Russia's Recession

The Country is Suffering Severe Economic Pain—Though it Has Proved More Resilient than Expected

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 18,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year was met with a swift response from allied nations—the Central Bank’s assets were frozen, harsh restrictions were placed on Russian financial companies, and a wave of broad sanctions hit Russian imports and exports. Inflation shot up immediately as critical consumer goods became scarce and the country struggled to carry out basic international financial transactions. The nearly unprecedented strength of sanctions deployed against such a large country caused organizations like the IMF to expect massive drops in Russian GDP. Meanwhile, combat operations in Ukraine first began to stall and then started reversing Russian progress, putting Vladimir Putin in an even worse position. Left with few economic options, Russia began cutting off large swathes of Europe from critical natural gas supplies—permanently scarring one of its most valuable trade relationships and cashing in its biggest economic chip.

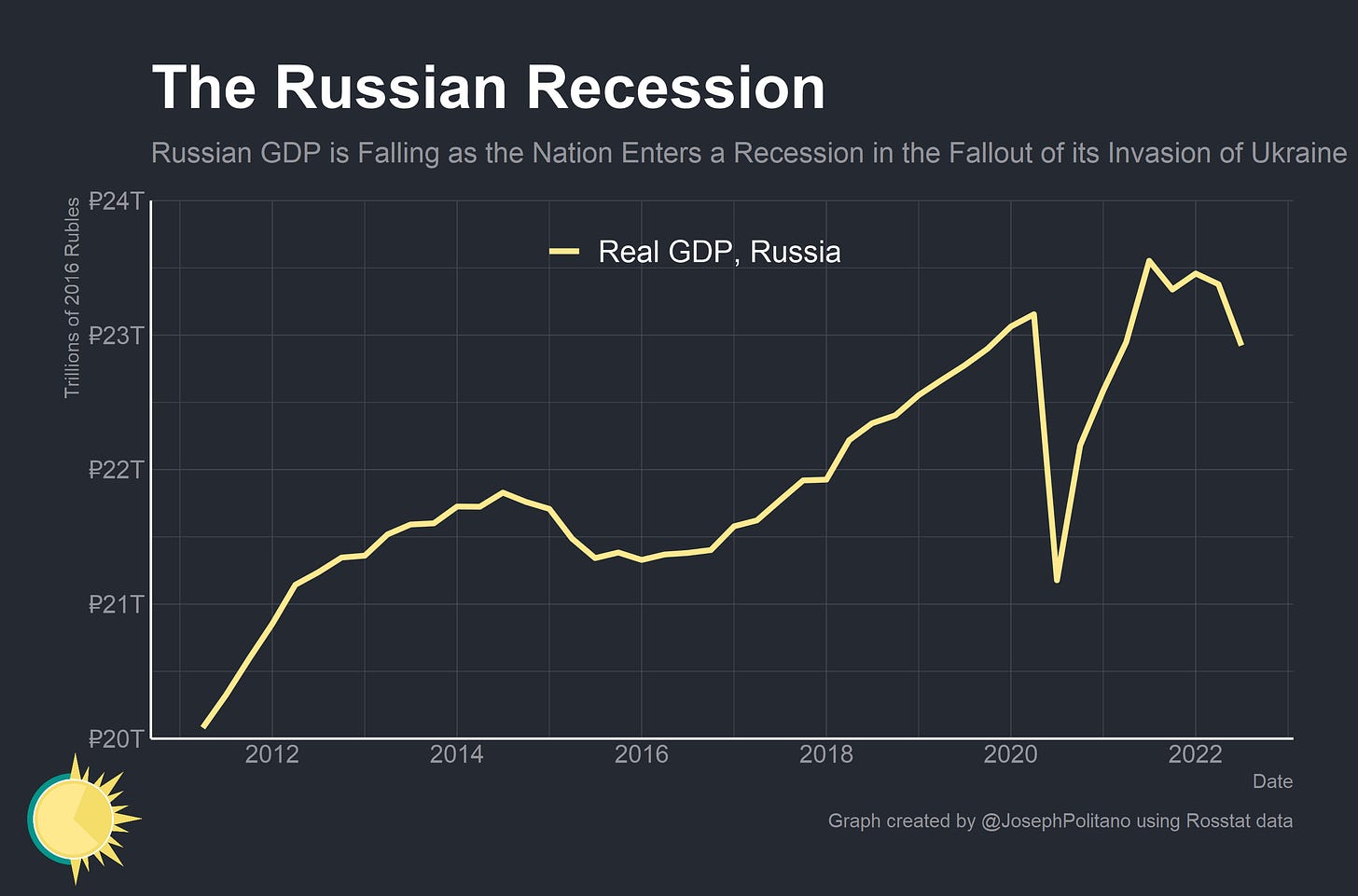

Given all that, the Russian economy has certainly performed much better than expected. After initially forecasting an 8.5% drop in GDP this year, the IMF now expects the Russian economy to contract by only 3.4%. The Russian central bank has lowered interest rates amidst a relatively brighter inflation outlook and Russian imports of manufactured goods have bounced back thanks to increasing trade with China and Turkey.

Still, forecasts were so dire that even better-than-expected results leave Russia facing a massive recession and significant economic problems. Capital flight is rampant, annual inflation sits above 12.5%, consumer confidence is atrocious, credit conditions are tight, complex manufacturing industries are struggling, the country’s oil and gas revenues may be shrinking, and hundreds of thousands more young people are now going to be conscripted into the armed forces. Sanctions have still worked to inflict heavy pain on the Russian economy—though it remains to be seen how much Russia can continue to adapt moving forward.

