The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 5,200 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

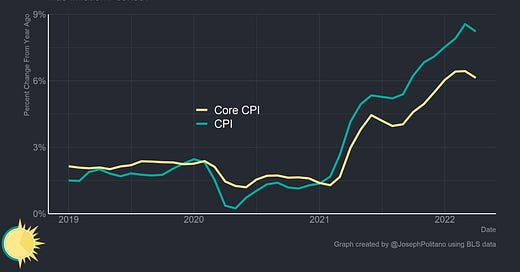

This week’s Consumer Price Index release provided a welcome reprieve: year-on-year inflation slowed from 8.5% in March to 8.3% in April and year-on-year core inflation slowed from 6.5% to 6.2%. The last time year-on-year inflation made any meaningful deceleration was nine months ago—when CPI was clocking in below 5%.

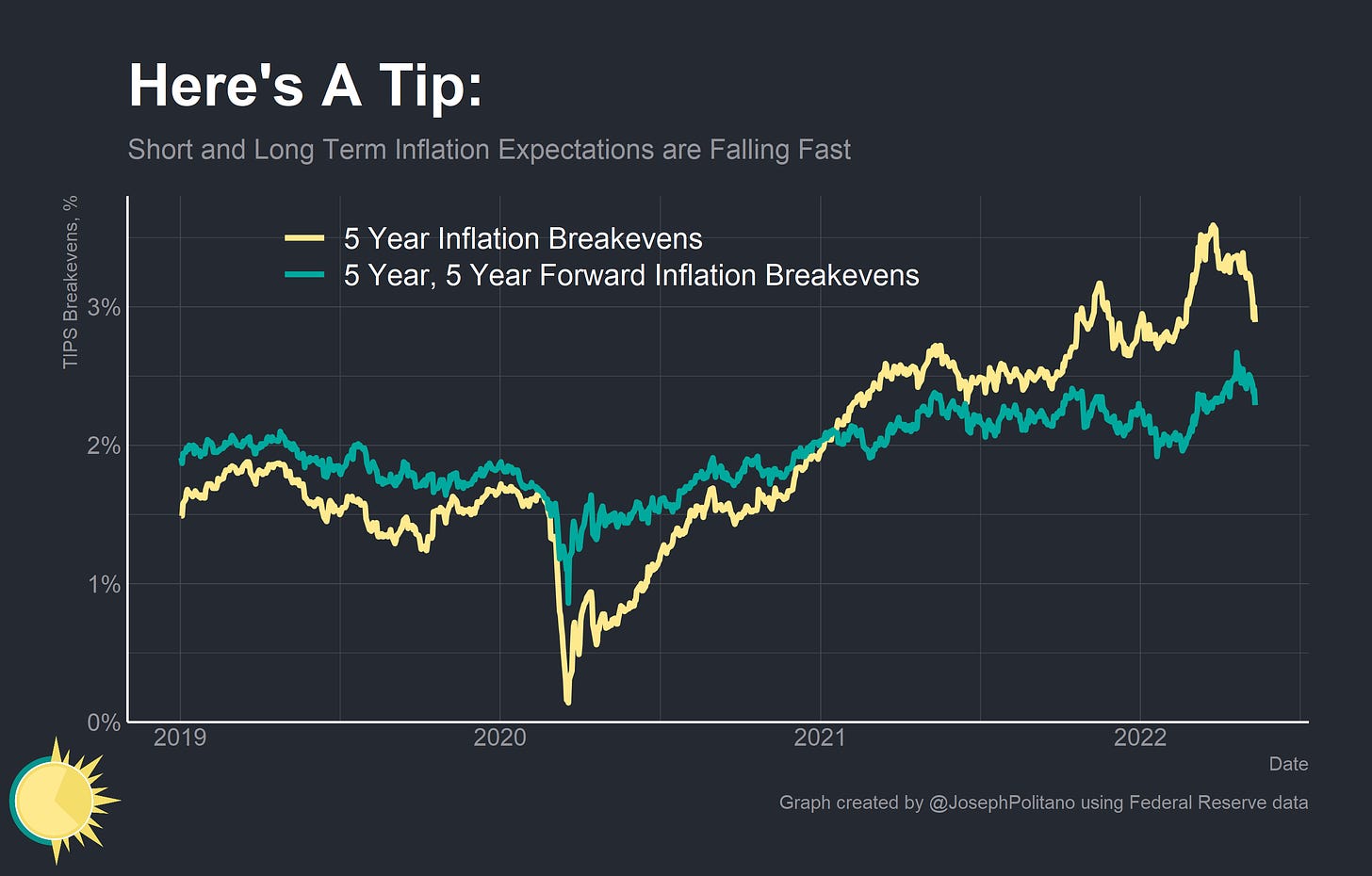

For a variety of reasons, we have likely hit “peak inflation” in the United States. Since annual inflation is just the change in prices over the last year—and since prices were high and growing quickly last spring—base effects will start to slow year-on-year inflation down even if month-on-month inflation growth remains stable. Simple math will therefore likely keep inflation below its recent highs. But there’s more than that: the Federal Reserve is aggressively tightening monetary policy and financial conditions to fight inflation. This is already manifesting as lower short and long term inflation expectations and will likely show up in official price indices soon. Also, the much-anticipated deflation in goods has yet to occur thanks to Chinese COVID lockdowns and the Russian invasion of Ukraine—and that could be a major headwind for inflation going forward.

