The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

In yesterday’s jobs report, non-farm payrolls rose by 467,000—seemingly defying the expectations of many economists and professional forecasters who had predicted a moderate decline in business payrolls. Higher-frequency data from before yesterday suggested a drop in employment caused by the Omicron variant—ADP (a payroll services provider) showed employment shrinking by 301,000 in January and initial unemployment claims spiked in the first week of the month. The strong employment print was therefore a welcome surprise, and some commentators touted the data as proof that the Omicron variant had little impact on the economic recovery.

On the contrary, a deeper analysis of the data shows that Omicron had a significant negative impact on employment and that most of the perceived employment growth in January is the result of methodological quirks and latent pre-Omicron strength. It is likely that employment shrunk between December and January as Omicron swept through the country. The good news is that by almost all metrics employment performed better throughout 2021 than estimates showed in December, but it is still important to note that the month-on-month employment change between December and January was likely negative.

Understanding why requires a technical analysis of the methodological specifics of the BLS’s employment situation report. It also requires digging deeper into the data in order to analyze COVID’s impact on the labor market. Finally, the revisions to prior data demands a reexamination of employment growth throughout 2021. This likely represents the most complicated jobs report in living memory, and it is important to pick it apart in order to fully understand the situation.

The Household Survey

First, some background. The employment situation—colloquially known as the jobs report—is actually made up of two separate programs. The first is the Current Employment Statistics (CES) program—otherwise known as the establishment survey—and the second is the Current Population Survey (CPS)—otherwise known as the household survey. The establishment survey collects data from businesses on their workers and the household survey collects data from households. The two survey are then welded together to form the jobs report. For example, the headline payrolls number (the 476,000 jobs added in this case) comes from the establishment survey while the headline unemployment rate (4% in this case) comes from the household survey.

The household survey has generally been the better real-time indicator throughout the pandemic, as the establishment survey has lagged behind and subsequently been brought closer in line with the household survey by revisions. Much of the strength in the establishment survey and growth in payrolls is likely driven by data “catching up” to the household survey—but more on that later. The household survey looked extremely strong this month, with the employment level rising by 1.2 million and the labor force participation rate increasing by 0.3%. However, this was an illusion driven by updates to the annual population estimates:

Another quirk in January’s report was revisions to reflect updated population estimates used in the household survey. Had it not been for those controls, the number of employed Americans would have dropped by 272,000, according to the Labor Department.

By the same token, the participation rate—the share of the population that is working or looking for work—would have been unchanged from December, rather than the registered 0.3 percentage point increase.

To be clear: the updated employment levels and labor force participation rates are accurate statistics, and they better reflect the true state of the labor market than the December data. However, the BLS does not update prior-year data based on the new population estimates, only the January and onwards data. What this means is that the December 2021 data was systematically underestimating employment and that the 2021 employment numbers were better than first published. However, the headline change in employment, labor force participation, and unemployment between December and January is distorted by the incorporation of these new estimates and therefore not as good as it initially seems. Again, the US actually saw a 272,000 decrease in employment levels that was hidden by the updated population data.

What, specifically, did the population estimates change? Firstly, it significantly increased the employment-population ratio and labor force participation for older workers. An additional 0.6% of people 55 and older in employed and an additional 0.7% of people 55 and older were participating in the labor force according to the new population estimates. This explains the entire rise in employment and labor force participation for older workers in this month’s report. Just as important, however, was the re-estimating of the age demographic breakdown.

Although the total unemployment rate was unaffected, the employment-population ratio and labor force participation rate were each increased by 0.3 percentage point. This was mostly due to an increase in the size of the population in age groups that participate in the labor force at high rates (those ages 35 to 64) and a large decrease in the size of the population age 65 and older, which participates at a low rate.

The population estimates for people aged 16-54 were revised upwards by about 1.7 million while the population estimates for people aged 55 and older were revised downwards by about 750,000. Since younger people are more likely to be employed or participate in the labor force than older people, this increases aggregate employment and labor force participation rates. These changes are largely due to blended 2020 population base drawn mostly from the 2020 Census. If you are interested in a complete breakdown of the impacts of the population estimates the BLS provides a helpful guide here, but those are the important takeaways.

Incidentally, this is part of the reason why it is important to focus on the prime age employment-population ratio as the central labor market indicator. Prime age population and employment estimates are more reliable, less volatile, and less affected by structural forces like an aging population. The population estimates adjusted the prime age employment-population ratio up 0.1%, so there was actually no movement between January and December once the population estimates are discounted. Omicron is likely responsible for the slowdown in employment growth over the last month.