Cut Off

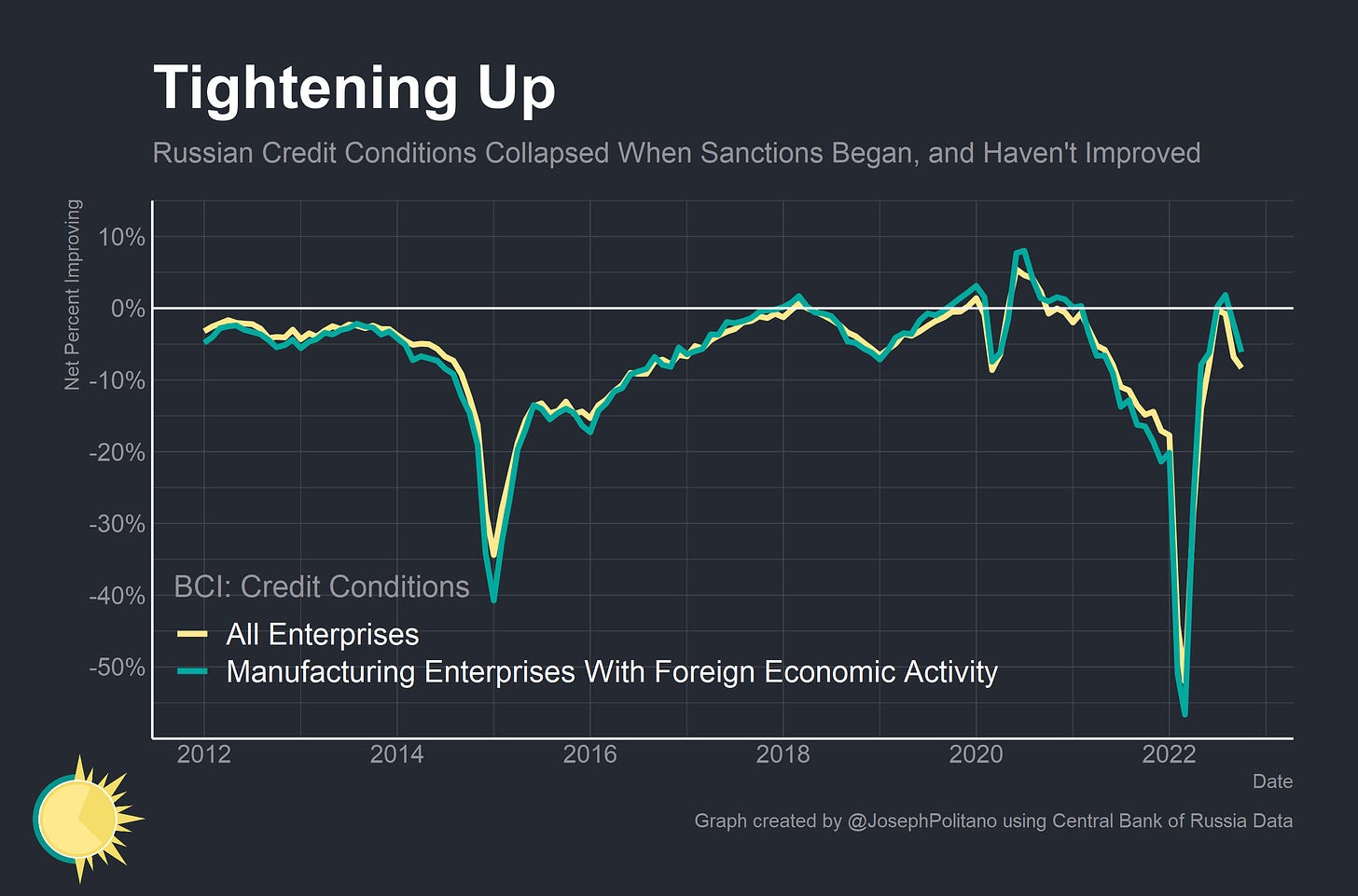

The initial wave of sanctions had to work around the fact that Western European economies are highly dependent on Russian natural gas for essential, inelastic energy supplies. The goal then became to neutralize the value of the dollars and euros spent on Russian gas by targeting Russian financial institutions and leveraging the global financial centers located in London and New York. That part of the plan worked as intended—Russian companies reported a massive deterioration in credit conditions as sanctions came into effect earlier this year, and conditions have barely improved since then despite the efforts of the Central Bank of Russia.