Still, significant risks remain: the forecasts from the Federal Reserve expect PCEPI inflation—the more comprehensive inflation measure they prefer—to end the year at about 4%. The Blue Chip Forecast expects PCEPI inflation to stay at 6%—barely decreasing from its current levels. A good amount of uncertainty remains in global energy and goods markets thanks to the geopolitical events of the last few months—and inflation could end up higher depending on how the chips fall. Here’s why inflation has likely peaked—and the risk factors that could drive it higher.

Why We Probably Hit “Peak Inflation”

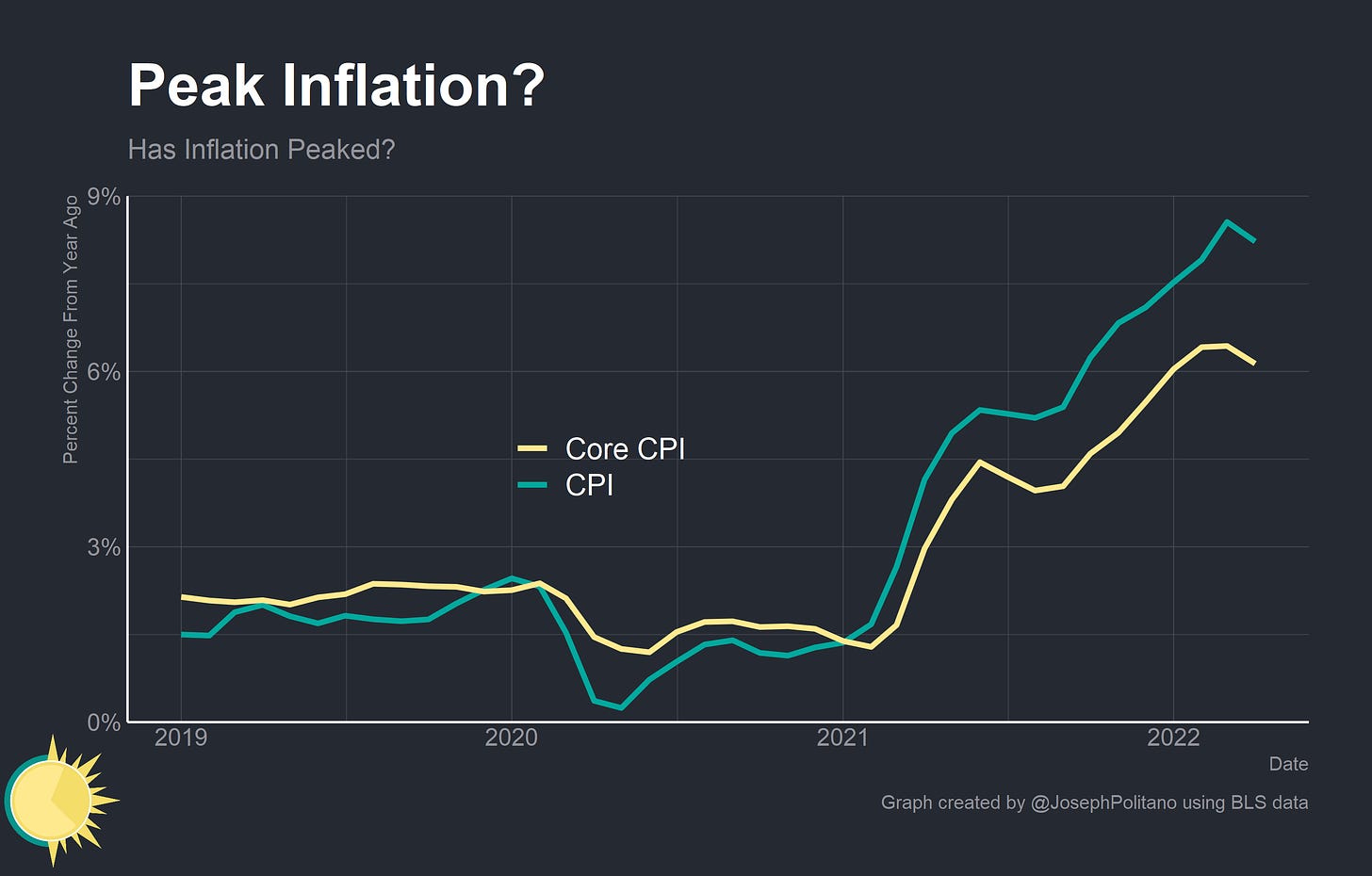

Reason 1: Math

Annual inflation is just the change in prices over the last year. If prices were especially low last year, normal prices today will show up as higher year-on-year inflation. This is a base effect—and it’s part of what drove year-on-year inflation so high in spring 2021. Prices were abnormally low in April 2020 thanks to the pandemic, leading high