Sanctions on Russia Won't End the Dollar's Reserve Currency Status

The Dollar is the Center of the Global Economy, and Will Remain that Way

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

Also! I’m taking questions for an upcoming mailbag/Q&A blog post. If you’ve got a question you’d like to see me answer please submit it through this form!

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine last month, the United States and its allies imposed among the strictest sanctions possible on the Russian economy. Russian financial institutions were cut off from the interbank messaging system SWIFT, dealings with Russian corporations (besides energy exporters) were heavily restricted, and hundreds of billions of dollars in Russian foreign currency reserves and sovereign wealth fund assets were effectively frozen. The effects on the Russian financial system were immediate and drastic—the price of the ruble plunged, many international companies abandoned their Russian operations, and the central bank raised rates from 9% to 20% within hours in an attempt to prevent a complete crisis.

At some level, this was an incredible economic “show of force” from the US. As the issuer of the world’s reserve currency—the currency used for the vast majority of international trade, payments, and savings—the US has unique power over the global financial system. In recent years it has deployed this power extensively against geopolitical rivals, but the only countries previously hit with sanctions of similar size and scope were smaller economies like Iran and Venezuela. Never has a country as large, populous, or economically powerful as Russia been hit with sanctions this extreme.

Yet in the wake of sanctions the primary concern appeared to not be for Russia’s currency but for America’s. Reporters asked Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell if they expected the US Dollar to lose its reserve currency status. Rumors about Saudi Arabia coming to a deal with China to price oil sales in Chinese Renminbi received breathless coverage on Twitter. This is far from just a social media phenomenon—Credit Suisse’s preeminent global money expert Zoltan Pozsar predicted a new global monetary system headed by China and “backed by a basket of commodities.”