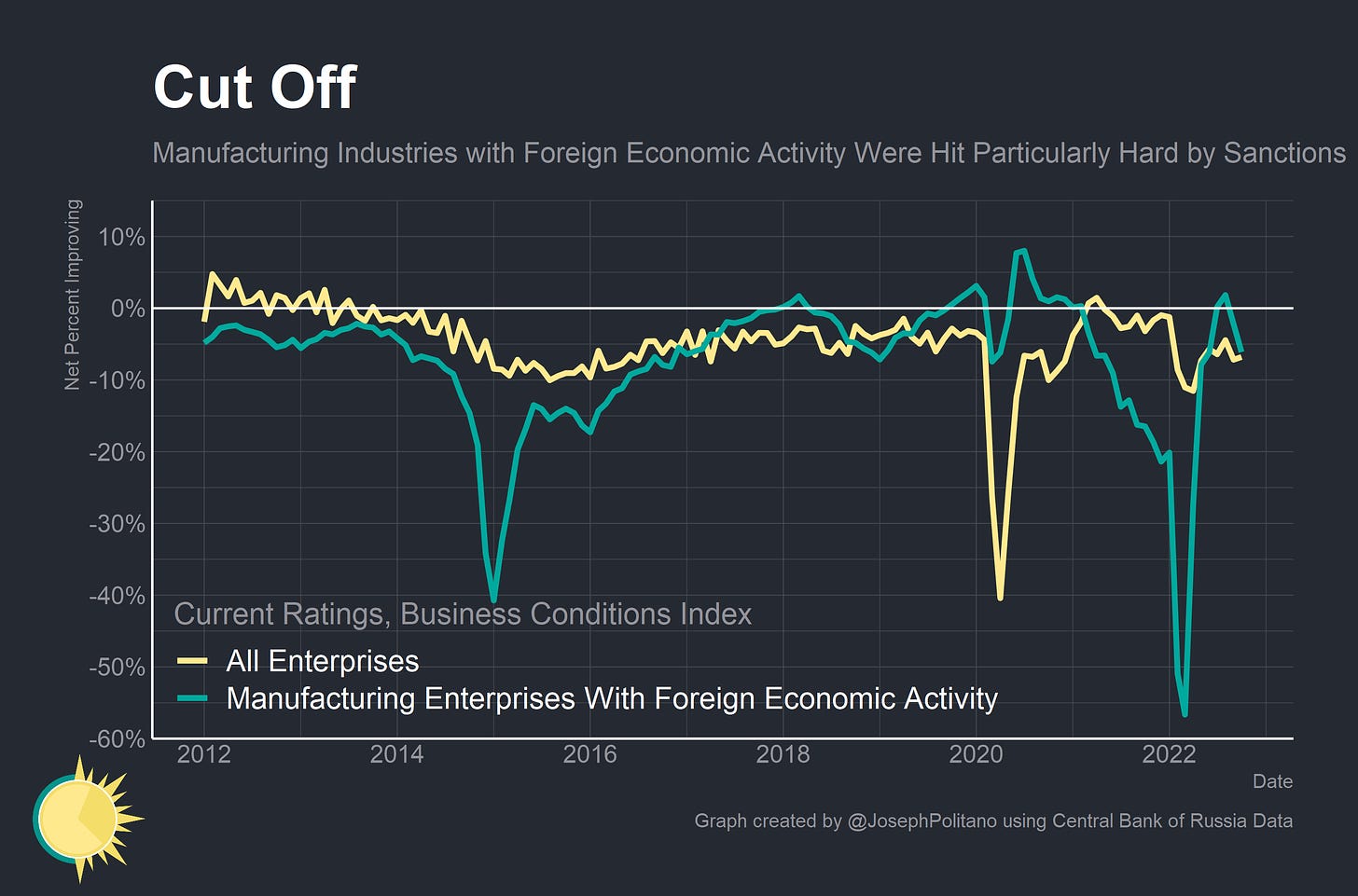

The second prong of this effort entailed cutting Russian consumers and businesses from critical manufactured goods. While Russia had significant leverage through energy supplies, the country was dependent on imports for many consumer goods and would need semiconductors, vehicles, and other complex manufacturing items in order to wage war effectively. Sanctions could therefore have an outsized influence on Russian industry, consumption, and combat capabilities through targeted trade restrictions. That’s exactly what we saw within the Russian business sector, as manufacturing industries with significant foreign economic activity took much larger hits from the initial sanctions and have struggled to recover since.