prices in April 2021 to show up as unusually high inflation. Now, the opposite is happening: the high prices of spring 2021 are causing today’s year-on-year inflation to look abnormally low.

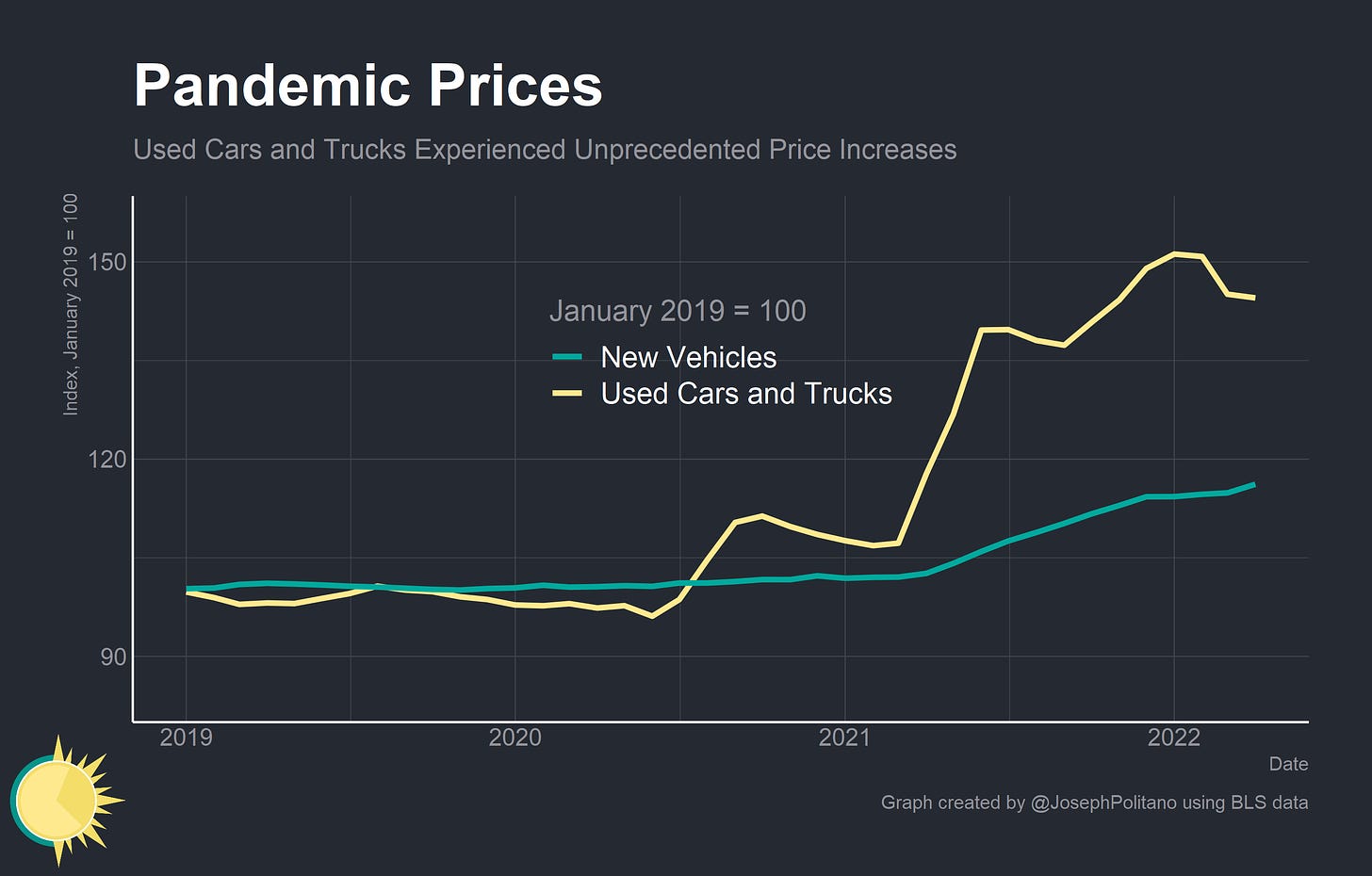

April, May, and June of 2021 had the fastest pace of core CPI growth in nearly 50 years thanks to a spectacular increase in used vehicle and other durable goods prices. That jump in prices was pushing up year-on-year core inflation significantly—until now. With the most recent CPI report, April 2021 became the base month for year-on-year inflation—so despite core inflation actually increasing from March to April, annual price growth decreased because of the base effect. The circumstances that caused the surge in core inflation in spring 2021 were highly unusual, making it extremely unlikely that core inflation will run at a similar pace this spring. The result is that, mathematically, core year-on-year inflation will almost certainly decrease over the next two reports.

