Russia's New Friends

Cut off From Trade With the US, EU, Japan and Others, Russia is Turning to New Friends: China and Turkey

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 23,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

This is the first in a two-part series focusing on the economic aftermath of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine for the war's 1-year anniversary. This post will focus on Russia's trade relationships and efforts to circumvent sanctions, and next week's post will focus on the disparate global impact of the war economy.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in late February of last year, an international alliance of high-income democracies sought to craft a swift economic and military response. The bulk of the military response came in the form of arms, equipment, and training for Ukrainian troops to help them better resist the Russian invasion—European and American leaders were largely unwilling to directly involve their armed forces in open combat with Russia for fear of escalating the conflict. The economic sanctions were likewise crafted with a major restriction—they had to hit Russia’s economy hard in order to deter further aggression and minimize the industrial capacity that could be leveled against Ukraine, but they had to preserve the Russian oil and gas exports that were essential for basic global (and especially European) energy consumption.

The plan was to leverage the high-income democracies’ economic strengths—high-tech manufactured goods and international finance—to cut Russia off from critical imports and sources of credit/liquidity. Meanwhile, Russian energy exports would be excluded from much of the sanctions in order to prevent an international crisis. Russia did eventually retaliate by cutting off much of Europe from natural gas supplies, but European nations have been able to largely decouple from reliance on Russia through unprecedented imports of Liquefied Natural Gas and fortuitously warm weather. Sanctions successfully kept Russian oil flowing to nations like India and China at significant discounts to global market prices, depriving Russia’s government of critical revenue, although the loss of Russian refinery capacity kept gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel prices comparatively elevated.

Largely, the Allies’ strategy worked: Russian businesses and markets were roiled by the original round of financial sanctions, and Russian industrial output has suffered after being cut off from critical imports. The Russian economy has entered a significant recession this year, with GDP dropping 3.7% over the year ending in Q3—a collapse in output nearly on par with what the US experienced during the Great Recession, and that’s despite today’s Russia enjoying significant tailwinds from rising energy prices. The decision to weaken Russia’s industrial base proved especially important as the war in Ukraine bogged down into an extended conflict—with less capacity to resupply vehicles, materials, and ammunition, the Russian army has lost ground to Ukrainian defenders and has been forced to devote hundreds of thousands more people to combat operations just to consolidate early war gains.

However, the squeeze on Russia’s industrial base via restrictions on key Russian imports is easing. Cut off from trade with high-income democracies, Russia has been making new friends and new trading partners—and now total Russian imports are steadily recovering. The bulk of that comes from Russia’s rapidly-growing trade relationship with China, but Turkish exports to Russia are also contributing—and there are signs of possible reexports through Russia-friendly ex-Soviet states. The easing of trade restrictions will shift the war’s balance of power in Russia’s favor—putting a just peace agreement even further out of reach.

The Rising Russia-China Trade Relationship

China was always the obvious first choice for Russia to turn to when the Allies began implementing sanctions. The two share a large border, reciprocal needs for each other's exports, and similar proclivities for authoritarianism and military aggression. Russia could supply China with lots of much-needed oil and natural gas—given time to build out the necessary infrastructure—and China could supply Russia with the kind of cars, phones, computers, and machinery it previously imported from the Allies. At the immediate onset of the invasion, Chinese exporters were hesitant to sell to Russia and overall exports fell dramatically—but over time Chinese exports to Russia came roaring back to record highs. As did imports, as China increasingly turned to discounted Russian oil and natural gas for its energy needs.

That renewed surge in exports has been especially large in the kind of complex durable goods that were hit hardest by the initial sanctions. Chinese exports of machinery, electronics, and vehicles to Russia have all risen significantly throughout 2022. Vehicle and vehicle-related exports in particular have been up like a rocket over the last few years, with exports to Russia already doubling the pre-invasion peak. But in general, a lot of Chinese exports to Russia represent what Matt Klein calls “dual purpose goods”—exports that, civilian or not, could be repurposed by Russia for their combat utility or used to alleviate constraints on military supply chains. However, even if these Chinese exports are not directly benefitting the Russian operations in Ukraine, they bolster the Russian economy and make it more resilient to the kind of sanctions the Allies have put in place so far.

Of course, semiconductors and related computer parts are among the most central sectors to the ongoing trade war, with sanctions levied against both Russia and China in efforts to curtail their domestic chip capabilities. That's what makes the recent surge in Chinese semiconductor exports to Russia so important—China is replacing lost Russian imports from Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and other democratic chip powerhouses while sturdying up their domestic industry in the midst of a broad chip slowdown.