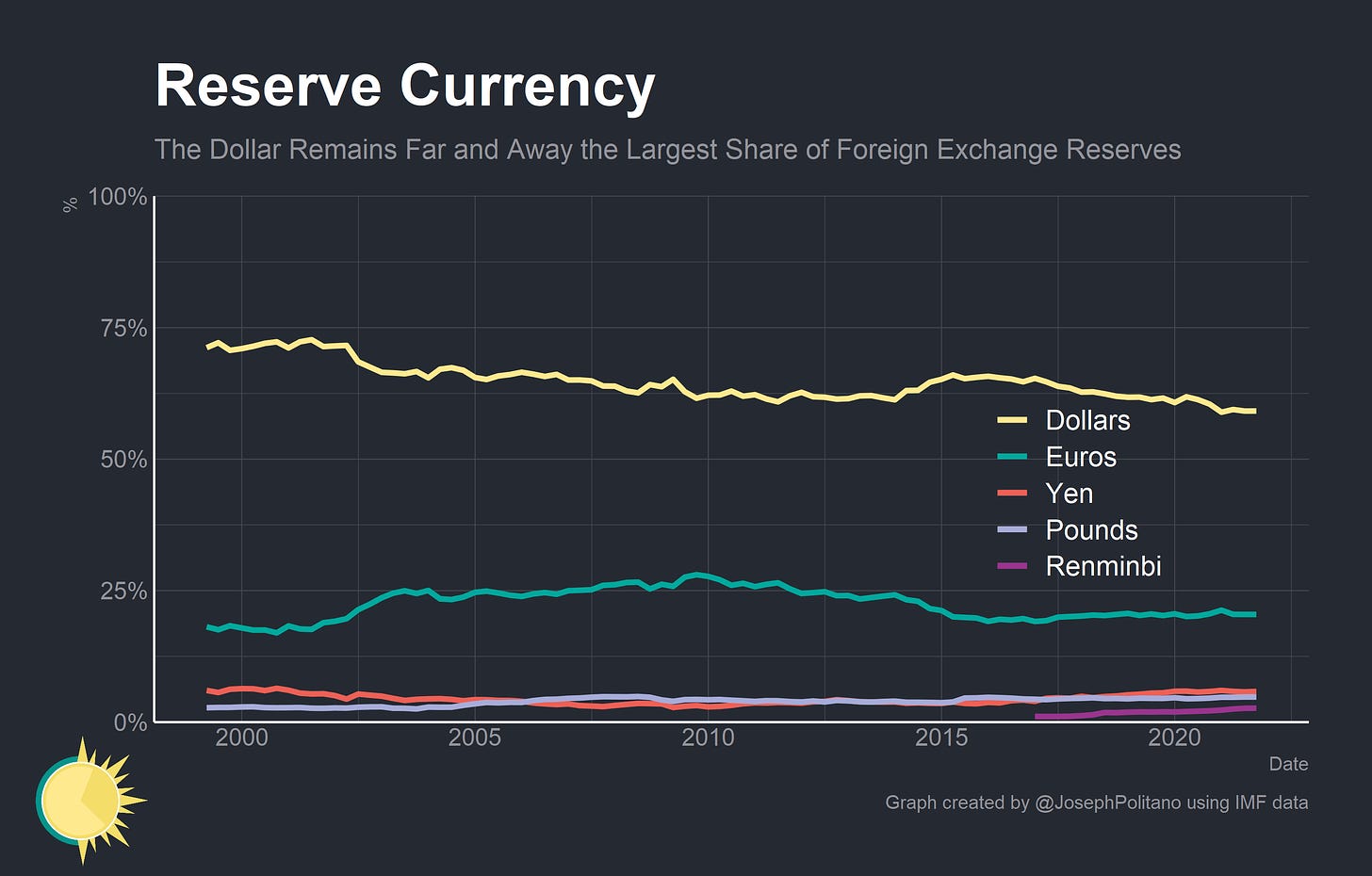

Yet all of this worry belies a critical truth: the US Dollar’s position as global reserve currency is so strong as to be nearly unassailable. No other country has the proper mixture of deep capital markets, clear rule of law, massive economic size, and technological dynamism. The Chinese Renminbi is a much, much smaller proportion of global trade, foreign currency reserves, or global savings. If America’s idiosyncratic foreign policy is pushing countries away from using its currency, than China’s even-more-idiosyncratic foreign policy should cause countries to think twice before giving up the dollar. Nor are Russia’s stockpiles of gold or China’s ability to buy sanctioned commodities in any way substitutes for the decades of institutional legwork necessary to establish a reserve currency. China, for its part, has made exactly zero indication that it even wants to be a reserve currency issuer—as it comes with great responsibilities that the Chinese Communist Party does not want to bear. The dollar has been through much, much worse than this without losing its reserve currency status—and the implementation of sanctions against Russia will not upend the global monetary system.

The Dollar and Institutional Trust

In general, the arguments that sanctions will end or seriously damage the dollar’s reserve currency status fall into one of two camps. The first camp is what I would call the “institutional trust” argument, and the second camp is what I would call the “commodity money” argument.

To members of the first camp, the decision to implement such harsh sanctions on Russia have wrecked global faith in the US government. If a country as powerful as Russia can be completely cut off from global financial markets near-instantaneously, then other autocratic regimes or countries opposed to the US will start thinking about how to wean themselves off their dependence on the dollar for fear of meeting the same fate. The deployment of sanctions against Russia drops these foreign government’s institutional trust in the US, potentially chipping away or upending the dollar-centric financial regime.

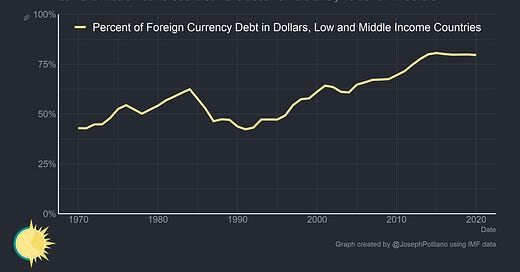

To that I would say a few things. First, the US has deployed its financial and economic power dozens of times in the last few decades in order to achieve geopolitical aims—many times with flimsier justifications than the current sanctions on Russia. None of these sanctions regimes caused lasting damage to the use of the US Dollar abroad. The US has imposed aggressive sanctions on Syria, North Korea, and even China without causing flight from the dollar. In fact, low and middle income countries have actually increased their relative dependence on the US Dollar over the last 20 years.

The sanctions regime against Russia is also much more globally unified than US sanctions against Iran or Venezuela—almost all other major democratic countries have signed on to some level of sanctions against Russia for their invasion of Ukraine. And fundamentally, if the bar for getting kicked out of the global financial system is “don’t start aggressive wars of conquest” then the vast majority of countries—dictatorship or democracy—will have no problems avoiding that fate.