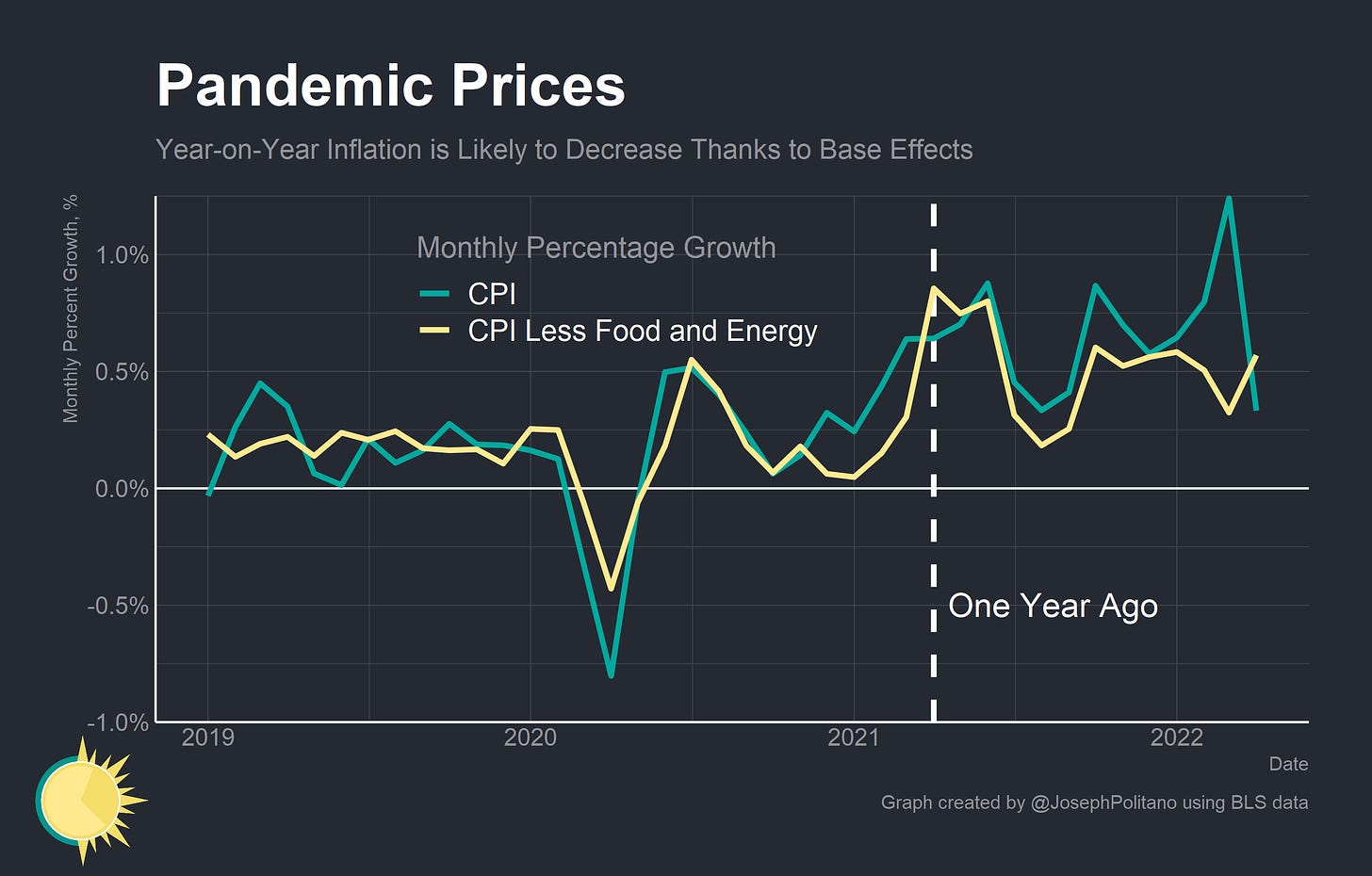

Reason 2: The Fed

The Federal Reserve has also gotten much more aggressive in combatting inflation over the last six months. Regardless of whether you think they are doing too much or too little, the tone shift is self-evident: even the FOMC’s most dovish members are talking about getting more aggressive to fight inflation, and they just approved the first 0.5% interest rate hike in more than 20 years. Financial conditions are tightening in a hurry, and the Fed’s anti-inflation campaign should start showing up in official price data soon.