The Omicron variant is extremely virulent and infected a large number of Americans in January, dramatically affecting the labor market. A record 3.6 million workers were employed but out of work due to sickness in January and a record 4.2 million people were working part-time due to illness. The number of Americans employed but not at work due to childcare issues also jumped nearly 50% (from 50,000 to 72,000), although that data is particularly noisy so I would not read too much into it.

More critically, the number of people unable to work because their employer closed or lost business due to COVID spiked in January. Although the total number of workers affected by COVID business closures is extremely low compared to this time in 2021, it represents the first major reversal in more than a year. Nearly twice as many Americans were out of work due to COVID in January when compared with December.

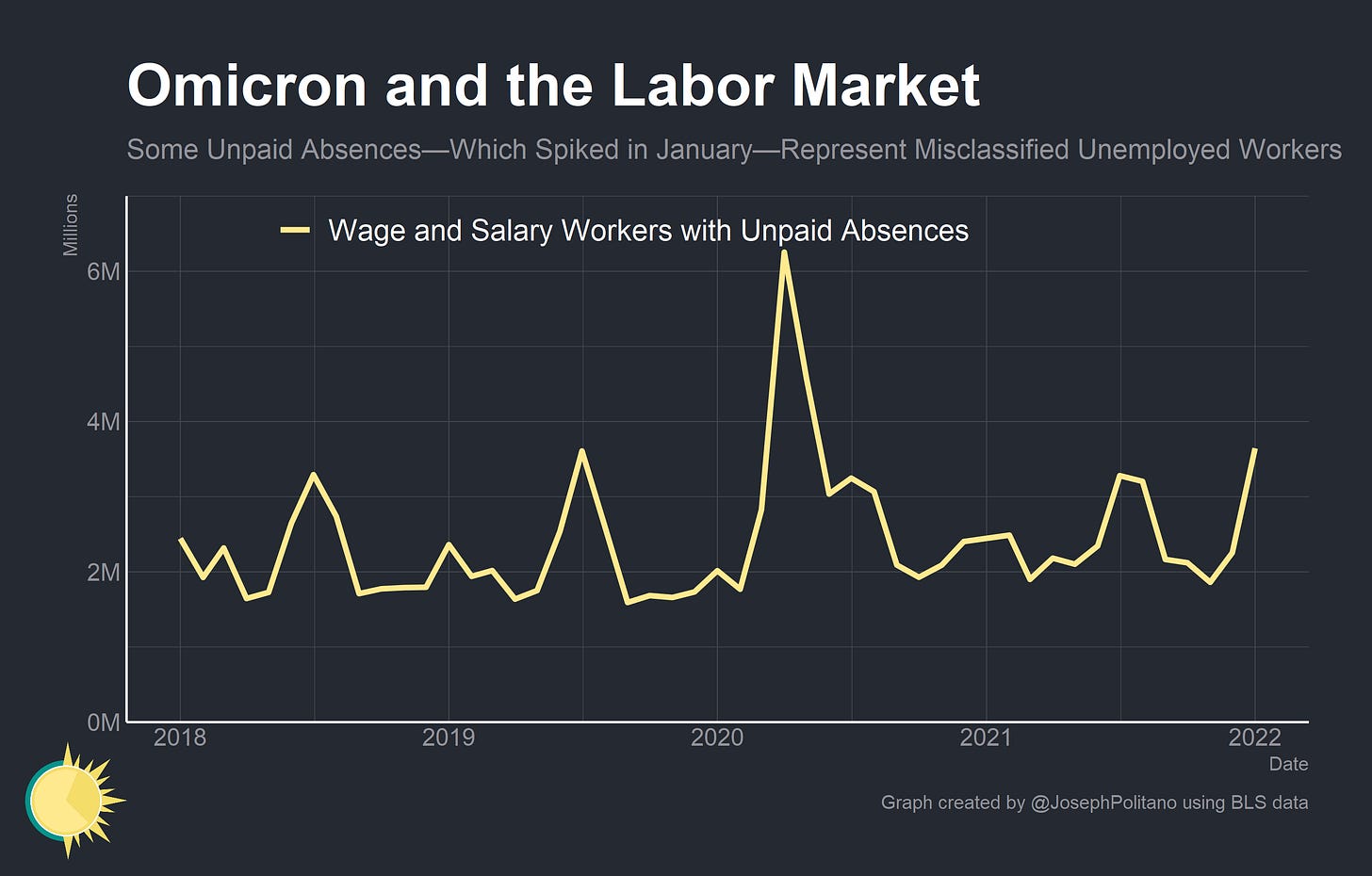

Finally, there is good reason to believe the data systematically undercounted the unemployed in January. The household survey ran into a serious problem early in the pandemic when many workers misclassified themselves as “employed but not at work” when they should have been classified as “unemployed.” The issue mostly died down by mid-2020 though—until Omicron hit. In January we saw a 1.4 million increase in workers who classified themselves as employed but on an unpaid absence. Most of these workers are likely taking unpaid sick leave or unpaid time off to take care of a family member, but coupled with the increase in pandemic-induced business layoffs it suggests some were misclassified unemployed workers. The BLS’s upper-bound estimate for the number of misclassified unemployed workers in December was 195,000, but that same methodology would suggest an upper-bound estimate of 645,000 for January. No matter which way you slice it, it is clear that Omicron had a material negative impact on the labor market recovery.

