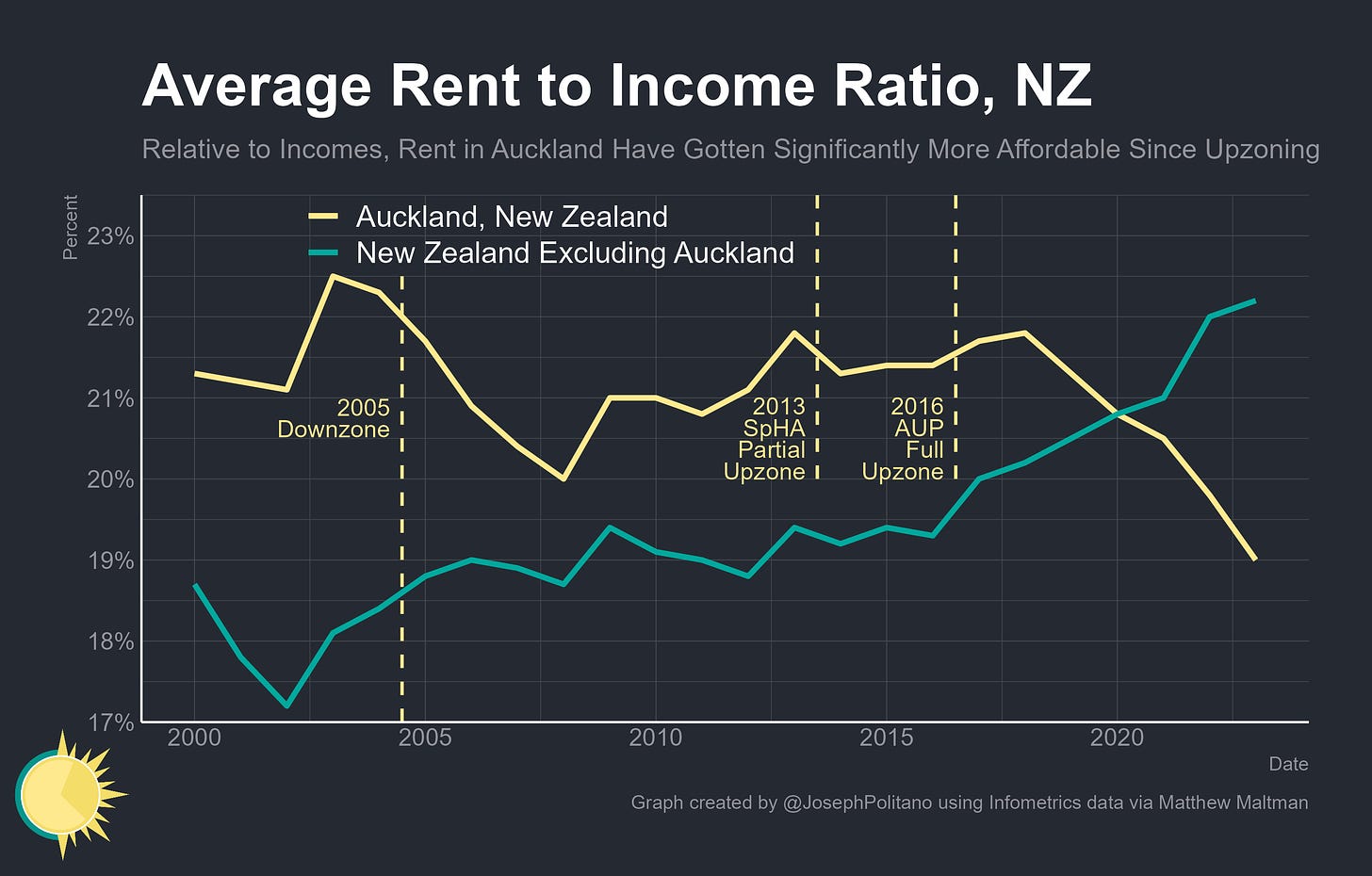

So over the last decade-plus, what has been the economic effect of these upzonings in Auckland and other parts of New Zealand? The best evidence comes from a series of academic papers by Professor Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy at the University of Auckland and comprehensive data tracking done by Matthew Maltman at Australia’s E61 Institute. Despite some early back-and-forth academic quibbles, the evidence is overwhelmingly clear that upzonings have significantly increased housing production—the AUP is estimated to have created more than 43k extra housing units from 2016-2022, while the Lower Hutt upzonings increased total Wellington region housing starts by 12-17%. That, in turn, has significantly improved housing affordability—rent-to-income ratios in Auckland have significantly declined even as they have steadily risen elsewhere in New Zealand.