Indeed, recent moves from the Fed have already done a lot to contain inflation expectations. Inflation breakevens, which measure market-based inflation predictions by calculating the spread between treasury bonds and their inflation-protected equivalents, have sunk back down to February levels after increasing significantly over the last few months. As I’ve written before, these measures are among the most accurate ways to forecast inflation, so their movements are extremely important. 5 year inflation expectations are hovering near 3% and 5 year, 5 year forward inflation expectations (think: inflation expectations for 2027-2032) are below 2.5%. Since these breakevens are based on CPI not PCEPI and embed inflation, liquidity, and other risk premiums, they tend to overstate real inflation expectations slightly; breakevens between 2.3-2.7% would be approximately consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

Reason 3: The Delayed Handoff

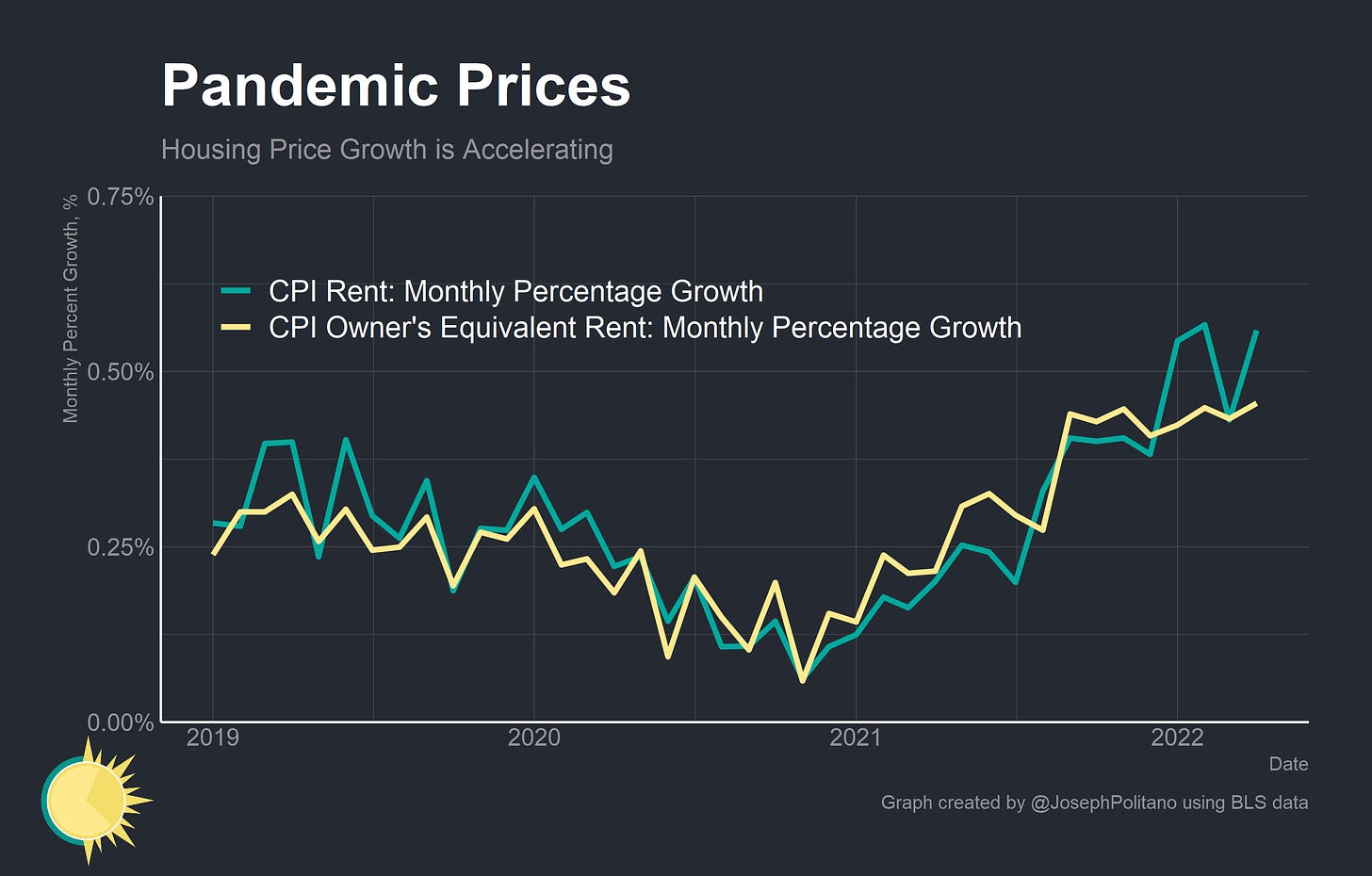

The story of inflation in 2021 was that extremely large price increases in durable goods more than offset slow price growth in the service sector. As the economy reopened, inflation was supposed to “handoff” from goods back to services; durable goods prices would shrink rapidly as services prices grew slightly faster. Since services make up a much larger chunk of the CPI than durable goods, the end result would be generally lower inflation.