The other major point against the “institutional trust” argument is that there is no viable alternative to the US Dollar. The next three largest currencies as a share of total foreign exchange reserves are the Euro, Japanese Yen, and British Pound Sterling—all of which belong to countries that also share the US’s commitments to the promotion of global democracy and have signed on to sanctions against Russia. For countries worried about the use of financial clout to achieve geopolitical aims China provides no solace—is is even less scrupulous about pursuing idiosyncratic geopolitical aims through economic power. China deployed extensive sanctions against Lithuania after they allowed Taiwan to open a diplomatic office in the country and sanctioned Australia after their government requested an independent inquiry into the origins of COVID-19. That’s hardly the behavior of an impartial administrator of global trade and finance. On the margins I am sure that countries who butt heads with America are thinking more about how to convert their dollar financial claims into real domestic assets and production capabilities, but that is a far cry from attempting to exit or reshape the dollar-lead global financial system entirely.

The Dollar and the Global Commodity System

Zoltan Poszar is a proponent of what I would call the “commodity money” argument. America and its allies are massive consumers of commodities and Russia is a massive producer, so by cutting Russia off from the global dollar financial system America has essentially sunk the price of Russian commodities (as outside of energy they can no longer be exported) and driven up the price of non-Russian commodities (as the supply of commodities outside Russia has declined). Since commodities are the foundation of economic production, the US has essentially caused self-inflicted damage to its own economy. Russia could use its commodity wealth—and its vast gold reserves—to support the value of its currency, possibly even choosing to bring the ruble back to the gold standard. This also leaves the door wide open for China to buy Russian commodities on the cheap and deploy them alongside Chinese commodities in order to start a new global currency regime with a commodity-backed Renminbi at the top.

There are several problems with this theory, but lets start with Russia’s gold. Russia has more than 2000 tons—about $140 billion worth—of gold at its central bank. The country has been accumulating gold reserves for practically just today’s purpose: as a last resort to defend the value of the ruble in the face of disaster. Yet in the country’s moment of need gold is letting them down. For one, global gold markets are simply not deep enough to be able to absorb all of Russia’s gold. Total central bank gold sales have never exceeded 400 tons in a year, and there is no way that Russia would be able to sell more than a small fraction of its gold reserves immediately without crashing global prices. Nevermind that the London Bullion Market Association has already effectively banned Russian gold. Zoltan believes that Russia may not have to sell the gold, simply to post is as collateral and borrow dollars against it, but the obvious question is “borrow from whom?” Russia’s central bank has already been banned from transacting with the vast majority of central banks and financial institutions—that’s the core of their problem—and having gold in a vault in somewhere in Russia does little to change that. The easier solution is to simply continue selling natural gas and oil in exchange for hard currency—a process explicitly carved out of the sanctions because of western Europe’s dependence on Russian energy exports. This can be supplemented through transactions involving a daisy chain of intermediaries that can allow the Russian government to effectively direct some domestic dollar assets and pass off some of the central bank’s reserves.

On the idea for China rescuing Russia and creating a commodity-backed monetary system, there are even more problems. For one, it is not immediately obvious that China would want to swoop in to support Russia in the current situation. The US, EU, and other countries that imposed sanctions are far more important to China’s economy than Russia, and supporting Russia could push these countries to sanction China as well. Indeed, major Chinese state owned banks are already stopped issuing dollar-denominated credit to purchase Russian exports. If the goal is to lend dollars to Russia in exchange for commodities, then China is essentially shouldering a lot of financial risk on Russia’s behalf. Nor will it be immediately easy to do bilateral trade in renminbi and rubles—before the war 88% of Russian exports to China were priced in dollars or euros.

For two, commodity backed money has plenty of problems—there’s a reason why no major country uses the gold standard anymore. By locking the value of your currency to the value of a particular rock, you hamstring the central banks’ ability to use monetary policy to support economic growth or combat inflation. Bad monetary policy under the gold standard lead to the Great Depression, and commodity backed monetary systems were prone to financial crashes. In Russia’s case, going to the gold standard would not really address any problems—the inflation likely to occur in Russia will mostly be due to a sharp decline in real economic output thanks to the war and being cut off from critical imports. This is not a situation like Argentina where the value of the currency is declining rapidly due to monetary mismanagement. A ruble backed by gold will still not be usable for much of international trade and finance until sanctions are ended.

The idea that China would implement some kind of commodity-backed monetary system is also unbelievable. China may be a major producer of many commodities, but it is also a major importer of commodities like oil, gold, and iron. The Chinese Communist Party is not going to end decades of careful micromanagement of its monetary and financial system by basing the value of its currencies on a basket of commodities it cannot even control—nevermind the negative consequences of commodity money even when you do control the basket of commodities. As for becoming a reserve currency, the renminbi still makes up a tiny fraction of international payments as measured by SWIFT—its share is smaller than the Australian or Canadian dollar—so there is a long way to go. More than that, there is barely any evidence that China even desires to make the renminbi the world’s reserve currency, as doing so comes with just as many headaches as benefits.