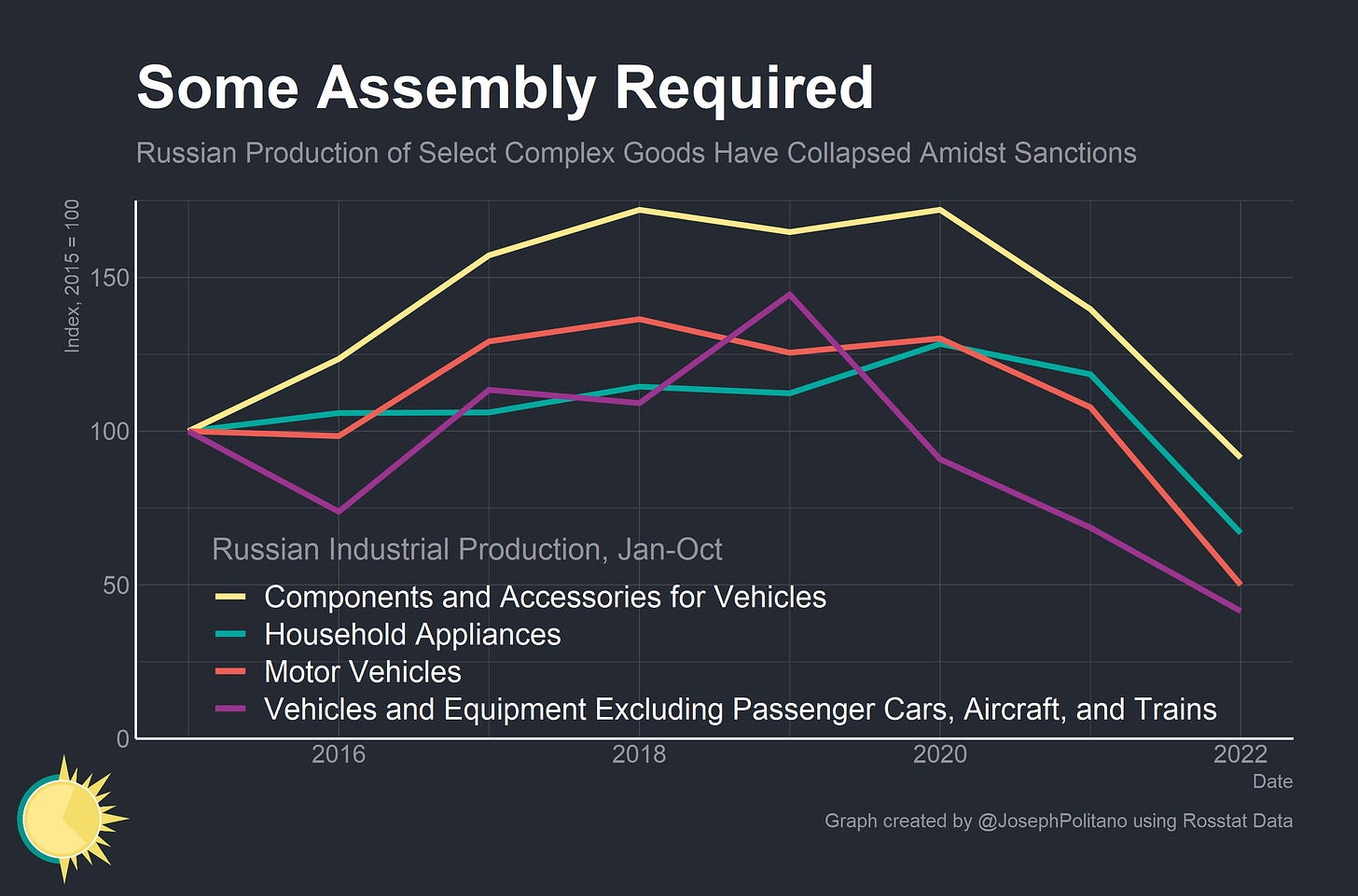

Indeed, production for key complex goods in Russia has completely tanked—with motor vehicle production down more than 50% and household appliance output shrinking by more than 40%. The manufacturing output of other key goods like computers and electronic equipment is also down 14% from 2019 levels. Impairing output in complex industries was key to hurting Russia’s war machine and buying time for Ukrainian forces to mount a strong defense—and it seems to have worked as intended.