That theory hasn’t held up too well so far in 2022. Durable goods prices have only declined modestly, and prices for a wide variety of nondurable goods (especially food and energy) have continued to grow at a fairly rapid rate. Motor vehicle prices contributed about 2% to inflation over the last year, but used vehicle prices have remained stubbornly high in 2022 and new vehicle prices have actually increased somewhat.

(Side note—this month had a relatively unusual jump in new vehicle prices. This might be due to the change in the BLS’s methodology for the new vehicle index, which I flagged last month. Essentially, the old methodology weighed different models by their sales over the last four years while the new methodology only uses the last two months. During the pandemic and the resulting car shortage, rapid shifts in the availability of vehicles caused the new index to be much more volatile and show much larger price increases. It’s not yet possible to completely determine how much the weighting difference affected the April inflation numbers, but it’s something to look out for going forward.)

Regardless, there are good reasons to be (cautiously) optimistic that motor vehicle prices will still come down in the near future. Domestic motor vehicle production has picked as the semiconductor shortage alleviates, and tightening credit conditions and rising interest rates will likely cool auto prices directly. Prices of other durable goods are already cooling, if modestly; appliance costs declined in April and aggregate durable goods prices were essentially flat.

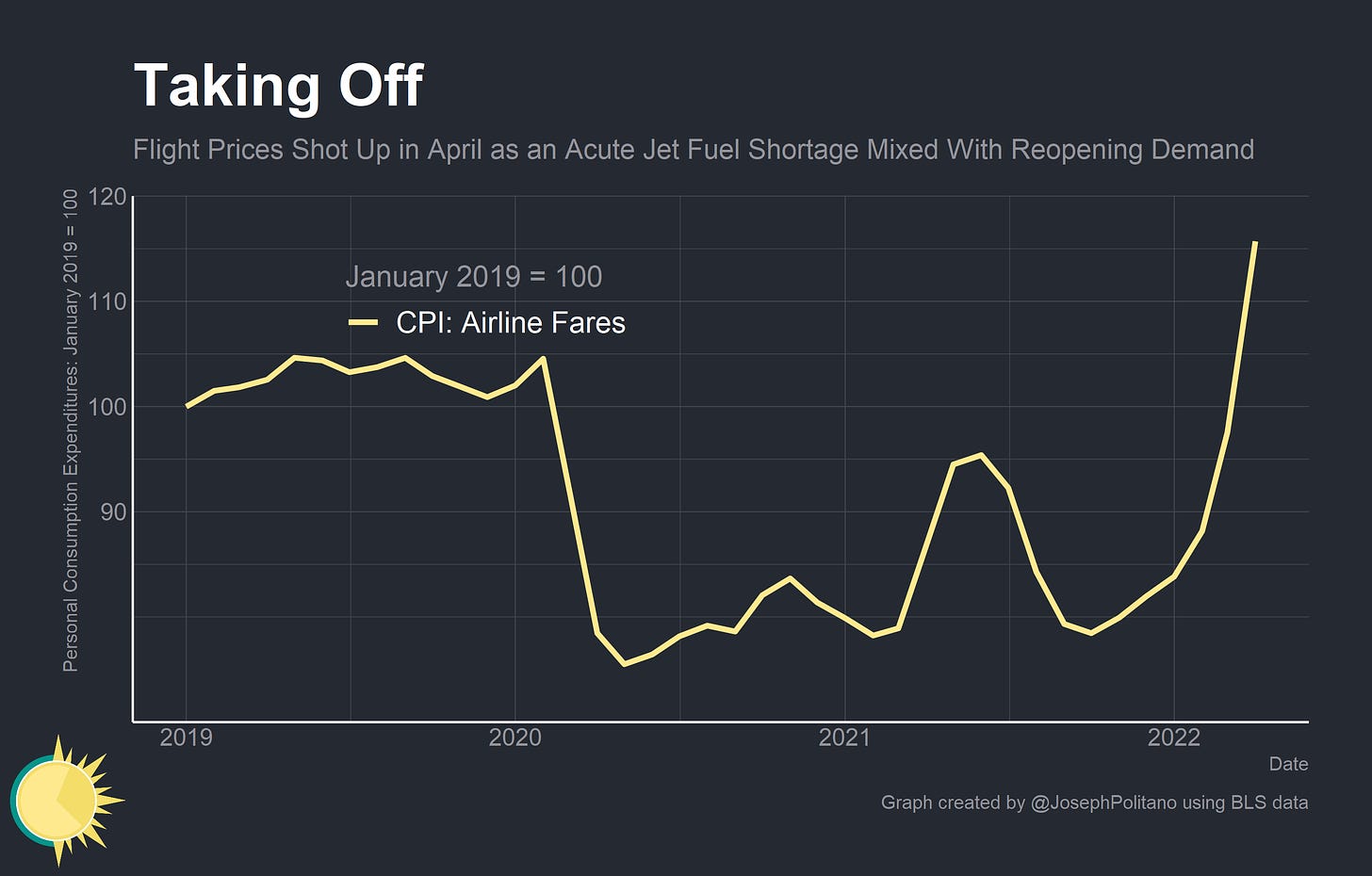

Prices of nondurable goods—particularly energy goods—have also interrupted the inflation handoff over the last couple months. Airline fares were the big story last month; they jumped 18% and exceeded pre-pandemic levels. An acute shortage of jet fuel and rising crude oil prices are weighing on global energy and logistics markets, and the pain is likely to continue for the near future. Gasoline costs dipped 6% in April, but that was mostly due to seasonal adjustment—unadjusted, prices only declined 1% and likely have room to increase given current crude oil prices. Utility (piped) gas prices are also rising as more American natural gas is shipped to Europe or substituted in place of other energy sources.

Services prices, meanwhile, are growing at stable but relatively high rates. The housing half of services prices are growing at nearly 0.5% per month, more than making up for their slow growth in 2020 and early 2021. Strong employment and wage growth, alongside low rates of housing completions and the ongoing housing shortage, are likely to keep rental cost growth high for the near future.