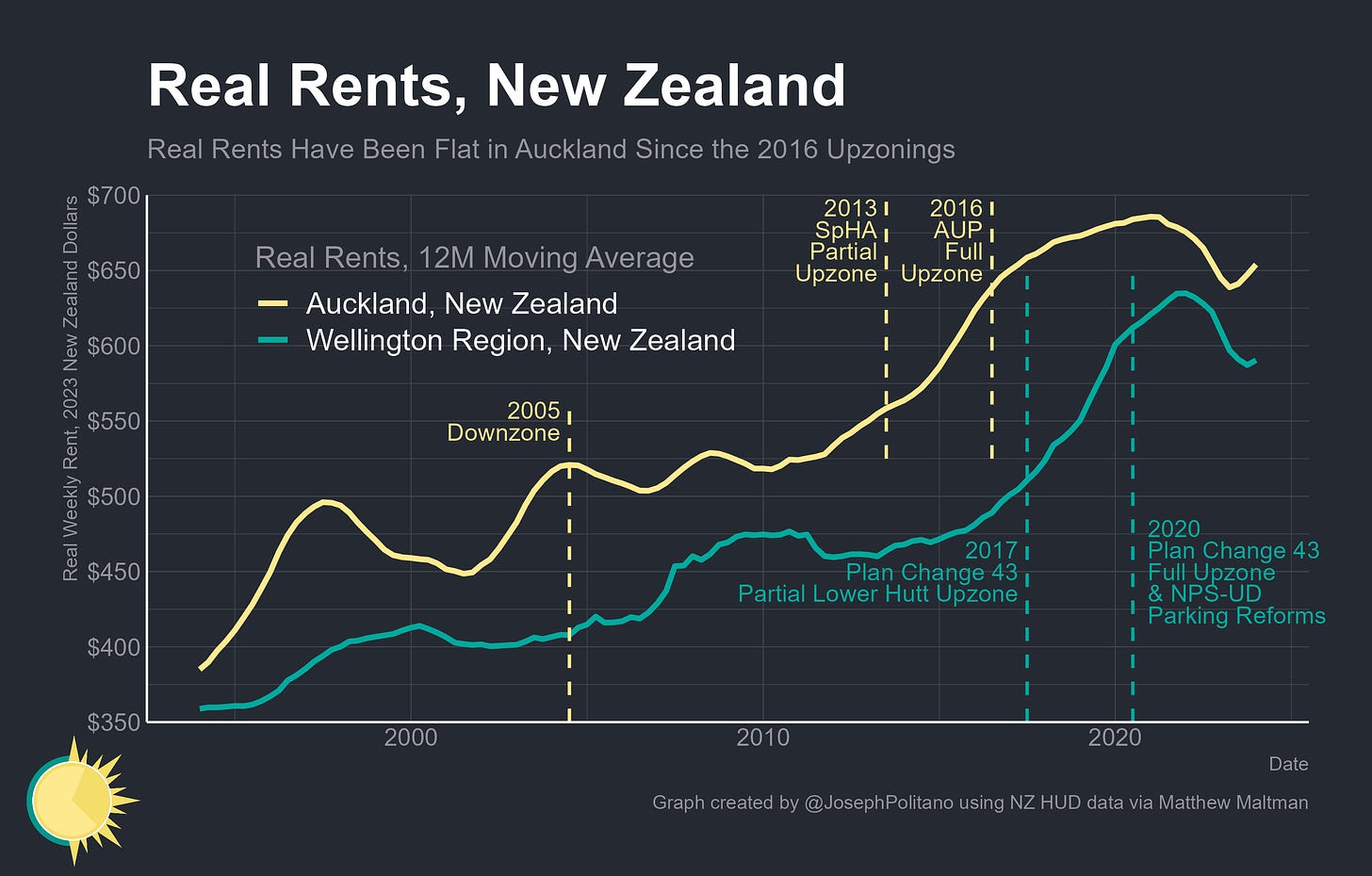

In fact, after adjusting for inflation rents in Auckland have been essentially flat since the 2016 AUP—and Greenaway-McGrevy estimates that 2-bedroom apartment rents are roughly 26-33% lower than they would be in the absence of upzonings. That easing of rent pressures was felt most at the lower end of the price distribution—real rents of Auckland’s cheaper apartments fell faster than the real rents of its median apartment. From 2016-2020 rents in the Wellington region grew much faster than rents in Auckland, but even they have declined amid the steady rise of construction in Lower Hutt since the start of the pandemic.

Real home prices have also been constrained by the upzonings—after rising steadily for years, median sales prices in Auckland leveled off in 2016 and remain at those levels even 8 years later. Real prices in the Wellington region increased up until the early pandemic, but remain roughly at 2019 levels today.

The AUP also represents an instructive case study for the modern housing discourse that pits upzoning as a market-based solution in opposition to direct government action like rent control or public housing. New Zealand’s experience shows the two approaches are complementary, not contradictory—a post-2017 political push for more state housing construction, combined with the upzonings in Auckland and elsewhere in New Zealand, has driven public housing permits to record highs. While the government came nowhere near meeting its ambitious national public housing goals, Greenaway-McGrevy estimates that AUP reforms nearly tripled public housing construction in Auckland. That construction boom has been especially important for the indigenous Māori, who make up 40% of public housing residents, and Pacific peoples indigenous to other islands, who make up another quarter of residents.