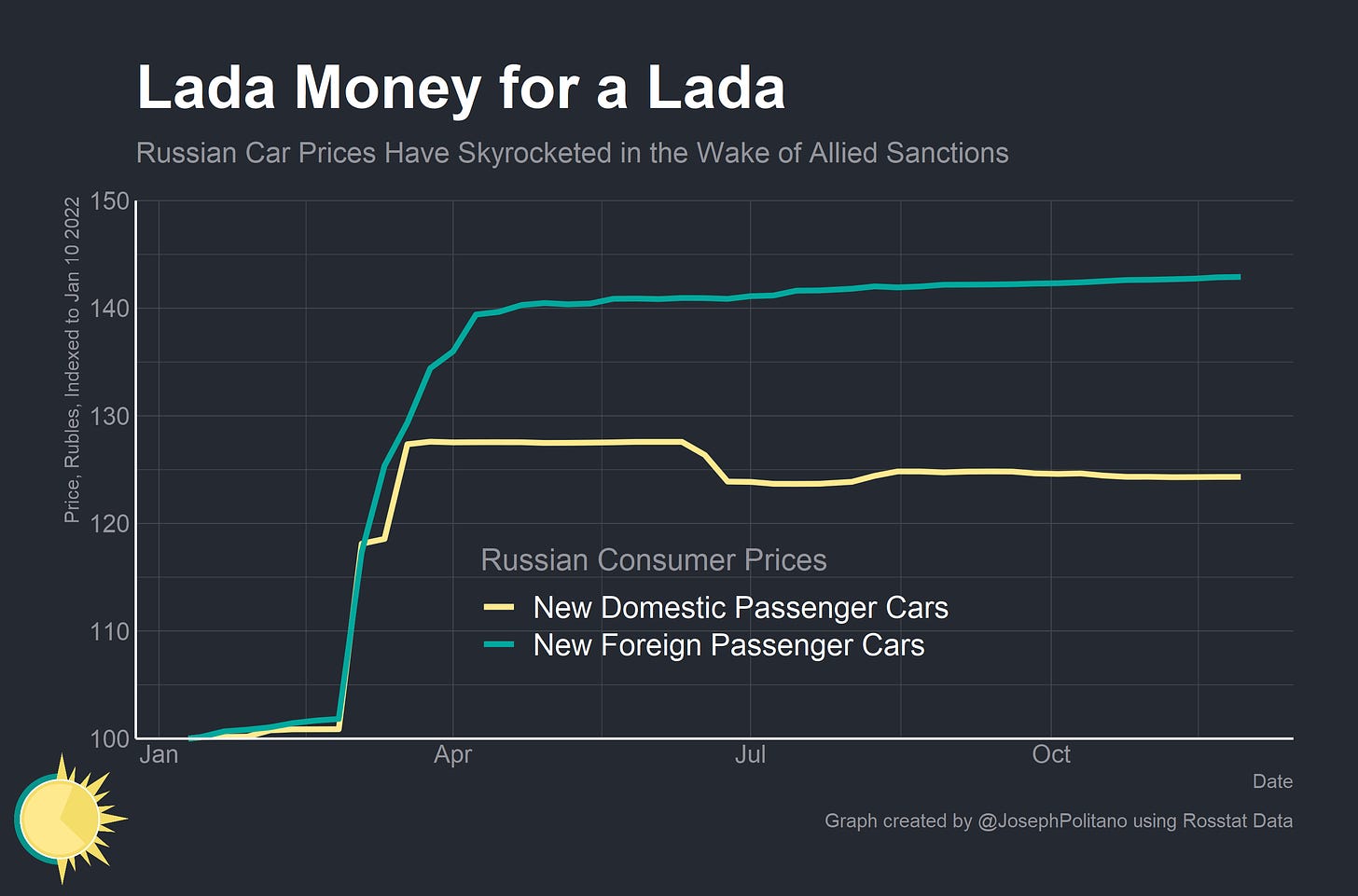

However, it has had the added effect of cutting Russian businesses and consumers off from key production goods too. Prices for new domestic and foreign passenger cars in Russia have increased by 25% and 43% respectively since sanctions were imposed at the beginning of this year, and Russian vehicle manufacturing is still struggling to even get production back to 2021 levels amidst input shortages. In fact, prices for all sorts of essential manufactured goods have increased dramatically since the start of this year—bath soap is up 44%, toothpaste is up 40%, diapers are up 22%, menstrual products are up 44%, smartphones are up 6%, and a variety of over-the-counter drugs have seen massive price hikes too.

Russian output declines are not just limited to complex manufacturing industries either—over the last year, real oil and natural gas output has also shrunk alongside manufacturing. Compared to last October, steel and iron production is down 12.3%, fertilizer production is down 9.4%, metal ore mining is down 7%, and coal mining is down 3.3%.