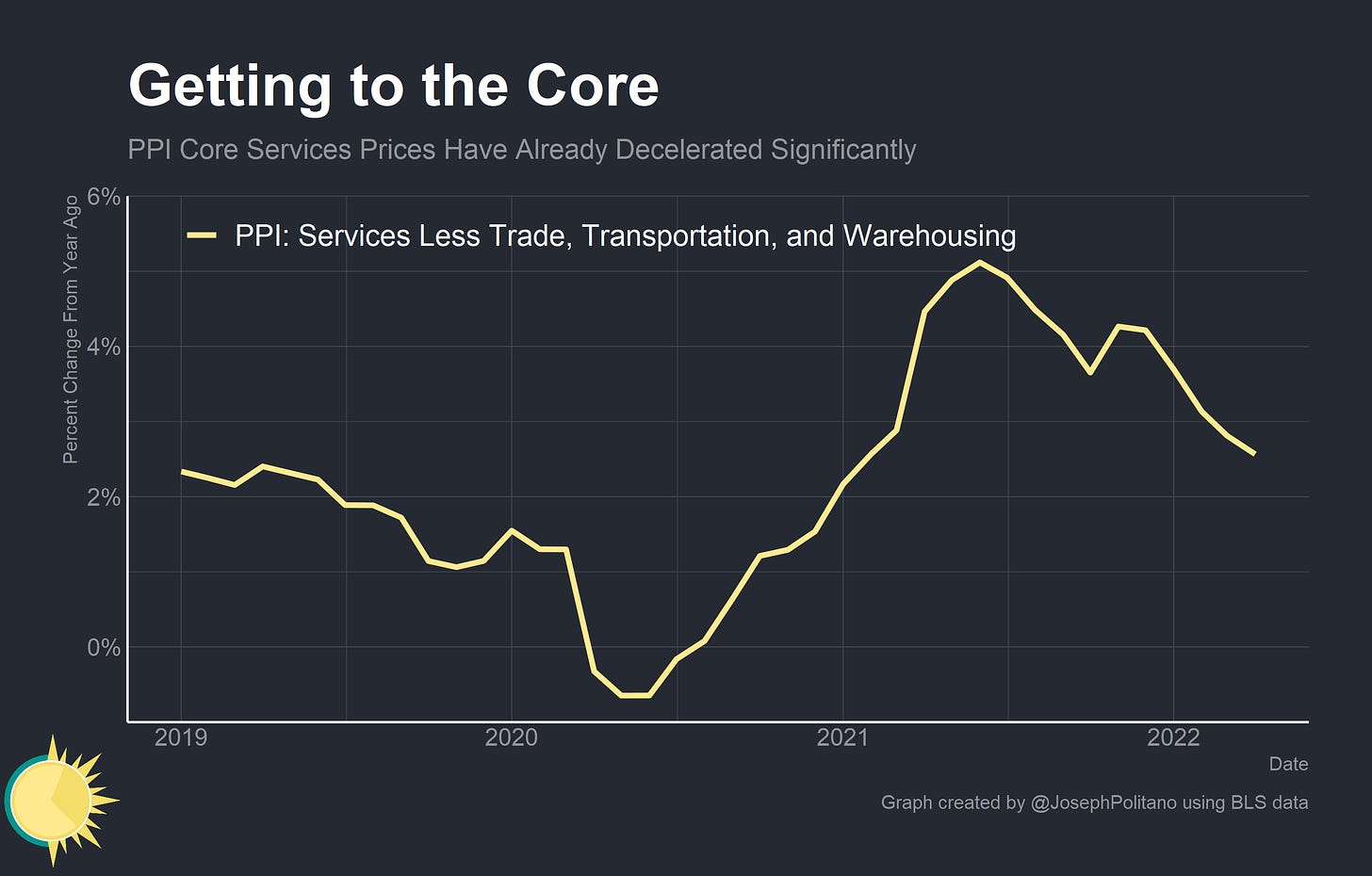

Thankfully, the other half of services prices—labor intensive consumer services—look to be peaking. While growth in services excluding housing was relatively strong in the CPI, it is important to ignore the energy-and-gas dependent services industries like trade and transportation. “Core” services inflation in the producer price index has already peaked, and prices have been relatively stable over the last three months. The PPI is not equivalent to the CPI, but it is clear that CPI services growth is now more about housing and oil than general consumer services.

Why we Might Not Have Hit Peak Inflation

With all that being said, there are two big reasons why we may not have hit peak inflation: China and Russia. To be more specific, China’s COVID lockdowns and ensuing supply-chain snafus have the potential to adversely impact global goods prices. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing sanctions continue to upset global energy markets, and global oil production shortfalls are a source of major uncertainty in global markets.

In China’s case, the strict COVID lockdowns imposed throughout much of the country are restricting production in the country’s export-focused manufacturing sector. Purchasing Managers’ Indices show Chinese industrial output firmly in contraction territory, with readings worse than any time outside the global financial crisis and the early pandemic. That’s extremely bad given how dependent global manufacturing supply chains are on China, but thankfully the full effect of the downturn isn’t being felt in the US yet. Demand for manufactured goods and electronics is decreasing as the economy continued to reopen, and global shipping firm Flexport actually believes that the lapse in production may have actually given time for Chinese ports to alleviate some of their existing backlog. Indeed, the lockdowns are likely currently reducing US inflation by shrinking global energy and gasoline demand, though the situation is rapidly evolving and remains an important possible source of future price changes.