More broadly, the upzonings have been so large as to deliver widespread macroeconomic benefits to New Zealand over the last decade. Residential fixed investment as a share of GDP has been at or near record levels over the last two years—higher than in Australia and double the share seen in the US. Construction activity in Auckland alone has gone from 1.56% of nationwide GDP in 2012 to 2.67% in 2021, and Auckland’s per-capita GDP has gone from being 6% above the national average in 2012 to 13.8% above it in 2022.

Plus, it has been a boon for the country’s construction employment—the total number of people working in the construction industry has gone from 167k in 2012 to 309k in 2023, while the number of construction workers in Auckland alone has doubled from 51k to 107k. Compare that to the US, where overall construction employment had only recovered to its pre-2008 peak in 2022. It’s a key reminder that planning and land-use policies can have major economic spillovers on both investment and labor market outcomes.

Conclusions

Upzoning’s successes throughout New Zealand are now shifting the political tides even in once-NIMBY-strongholds like Wellington—the city’s district plan passed this week is on par with or perhaps even more radical than Auckland’s 2016 upzoning. Amendments that heavily expanded high-density zoning, removed minimum front and side setbacks, and ended redevelopment bans in large chunks of downtown all passed and are now awaiting final signoff from the housing minister. It’s a story about how cross-partisan policymaking, local activism, and national governments with the will to overcome NIMBYism can make real progress on alleviating even the most brutal of housing shortages.