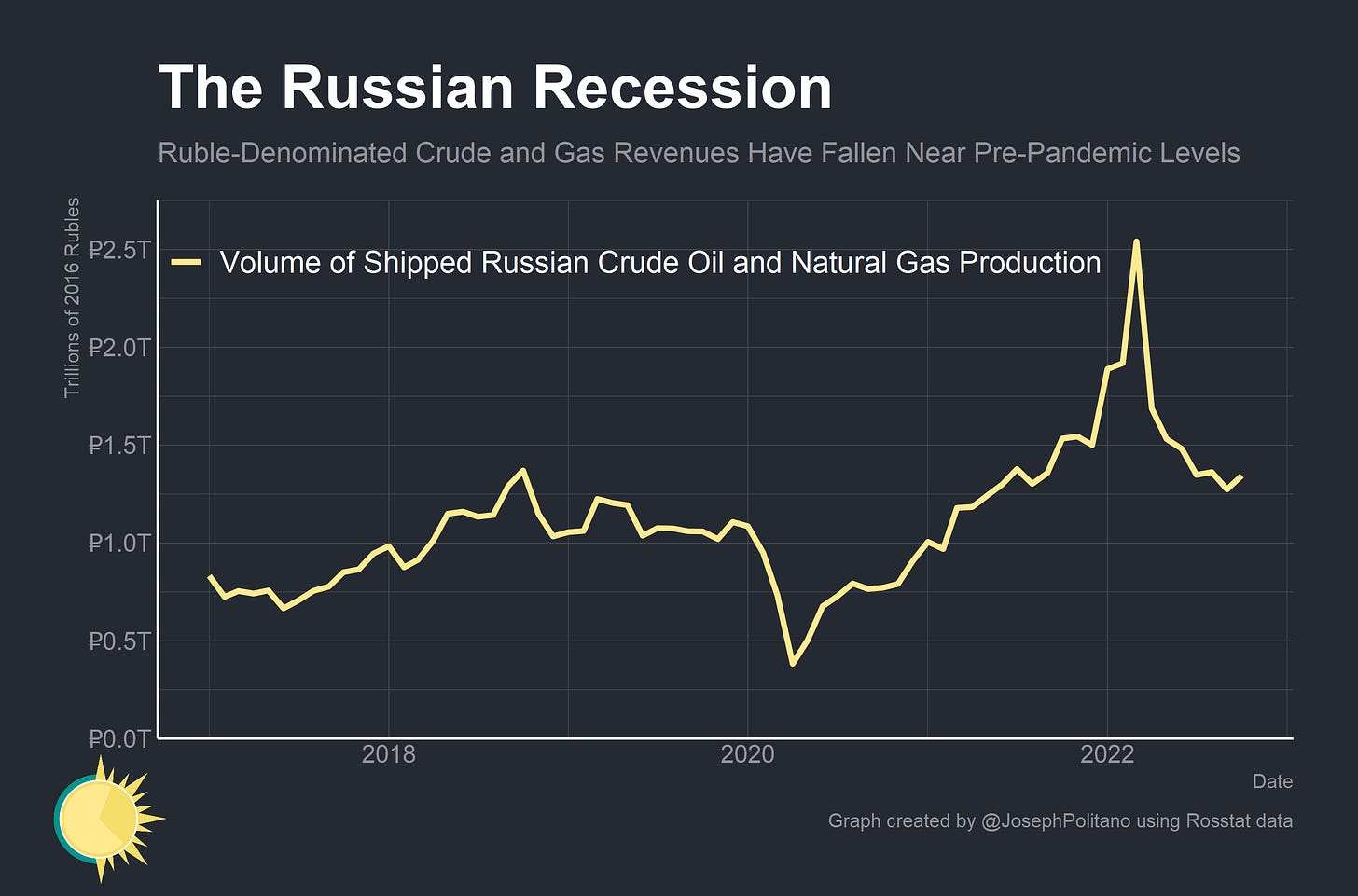

That’s one reason why, despite elevated natural gas and oil prices throughout the year, Russian energy revenues have likely declined significantly from their peak. Russia has been forced to sell its crude oil at a discount to buyers in India, China, and elsewhere as sanctions bite—and it also dramatically cut the volume of natural gas sent to Europe. A new $60 a barrel price cap on Russian oil imported to Europe could hamper Russian energy revenues further, but broad declines in global oil prices likely matter more than the specifics of the cap—and for the war effort, Russian trade in manufactured goods likely matters more than direct energy revenues.

Conclusions

War, in the modern era, usually does not carry a positive return on investment. Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine—in which it seized Crimea largely bloodlessly—was (arguably) one of the 21st century’s only exceptions, as the country was able to grab a large swathe of territory and access to critical warm-water seaports in exchange for tough but comparatively weatherable sanctions. This invasion of Ukraine looks to fit the rule—thanks to dogged defense by Ukrainian forces and a strong economic response from a coalition of nations, Vladimir Putin is paying a massive economic price for his invasion of Ukraine.

Still, it is inarguably Ukraine that is bearing the brunt of the economic damage wrought by the war. The Ukrainian State Statistics Service—which is still publishing key information even as the conflict rages on—estimated that the country’s GDP shrank nearly 40% since last year once you account for population and territory loss. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that 7.8 million Ukrainians—about 18% of the pre-war population—have been forced out of the country since the start of the Russian invasion. Tens of thousands have likely already died in the fighting, and millions across the world are still suffering in the economic and geopolitical fallout of the invasion. It’s an important reminder of the tragic human cost of war, and why economic punishments need to be used today as an effective deterrent for tomorrow’s would-be aggressors.

It’s certainly interesting to see how sanctions play out. There is the immediate shock of the sanctions but it feels as though it’s more the long term impact that eventually turns the screw.

I wondered when first implemented whether the West had the same power these days when there are other markets that Russia can tap into. China and India being the big ones.

It does appear from your article that the sanctions are biting and Russia are isolated to some extent at least.

The citizenry of Russia seem to be facing economic pain (e.g. higher car prices, lower production of household appliances, declining real wages due to inflation). In the future, is it possible to design sanctions that hurt the government/military of an aggressive nation without tightening the belt on ordinary citizens? Were efforts to do so taken this time around?