The Establishment Survey

As mentioned earlier, payrolls did increase by 467,000 from December to January as measured by the establishment survey. In addition, regular revisions to the November and December numbers added another 709,000 job gains. Benchmark revisions—where the BLS incorporates extremely comprehensive data sources to update the year’s establishment survey—increased total 2021 payroll growth by 217,000. All of that is a complicated way to say that the establishment survey showed strong growth and significant gains, especially in revisions.

Part of this reflects lower layoffs at a time of year when layoffs are usually very high, but part of it reflects the establishment survey catching up to the household survey. Throughout 2021, the establishment survey has seemingly lagged behind the household survey with growth in employment only being reflected in payrolls after revisions. In fact, with the updated population estimates, the establishment survey actually fell marginally farther behind the household survey in terms of employment levels.

There are two other important things to note about the establishment survey. First, changes to the seasonal adjustment calculations essentially reduced the summer job gains and increased winter job gains by an offsetting amount. Second, the benchmark revisions significantly changed the composition of employment levels by industry.

For example, the benchmark revision lowered aggregate leisure and hospitality payrolls by approximately 600,000 while smoothing out the growth rate through the updated seasonal adjustment. This leaves leisure and hospitality as the major laggard in the labor market recovery, with a shortfall of 1.7 million jobs compared to the pre-pandemic level.

On the flipside, revisions added 240,000 jobs to the transportation and warehousing industry. This brings employment in the sector to a record 6.3 million in January as Americans continue to spend a disproportionate amount of money on goods. Other notable industries with revisions include temporary help services (revised up 220,000), information (revised up 120,000), and state government education (revised up 170,000).

Conclusions

The complicated January jobs report should serve two lessons. The first is that it is always a bad idea to uncritically focus on one jobs report in isolation. It’s important to dig under the headlines and understand the methodology and nuances of the data in question. Knowing the size of payroll gains doesn’t tell you enough alone—you have to look at what industries, trends, and data choices are driving the payroll gains in order to develop an informed understanding of the situation.

The second lesson is that COVID still has a major impact on the labor market and is hampering the economic recovery. People touting this jobs report as evidence that the economy can comfortably ignore the virus were misled by the headline numbers and failed to take full account of Omicron’s significant negative impact on workers. At least 55,000 people passed away due to the pandemic in December, the highest number since before vaccines were widely available. COVID still remains the central obstacle to a full economic recovery, and policies that bring us closer to the end of the pandemic will be critical moving forward.

On the brighter side, the US is still poised for possible large gains in employment growth over the next few months. Firms are clearly working to retain workers in spite of the pandemic, which could lead to fewer-than-expected layoffs and subsequent rises in employment numbers. Omicron’s impact will likely be shorter and less severe thanks to higher vaccination rates, although the threat of new variants still persists. In other words, the virus remains the boss and good public health policy will be critical in ensuring good economic outcomes.

Just shows how Covid has made inferences much harder to make. This is also true in many other instances, prices for example. But one thing I´m sure of. Being uncomfortable with the recent rise in inflation was a small price to pay to avoid a "deadly" depression!

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/a-21st-century-us-monetary-story

I too found this very interesting and wondered whether there are a couple of international comparisons you might look at. First, the (new) payroll data in the UK - based on tax data has also been subject to major revisions. But in the opposite direction to the UK. I was wondering if the different features of the two systems might help explain this. In US I was wondering how layoffs (not a featuer of UK) are treated and whether lags in workers being taken back on might be a factor. In UK it is likely to work in opposite direction. There is 20% imputation in the RTI payroll data. I suspect, therefore, that employment in previous month is rolled forward until actual information - including outflows - are brought in in future months.

The other feature is the UK household data which is also showing odd signs. The most common explanation is that population estimates are over-stated as 'migrants have gone home' & this affects levels (rather than rates) and as the fall in population is (supposedly) focused on migrants there are major compositional changes due to the different population estimates.

However, our LFS is based on 5 waves & the 1st wave was essentially cancelled during the UK's 1st lockdown (Apr-Jun 2020) which because the attrition rates are biased is, I believe, a more likely reason for the odd compositional results thant the wrong population. Luckily, as the 1st waves resumed the effect should wear out after a year.

Happy to engage in discussion with you if you would find it useful. Bill Wells