Making a Reserve Currency

At a very fundamental level, in order to become a reserve currency issuer a government has to be willing to export trillions of dollars in “safe assets” such as cash or government bonds for use by people outside the country. Foreign banks need assets to back up their reserve-currency deposits, and consumers at home and abroad need to be able to have reserve-currency deposits to transact in easily. The reserve currency issuer needs deep financial markets with clear rule of law for foreign governments and corporations to transact and borrow in. Finally, the country needs to manage the risks caused by less regulated foreign markets.

For these reasons China has little to no desire to become the world’s reserve currency issuer—and likely couldn’t do so if it tried. Let’s start with the safe asset exports: China has strict capital controls on consumers, banks, and nonfinancial companies in order to support its export-led growth model and increase government control and surveillance. With these capital controls in place, it is basically impossible for foreigners to save or transact predominantly in renminbi. The capital controls would have to end before China could become the world’s reserve currency, which would entail a radical change in domestic politics (away from surveillance and control) alongside a radical change in foreign politics (away from the export led growth model). These two systems have underpinned decades of relative stability and growth for the Chinese Communist Party, so they have little desire to radically reform them.

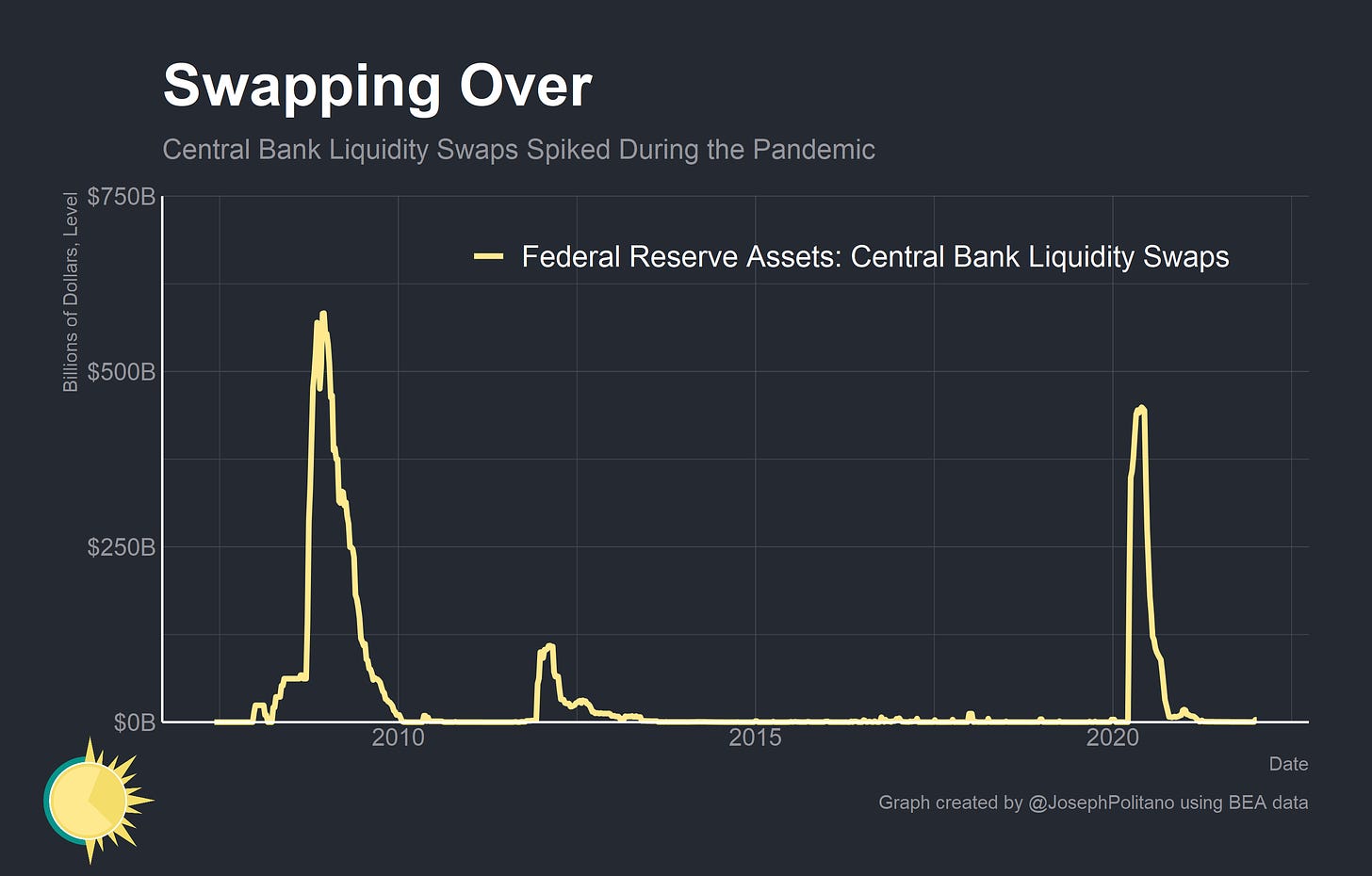

China would also extremely unwilling to manage or backstop a less-regulated foreign financial system than the US. Domestic Chinese financial systems are tightly controlled by the state in order to prevent crisis and achieve macroeconomic goals. State owned banks distribute credit to favored industries and help the country manage its exchange rate while state-backed funds buy equities in order to prevent stock market crashes. The idea that China would allow a recreation of the Eurodollar market (the less-regulated foreign market for dollar banking that remains critical to the dollar’s reserve currency status) is nearly unthinkable. It is even more unthinkable that China would backstop such a market in the way the US has: during the 2008 and 2020 financial crisis the Federal Reserve offered billions of dollars to foreign central banks as liquidity swaps to keep foreign dollar markets working and has since made the Foreign and International Monetary Authorities (FIMA) Repo Facility permanent. The great power of reserve currency status comes with great responsibility, and China is not willing to take on that responsibility.

Even if it was willing, China would likely not be able to make the Renminbi a reserve currency. Chinese financial markets are not deep and liquid enough to sustain the necessary level of borrowing by foreign companies and governments. Trust in fair provision of the rule of law is exceedingly low—not six months ago there were serious worries that the massive, struggling Chinese property developer Evergrande would prioritize repaying domestic creditors over foreign creditors. Opaque currency management makes Chinese monetary policy extremely difficult to predict. Plus, as mentioned earlier, China has also proved extremely willing to use its economic might to achieve geopolitical aims. That’s not a recipe for overtaking the US anytime soon.