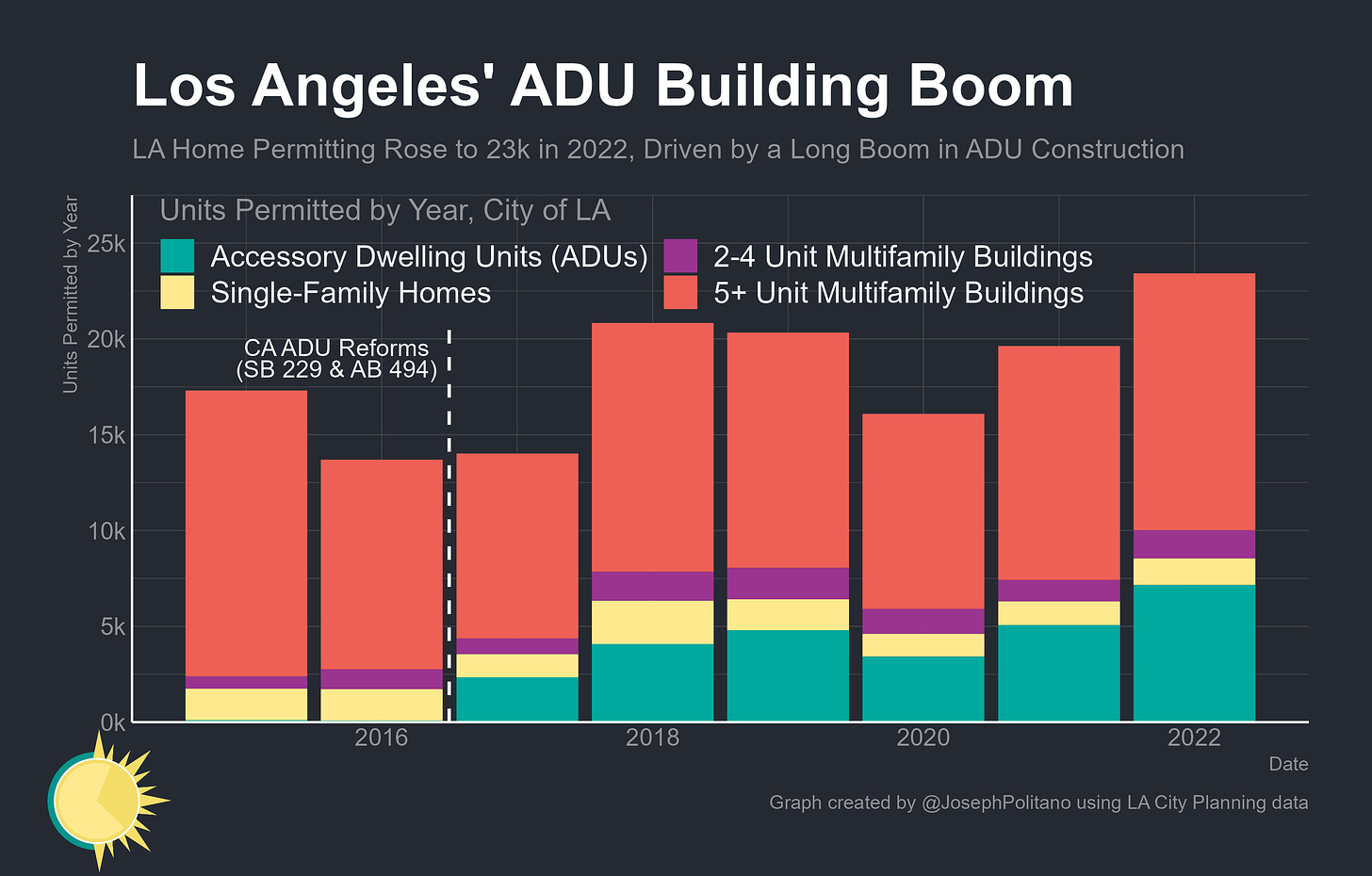

There are some examples of the US following these successful models—take Los Angeles’ boom in Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs). Reforms passed by the state of California in 2017 that removed parking requirements near transit, eliminated separate utility connection fees, and streamlined approval processes turned ADUs from a functionally nonexistent source of housing construction to 1/3 of all new units in the city. That’s both a testament to the success of ADU reforms and an indictment of the longstanding failure to build sufficient traditional housing units. More importantly, it’s illustrative of just how much can be unlocked in supply-constrained housing market through meaningful permitting and land use changes. But incidents of American cities reforming away from restrictive and exclusionary planning regimes are still few and far between—so if places like Los Angeles, California, and the US more broadly want to make real progress in tackling their housing shortages, they should look to New Zealand for inspiration.

Excellent article. The problem of unaffordable housing is simple to solve: repeal government regulations and let builders build.

Excellent article. I used to live in Wellington 30 years ago when it was cheap, grungy and fun. Now it’s expensive but it’s amazing how few new buildings have appeared since then. Hopefully the new district plan will begin to address the chronic housing shortage.