In Russia’s case, the effects are more obviously concentrated in global commodity prices. Oil and natural gas prices were already high thanks to weak production growth domestically and an inability for OPEC+ members to hit production targets. That’s gotten worse as Russian oil output missed production targets by 1.29 million barrels per day in April, though that’s overstating the problem as domestic Russian consumption also took a significant hit. Nevertheless, the current problem isn’t so much about crude oil as it is about diesel and jet fuel, both of which are currently experiencing extremely acute shortages. That’s likely to feed into airfares, transportation costs, and general goods prices in the near future.

Conclusions

Even if inflation has already peaked, it is more than likely to remain high by historical standards. CPI inflation is already a hair above 3% for 2022, and we are only a third of the way through the year. Granted, a large chunk of that is gas prices alone, but even core CPI is still well above its normal pace. Getting CPI to remain in the 4-5% range for the year would likely require rapid deflation in the pandemic-affected supply-chain-sensitive sectors like motor vehicles and other durable goods. It would also require relative stability (or price decreases) in the food and energy sectors, both of which are extremely volatile right now.

Forecasting short-term inflation has been incredibly difficult throughout the pandemic, and the last few months alone have seen some unprecedented shifts in the macroeconomic environment. If the error bands on your inflation forecasts are not large, you aren’t thinking enough about possible edge cases. For the reasons laid out here I believe the worst is behind us, but I acknowledge that outcome variance remains extremely high. Headline inflation could easily plummet if Chinese fuel demand continued shrinking while global production increased, or inflation could jump up again if goods supply chains backed up further due to lockdowns abroad. Just today India announced it will be banning wheat exports in an attempt to control domestic prices—an event that will marginally bump up food prices in the US and would have been difficult to predict six months ago. Those kind of adverse supply shocks still pose significant risks to the US economy, and remain critical to watch out for going forward.

Wonder why Fed & Officials have been so unclear about the macroeconomic definition of “transitory” -prices adapt to increased supply and demand factors- leaving the public & media to understand such an important term in its ordinary sense, ie as time passes. Most of the risks we face now are pretty similar to 2021. Thanks for Apricitas!!!

Can you add a PDF print button, please? I usually print off good articles to read later. Thank you.