Conclusions

The internet runs on negative news—and the financial world is no exception. “The US dollar will likely continue its 70 year reign as global reserve currency” doesn’t get clicks or sell papers, and so it doesn’t get written or shared. But that doesn’t make it any less true.

The 2008 and 2020 recessions were both much tougher challenges for the existing dollar-lead global financial system, and after each crisis the dollar emerged as an even more sought-after asset than before. The history of the British Pound Sterling is instructive here: it took two world wars for America to become the world’s reserve currency issuer, long after it had surpassed the UK in economic output and geopolitical importance. It will take more than sanctions to end the dollar’s hegemony.

This does not mean sanctions are completely without cost. Besides the obvious jump in commodities prices and decline in global output, the continued use of sanctions does eat away at the margins of a unified financial system. A recent working paper from economists at the IMF shows that central bank reserve managers are actively diversifying their holdings away from traditional major currencies (though only about 1/4 of that diversification is into renminbi).

That’s partially because the proliferation of sanctions has occurred with relatively little global coordination. In the same way that we have military rules of engagement, we need financial rules of engagement. That means clear operating procedures for when and how to deploy sanctions, clear criteria for when behavior merits sanctions, and clear off-ramps for de-escalation so that sanctions can end if certain conditions are met. The Russian invasion of Ukraine presents a rare moment when many countries at the center of the global financial system are unified, making it a prime opportunity to codify many of these rules. If they do so, the global dollar financial system will emerge from this crisis even stronger.

Useful article on sanctions and their ramifications on givers and takers and neutral s in between.

Very convincing and clear position on a captivating but not so easy to catch topic (at least for an amateur). I read this blog for the first time, following a link in Adam Tooze’s Chartbook, and I think I will come back for other posts !

Beyond the big question of the statute of reserve currency change, could be a realistic pathway that the Sino Russian trade moves from the “88% of Russian exports to China [were] priced in dollars or euros” to trade flows mainly on an renminbi basis, especially as they are relatively complementary trade flows (commodities vs. manufactured products) ? Eventually, could an Eurasian trade area outside Dollar/Euro influence develop in such a way (the economic reflection of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation) with some level of isolation from the global system ?

Of course, it would to some extent epitomize and foster a vassalization of Russia to China, but could it be a first realistic step (well ahead of shaking the dollar leadership) ?