Russia’s Black Sea Buddy

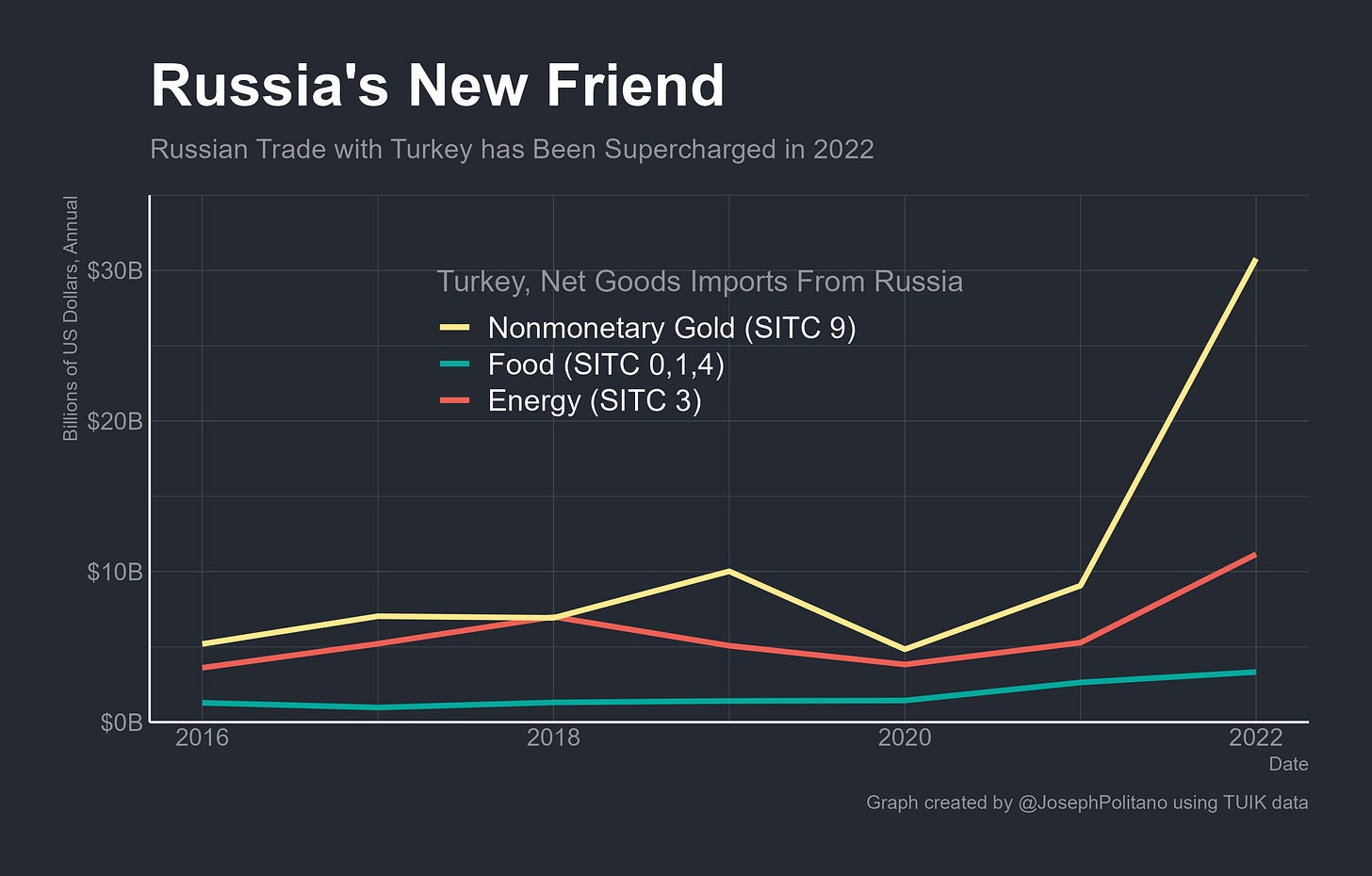

Although China is by far the largest source of new Russian imports, it is not the only one—nor is it the fastest growing. That distinction belongs to Turkey, which has seen its trade with Russia grow significantly since the start of the invasion last year. Turkish exports to Russia are up a staggering 120% in the last year, and imports from Russia remain elevated amidst higher global food and energy prices.

Turkey's trade with Russia tells a similar story to China's: the nation is less on board with international sanctions, more dependent on Russian energy, and now exporting significant amounts of manufactured goods back to Russia. What makes Turkey unique is the massive amount of nonmonetary gold that the country imports from Russia—Turkish inflation is at a staggering 58% right now according to official figures, leaving many people scrambling for ways to protect their savings. Many of them are turning to gold, and much of that gold is coming from Russia. Turkey is rumored to be restricting gold imports in the wake of the devastating earthquake that hit the region earlier this month, but it’s hard to predict how that will shake out.

Meanwhile, Turkey, like China, is helping to fill some of the vacuum left behind as companies left Russia in the wake of sanctions. Turkish net exports of machinery, vehicles, transportation equipment, and other manufactured articles to Russia surged to a record high in 2022, rising more than 50% compared to 2021.

Conclusions

The war in Ukraine will turn one year old soon—and right now there is little end in sight. Russia’s economic woes don’t look to be ending either—drops in energy prices and the ongoing cost of the war are weighing heavily on the nation. Weakening pressure on Russia's domestic industries is likely to prolong the war and require more support for Ukraine to counterbalance—which is part of the reason American and European governments are committing more advanced military hardware to the Ukrainian forces and adopting new strategies.

Recently, sanctions have focused more on hitting Russian energy export revenue rather than intensifying restrictions on imports. Price caps and certain bans on oil and petroleum products will certainly hurt the Russians, but the bigger impact arguably comes falling energy prices overall. To the extent Allied policymakers feel more energy-secure and see less risks of an energy crisis, they are more willing to hit Russia's energy exports.

But if policymakers are serious about achieving a just peace that preserves Ukrainian democratic sovereignty while ending the death and destruction caused by the war, they will likely have to leverage further sanctions in order to cut Russia off from it's new friends. Turkey im particular—a NATO member with close ties to the US and European Union—will likely become a diplomatic battleground if their relationship with Russia continues to grow. China—already a frequent target of sanctions—will likely come under further pressure to the extent it's seen as supplying Russia's war machine directly. More than anything, it will solidify the role of global trade as another battlefield in the ongoing conflict.

“But if policymakers are serious about achieving a just piece that preserves Ukrainian democratic sovereignty….” Hi Joseph, I think you meant “a just peace”?

Can we not also forget how South Africa are pivoting towards China and Russia with their joint military exercises.

They should be called out for this. Africa as a massive blind spot for the west.